Heal Your Stressed Brain

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Rochelle Walsh, therapist, explains the problem and how to fix it:

Not all brain damage is from the outside

Long-term stress and burnout cause brain damage; it’s not just a mindset issue—it impacts the brain physiologically. To compound matters, it also increases the risk of neurodegenerative diseases. While the brain can indeed grow new neurons and regenerate itself, chronic stress damages specific regions, and inhibits that.

There are some effects of chronic stress that can seem positive—the amygdalae and hypothalamus are seen to grow larger and stronger, for instance—but this is, unfortunately, “all the better to stress you with”. In compensation for this, chronic stress deprioritizes the pre-frontal cortex and hippocampi, so there goes your reasoning and memory.

This often results in people not managing chronic stress well. Just like a weak heart and lungs might impede the exercise that could make them stronger, the stressed brain is not good at permitting you to do the things that would heal it—preferring to keep you on edge all day, worrying and twitchy, mind racing and body tense. It also tends to lead to autoimmune diseases, due to the increased inflammation (because the body’s threat-detection system as at “jumping at own shadow” levels so it’s deploying every defense it has, including completely inappropriate ones).

Notwithstanding the “Heal Your Stressed Brain” thumbnail, she doesn’t actually go into this in detail and bids us sign up for her masterclass. We at 10almonds however like to deliver, so you can find useful advice and free resources in our links-drop at the bottom of this article.

Meanwhile, if you’d like to hear more about the neurological woes described above, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Meditation That You’ll Actually Enjoy

- How To Manage/Reduce Chronic Stress

- Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

- How Healthy People Regulate Their Emotions

- Sleep: Yes, You Really Do Still Need It!

- Give Your Adrenal Glands A Chance

- The Stress Prescription (Against Aging!)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Actually Causes High Cholesterol?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In 1968, the American Heart Association advised limiting egg consumption to three per week due to cholesterol concerns linked to cardiovascular disease. Which was reasonable based on the evidence available back then, but it didn’t stand the test of time.

Eggs are indeed high in cholesterol, but that doesn’t mean that those who eat them will also be high in cholesterol, because…

It’s not quite what many people think

Some quite dietary pointers to start with:

- Egg yolks are high in cholesterol but have a minimal impact on blood cholesterol.

- Saturated and trans fats (as found in fatty meats or dairy, and some processed foods) have a greater influence on LDL levels than dietary cholesterol.

And on the other hand:

- Unsaturated fats (e.g. from fish, nuts, seeds) have anti-inflammatory benefits

- Fiber-rich foods help lower LDL by affecting fat absorption in the digestive tract

A quick primer on LDL and other kinds of cholesterol:

- VLDL (Very Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- delivers triglycerides and cholesterol to muscle and fat cells for energy

- is converted into LDL after delivery

- LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- is called “bad cholesterol”, which we call that due to its role in arterial plaque formation

- in excess leads to inflammation, overworked macrophage activity, and artery narrowing

- HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein):

- known as “good cholesterol,” picks up excess LDL and returns it to the liver for excretion

- is anti-inflammatory, in addition to regulating LDL levels

There are other factors too, for example:

- Smoking and drinking increase LDL buildup and cause oxidative damage to lipids in general and the blood vessels through which they travel

- Regular exercise, meanwhile, can lower LDL and raise HDL

- Statins and other medications can help lower LDL and manage cholesterol when lifestyle changes and genetics require additional support—but they often come with serious side effects, and the usefulness varies from person to person.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Less Common Oral Hygiene Options

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Less Common Alternatives For Oral Hygiene!

You almost certainly brush your teeth. You might use mouthwash. A lot of people floss for three weeks at a time, often in January.

There are a lot of options for oral hygiene; variations of the above, and many alternatives too. This is a big topic, so rather than try to squeeze it all in one, this will be a several-part series.

- The first part was: Toothpastes & Mouthwashes: Which Help And Which Harm?

- The second part was: Flossing, Better (And Easier!)

- The third (and for now at least, final) part will look at some less common alternatives.

Tooth soap

The idea here is simplicity, and brushing with as few ingredients as possible. Soap cleans your teeth the same way it cleans your (sometimes compositionally quite similar—enamel and all) dishes, without damaging them.

We’d love to link to some science here, but alas, it appears to have not yet been done—at least, we couldn’t find any!

You can make your own tooth soap if you are feeling confident, or you might prefer to buy one ready-made (here’s an example product on Amazon, with various flavor options)

Oil pulling

We are getting gradually more scientific now; there is science for this one… But the (scientific) reviews are mixed:

Wooley et al., 2020, conducted a review of extant studies, and concluded:

❝The limited evidence suggests that oil pulling with coconut oil may have a beneficial effect on improving oral health and dental hygiene❞

The “Science-Based Medicine” project was less positive in its assessment, and declared that all and any studies that found oil pulling to be effective were a matter of researcher/publication bias. We would note that SBM is a private project and is not without its own biases, but for balance, here is what they had to offer:

A more rounded view seems to be that it is a good method for cleaning your teeth if you don’t have better options available (whereby, “better options” is “almost any other method”).

One final consideration, which the above seemed not to consider, is:

If you have sensitive teeth/gums, oil-pulling is the gentlest way of cleaning them, and getting them back into sufficient order that you can comfortably use other methods.

Want to try it? You can use any food-grade oil (coconut oil or olive oil are common choices).

Chewing stick

Not just any stick—a twig of the Salvadora persica tree. This time, there’s lots of science for it, and it’s uncontroversially effective:

❝A number of scientific studies have demonstrated that the miswak (Salvadora persica) possesses antibacterial, anti-fungal, anti-viral, anti-cariogenic, and anti-plaque properties.

Several studies have also claimed that miswak has anti-oxidant, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects. The use of a miswak has an immediate effect on the composition of saliva.

Several clinical studies have confirmed that the mechanical and chemical cleansing efficacy of miswak chewing sticks are equal and at times greater than that of the toothbrush❞

Read in full: A review of the therapeutic effects of using miswak (Salvadora Persica) on oral health

And about the efficacy vs using a toothbrush, here’s an example:

Comparative effect of chewing sticks and toothbrushing on plaque removal and gingival health

Want to try the miswak stick? Here’s an example product on Amazon.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Increase Your Muscle Mass Boost By 26% (No Extra Effort, No Supplements)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You’ve probably seen this technology advertised, but the trick is in how it’s used (which is not how most people use it).

It’s about neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), also called electrical muscle stimulation (EMS); in other words, those squid-like electrode kits that promise “six-pack abs without exercise”, by stimulating the muscles for you—using the exact same tech as for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), for pain relief.

Do they work for pain relief? Yes, for many people in any case. But that’s beyond the scope of today’s article.

Do they work for building muscles as advertised? No. The limiting factor is that they can’t fully exert the muscles in the same way actual exercise can, because of the limitations to how much electrical current can safely be applied.

However…

The cyborgization of your regular workout

A meta-analysis of 13 studies compared two [meta-]groups of exercisers:

- Group 1 doing conventional resistance training

- Group 2 doing the same resistance training, plus NMES at the same time (specifically: NMES of the same muscles being used in the workout)

The analysis had two output variables: strength and muscle mass

What they found: group 2 enjoyed more than 31% greater strength gains, and 26% greater muscle mass gains, from the same training over the same period of time.

Of course, one of the biggest challenges to strength gain and muscle mass gain is hitting a plateau, so it’s worth noting that when they looked at training periods ranging from 2 weeks to 16 weeks, longer durations yielded better results—it is, it seems, the gift that keeps on giving.

You can find the paper here (which also explains how they analysed data from 13 different studies to get one coherent set of results):

How it works and why it matters

While the paper itself does not go into how it works, a reasonable hypothesis is that it works by “confusing” the muscles—because they are receiving mixed signals (one set from your brain, one set from the electrodes), with fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers both working at the same time.

Another way to “confuse” the muscles is by High Intensity [Interval] Resistance Training (HIRT)—which is basically High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), but for resistance training specifically.

See: How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body) and HIIT, But Make It HIRT

Now, we want to confuse our muscles, not our readers, so if that’s all too much to juggle at once, just pick one and go with it. But today’s article is about the RT+NEMS combination, so perhaps you’ll pick that.

Why it matters: as we get older, sarcopenia (the loss of muscle mass) becomes more of an issue, and even if we’re not inclined to a career in bodybuilding, we do still need to at least maintain a healthy muscle mass because:

- Strong muscles improve our stability and make us less likely to fall

- Strong muscles force the body to build strong bones to hold them on, which means lower risk of fractures or worse

- Muscle mass itself improves the body’s basal metabolic rate, which means systemic benefits to the whole body (including against metabolic diseases especially)

See also: Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Want to try it?

If you don’t already have a NMES/EMS/TENS kit lying around the house, here’s an example product on Amazon—remember to use it simultaneously with your regular resistance training workout, on the same muscles at the same time, to get the benefit we talked about! 😎

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

From Painkillers To Hunger-Killers

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Here’s this week’s selection of health news discoveries, the science behind them, what they mean for you, and where you can go from there:

Killing more than pain

It’s well-known that overuse of opioids can lead to many problems, and here’s another one: messing with the endocrine system. This time, mostly well-evidenced in men—however, the researchers are keen to point out that absence of evidence is very much not evidence of absence, hence “the hidden effects” in the headline below. It’s not that the effects are hard to see—it’s that a lot of the research has yet to be done. For now, though, we know at the very least that there’s an association between opioid use and hyperprolactinemia in men. The same research also begins to shine a light on the effects of opioid use on the hypothalamic-pituitary system and bone health, too:

Read in full: The hidden effects of opioid use on the endocrine system

Related: The 7 Approaches To Pain Management

Gut microbiome dysbiosis may lead to slipping disks

These things sound quite unconnected, but the association is strong. The likely mechanism of action is that the gut dysbiosis influences systemic inflammation, and thus spinal health—because the gut-spine axis cannot really be disconnected (while you’re alive, at least). It’s especially likely if you’re over 50 and female:

Read in full: Are back problems influenced by your gut?

Related: Is Your Gut Leading You Into Osteoporosis?

The Internet is really really great (for brains)

It’s common to see many articles on the Internet telling us, paradoxically, that we should spend less time on the Internet. However… Remember when in the 90s, it was all about “the information superhighway”? It turns out, the fact that it’s more like “the information spaghetti junction” these days doesn’t change the fact that stimulation is good for our brains, and daily Internet use improves memory, because of the different way that we index and store information that came from a virtual source. While there are parts of your brain for “things at home” and “things at the local supermarket”, there are also parts for “things at 10almonds” and “things at Facebook” and so forth. You are, in effect, building a vast mental library as you surf:

Read in full: Daily internet use supercharges your memory!

Related: Make Social Media Work For Your Mental Health

Fall back

Around this time of year in many places in the Northern Hemisphere, the clocks go back an hour (it’s next weekend in the US and Canada, by the way, and this weekend in most of Europe). Many enjoy this as the potential for an extra hour’s sleep, but for night owls, it can be more of a nuisance than a benefit—throwing out what’s often an already difficult relationship with the clock, and presenting challenges both practical and physiological (different processing of melatonin, for instance). Here be science:

Read in full: Why night owls struggle more when the clocks go back

Related: Early Bird Or Night Owl? Genes vs Environment

Can you outrun your hunger?

It seems so, though benefits are strongest in women. We say “outrun”, though this study did use stationary cycling. To put it in few words, intense exercise (but not moderate exercise) significantly reduced acylated ghrelin (hunger hormone) levels, and subjective reports of hunger, especially in women:

Read in full: Study finds intense exercise may suppress appetite in healthy humans

Related: 3 Appetite Suppressants Better Than Ozempic

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Couple’s Guide to Thriving with ADHD – by Melissa Orlov and Nancie Kohlenberger

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

ADHD (what a misleadingly-named condition) is most often undiagnosed in adults, especially older adults, and has far-reaching effects. This book explores those!

Oftentimes ADHD is not a deficit of attention, it’s just a lack of choice about where one’s attention goes. And the H? It’s mostly not what people think it is. The diagnostic criteria have moved far beyond the original name.

But in a marriage, ADHD symptoms such as wandering attention, forgetfulness, impulsiveness, and a focus on the “now” to the point of losing sight of the big picture (the forgotten past and the unplanned future), can cause conflict.

The authors write in a way that is intended for the ADHD and/or non-ADHD partner to read, and ideally, for both to read.

They shine light on why people with or without ADHD tend towards (or away from) certain behaviours, what miscommunications can arise, and how to smooth them over.

Best of all, an integrated plan for getting you both on the same page, so that you can tackle anything that arises, as the diverse team (with quite different individual strengths) that you are.

Bottom line: if you or a loved one has ADHD symptoms, this book can help you navigate and untangle what can otherwise sometimes get a little messy.

Click here to check out The Couple’s Guide to Thriving with ADHD, and learn how to do just that!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What happens in my brain when I get a migraine? And what medications can I use to treat it?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Migraine is many things, but one thing it’s not is “just a headache”.

“Migraine” comes from the Greek word “hemicrania”, referring to the common experience of migraine being predominantly one-sided.

Some people experience an “aura” preceding the headache phase – usually a visual or sensory experience that evolves over five to 60 minutes. Auras can also involve other domains such as language, smell and limb function.

Migraine is a disease with a huge personal and societal impact. Most people cannot function at their usual level during a migraine, and anticipation of the next attack can affect productivity, relationships and a person’s mental health.

Francisco Gonzelez/Unsplash What’s happening in my brain?

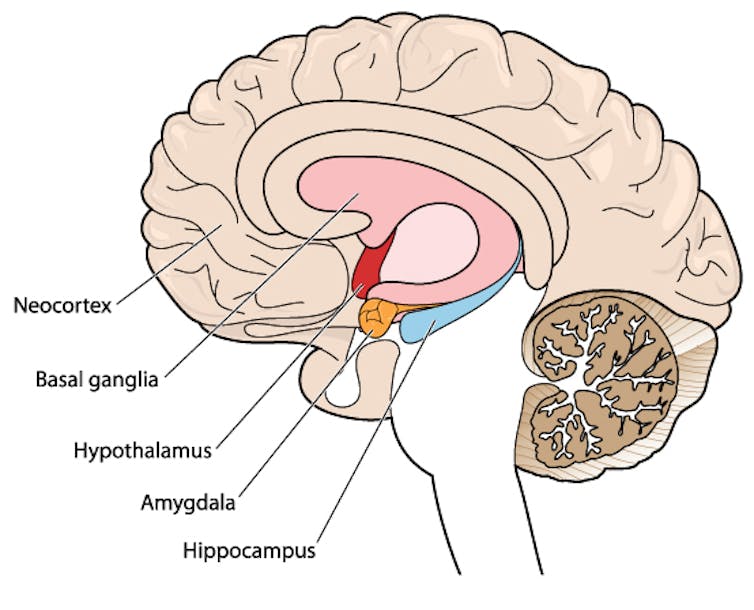

The biological basis of migraine is complex, and varies according to the phase of the migraine. Put simply:

The earliest phase is called the prodrome. This is associated with activation of a part of the brain called the hypothalamus which is thought to contribute to many symptoms such as nausea, changes in appetite and blurred vision.

The hypothalamus is shown here in red. Blamb/Shutterstock Next is the aura phase, when a wave of neurochemical changes occur across the surface of the brain (the cortex) at a rate of 3–4 millimetres per minute. This explains how usually a person’s aura progresses over time. People often experience sensory disturbances such as flashes of light or tingling in their face or hands.

In the headache phase, the trigeminal nerve system is activated. This gives sensation to one side of the face, head and upper neck, leading to release of proteins such as CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide). This causes inflammation and dilation of blood vessels, which is the basis for the severe throbbing pain associated with the headache.

Finally, the postdromal phase occurs after the headache resolves and commonly involves changes in mood and energy.

What can you do about the acute attack?

A useful way to conceive of migraine treatment is to compare putting out campfires with bushfires. Medications are much more successful when applied at the earliest opportunity (the campfire). When the attack is fully evolved (into a bushfire), medications have a much more modest effect.

Aspirin

For people with mild migraine, non-specific anti-inflammatory medications such as high-dose aspirin, or standard dose non-steroidal medications (NSAIDS) can be very helpful. Their effectiveness is often enhanced with the use of an anti-nausea medication.

Triptans

For moderate to severe attacks, the mainstay of treatment is a class of medications called “triptans”. These act by reducing blood vessel dilation and reducing the release of inflammatory chemicals.

Triptans vary by their route of administration (tablets, wafers, injections, nasal sprays) and by their time to onset and duration of action.

The choice of a triptan depends on many factors including whether nausea and vomiting is prominent (consider a dissolving wafer or an injection) or patient tolerability (consider choosing one with a slower onset and offset of action).

As triptans constrict blood vessels, they should be used with caution (or not used) in patients with known heart disease or previous stroke.

Triptans should be used cautiously in patients with heart disease. CDC/Unsplash Gepants

Some medications that block or modulate the release of CGRP, which are used for migraine prevention (which we’ll discuss in more detail below), also have evidence of benefit in treating the acute attack. This class of medication is known as the “gepants”.

Gepants come in the form of injectable proteins (monoclonal antibodies, used for migraine prevention) or as oral medication (for example, rimegepant) for the acute attack when a person has not responded adequately to previous trials of several triptans or is intolerant of them.

They do not cause blood vessel constriction and can be used in patients with heart disease or previous stroke.

Ditans

Another class of medication, the “ditans” (for example, lasmiditan) have been approved overseas for the acute treatment of migraine. Ditans work through changing a form of serotonin receptor involved in the brain chemical changes associated with the acute attack.

However, neither the gepants nor the ditans are available through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for the acute attack, so users must pay out-of-pocket, at a cost of approximately A$300 for eight wafers.

What about preventing migraines?

The first step is to see if lifestyle changes can reduce migraine frequency. This can include improving sleep habits, routine meal schedules, regular exercise, limiting caffeine intake and avoiding triggers such as stress or alcohol.

Despite these efforts, many people continue to have frequent migraines that can’t be managed by acute therapies alone. The choice of when to start preventive treatment varies for each person and how inclined they are to taking regular medication. Those who suffer disabling symptoms or experience more than a few migraines a month benefit the most from starting preventives.

Some people will take medicines to prevent migraines. Tbel Abuseridze/Unsplash Almost all migraine preventives have existing roles in treating other medical conditions, and the physician would commonly recommend drugs that can also help manage any pre-existing conditions. First-line preventives include:

- tablets that lower blood pressure (candesartan, metoprolol, propranolol)

- antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine)

- anticonvulsants (sodium valproate, topiramate).

Some people have none of these other conditions and can safely start medications for migraine prophylaxis alone.

For all migraine preventives, a key principle is starting at a low dose and increasing gradually. This approach makes them more tolerable and it’s often several weeks or months until an effective dose (usually 2- to 3-times the starting dose) is reached.

It is rare for noticeable benefits to be seen immediately, but with time these drugs typically reduce migraine frequency by 50% or more.

‘Nothing works for me!’

In people who didn’t see any effect of (or couldn’t tolerate) first-line preventives, new medications have been available on the PBS since 2020. These medications block the action of CGRP.

The most common PBS-listed anti-CGRP medications are injectable proteins called monoclonal antibodies (for example, galcanezumab and fremanezumab), and are self-administered by monthly injections.

These drugs have quickly become a game-changer for those with intractable migraines. The convenience of these injectables contrast with botulinum toxin injections (also effective and PBS-listed for chronic migraine) which must be administered by a trained specialist.

Up to half of adolescents and one-third of young adults are needle-phobic. If this includes you, tablet-form CGRP antagonists for migraine prevention are hopefully not far away.

Data over the past five years suggest anti-CGRP medications are safe, effective and at least as well tolerated as traditional preventives.

Nonetheless, these are used only after a number of cheaper and more readily available first-line treatments (all which have decades of safety data) have failed, and this also a criterion for their use under the PBS.

Mark Slee, Associate Professor, Clinical Academic Neurologist, Flinders University and Anthony Khoo, Lecturer, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: