Hazelnuts vs Cashews – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing hazelnuts to cashews, we picked the hazelnuts.

Why?

It’s close! This one’s interesting…

In terms of macros, hazelnuts have more fiber and fats, while cashews have more protein and carbs. All in all, all good stuff all around; maybe a win for one or the other depending on your priorities. We’d pick hazelnuts here, but your preference may vary.

When it comes to vitamins, hazelnuts have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, and E, while cashews have more vitamin K. An easy win for hazelnuts here, and the margins weren’t close.

In the category of minerals, hazelnuts have more calcium, manganese, and potassium, while cashews have more copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc. This is a win for cashews, but it’s worth noting that cup for cup, both of these nuts provide more than the daily requirement of most of those minerals. This means that in practical terms, it doesn’t matter too much that (for example), while cashews provide 732% of the daily requirement for copper, hazelnuts “only” provide 575%. So while this category remains a victory for cashews, it’s something of a “on paper” thing for the most part.

Adding up the sections (ambivalent + clear win for hazelnuts + nominal win for cashews) means that in total today we’re calling it in favour of hazelnuts… But as ever, enjoy both, because both are good and so is diversity!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Build Muscle (Healthily!)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Do You Have To Gain?

We have previously promised a three-part series about changing one’s weight:

- Losing weight (specifically, losing fat)

- Gaining weight (specifically, gaining muscle)

- Gaining weight (specifically, gaining fat)

And yes, that last one is also something that some people want/need to do (healthily!), and want/need help with that.

There will be, however, no need for a “losing muscle” article, because (even though sometimes a person might have some reason to want to do this), it’s really just a case of “those things we said for gaining muscle? Don’t do those and the muscle will atrophy naturally”.

Here’s the first part: How To Lose Weight (Healthily!)

While some people will want to lose fat, please do be aware that the association between weight loss and good health is not nearly so strong as the weight loss industry would have you believe:

And, while BMI is not a useful measure of health in general, it’s worth noting that over the age of 65, a BMI of 27 (which is in the high end of “overweight”, without being obese) is associated with the lowest all-cause mortality:

BMI and all-cause mortality in older adults: a meta-analysis

Body weight, muscle mass, and protein:

That BMI of 27, or whatever weight you might wish to be, ignores body composition. You’re probably aware that volume-for-volume, muscle weighs more than fat.

You’re also probably aware that if we’re not careful, we tend to lose muscle as we get older. This is known as age-related sarcopenia:

Protein, & Fighting Sarcopenia

Dr. Gabrielle Lyon, our featured expert in the above article, recommends getting at least 1.6g of protein per kg of body weight per day (Americans, divide your weight in pounds by 2.2 to get your weight in kg).

So for example, if you weigh 165lb, that’s 75kg, that’s 1.6×75=120g of protein per day.

There is an upper limit to how much protein per day is healthy, and that limit is probably around 2g of protein per kg of body weight per day:

Protein: How Much Do We Need, Really?

You may be wondering: should we go for animal or plant protein? In which case, the short version is:

- If you only care about muscle growth, any complete sources of protein are fine

- If you care about your general health too, then avoiding red meat is best, but other common protein sources are all fine

- Unprocessed is (unsurprisingly) better than processed in either case

Longer version: Plant vs Animal Protein: Head to Head

What exercises are best for muscle-building?

Of course, different muscles require different exercises, but for all of them, resistance training is what builds muscle the most, and it’s pretty much impossible to build a lot of muscle otherwise.

Check out: Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Prepare to fail!

No, really, prepare to fail. Because while resistance training in general is good for maintaining strong muscles and bones, you will only gain muscle if your current muscle is not enough to do the exercise:

- If you do a heavy resistance exercise without undue difficulty, your muscles will say to each other “Good job, team! That was hard, but luckily we were strong enough; no changes necessary”.

- If you do a heavy resistance exercise to the point where you can no longer do it (called: training to failure), then your muscles will say to each other “Oof, what a task! What we’ve got here is clearly not enough, so we’ll have to add more muscle for next time”.

Safety note: training to failure comes with safety risks. If using free weights or weight machines, please do so under well-trained supervision. If doing it with bodyweight (e.g. press-ups until you can press no more) or resistance bands, please check with your doctor first to ensure this is safe for you.

You can also increase the effectiveness of your resistance training by doing it in a way that “confuses” your muscles, making it harder for them to adapt in the moment, and thus forcing them to adapt more in the long term (e.g. get bigger and stronger):

HIIT, But Make It HIRT: High Intensity Resistance Training

Make time for recovery

While many kinds of exercise can be done daily, exercise to build muscle(s) means at the very least resting that muscle (or muscle group) the next day.

For this reason, a lot of bodybuilders have for example a week’s schedule that might look like:

- Monday: Upper body training

- Wednesday: Lower body training

- Friday: Core strength training

…and rest on other days. This gives most muscles a full week of recovery, and every muscle at least 48 hours of recovery.

Note: bodybuilders, like children (who are also doing a lot of body-building, in their own way) need more sleep in order to allow for this recovery and growth to occur. Serious bodybuilders often aim for 12 hours sleep per day. This might be impractical, undesirable, or even impossible for some people, but it’s a factor to be borne in mind and not forgotten.

See also:

Overdone It? How To Speed Up Recovery After Exercise (According To Actual Science)

Anything else that can (safely and healthily) be done to promote muscle growth?

There are a lot of supplements on the market; some are healthy and helpful, other not so much. Here are some we’ve written about:

- What To Eat, Take, And Do Before A Workout

- Creatine: Very Different For Young & Old People

- Ginseng: Exercising With Less Soreness!

- Taurine’s Benefits For Heart Health And More

- Topping Up Testosterone? What To Consider

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Treadmill vs Road

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝Why do I get tired much more quickly running outside, than I do on the treadmill? Every time I get worn out quickly but at home I can go for much longer!❞

Short answer: the reason is Newton’s laws of motion.

In other words: on a treadmill, you need only maintain your position in space relative the the Earth while the treadmill moves beneath you, whereas on the road, you need to push against the Earth with sufficient force to move it relative to your body.

Illustrative thought experiment to make that clearer: if you were to stand on a treadmill with roller skates, and hold onto the bar with even just one finger, you would maintain your speed as far as the treadmill’s computer is concerned—whereas to maintain your speed on a flat road, you’d still need to push with your back foot every few yards or so.

More interesting answer: it’s a qualitatively different exercise (i.e. not just quantitively different). This is because of all that pushing you’re having to do on the road, while on a treadmill, the only pushing you have to do is just enough to counteract gravity (i.e. to keep you upright).

As such, both forms of running are a cardio exercise (because simply moving your legs quickly, even without having to apply much force, is still something that requires oxygenated blood feeding the muscles), but road-running adds an extra element of resistance exercise for the muscles of your lower body. Thus, road-running will enable you to build-maintain muscle much more than treadmill-running will.

Some extra things to bear in mind, however:

1) You can increase the resistance work for either form of running, by adding weight (such as by wearing a weight vest):

Weight Vests Against Osteoporosis: Do They Really Build Bone?

…and while road-running will still be the superior form of resistance work (for the reasons we outlined above), adding a weight vest will still be improving your stabilization muscles, just as it would if you were standing still while holding the weight up.

2) Stationary cycling does not have the same physics differences as stationary running. By this we mean: an exercise bike will require your muscles to do just as much pushing as they would on a road. This makes stationary cycling an excellent choice for high intensity resistance training (HIRT):

3) The best form of exercise is the one that you will actually do. Thus, when it’s raining sidewise outside, a treadmill inside will get exercise done better than no running at all. Similarly, a treadmill exercise session takes a lot less preparation (“switch it on”) than a running session outside (“get dressed appropriately for the weather, apply sunscreen if necessary, remember to bring water, etc etc”), and thus is also much more likely to actually occur. The ability to stop whenever one wants is also a reassuring factor that makes one much more likely to start. See for example:

How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Give Us This Day Our Daily Dozen

This is Dr. Michael Greger. He’s a physician-turned-author-educator, and we’ve featured him and his work occasionally over the past year or so:

- Brain Food? The Eyes Have It! ← this is about dark leafy greens, lutein, & avoiding Alzheimer’s

- Twenty-One, No Wait, Twenty Tweaks For Better Health ← he says 21, but we say one of them is very skippable. Check it out and decide what you think!

- Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight ← his top well-evidenced interventions specifically for slowing aging

But what we’ve not covered, astonishingly, is one of the things for which he’s most famous, which is…

Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen

Based on the research in the very information-dense tome that his his magnum opus How Not To Die (while it doesn’t confer immortality, it does help avoid the most common causes of death), Dr. Greger recommends that we take care to enjoy each of the following things per day:

Beans

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: ½ cup cooked beans, ¼ cup hummus

Greens

- Servings: 2 per day

- Examples: 1 cup raw, ½ cup cooked

Cruciferous vegetables

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ½ cup chopped, 1 tablespoon horseradish

Other vegetables

- Servings: 2 per day

- Examples: ½ cup non-leafy vegetables

Whole grains

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: ½ cup hot cereal, 1 slice of bread

Berries

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ½ cup fresh or frozen, ¼ cup dried

Other fruits

- Servings: 3 per day

- Examples: 1 medium fruit, ¼ cup dried fruit

Flaxseed

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: 1 tablespoon ground

Nuts & (other) seeds

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ¼ cup nuts, 2 tablespoons nut butter

Herbs & spices

- Servings: 1 per day

- Examples: ¼ teaspoon turmeric

Hydrating drinks

- Servings: 60 oz per day

- Examples: Water, green tea, hibiscus tea

Exercise

- Servings: Once per day

- Examples: 90 minutes moderate or 40 minutes vigorous

Superficially it seems an interesting choice to, after listing 11 foods and drinks, have the 12th item as exercise but not add a 13th one of sleep—but perhaps he quite reasonably expects that people get a dose of sleep with more consistency than people get a dose of exercise. After all, exercise is mostly optional, whereas if we try to skip sleep for too long, our body will force the matter for us.

Further 10almonds notes:

- We’d consider chia superior to flax, but you do you. Flax is a fine choice also.

- We recommend trying to get each of these top 5 most health-giving spices in daily if you can.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

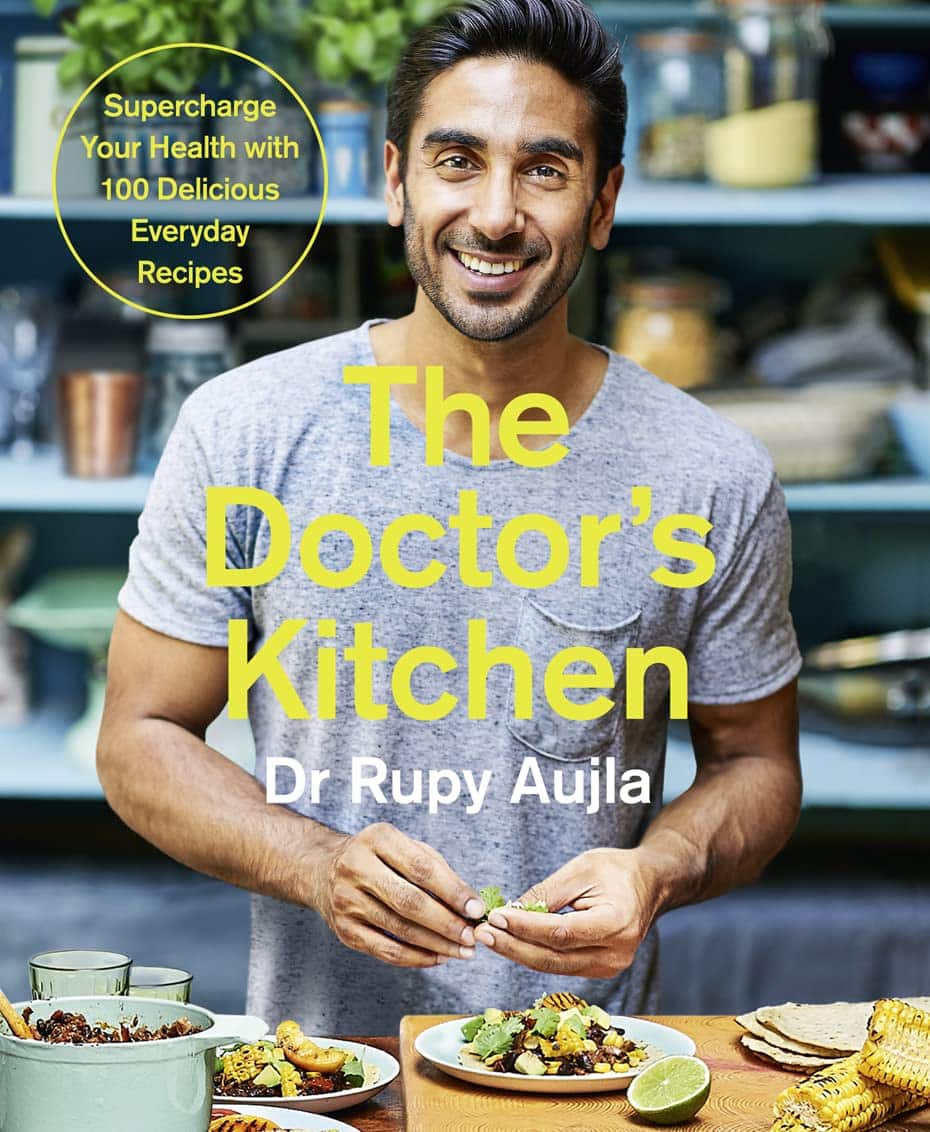

The Doctor’s Kitchen – by Dr. Rupy Aujla

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve featured Dr. Aujla before as an expert-of-the-week, and now it’s time to review a book by him. What’s his deal, and what should you expect?

Dr. Aujla first outlines the case for food as medicine. Not just “eat nutritionally balanced meals”, but literally, “here are the medicinal properties of these plants”. Think of some of the herbs and spices we’ve featured in our Monday Research Reviews, and add in medicinal properties of cancer-fighting cruciferous vegetables, bananas with dopamine and dopamine precursors, berries full of polyphenols, hemp seeds that fight cognitive decline, and so forth.

Most of the book is given over to recipes. They’re plant-centric, but mostly not vegan. They’re consistent with the Mediterranean diet, but mostly Indian. They’re economically mindful (favoring cheap ingredients where reasonable) while giving a nod to where an extra dollar will elevate the meal. They don’t give calorie values etc—this is a feature not a bug, as Dr. Aujla is of the “positive dieting” camp that advocates for us to “count colors, not calories”. Which, we have to admit, makes for very stress-free cooking, too.

Dr. Aujla is himself an Indian Brit, by the way, which gives him two intersecting factors for having a taste for spices. If you don’t share that taste, just go easier on the pepper etc.

As for the medicinal properties we mentioned up top? Four pages of references at the back, for any who are curious to look up the science of them. We at 10almonds do love references!

Bottom line: if you like tasty food and you’re looking for a one-stop, well-rounded, food-as-medicine cookbook, this one is a top-tier choice.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Where Nutrition Meets Habits!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Where Nutrition Meets Habits…

This is Claudia Canu, MSc., INESEM. She’s on a mission to change the way we eat:

Often, diet is a case of…

- Healthy

- Easy

- Cheap

(choose two)

She wants to make it all three, and tasty too. She has her work cut out for her, but she’s already blazed quite a trail personally:

❝Nine months before turning 40 years old, I set a challenge for myself: Arrive to the day I turn 40 as the best possible version of myself, physically, mentally and emotionally.❞

~ Claudia Canu

In Her Own Words: My Journey To My Healthy 40s

And it really was quite a journey:

- September: Changes That Destabilize

- October: Looking for Focus

- November: New Habits

- December: Analyzing The First Results

- January: Traveling & Perfectionism

- February: Habits & Goals

- March: Connection, Cravings, & Organization

- April: Physical & Emotional Changes After 7 Months

- May: Reflections & Considerations

- June: Challenge Is Over

For those of us who’d like the short-cut rather than a nine-month quasi-spiritual journey… based on both her experience, and her academic and professional background in nutrition, her main priorities that she settled on were:

- Making meals actually nutritionally balanced, which meant re-thinking what she thought a meal “should” be

- Making nutritionally balanced meals that didn’t require a lot of skill and/or resources

- That’s it!

But, easier said than done… Where to begin?

She shares an extensive list of recipes, from meals to snacks (I thought I was the only one who made coffee overnight oats!), but the most important thing from her is:

Claudia’s 10 Guiding Principles:

- Buy only fresh ingredients that you are going to cook yourself. If you decide to buy pre-cooked ones, make sure they do not have added ingredients, especially sugar (in all its forms).

- Use easy and simple cooking methods.

- Change ingredients every time you prepare your meals.

- Prepare large quantities for three or four days.

- Store the food separately in tightly closed Tupperware.

- Organize yourself to always have ready-to-eat food in the fridge.

- When hungry, mix the ingredients in the ideal amounts to cover the needs of your body.

- Chew well and take the time to taste your food.

- Eat foods that you like and enjoy.

- Do not overeat but don’t undereat either.

We have only two quibbles with this fine list, which are:

About Ingredients!

Depending on what’s available around you, frozen and/or tinned “one-ingredient” foods can be as nutritional as (if not more nutritional than) fresh ones. By “one-ingredient” foods here we mean that if you buy a frozen pack of chopped onions, the ingredients list will be: “chopped onions”. If you buy a tin of tomatoes, the ingredients will say “Tomatoes” or at most “Tomatoes, Tomato Juice”, for example.

She does list the ingredients she keeps in; the idea that with these in the kitchen, you’ll never be in the position of “oh, we don’t have much in, I guess it’s a pizza delivery night” or “well there are some chicken nuggets at the back of the freezer”.

Check Out And Plan: 10 Types Of Ingredients You Should Always Keep In Your Kitchen

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow?

Preparing large quantities for three or four days can result in food for one or two days if the food is unduly delicious

But! Claudia has a remedy for that:

Read: How To Eliminate Food Cravings And What To Do When They Win

Anyway, there’s a wealth of resources in the above-linked pages, so do check them out!

Perhaps the biggest take-away is to ask yourself:

“What are my guiding principles when it comes to food?”

If you don’t have a ready answer, maybe it’s time to tackle that—whether Claudia’s way or your own!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gut Health and Anxiety

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I’d like to read articles on gut health and anxiety❞

We hope you caught yesterday’s edition of 10almonds, which touched on both of those! Other past editions you might like include:

We’ll be sure to include more going forward, too!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: