Could not getting enough sleep increase your risk of type 2 diabetes?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Not getting enough sleep is a common affliction in the modern age. If you don’t always get as many hours of shut-eye as you’d like, perhaps you were concerned by news of a recent study that found people who sleep less than six hours a night are at higher risk of type 2 diabetes.

So what can we make of these findings? It turns out the relationship between sleep and diabetes is complex.

The study

Researchers analysed data from the UK Biobank, a large biomedical database which serves as a global resource for health and medical research. They looked at information from 247,867 adults, following their health outcomes for more than a decade.

The researchers wanted to understand the associations between sleep duration and type 2 diabetes, and whether a healthy diet reduced the effects of short sleep on diabetes risk.

As part of their involvement in the UK Biobank, participants had been asked roughly how much sleep they get in 24 hours. Seven to eight hours was the average and considered normal sleep. Short sleep duration was broken up into three categories: mild (six hours), moderate (five hours) and extreme (three to four hours). The researchers analysed sleep data alongside information about people’s diets.

Some 3.2% of participants were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during the follow-up period. Although healthy eating habits were associated with a lower overall risk of diabetes, when people ate healthily but slept less than six hours a day, their risk of type 2 diabetes increased compared to people in the normal sleep category.

The researchers found sleep duration of five hours was linked with a 16% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes, while the risk for people who slept three to four hours was 41% higher, compared to people who slept seven to eight hours.

One limitation is the study defined a healthy diet based on the number of servings of fruit, vegetables, red meat and fish a person consumed over a day or a week. In doing so, it didn’t consider how dietary patterns such as time-restricted eating or the Mediterranean diet may modify the risk of diabetes among those who slept less.

Also, information on participants’ sleep quantity and diet was only captured at recruitment and may have changed over the course of the study. The authors acknowledge these limitations.

Why might short sleep increase diabetes risk?

In people with type 2 diabetes, the body becomes resistant to the effects of a hormone called insulin, and slowly loses the capacity to produce enough of it in the pancreas. Insulin is important because it regulates glucose (sugar) in our blood that comes from the food we eat by helping move it to cells throughout the body.

We don’t know the precise reasons why people who sleep less may be at higher risk of type 2 diabetes. But previous research has shown sleep-deprived people often have increased inflammatory markers and free fatty acids in their blood, which impair insulin sensitivity, leading to insulin resistance. This means the body struggles to use insulin properly to regulate blood glucose levels, and therefore increases the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Further, people who don’t sleep enough, as well as people who sleep in irregular patterns (such as shift workers), experience disruptions to their body’s natural rhythm, known as the circadian rhythm.

This can interfere with the release of hormones like cortisol, glucagon and growth hormones. These hormones are released through the day to meet the body’s changing energy needs, and normally keep blood glucose levels nicely balanced. If they’re compromised, this may reduce the body’s ability to handle glucose as the day progresses.

These factors, and others, may contribute to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes seen among people sleeping less than six hours.

While this study primarily focused on people who sleep eight hours or less, it’s possible longer sleepers may also face an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Research has previously shown a U-shaped correlation between sleep duration and type 2 diabetes risk. A review of multiple studies found getting between seven to eight hours of sleep daily was associated with the lowest risk. When people got less than seven hours sleep, or more than eight hours, the risk began to increase.

The reason sleeping longer is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes may be linked to weight gain, which is also correlated with longer sleep. Likewise, people who don’t sleep enough are more likely to be overweight or obese.

Good sleep, healthy diet

Getting enough sleep is an important part of a healthy lifestyle and may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Based on this study and other evidence, it seems that when it comes to diabetes risk, seven to eight hours of sleep may be the sweet spot. However, other factors could influence the relationship between sleep duration and diabetes risk, such as individual differences in sleep quality and lifestyle.

While this study’s findings question whether a healthy diet can mitigate the effects of a lack of sleep on diabetes risk, a wide range of evidence points to the benefits of healthy eating for overall health.

The authors of the study acknowledge it’s not always possible to get enough sleep, and suggest doing high-intensity interval exercise during the day may offset some of the potential effects of short sleep on diabetes risk.

In fact, exercise at any intensity can improve blood glucose levels.

Giuliana Murfet, Casual Academic, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney and ShanShan Lin, Senior Lecturer, School of Public Health, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

I have a stuffy nose, how can I tell if it’s hay fever, COVID or something else?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hay fever (also called allergic rhinitis) affects 24% of Australians. Symptoms include sneezing, a runny nose (which may feel blocked or stuffy) and itchy eyes. People can also experience an itchy nose, throat or ears.

But COVID is still spreading, and other viruses can cause cold-like symptoms. So how do you know which one you’ve got?

Lysenko Andrii/Shutterstock Remind me, how does hay fever cause symptoms?

Hay fever happens when a person has become “sensitised” to an allergen trigger. This means a person’s body is always primed to react to this trigger.

Triggers can include allergens in the air (such as pollen from trees, grasses and flowers), mould spores, animals or house dust mites which mostly live in people’s mattresses and bedding, and feed on shed skin.

When the body is exposed to the trigger, it produces IgE (immunoglobulin E) antibodies. These cause the release of many of the body’s own chemicals, including histamine, which result in hay fever symptoms.

People who have asthma may find their asthma symptoms (cough, wheeze, tight chest or trouble breathing) worsen when exposed to airborne allergens. Spring and sometimes into summer can be the worst time for people with grass, tree or flower allergies.

However, animal and house dust mite symptoms usually happen year-round.

Ryegrass pollen is a common culprit. bangku ceria/Shutterstock What else might be causing my symptoms?

Hay fever does not cause a fever, sore throat, muscle aches and pains, weakness, loss of taste or smell, nor does it cause you to cough up mucus.

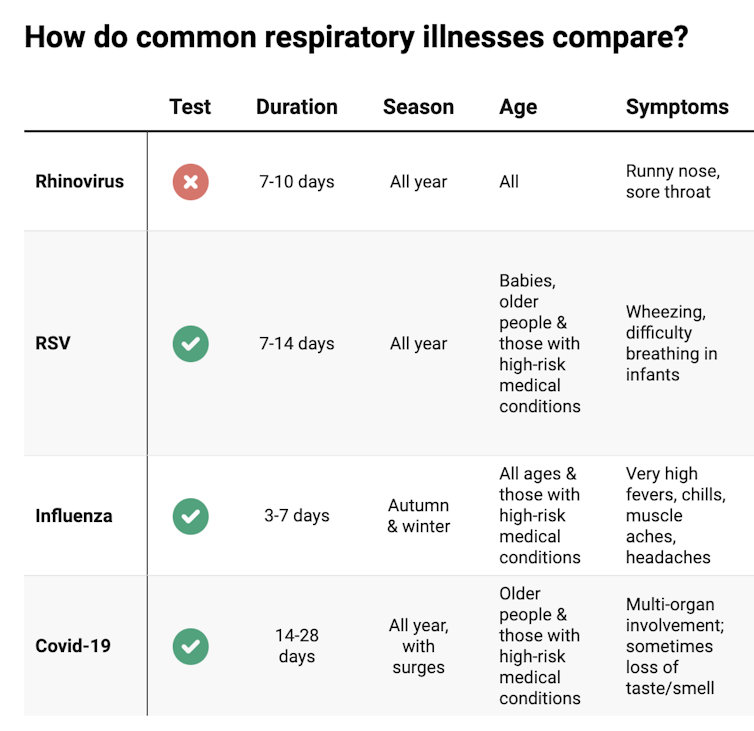

These symptoms are likely to be caused by a virus, such as COVID, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or a “cold” (often caused by rhinoviruses). These conditions can occur all year round, with some overlap of symptoms:

Natasha Yates/The Conversation COVID still surrounds us. RSV and influenza rates appear higher than before the COVID pandemic, but it may be due to more testing.

So if you have a fever, sore throat, muscle aches/pains, weakness, fatigue, or are coughing up mucus, stay home and avoid mixing with others to limit transmission.

People with COVID symptoms can take a rapid antigen test (RAT), ideally when symptoms start, then isolate until symptoms disappear. One negative RAT alone can’t rule out COVID if symptoms are still present, so test again 24–48 hours after your initial test if symptoms persist.

You can now test yourself for COVID, RSV and influenza in a combined RAT. But again, a negative test doesn’t rule out the virus. If your symptoms continue, test again 24–48 hours after the previous test.

If it’s hay fever, how do I treat it?

Treatment involves blocking the body’s histamine release, by taking antihistamine medication which helps reduce the symptoms.

Doctors, nurse practitioners and pharmacists can develop a hay fever care plan. This may include using a nasal spray containing a topical corticosteroid to help reduce the swelling inside the nose, which causes stuffiness or blockage.

Nasal sprays need to delivered using correct technique and used over several weeks to work properly. Often these sprays can also help lessen the itchy eyes of hay fever.

Drying bed linen and pyjamas inside during spring can lessen symptoms, as can putting a smear of Vaseline in the nostrils when going outside. Pollen sticks to the Vaseline, and gently blowing your nose later removes it.

People with asthma should also have an asthma plan, created by their doctor or nurse practitioner, explaining how to adjust their asthma reliever and preventer medications in hay fever seasons or on allergen exposure.

People with asthma also need to be alert for thunderstorms, where pollens can burst into tinier particles, be inhaled deeper in the lungs and cause a severe asthma attack, and even death.

What if it’s COVID, RSV or the flu?

Australians aged 70 and over and others with underlying health conditions who test positive for COVID are eligible for antivirals to reduce their chance of severe illness.

Most other people with COVID, RSV and influenza will recover at home with rest, fluids and paracetamol to relieve symptoms. However some groups are at greater risk of serious illness and may require additional treatment or hospitalisation.

For RSV, this includes premature infants, babies 12 months and younger, children under two who have other medical conditions, adults over 75, people with heart and lung conditions, or health conditions that lessens the immune system response.

For influenza, people at higher risk of severe illness are pregnant women, Aboriginal people, people under five or over 65 years, or people with long-term medical conditions, such as kidney, heart, lung or liver disease, diabetes and decreased immunity.

If you’re concerned about severe symptoms of COVID, RSV or influenza, consult your doctor or call 000 in an emergency.

If your symptoms are mild but persist, and you’re not sure what’s causing them, book an appointment with your doctor or nurse practitioner. Although hay fever season is here, we need to avoid spreading other serious infectious.

For more information, you can call the healthdirect helpline on 1800 022 222 (known as NURSE-ON-CALL in Victoria); use the online Symptom Checker; or visit healthdirect.gov.au or the Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy.

Deryn Thompson, Eczema and Allergy Nurse; Lecturer, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

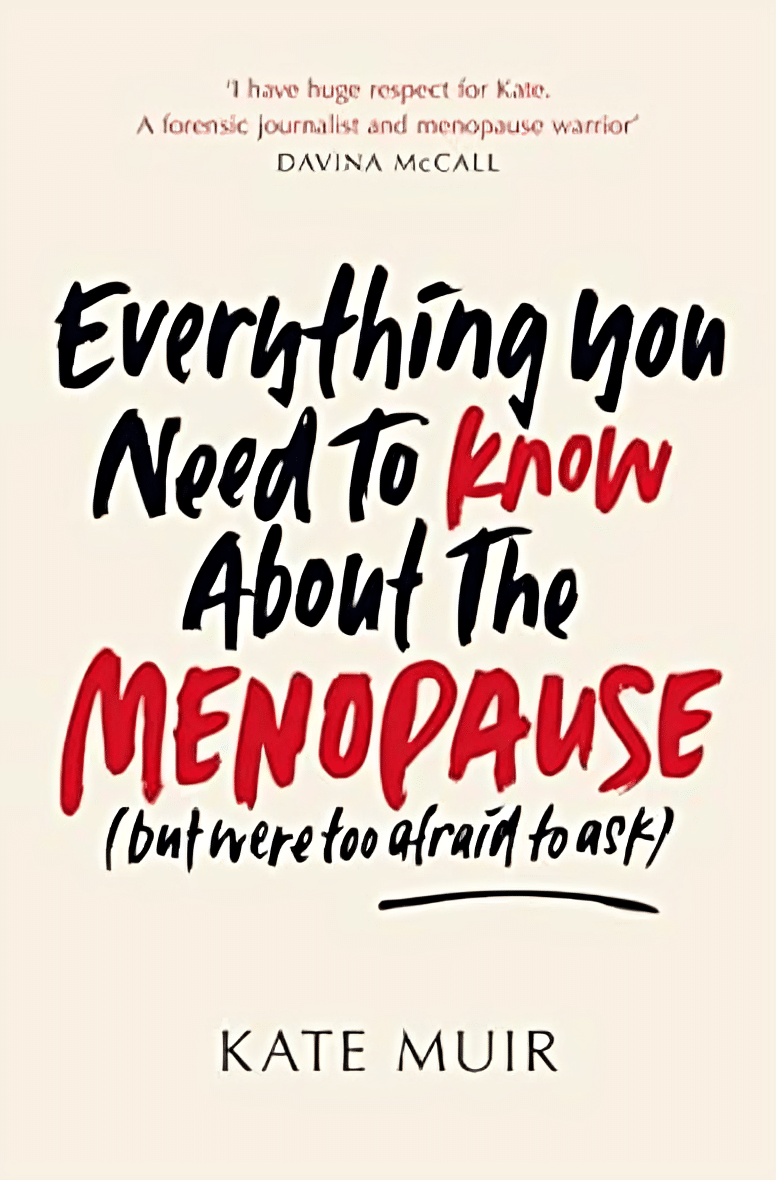

Everything You Need To Know About The Menopause – by Kate Muir

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Kate Muir has made a career out of fighting for peri-menopausal health to be taken seriously. Because… it’s actually far more serious than most people know.

What people usually know:

- No more periods

- Hot flushes

- “I dunno, some annoying facial hairs maybe”

The reality encompasses a lot more, and Muir covers topics including:

- Workplace struggles (completely unnecessary ones)

- Changes to our sex life (not usually good ones, by default!)

- Relationship between menopause and breast cancer

- Relationship between menopause and Alzheimer’s

“Wait”, you say, “correlation is not causation, that last one’s just an age thing”, and that’d be true if it weren’t for the fact that receiving Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) or not is strongly correlated with avoiding Alzheimer’s or not.

The breast cancer thing is not to be downplayed either. Taking estrogen comes with a stated risk of breast cancer… But what they don’t tell you, is that for many people, not taking it comes with a higher risk of breast cancer (but that’s not the doctor’s problem, in that case). It’s one of those situations where fear of litigation can easily overrule good science.

This kind of thing, and much more, makes up a lot of the meat of this book.

Hormonal treatment for the menopause is often framed in the wider world as a whimsical luxury, not a serious matter of health…. If you’ve ever wondered whether you might want something different, something better, as part of your general menopause plan (you have a plan for this important stage of your life, right?), this is a powerful handbook for you.

Additionally, if (like many!) you justifiably fear your doctor may brush you off (or in the case of mood disorders, may try to satisfy you with antidepressants to treat the symptom, rather than HRT to treat the cause), this book will arm you as necessary to help you get what you need.

Grab your copy of “Everything You Need To Know About The Menopause” from Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

CBD Against Diabetes!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝CBD for diabetes! I’ve taken CBD for body pain. Did no good. Didn’t pay attention as to diabetes. I’m type 1 for 62 years. Any ideas?❞

Thanks for asking! First up, for reference, here’s our previous main feature on the topic of CBD:

CBD Oil: What Does The Science Say?

There, we touched on CBD’s effects re diabetes:

in mice / in vitro / in humans

In summary, according to the above studies, it…

- lowered incidence of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. By this they mean that pancreatic function improved (reduced insulitis and reduced inflammatory Th1-associated cytokine production). Obviously this has strong implications for Type 1 Diabetes in humans—but so far, just that, implications (because you are not a mouse).

- attenuated high glucose-induced endothelial cell inflammatory response and barrier disruption. Again, this is promising, but it was an in vitro study in very controlled lab conditions, and sometimes “what happens in the Petri dish, stays in the Petri dish”—in order words, these results may or may not translate to actual living humans.

- Improved insulin response ← is the main take-away that we got from reading through their numerical results, since there was no convenient conclusion given. Superficially, this may be of more interest to those with type 2 diabetes, but then again, if you have T1D and then acquire insulin resistance on top of that, you stand a good chance of dying on account of your exogenous insulin no longer working. In the case of T2D, “the pancreas will provide” (more or less), T1D, not so much.

So, what else is there out there?

The American Diabetes Association does not give a glowing review:

❝There’s a lot of hype surrounding CBD oil and diabetes. There is no noticeable effect on blood glucose (blood sugar) or insulin levels in people with type 2 diabetes. Researchers continue to study the effects of CBD on diabetes in animal studies. ❞

~ American Diabetes Association

Source: ADA | CBD & Diabetes

Of course, that’s type 2, but most research out there is for type 2, or else have been in vitro or rodent studies (and not many of those, at that).

Here’s a relatively more recent study that echoes the results of the previous mouse study we mentioned; it found:

❝CBD-treated non-obese diabetic mice developed T1D later and showed significantly reduced leukocyte activation and increased FCD in the pancreatic microcirculation.

Conclusions: Experimental CBD treatment reduced markers of inflammation in the microcirculation of the pancreas studied by intravital microscopy. ❞

~ Dr. Christian Lehmann et al.

Read more: Experimental cannabidiol treatment reduces early pancreatic inflammation in type 1 diabetes

…and here’s a 2020 study (so, more recent again) that was this time rats, and/but still more promising, insofar as it was with rats that had full-blown T1D already:

Read in full: Two-weeks treatment with cannabidiol improves biophysical and behavioral deficits associated with experimental type-1 diabetes

Finally, a paper in July 2023 (so, since our previous article about CBD), looked at the benefits of CBD against diabetes-related complications (so, applicable to most people with any kind of diabetes), and concluded:

❝CBDis of great value in the treatment of diabetes and its complications. CBD can improve pancreatic islet function, reduce pancreatic inflammation and improve insulin resistance. For diabetic complications, CBD not only has a preventive effect but also has a therapeutic value for existing diabetic complications and improves the function of target organs❞

…before continuing:

❝However, the safety and effectiveness of CBD are still needed to prove. It should be acknowledged that the clinical application of CBD in the treatment of diabetes and its complications has a long way to go.

The dissecting of the pharmacology and therapeutic role of CBD in diabetes would guide the future development of CBD-based therapeutics for treating diabetes and diabetic complications❞

~ Ibid.

Now, the first part of that is standard ass-covering, and the second part of that is standard “please fund more studies please”. Nevertheless, we must also not fail to take heed—little is guaranteed, especially when it comes to an area of research where the science is still very young.

In summary…

It seems well worth a try, and with ostensibly nothing to lose except the financial cost of the CBD.

If you do, you might want to keep careful track of a) your usual diabetes metrics (blood sugar levels before and after meals, insulin taken), and b) when you took CBD, what dose, etc, so you can do some citizen science here.

Lastly: please remember our standard disclaimer; we are not doctors, let alone your doctors, so please do check with your endocrinologist before undertaking any such changes!

Want to read more?

You might like our previous main feature:

How To Prevent And Reverse Type 2 Diabetes ← obviously this will not prevent or reverse Type 1 Diabetes, but avoiding insulin resistance is good in any case!

If you’re not diabetic and you’ve perhaps been confused throughout this article, then firstly thank you for your patience, and secondly you might like this quick primer:

The Sweet Truth About Diabetes: Debunking Diabetes Myths! ← this gives a simplified but fair overview of types 1 & 2

(for space, we didn’t cover the much less common types 3 & 4; perhaps another time we will)

Meanwhile, take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gut Health 101

We have so many microorganisms inside us, that by cell count, their cells outnumber ours more than ten-to-one. By gene count, we have 23,000 and they have more than 3,000,000. In effect, we are more microbe than we are human. And, importantly: they form a critical part of what keeps our overall organism ticking on.

Read all about it: The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health

Our trillions of tiny friends keep us alive, so it really really pays to return the favor.

But how?

Probiotics and fermented foods

You probably guessed this one, but it’d be remiss not to mention it first. It’s no surprise that probiotics help; the clue is in the name. In short, they help add diversity to your microbiome (that’s a good thing).

Read from the NIH: Probiotics: What You Need To Know

As for fermented foods, not every fermented food will boost your microbiota, but great options include…

- Fermented vegetables (sauerkraut, pickles, etc)

- You’ll often hear kimchi mentioned; that is also pickled vegetables, usually mostly cabbage. It’s just the culinary experience that differs. Unlike sauerkraut, kimchi is usually spiced, for example.

- Kombucha (a fermented sweet tea)

- Miso & tempeh (different preparations of fermented soy)

The health benefits vary based on the individual strains of bacteria involved in the fermentation, so don’t get too caught up on which is best.

The best one is the one you enjoy, because then you’ll have it regularly!

Feed them plenty of prebiotic fibers

Those probiotics you took? The bacteria in them eat the fiber that you can’t digest without them. So, feed them those sorts of fibers.

Great options include:

- Bananas

- Garlic

- Onions

- Whole grains

Read more: Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health

Don’t feed them sugar and sweeteners

Sugar and (and, counterintuitively, aspartame) can cause unfortunate gut microbe imbalances. Put simply, they kill some of your friends and feed some of your enemies. For example…

Candida, which we all have in us to some degree, feeds on sugar (including the sugar formed from breaking down alcohol, by the way) and refined carbs. Then it grows, and puts its roots through your intestinal walls, linking with your neural system. Then it makes you crave the very things that will feed it and allow it to put bigger holes in your intestinal walls.

Do not feed the Candida.

Don’t believe us? Read: Candida albicans-Induced Epithelial Damage Mediates Translocation through Intestinal Barriers

(That’s scientist-speak for “Candida puts holes in your intestines, and stuff can then go through those holes”)

And as for how that comes about, it’s like we said:

❝Colonization of the intestine and translocation through the intestinal barrier are fundamental aspects of the processes preceding life-threatening systemic candidiasis. In this review, we discuss the commensal lifestyle of C. albicans in the intestine, the role of morphology for commensalism, the influence of diet, and the interactions with bacteria of the microbiota.❞

Source: Candida albicans as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen in the intestine

The usual five things

- Good diet (Mediterranean Diet is good; plant-based version of it is by far the best for this)

- Good exercise (yes, really)

- Good sleep (helps them, and they’ll help you get better sleep in return)

- Limit or eliminate alcohol consumption (what a shocker)

- Don’t smoke (it’s bad for everything, including gut health)

One last thing you should know:

If you’re used to having animal products in your diet, and make a sudden change to all plants, your gut will object very strongly. This is because your gut microbiome is used to animal products, and a plant-based diet will cause many helpful microbes to flourish in great abundance, and many less helpful microbes will starve and die. And they will make it officially Not Fun™ for you.

So, you have two options to consider:

- Do it anyway, and sit it out (and believe us, you’ll be sitting), get the change over with quickly, and enjoy the benefits and much happier gut that follows.

- Make the change gradual. Reduce portions of animal products slowly, have “Meatless Mondays” etc, and slowly make the change over. This—for most people—is pretty comfortable, easy, and effective.

And remember: the effects of these things we’ve talked about today compound when you do more than one of them, but if you don’t want to take probiotics or really hate kombucha or absolutely won’t consider a plant-based diet or struggle to give up sugar or alcohol, etc… Just do what you can do, and you’ll still have a net improvement!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

- Fermented vegetables (sauerkraut, pickles, etc)

-

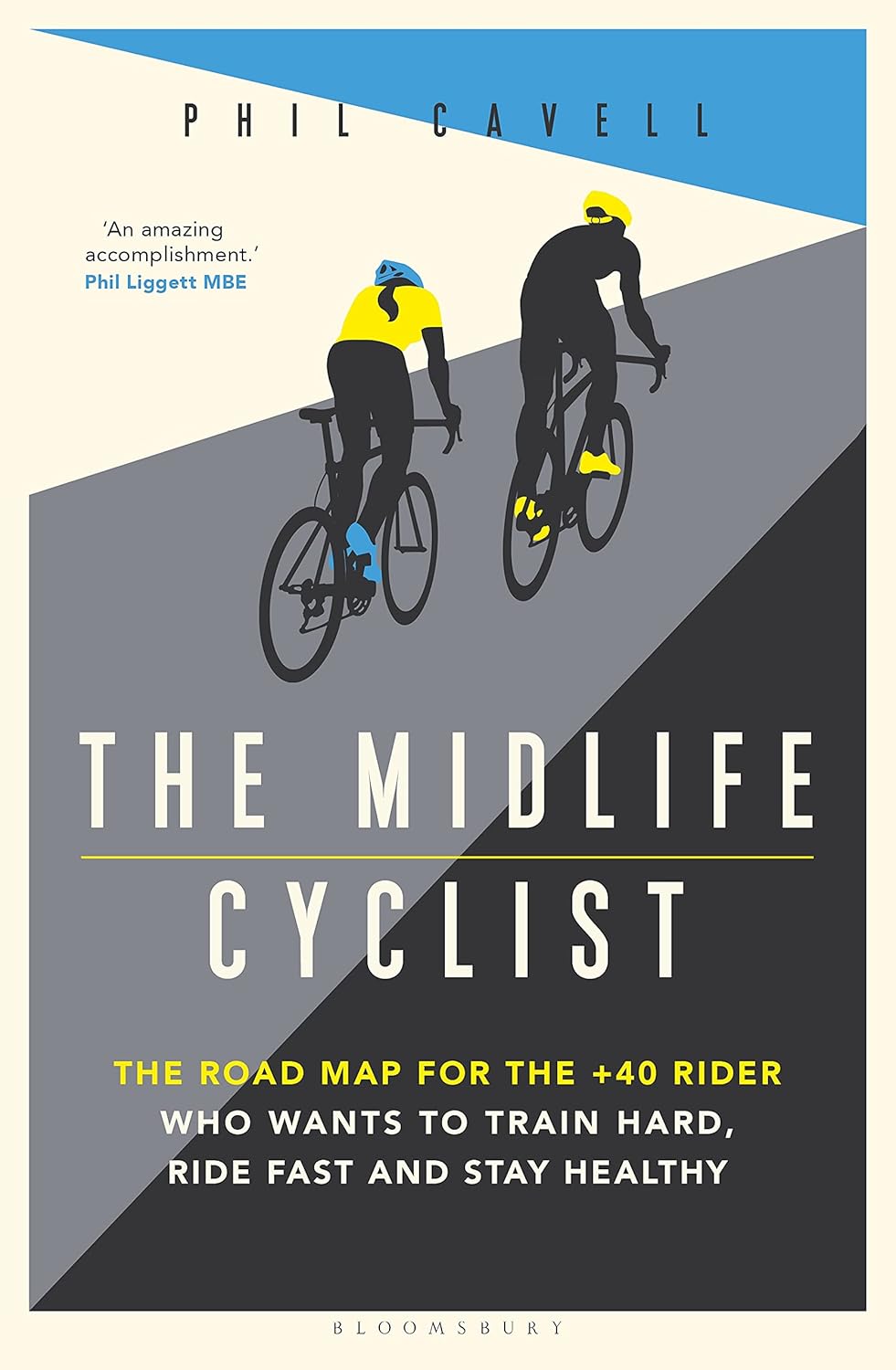

The Midlife Cyclist – by Phil Cavell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Whether stationary cycling in your living room, or competing in the Tour de France, there’s a lot more to cycling than “push the pedals”—if you want to get good benefits and avoid injury, in any case.

This book explores the benefits of different kinds of cycling, the biomechanics of various body positions, and the physiology of different kinds of performance, and the impact these things have on everything from your joints to your heart to your telomeres.

The style is very much conversational, with science included, and a readiness to acknowledge in cases where the author is guessing or going with a hunch, rather than something being well-evidenced. This kind of honesty is always good to see, and it doesn’t detract from where the science is available and clear.

One downside for some readers will be that while Cavell does endeavour to cover sex differences in various aspects of how they relate to the anatomy and physiology (mostly: the physiology) of cycling, the book is written from a male perspective and the author clearly understands that side of things better. For other readers, of course, this will be a plus.

Bottom line: if you enjoy cycling, or you’re thinking of taking it up but it seems a bit daunting because what if you do it wrong and need a knee replacement in a few years or what if you hurt your spine or something, then this is the book to set your mind at ease, and put you on the right track.

Click here to check out The Midlife Cyclist, and enjoy the cycle of life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Longevity Noodles

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Noodles may put the “long” into “longevity”, but most of the longevity here comes from the ergothioneine in the mushrooms! The rest of the ingredients are great too though, including the noodles themselves—soba noodles are made from buckwheat, which is not a wheat, nor even a grass (it’s a flowering plant), and does not contain gluten*, but does count as one of your daily portions of grains!

*unless mixed with wheat flour—which it shouldn’t be, but check labels, because companies sometimes cut it with wheat flour, which is cheaper, to increase their profit margin

You will need

- 1 cup (about 9 oz; usually 1 packet) soba noodles

- 6 medium portobello mushrooms, sliced

- 3 kale leaves, de-stemmed and chopped

- 1 shallot, chopped, or ¼ cup chopped onion of any kind

- 1 carrot, diced small

- 1 cup peas

- ½ bulb garlic, minced

- 2 tbsp rice vinegar

- 1 tsp grated fresh ginger

- 1 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- 1 tsp red chili flakes

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tbsp low-sodium soy sauce

- Avocado oil, for frying (alternatively: extra virgin olive oil or cold-pressed coconut oil are both perfectly good substitutions)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Cook the soba noodles per the packet instructions, rinse, and set aside

2) Heat a little oil in a skillet, add the shallot, and cook for about 2 minutes.

3) Add the carrot and peas and cook for 3 more minutes.

4) Add the mushrooms, kale, garlic, ginger, peppers, and vinegar, and cook for 1 more minute, stirring well.

5) Add the noodles, as well as the MSG or low-sodium soy sauce, and cook for yet 1 more minute.

6) Serve!

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Rice vs Buckwheat – Which is Healthier?

- The Magic Of Mushrooms: “The Longevity Vitamin” (That’s Not A Vitamin)

- Monosodium Glutamate: Sinless Flavor-Enhancer Or Terrible Health Risk?

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← 4/5 of these spices are in today’s dish!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: