Apple Cider Vinegar vs Apple Cider Vinegar Gummies – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apple cider vinegar (bottled) to apple cider vinegar (gummies), we picked the bottled.

Why?

There are several reasons!

The first reason is about dosage. For example, the sample we picked for apple cider vinegar gummies, boasts:

❝2 daily chewable gummies deliver 800 mg of Apple Cider Vinegar a day, equivalent to a teaspoon of liquid apple cider vinegar❞

That sounds good until you note that it’s recommended to take 1–2 tablespoons (not teaspoons) of apple vinegar. So this would need more like 4–8 gummies to make the dose. Suddenly, either that bottle of gummies is running out quickly, or you’re just not taking a meaningful dose and your benefits will likely not exceed placebo.

The other is reason about sugar. Most apple cider vinegar gummies are made with some kind of sugar syrup, often even high-fructose corn syrup, which is one of the least healthy foodstuffs (in the loosest sense of the word “foodstuffs”) known to science.

The specific brand we picked today was the best we can find; it used maltitol syrup.

Maltitol syrup, a corn derivative (and technically a sugar alcohol), has a Glycemic Index of 52, so it does raise blood sugars but not as much as sucrose would. However (and somewhat counterproductive to taking apple cider vinegar for gut health) it can cause digestive problems for many people.

And remember, you’re taking 4–8 gummies, so this is amounting to several tablespoons of the syrup by now.

On the flipside, apple cider vinegar itself has two main drawbacks, but they’re much less troublesome issues:

- many people don’t like the taste

- its acidic nature is not good for teeth

To this the common advice for both is to dilute it with water, thus diluting the taste and the acidity.

(this writer shoots hers from a shot glass, thus not bathing the teeth since it passes them “without touching the sides”; as for the taste, well, I find it invigorating—I do chase it with water, though to be sure of not leaving vinegar in my mouth)

Want to check them out for yourself?

Here they are:

Apple cider vinegar | Apple cider vinegar gummies

Want to know more about apple cider vinegar?

Check out:

- An Apple (Cider Vinegar) A Day…

- 10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars

- How To Recover Quickly From A Stomach Bug

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Coach’s Plan – by Mike Kavanagh

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A sports coach’s job is to prepare a plan, give it to the player(s), and hold them accountable to it. Change the strategy if needs be, call the shots. The job of the player(s) is then to follow those instructions.

If you have trouble keeping yourself accountable, Kavanagh argues that it can be good to separate how you approach things.

Not just “coach yourself”, but put yourself entirely in the coach’s shoes, as though you were a separate person, then switch back, and follow those instructions, trusting in your coach’s guidance.

The book also provides illustrative examples and guides the reader through some potential pitfalls—for example, what happens when morning you doesn’t want to do the things that evening you decided would be best?

The absolute backbone of this method is that it takes away the paralysing self-doubt that can occur when we second-guess ourselves mid-task.

In short, this book will fire up your enthusiasm and give you a reliable fall-back for when your motivation’s flagging.

Share This Post

-

When Doctors Make House Calls, Modern-Style!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

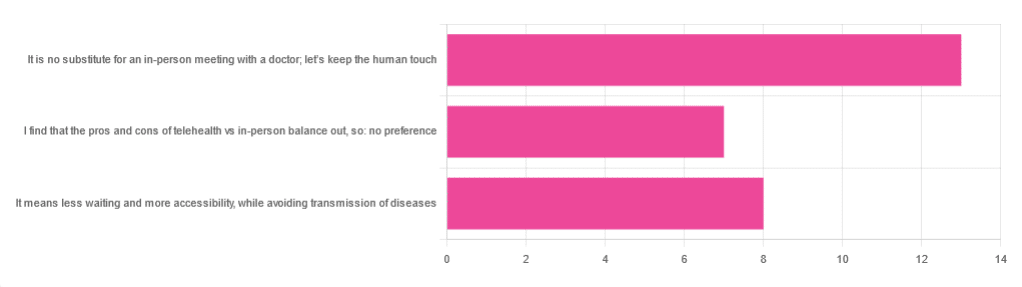

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you foryour opinion of telehealth for primary care consultations*, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 46% said “It is no substitute for an in-person meeting with a doctor; let’s keep the human touch”

- About 29% said “It means less waiting and more accessibility, while avoiding transmission of diseases”

- And 25 % said “I find that the pros and cons of telehealth vs in-person balance out, so: no preference”

*We specified that by “primary care” we mean the initial consultation with a non-specialist doctor, before receiving treatment or being referred to a specialist. By “telehealth” we mean by videocall or phonecall.

So, what does the science say?

A quick note first

Because telehealth was barely a thing (statistically speaking) before the first stages of the COVID pandemic, compared to how it is now, most of the science for this is young, and a lot of the science simply hasn’t been done yet, and/or has not been published yet, because the process can take years.

Because of this, some studies we do have aren’t specifically about primary care, and are sometimes about specialists. We think this should not affect the results much, but it bears highlighting.

Nevertheless, we’ll do what we can with the science we have!

Telehealth is more accessible than in-person consultations: True or False?

True, for most people. For example…

❝Data was found from a variety of emergency and non-emergency departments of primary, secondary, and specialised healthcare.

Satisfaction was high among recipients of healthcare, scoring 9-10 on a scale of 0-10 or ranging from 73.3% to 100%.

Convenience was rated high in every specialty examined. Satisfaction of clinicians was high throughout the specialities despite connection failure and concerns about confidentiality of information.❞

whereas…

❝Nonetheless, studies reported perception of increased barriers to accessing care and inequalities for vulnerable patients especially in older people❞

~ Ibid.

Source: Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review

Now, perception of those things does necessarily equate to an actual increased barrier, but it is reasonable that someone who thinks something is inaccessible will be less inclined to try to access it.

The quality of care provided via telehealth is as good as in-person: True or False?

True, ostensibly, with caveats. The caveats are:

- We’re going offreported patient satisfaction, not objective patient health outcomes (we found little* science as yet for the relative incidence of misdiagnosis, for example—which kind of thing will take time to be revealed).

- We’re also therefore speaking (as statistics do) for the significant majority of people. However, if we happen to be (statistically speaking) an insignificant minority, well, that just sucks for us personally.

*we did find some, but it wasn’t very helpful yet. For example:

An electronic trigger to detect telemedicine-related diagnostic errors

this one does look at the incidence of diagnostic errors, but provides no control group (i.e. otherwise-comparable in-person consultations) for comparison.

While most oft-considered demographic groups reported comparable patient satisfaction (per race, gender, and socioeconomic status, for example), there was one outlier variable, which was age (as we quoted from that first study above).

However!

Looking under the hood of these stats, it seems that age is not the real culprit, so much as technological illiteracy, which is heavily correlated with age:

❝Lower eHealth literacy is associated with more negative attitudes towards I/C technology in healthcare. This trend is consistent across diverse demographics and regions. ❞

Source: Meta-analysis: eHealth literacy and attitudes towards internet/computer technology

There are things that can be done at an in-person consultation that can’t be done by telehealth: True or False?

True, of course. It is incredibly rare that we will cite “common sense”, (as sometimes “common sense” is actually “common mistakes” and is simply and verifiably wrong), but in this case, as one 10almonds subscriber put it:

❝The doctor uses his five senses to assess. This cannot be attained over the phone❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

A quick note first: if your doctor is using their sense of taste to diagnose you, please get a different doctor, because they should definitely not be doing that!

Not in this century, anyway… Once upon a time, diabetes was diagnosed by urine-tasting (and yes, that was a fairly reliable method).

However, nowadays indeed a doctor will use sight, sound, touch, and sometimes even smell.

In a videocall we’re down to two of those senses (sight and sound), and in a phonecall, down to one (sound) and even that is hampered. Your doctor cannot, for example, use a stethoscope over the phone.

With this in mind, it really comes down to what you need from your doctor in that consultation.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is to be prescribed an antidepressant, that probably doesn’t need a full physical.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is a referral, chances are that’ll be fine by telehealth too.

- If your doctor is 99% sure that what you need is a verbal check-up (e.g. “How’s it been going for you, with the medication that I prescribed for you a month ago?”, then again, a call is probably fine.

If you have a worrying lump, or an unhappy bodily discharge, or an unexplained mysterious pain? These things, more likely an in-person check-up is in order.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Study links microplastics with human health problems – but there’s still a lot we don’t know

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mark Patrick Taylor, Macquarie University and Scott P. Wilson, Macquarie University

A recent study published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine has linked microplastics with risk to human health.

The study involved patients in Italy who had a condition called carotid artery plaque, where plaque builds up in arteries, potentially blocking blood flow. The researchers analysed plaque specimens from these patients.

They found those with carotid artery plaque who had microplastics and nanoplastics in their plaque had a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death (compared with carotid artery plaque patients who didn’t have any micro- or nanoplastics detected in their plaque specimens).

Importantly, the researchers didn’t find the micro- and nanoplastics caused the higher risk, only that it was correlated with it.

So, what are we to make of the new findings? And how does it fit with the broader evidence about microplastics in our environment and our bodies?

What are microplastics?

Microplastics are plastic particles less than five millimetres across. Nanoplastics are less than one micron in size (1,000 microns is equal to one millimetre). The precise size classifications are still a matter of debate.

Microplastics and nanoplastics are created when everyday products – including clothes, food and beverage packaging, home furnishings, plastic bags, toys and toiletries – degrade. Many personal care products contain microsplastics in the form of microbeads.

Plastic is also used widely in agriculture, and can degrade over time into microplastics and nanoplastics.

These particles are made up of common polymers such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene and polyvinyl chloride. The constituent chemical of polyvinyl chloride, vinyl chloride, is considered carcinogenic by the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Of course, the actual risk of harm depends on your level of exposure. As toxicologists are fond of saying, it’s the dose that makes the poison, so we need to be careful to not over-interpret emerging research.

A closer look at the study

This new study in the New England Journal of Medicine was a small cohort, initially comprising 304 patients. But only 257 completed the follow-up part of the study 34 months later.

The study had a number of limitations. The first is the findings related only to asymptomatic patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy (a procedure to remove carotid artery plaque). This means the findings might not be applicable to the wider population.

The authors also point out that while exposure to microplastics and nanoplastics has been likely increasing in recent decades, heart disease rates have been falling.

That said, the fact so many people in the study had detectable levels of microplastics in their body is notable. The researchers found detectable levels of polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride (two types of plastic) in excised carotid plaque from 58% and 12% of patients, respectively.

These patients were more likely to be younger men with diabetes or heart disease and a history of smoking. There was no substantive difference in where the patients lived.

Inflammation markers in plaque samples were more elevated in patients with detectable levels of microplastics and nanoplastics versus those without.

Microplastics are created when everyday products degrade. JS14/Shutterstock And, then there’s the headline finding: patients with microplastics and nanoplastics in their plaque had a higher risk of having what doctors call “a primary end point event” (non-fatal heart attack, non-fatal stroke, or death from any cause) than those who did not present with microplastics and nanoplastics in their plaque.

The authors of the study note their results “do not prove causality”.

However, it would be remiss not to be cautious. The history of environmental health is replete with examples of what were initially considered suspect chemicals that avoided proper regulation because of what the US National Research Council refers to as the “untested-chemical assumption”. This assumption arises where there is an absence of research demonstrating adverse effects, which obviates the requirement for regulatory action.

In general, more research is required to find out whether or not microplastics cause harm to human health. Until this evidence exists, we should adopt the precautionary principle; absence of evidence should not be taken as evidence of absence.

Global and local action

Exposure to microplastics in our home, work and outdoor environments is inevitable. Governments across the globe have started to acknowledge we must intervene.

The Global Plastics Treaty will be enacted by 175 nations from 2025. The treaty is designed, among other things, to limit microplastic exposure globally. Burdens are greatest especially in children and especially those in low-middle income nations.

In Australia, legislation ending single use plastics will help. So too will the increased rollout of container deposit schemes that include plastic bottles.

Microplastics pollution is an area that requires a collaborative approach between researchers, civil societies, industry and government. We believe the formation of a “microplastics national council” would help formulate and co-ordinate strategies to tackle this issue.

Little things matter. Small actions by individuals can also translate to significant overall environmental and human health benefits.

Choosing natural materials, fabrics, and utensils not made of plastic and disposing of waste thoughtfully and appropriately – including recycling wherever possible – is helpful.

Mark Patrick Taylor, Chief Environmental Scientist, EPA Victoria; Honorary Professor, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University and Scott P. Wilson, Research Director, Australian Microplastic Assessment Project (AUSMAP); Honorary Senior Research Fellow, School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Proteins Of The Week

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This week’s news round-up is, entirely by chance, somewhat protein-centric in one form or another. So, check out the bad, the very bad, the mostly good, the inconvenient, and the worst:

Mediterranean diet vs the menopause

Researchers looked at hundreds of women with an average age of 51, and took note of their dietary habits vs their menopause symptoms. Most of them were consuming soft drinks and red meat, and not good in terms of meeting the recommendations for key food groups including vegetables, legumes, fruit, fish and nuts, and there was an association between greater adherence to Mediterranean diet principles, and better health.

Read in full: Fewer soft drinks and less red meat may ease menopause symptoms: Study

Related: Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet

Listeria in meat

This one’s not a study, but it is relevant important news. The headline pretty much says it all, so if you don’t eat meat, this isn’t one you need to worry about any further than that. If you do eat meat, though, you might want to check out the below article to find out whether the meat you eat might be carrying listeria:

Read in full: Almost 10 million pounds of meat recalled due to Listeria danger

Related: Frozen/Thawed/Refrozen Meat: How Much Is Safety, And How Much Is Taste?

Brawn and brain?

A study looked at cognitively healthy older adults (of whom, 57% women), and found an association between their muscle strength and their psychological wellbeing. Note that when we said “cognitively healthy”, this means being free from dementia etc—not necessarily psychologically health in all respects, such as also being free from depression and enjoying good self-esteem.

Read in full: Study links muscle strength and mental health in older adults

Related: Staying Strong: Tips To Prevent Muscle Loss With Age

The protein that blocks bone formation

This one’s more clinical but definitely of interest to any with osteoporosis or at high risk of osteoporosis. Researchers identified a specific protein that blocks osteoblast function, thus more of this protein means less bone production. Currently, this is not something that we as individuals can do anything about at home, but it is promising for future osteoporosis meds development.

Read in full: Protein blocking bone development could hold clues for future osteoporosis treatment

Related: Which Osteoporosis Medication, If Any, Is Right For You?

Rabies risk

People associate rabies with “rabid dogs”, but the biggest rabies threat is actually bats, and they don’t even need to necessarily bite you to confer the disease (it suffices to have licked the skin, for instance—and bats are basically sky-puppies who will lick anything). Because rabies has a 100% fatality rate in unvaccinated humans, this is very serious. This means that if you wake up and there’s a bat in the house, it doesn’t matter if it hasn’t bitten anyone; get thee to a hospital (where you can get the vaccine before the disease takes hold; this will still be very unpleasant but you’ll probably survive so long as you get the vaccine in time).

Read in full: What to know about bats and rabies

Related: Dodging Dengue In The US ← much less serious than rabies, but still not to be trifled with—particularly noteworthy if you’re in an area currently affected by floodwaters or even just unusually heavy rain, by the way, as this will leave standing water in which mosquitos breed.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Healthiest Bread Recipe You’ll Probably Find

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝[About accidental scalding with water] Is cold water actually the best immediate treatment for a burn? Maybe there is something better, or something I should apply after the cold water.❞

If this is a case of spilled tea or similar—as in your story, which (apologies) we clipped for brevity—indeed, cold running water is best, and nothing else should be needed. It’s up to you whether you want to invest the time based on the extent of the scalding, but 10 minutes is recommended to minimize tissue damage.

If it’s a more severe scalding or burning, seek medical attention immediately. If it’s a burn to anywhere other than the airway, cold running water is still best for 10 minutes, but if you have to choose between that and professional medical attention, don’t delay the help.

If it’s a burn you’ve given 10 minutes of cold running water and it still hurts and/or has blistered, cover it in a sterile, non-adhesive dressing that extends well beyond the visible burn (because the actual damage probably extends further, and you don’t want to find this out the hard way later). If the burn is to the face, do still irrigate but not cover it; wait for help.

Do not apply any kind of cream, lotion, oil, etc. No matter how tempting, no matter where the burn is.

All of the above also goes for splashed oil, chemical burns, and electrical burns too (but obviously, make sure to get away from the electricity first).

Source: this ex-military writer was trained for this sort of thing and, suffice it to say, has dealt with more serious things than spilled tea before now.

Legal note: notwithstanding the above, we are a health science newsletter, not paramedics. Also, circumstances may differ, and best practices may change. In the case of serious injury, call emergency services first, and follow their instructions over ours.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Immunity – by Dr. William Paul

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book gives a very person-centric (i.e., focuses on the contributions of named individuals) overview of advances in the field of immunology—up to its publication date in 2015. So, it’s not cutting edge, but it is very good at laying the groundwork for understanding more recent advances that occur as time goes by. After all, immunology is a field that never stands still.

We get a good grounding in how our immune system works (and how it doesn’t), the constant arms race between pathogens and immune responses, and the complexities of autoimmune disorders and—which is functionally in an overlapping category of disease—cancer. And, what advances we can expect soon to address those things.

Given the book was published 8 years ago, how did it measure up? Did we get those advances? Well, for the mostpart yes, we have! Some are still works in progress. But, we’ve also had obvious extra immunological threats in years since, which have also resulted in other advances along the way!

If the book has a downside, it’s that sometimes the author can be a little too person-centric. It’s engaging to focus on human characters, and helps us bring information to life; name-dropping to excess, along with awards won, can sometimes feel a little like the book was co-authored by Tahani Al-Jamil.

Nevertheless, it certainly does keep the book from getting too dry!

Bottom line: this book is a great overview of immunology and immunological research, for anyone who wants to understand these things better.

Click here to check out Immunity, and boost your knowledge of yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: