Are You Eating AGEs?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Trouble of the AGEs

Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs) are the result of the chemical process of glycation, which can occur in your body in response to certain foods you ate, or you can consume them directly, if you eat animal products that contained them (because we’re not special and other animals glycate too, especially mammals such as pigs, cows, and sheep).

As a double-whammy, if you cook animal products (especially without water, such as by roasting or frying), extra AGEs will form during cooking.

When proteinous and/or fatty food turns yellow/golden/brown during cooking, that’s generally glycation.

If there’s starch present, some or all of that yellow/golden/brown stuff will be a Maillard Reaction Product (MRP), such as acrylamide. That’s not exactly a health food, but it’s nowhere near being even in the same ballpark of badness.

In short, during cooking:

- Proteinous/fatty food turns yellow/golden/brown = probably an AGE

- Starchy food turns yellow/golden/brown = probably a MRP

The AGEs are far worse.

What’s so bad about AGEs?

Let’s do a quick tour of some studies:

- The role of advanced glycation end-products in retinal ageing and disease

- Advanced glycation end-products and their circulating receptors predict cardiovascular disease mortality in older women

- Elevated serum advanced glycation end-products in obese indicate risk for the metabolic syndrome: a link between healthy and unhealthy obesity?

- Increased levels of serum advanced glycation end-products in women with polycystic ovary syndrome

- Advanced glycation end-products and their involvement in liver disease

- Effects of advanced glycation end-products on renal fibrosis and oxidative stress

- Role of advanced glycation end-products and oxidative stress in vascular complications in diabetes

- Cancer malignancy is enhanced by advanced glycation end-products

- Advanced glycation end-products in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease

We could keep going, but you probably get the picture!

What should we do about it?

There are three main ways to reduce serum AGE levels:

Reduce or eliminate consumption of animal products

Especially mammalian animal products, such as from pigs, cows, and sheep, especially their meat. Processed versions are even worse! So, steak is bad, but bacon and sausages are literally top-tier bad.

Cook wet

Dry cooking (which includes frying, and especially includes deep fat frying, which is worse than shallow frying which is worse than air frying) produces far more AGEs than cooking with methods that involve water (boiling, steaming, slow-cooking, etc).

As a bonus, adding acidic ingredients (e.g. vinegar, lemon juice, tomato juice) can halve the amount of AGEs produced.

Consume antioxidants

Our body does have some ability to deal with AGEs, but that ability has its limits, and our body can be easily overwhelmed if we consume foods that are bad for it. So hopefully you’ll tend towards a plant-based diet, but whether you do or don’t:

You can give your body a hand by consuming antioxidant foods and drinks (such as berries, tea/coffee, and chocolate), and/or taking supplements.

Want to know more about the science of this?

Check out…

Advanced Glycation End-Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What pathogen might spark the next pandemic? How scientists are preparing for ‘disease X’

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Before the COVID pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) had made a list of priority infectious diseases. These were felt to pose a threat to international public health, but where research was still needed to improve their surveillance and diagnosis. In 2018, “disease X” was included, which signified that a pathogen previously not on our radar could cause a pandemic.

While it’s one thing to acknowledge the limits to our knowledge of the microbial soup we live in, more recent attention has focused on how we might systematically approach future pandemic risks.

Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously talked about “known knowns” (things we know we know), “known unknowns” (things we know we don’t know), and “unknown unknowns” (the things we don’t know we don’t know).

Although this may have been controversial in its original context of weapons of mass destruction, it provides a way to think about how we might approach future pandemic threats.

Anna Shvets/Pexels Influenza: a ‘known known’

Influenza is largely a known entity; we essentially have a minor pandemic every winter with small changes in the virus each year. But more major changes can also occur, resulting in spread through populations with little pre-existing immunity. We saw this most recently in 2009 with the swine flu pandemic.

However, there’s a lot we don’t understand about what drives influenza mutations, how these interact with population-level immunity, and how best to make predictions about transmission, severity and impact each year.

The current H5N1 subtype of avian influenza (“bird flu”) has spread widely around the world. It has led to the deaths of many millions of birds and spread to several mammalian species including cows in the United States and marine mammals in South America.

Human cases have been reported in people who have had close contact with infected animals, but fortunately there’s currently no sustained spread between people.

While detecting influenza in animals is a huge task in a large country such as Australia, there are systems in place to detect and respond to bird flu in wildlife and production animals.

Scientists are continually monitoring a range of pathogens with pandemic potential. Edward Jenner/Pexels It’s inevitable there will be more influenza pandemics in the future. But it isn’t always the one we are worried about.

Attention had been focused on avian influenza since 1997, when an outbreak in birds in Hong Kong caused severe disease in humans. But the subsequent pandemic in 2009 originated in pigs in central Mexico.

Coronaviruses: an ‘unknown known’

Although Rumsfeld didn’t talk about “unknown knowns”, coronaviruses would be appropriate for this category. We knew more about coronaviruses than most people might have thought before the COVID pandemic.

We’d had experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) causing large outbreaks. Both are caused by viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID. While these might have faded from public consciousness before COVID, coronaviruses were listed in the 2015 WHO list of diseases with pandemic potential.

Previous research into the earlier coronaviruses proved vital in allowing COVID vaccines to be developed rapidly. For example, the Oxford group’s initial work on a MERS vaccine was key to the development of AstraZeneca’s COVID vaccine.

Similarly, previous research into the structure of the spike protein – a protein on the surface of coronaviruses that allows it to attach to our cells – was helpful in developing mRNA vaccines for COVID.

It would seem likely there will be further coronavirus pandemics in the future. And even if they don’t occur at the scale of COVID, the impacts can be significant. For example, when MERS spread to South Korea in 2015, it only caused 186 cases over two months, but the cost of controlling it was estimated at US$8 billion (A$11.6 billion).

COVID could be regarded as an ‘unknown known’. Markus Spiske/Pexels The 25 viral families: an approach to ‘known unknowns’

Attention has now turned to the known unknowns. There are about 120 viruses from 25 families that are known to cause human disease. Members of each viral family share common properties and our immune systems respond to them in similar ways.

An example is the flavivirus family, of which the best-known members are yellow fever virus and dengue fever virus. This family also includes several other important viruses, such as Zika virus (which can cause birth defects when pregnant women are infected) and West Nile virus (which causes encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain).

The WHO’s blueprint for epidemics aims to consider threats from different classes of viruses and bacteria. It looks at individual pathogens as examples from each category to expand our understanding systematically.

The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has taken this a step further, preparing vaccines and therapies for a list of prototype pathogens from key virus families. The goal is to be able to adapt this knowledge to new vaccines and treatments if a pandemic were to arise from a closely related virus.

Pathogen X, the ‘unknown unknown’

There are also the unknown unknowns, or “disease X” – an unknown pathogen with the potential to trigger a severe global epidemic. To prepare for this, we need to adopt new forms of surveillance specifically looking at where new pathogens could emerge.

In recent years, there’s been an increasing recognition that we need to take a broader view of health beyond only thinking about human health, but also animals and the environment. This concept is known as “One Health” and considers issues such as climate change, intensive agricultural practices, trade in exotic animals, increased human encroachment into wildlife habitats, changing international travel, and urbanisation.

This has implications not only for where to look for new infectious diseases, but also how we can reduce the risk of “spillover” from animals to humans. This might include targeted testing of animals and people who work closely with animals. Currently, testing is mainly directed towards known viruses, but new technologies can look for as yet unknown viruses in patients with symptoms consistent with new infections.

We live in a vast world of potential microbiological threats. While influenza and coronaviruses have a track record of causing past pandemics, a longer list of new pathogens could still cause outbreaks with significant consequences.

Continued surveillance for new pathogens, improving our understanding of important virus families, and developing policies to reduce the risk of spillover will all be important for reducing the risk of future pandemics.

This article is part of a series on the next pandemic.

Allen Cheng, Professor of Infectious Diseases, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

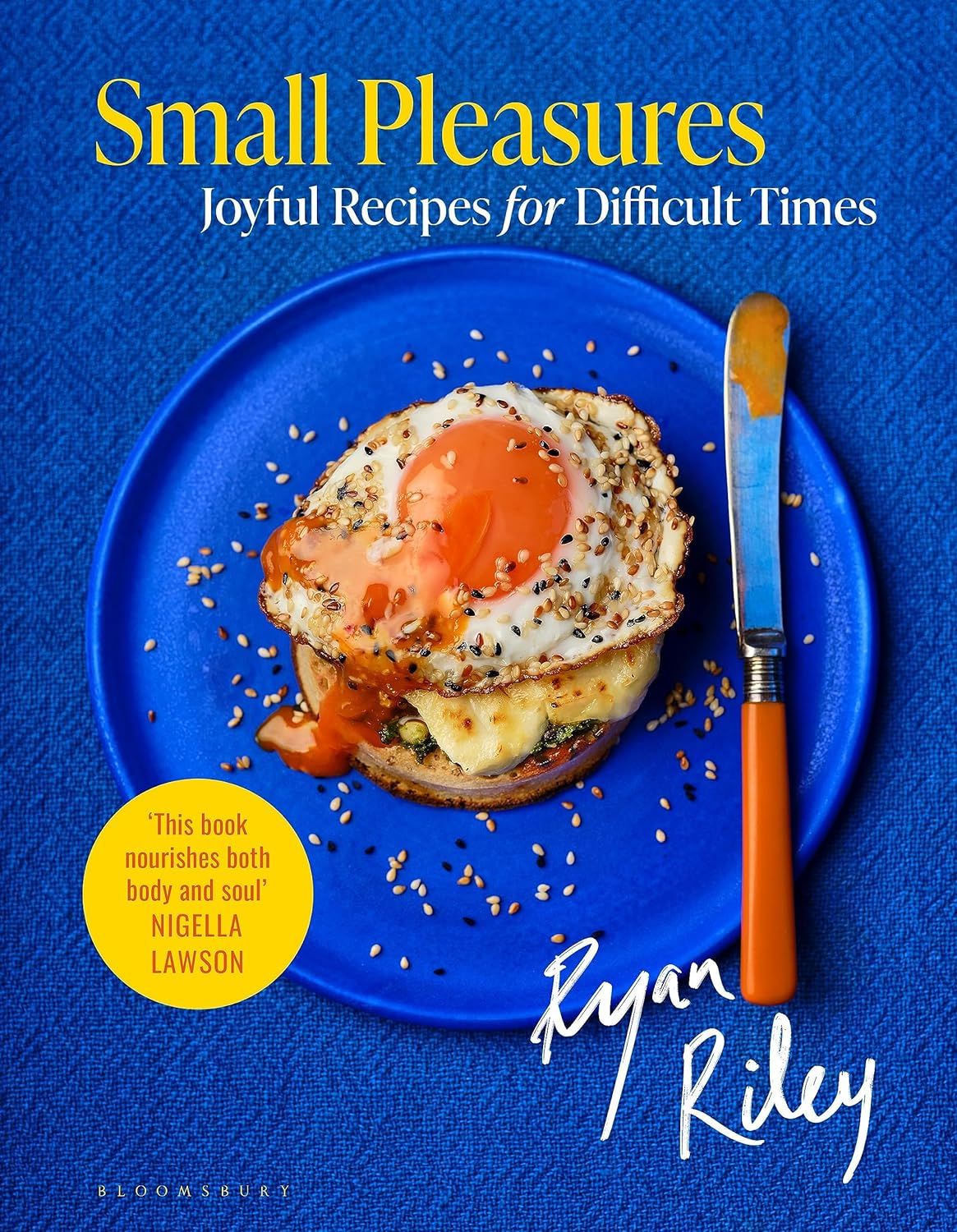

Small Pleasures – by Ryan Riley

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When Hippocrates said “let food be thy medicine, and let medicine be thy food”, he may or may not have had this book in mind.

In terms of healthiness, this one’s not the very most nutritionist-approved recipe book we’ve ever reviewed. It’s not bad, to be clear!

But the physical health aspect is secondary to the mental health aspects, in this one, as you’ll see. And as we say, “mental health is also just health”.

The book is divided into three sections:

- Comfort—for when you feel at your worst, for when eating is a chore, for when something familiar and reassuring will bring you solace. Here we find flavor and simplicity; pastas, eggs, stews, potato dishes, and the like.

- Restoration—for when your energy needs reawakening. Here we find flavors fresh and tangy, enlivening and bright. Things to make you feel alive.

- Pleasure—while there’s little in the way of health-food here, the author describes the dishes in this section as “a love letter to yourself; they tell you that you’re special as you ready yourself to return to the world”.

And sometimes, just sometimes, we probably all need a little of that.

Bottom line: if you’d like to bring a little more joie de vivre to your cuisine, this book can do that.

Click here to check out Small Pleasures, and rekindle joy in your kitchen!

Share This Post

-

Gentler Hair Health Options

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hair, Gently

We have previously talked about the medicinal options for combatting the thinning hair that comes with age especially for men, but also for a lot of women. You can read about those medicinal options here:

Hair-Loss Remedies, By Science

We also did a whole supplement spotlight research review for saw palmetto! You can read about how that might help you keep your hair present and correct, here:

One Man’s Saw Palmetto Is Another Woman’s Serenoa Repens

Today we’re going to talk options that are less “heavy guns”, and/but still very useful.

Supplementation

First, the obvious. Taking vitamins and minerals, especially biotin, can help a lot. This writer takes 10,000µg (that’s micrograms, not milligrams!) biotin gummies, similar to this example product on Amazon (except mine also has other vitamins and minerals in, but the exact product doesn’t seem to be available on Amazon).

When thinking “what vitamins and minerals help hair?”, honestly, it’s most of them. So, focus on the ones that count for the most (usually: biotin and zinc), and then cover your bases for the rest with good diet and additional supplementation if you wish.

Caffeine (topical)

It may feel silly, giving one’s hair a stimulant, but topical caffeine application really does work to stimulate hair growth. And not “just a little help”, either:

❝Specifically, 0.2% topical caffeine-based solutions are typically safe with very minimal adverse effects for long-term treatment of AGA, and they are not inferior to topical 5% minoxidil therapy❞

(AGA = Androgenic Alopecia)

Argan oil

As with coconut oil, argan oil is great on hair. It won’t do a thing to improve hair growth or decrease hair shedding, but it will help you hair stay moisturized and thus reduce breakage—thus, may not be relevant for everyone, but for those of us with hair long enough to brush, it’s important.

Bonus: get an argan oil based hair serum that also contains keratin (the protein used to make hair), as this helps strengthen the hair too.

Here’s an example product on Amazon

Silk pillowcases

Or a silk hair bonnet to sleep in! They both do the same thing, which is prevent damaging the hair in one’s sleep by reducing the friction that it may have when moving/turning against the pillow in one’s sleep.

- Pros of the bonnet: if you have lots of hair and a partner in bed with you, your hair need not be in their face, and you also won’t get it caught under you or them.

- Pros of the pillowcase: you don’t have to wear a bonnet

Both are also used widely by people without hair loss issues, but with easily damaged and/or tangled hair—Black people especially with 3C or tighter curls in particular often benefit from this. Other people whose hair is curly and/or gray also stand to gain a lot.

Here are Amazon example products of a silk pillowcase (it’s expensive, but worth it) and a silk bonnet, respectively

Want to read more?

You might like this article:

From straight to curly, thick to thin: here’s how hormones and chemotherapy can change your hair

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

When You “Can’t Complain”

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A Bone To Pick… Up And Then Put Back Where We Found It

In today’s Psychology Sunday feature, we’re going to be flipping the narrative on gratitude, by tackling it from the other end.

We have, by the way, written previously about gratitude, and what mistakes to avoid, in one of our pieces on positive psychology:

How To Get Your Brain On A More Positive Track (Without Toxic Positivity)

“Can’t complain”

Your mission, should you choose to accept it (and come on, who doesn’t like a challenge?) is to go 21 days without complaining (to anyone, including yourself, about anything). If you break your streak, that’s ok, just start again!

Why?

Complaining is (unsurprisingly) inversely correlated with happiness, in a self-perpetuating cycle:

Pet Peeves and Happiness: How Do Happy People Complain?

And if a stronger motivation is required, there’s a considerable inverse correlation between all-cause happiness and all-cause mortality, even when potential confounding factors (e.g., chronic health conditions, socioeconomic status, etc) are controlled for, and especially as we get older:

Investing in Happiness: The Gerontological Perspective

How?

You may have already formulated some objections by this point, for example:

- Am I supposed to tell my doctor/therapist “I’m fine thanks; how are you?”

- Some things are worthy of complaint; should I be silent?

But both of these issues (communication, and righteousness) have answers:

On communication:

There is a difference between complaining, and giving the necessary information in answer to a question—or even volunteering such information.

For example, when our site went down yesterday, some of you wrote to us to let us know the links weren’t working. There is a substantive difference (semantic, ontological, and teleological) between:

- ❝The content was great but the links in “you may have missed” did not work.❞ ← a genuine piece of feedback we received (thank you!)

- ❝Wasted my time, couldn’t read your articles! Unsubscribing, and I hope your socks get wet tomorrow!❞ ← nobody said this; our subscribers are lovely (thank you)

- Note that the former wasn’t a complaint, it was genuinely helpful feedback, without which we might not have noticed the problem and fixed it.

- The latter was a complaint, and also (like many complaints) didn’t even address the actual problem usefully.

What makes it a complaint or not is not the information conveyed, but the tone and intention. So for example:

“You’ve only done half the job I asked you to!” → “Thank you for doing the first half of this job, could you please do the other half now?”

Writer’s anecdote: my washing machine needs a part replaced; the part was ordered two weeks ago and I was told it would take a week to arrive. It’s been two weeks, so tomorrow I will not complain, but I will politely ask whether they have any information about the delay, and a new estimated time of arrival. Because you know what? Whatever the delay is, complaining won’t make it arrive last week!

On righteousness:

Indeed, some things are very worthy of complaint. But are you able to effect a solution by complaining? If not, then it’s just hot air. And venting isn’t without its own merits (we touched on the benefits of emotional catharsis recently), but that should be a mindful choice when you choose to do that, not a matter of reactivity.

Complaining is a subset of criticizing, and criticizing can be done without the feeling and intent of complaining. However, it too should definitely be measured and considered, responsive, not reactive. This itself could be the topic for another main feature, but for now, here’s a Psychology Today article that at least explains the distinction in more words than we have room for here:

React vs Respond: What’s the difference?

This, by the way, also goes the same for engaging in social and political discourse. It’s easy to get angry and reactive, but it’s good to take a moment to pick your battles, and by all means fight for what you believe in, and/but also do so responsively rather than reactively.

Not only will your health thank you, but you’re also more likely to “win friends and influence people” and all that!

What gets measured, gets done

Find a way of tracking your streak. There are apps for that, like this one, or you could find a low-tech method you prefer.

Bonus tip: if you do mess up and complain, and you realize as you’re doing it, take a moment to take a breath and correct yourself in the moment.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can kimchi really help you lose weight? Hold your pickle. The evidence isn’t looking great

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Fermented foods have become popular in recent years, partly due to their perceived health benefits.

For instance, there is some evidence eating or drinking fermented foods can improve blood glucose control in people with diabetes. They can lower blood lipid (fats) levels and blood pressure in people with diabetes or obesity. Fermented foods can also improve diarrhoea symptoms.

But can they help you lose weight, as a recent study suggests? Let’s look at the evidence.

Remind me, what are fermented foods?

Fermented foods are ones prepared when microbes (bacteria and/or yeast) ferment (or digest) food components to form new foods. Examples include yoghurt, cheese, kefir, kombucha, wine, beer, sauerkraut and kimchi.

As a result of fermentation, the food becomes acidic, extending its shelf life (food-spoilage microbes are less likely to grow under these conditions). This makes fermentation one of the earliest forms of food processing.

Fermentation also leads to new nutrients being made. Beneficial microbes (probiotics) digest nutrients and components in the food to produce new bioactive components (postbiotics). These postbiotics are thought to contribute to the health benefits of the fermented foods, alongside the health benefits of the bacteria themselves.

What does the evidence say?

A study published last week has provided some preliminary evidence eating kimchi – the popular Korean fermented food – is associated with a lower risk of obesity in some instances. But there were mixed results.

The South Korean study involved 115,726 men and women aged 40-69 who reported how much kimchi they’d eaten over the previous year. The study was funded by the World Institute of Kimchi, which specialises in researching the country’s national dish.

Eating one to three servings of any type of kimchi a day was associated with a lower risk of obesity in men.

Men who ate more than three serves a day of cabbage kimchi (baechu) were less likely to have obesity and abdominal obesity (excess fat deposits around their middle). And women who ate two to three serves a day of baechu were less likely to have obesity and abdominal obesity.

Eating more radish kimchi (kkakdugi) was associated with less abdominal obesity in both men and women.

However, people who ate five or more serves of any type of kimchi weighed more, had a larger waist sizes and were more likely to be obese.

The study had limitations. The authors acknowledged the questionnaire they used may make it difficult to say exactly how much kimchi people actually ate.

The study also relied on people to report past eating habits. This may make it hard for them to accurately recall what they ate.

This study design can also only tell us if something is linked (kimchi and obesity), not if one thing causes another (if kimchi causes weight loss). So it is important to look at experimental studies where researchers make changes to people’s diets then look at the results.

How about evidence from experimental trials?

There have been several experimental studies looking at how much weight people lose after eating various types of fermented foods. Other studies looked at markers or measures of appetite, but not weight loss.

One study showed the stomach of men who drank 1.4 litres of fermented milk during a meal took longer to empty (compared to those who drank the same quantity of whole milk). This is related to feeling fuller for longer, potentially having less appetite for more food.

Another study showed drinking 200 millilitres of kefir (a small glass) reduced participants’ appetite after the meal, but only when the meal contained quickly-digested foods likely to make blood glucose levels rise rapidly. This study did not measure changes in weight.

Kefir, a fermented milk drink, reduced people’s appetite.

Ildi Papp/ShutterstockAnother study looked at Indonesian young women with obesity. Eating tempeh (a fermented soybean product) led to changes in an appetite hormone. But this did not impact their appetite or whether they felt full. Weight was not measured in this study.

A study in South Korea asked people to eat about 70g a day of chungkookjang (fermented soybean). There were improvements in some measures of obesity, including percentage body fat, lean body mass, waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference in women. However there were no changes in weight for men or women.

A systematic review of all studies that looked at the impact of fermented foods on satiety (feeling full) showed no effect.

What should I do?

The evidence so far is very weak to support or recommend fermented foods for weight loss. These experimental studies have been short in length, and many did not report weight changes.

To date, most of the studies have used different fermented foods, so it is difficult to generalise across them all.

Nevertheless, fermented foods are still useful as part of a healthy, varied and balanced diet, particularly if you enjoy them. They are rich in healthy bacteria, and nutrients.

Are there downsides?

Some fermented foods, such as kimchi and sauerkraut, have added salt. The latest kimchi study said the average amount of kimchi South Koreans eat provides about 490mg of salt a day. For an Australian, this would represent about 50% of the suggested dietary target for optimal health.

Eating too much salt increases your risk of high blood pressure, heart disease and stroke.

Evangeline Mantzioris, Program Director of Nutrition and Food Sciences, Accredited Practising Dietitian, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How to Think More Effectively – by Alain de Botton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our brain is our most powerful organ, and our mind is an astonishing thing. So why do we sometimes go off-piste?

The School of Life‘s Alain de Botton lays out for us a framework of cumulative thinking, directions for effort, and unlikely tools for cognitive improvement.

The book especially highlights the importance of such things as…

- making time for cumulative thinking

- not, however, trying to force it

- working with, rather than in spite of, distractions

- noting and making use of our irrationalities

- taking what we think/do both seriously and lightly, at once

- practising constructive self-doubt

The style is as clear and easy as you may have come to expect from Alain de Botton / The School of Life, and yet, its ideas are still likely to challenge every reader in some (good!) way.

Bottom line: if you would like what you think, say, do to be more meaningful, this book will help you to make the most of your abilities!

Click here to check out How To Think More Effectively, and upgrade your thought processes!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: