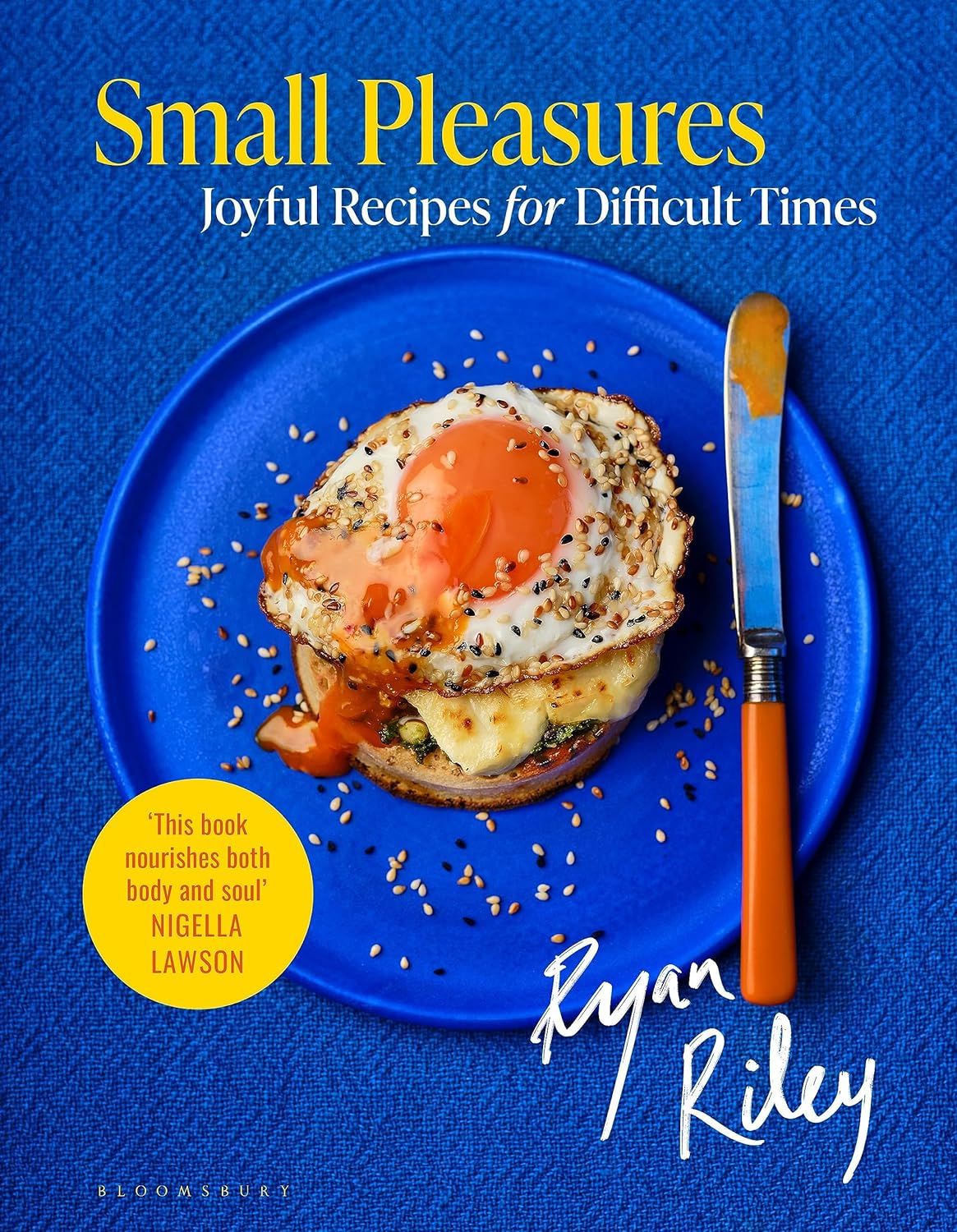

Small Pleasures – by Ryan Riley

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When Hippocrates said “let food be thy medicine, and let medicine be thy food”, he may or may not have had this book in mind.

In terms of healthiness, this one’s not the very most nutritionist-approved recipe book we’ve ever reviewed. It’s not bad, to be clear!

But the physical health aspect is secondary to the mental health aspects, in this one, as you’ll see. And as we say, “mental health is also just health”.

The book is divided into three sections:

- Comfort—for when you feel at your worst, for when eating is a chore, for when something familiar and reassuring will bring you solace. Here we find flavor and simplicity; pastas, eggs, stews, potato dishes, and the like.

- Restoration—for when your energy needs reawakening. Here we find flavors fresh and tangy, enlivening and bright. Things to make you feel alive.

- Pleasure—while there’s little in the way of health-food here, the author describes the dishes in this section as “a love letter to yourself; they tell you that you’re special as you ready yourself to return to the world”.

And sometimes, just sometimes, we probably all need a little of that.

Bottom line: if you’d like to bring a little more joie de vivre to your cuisine, this book can do that.

Click here to check out Small Pleasures, and rekindle joy in your kitchen!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

The Whole-Body Approach to Osteoporosis – by Keith McCormick

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You probably already know to get enough calcium and vitamin D, and do some resistance training. What does this book offer beyond that advice?

It’s pretty comprehensive, as it turns out. It covers the above, plus the wide range of medications available, what supplements help or harm or just don’t have enough evidence either way yet, things like that.

Amongst the most important offerings are the signs and symptoms that can help monitor your bone health (things you can do at home! Like examinations of your fingernails, hair, skin, tongue, and so forth, that will reveal information about your internal biochemical make-up), as well as what lab tests to ask for. Which is important, as osteoporosis is one of those things whereby we often don’t learn something is wrong until it’s too late.

The author is a chiropractor, which doesn’t always have a reputation as the most robustly science-based of physical therapy options, but he…

- doesn’t talk about chiropractic

- did confer with a flock of experts (osteopaths, nutritionists, etc) to inform/check his work

- does refer consistently to good science, and explains it well

- includes 16 pages of academic references, and yes, they are very reputable publications

Bottom line: this one really does give what the subtitle promises: a whole body approach to avoiding (or reversing) osteoporosis.

Click here to check out The Whole Body Approach To Osteoporosis; sooner is better than later!

Share This Post

What To Eat, Take, And Do Before A Workout

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What to eat, take, and do before a workout

We’ve previously written about how to recover quickly after a workout:

Overdone It? How To Speed Up Recovery After Exercise

Today we’ll look at the flipside: how to prepare for exercise.

Pre-workout nutrition

As per what we wrote (and referenced) above, a good dictum is “protein whenever; carbs after”. See also:

Pre- versus post-exercise protein intake has similar effects on muscular adaptations

It’s recommended to have a light, balanced meal a few hours before exercising, though there are nuances:

International society of sports nutrition position stand: nutrient timing

Hydration

You will not perform well unless you are well-hydrated:

Influence of Dehydration on Intermittent Sprint Performance

However, you also don’t want to just be sloshing around when exercising because you took care to get in your two litres before hitting the gym.

For this reason, quality can be more important than quantity, and sodium and other electrolytes can be important and useful, but will not be so for everyone in all circumstances.

Here’s what we wrote previously about that:

Are Electrolyte Supplements Worth It?

Pre-workout supplements

We previously wrote about the use of creatine specifically:

Creatine: Very Different For Young & Old People

Caffeine is also a surprisingly effective pre-workout supplement:

International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance

Depending on the rate at which you metabolize caffeine (there are genes for this), the effects will come/go earlier/later, but as a general rule of thumb, caffeine should work within about 20 minutes, and will peak in effect 1–2 hours after consumption:

Nutrition Supplements to Stimulate Lipolysis: A Review in Relation to Endurance Exercise Capacity

Branched Chain Amino Acids, or BCAAs, are commonly enjoyed as pre-workout supplement to help reduce creatine kinase and muscle soreness, but won’t accelerate recovery:

…but will help boost muscle-growth (or maintenance, depending on your exercise and diet) in the long run:

Where can I get those?

We don’t sell them, but here’s an example product on Amazon, for your convenience

There are also many multi-nutrient pre-workout supplements on the market (like the secondary product offered with the BCAA above). We’d need a lot more room to go into all of those (maybe we’ll include some in our Monday Research Review editions), but meanwhile, here’s some further reading:

The 11 Best Pre-Workout Supplements According to a Dietitian

(it’s more of a “we ranked these commercial products” article than a science article, but it’s a good starting place for understanding about what’s on offer)

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Ricezempic: is there any evidence this TikTok trend will help you lose weight?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you spend any time looking at diet and lifestyle content on social media, you may well have encountered a variety of weight loss “hacks”.

One of the more recent trends is a home-made drink called ricezempic, made by soaking uncooked rice and then straining it to drink the leftover starchy water. Sounds delicious, right?

Its proponents claim it leads to weight loss by making you feel fuller for longer and suppressing your appetite, working in a similar way to the sought-after drug Ozempic – hence the name.

So does this drink actually mimic the weight loss effects of Ozempic? Spoiler alert – probably not. But let’s look at what the evidence tells us.

New Africa/Shutterstock How do you make ricezempic?

While the recipe can vary slightly depending on who you ask, the most common steps to make ricezempic are:

- soak half a cup of white rice (unrinsed) in one cup of warm or hot water up to overnight

- drain the rice mixture into a fresh glass using a strainer

- discard the rice (but keep the starchy water)

- add the juice of half a lime or lemon to the starchy water and drink.

TikTokers advise that best results will happen if you drink this concoction once a day, first thing in the morning, before eating.

The idea is that the longer you consume ricezempic for, the more weight you’ll lose. Some claim introducing the drink into your diet can lead to a weight loss of up to 27 kilograms in two months.

Resistant starch

Those touting ricezempic argue it leads to weight loss because of the resistant starch rice contains. Resistant starch is a type of dietary fibre (also classified as a prebiotic). There’s no strong evidence it makes you feel fuller for longer, but it does have proven health benefits.

Studies have shown consuming resistant starch may help regulate blood sugar, aid weight loss and improve gut health.

Research has also shown eating resistant starch reduces the risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease and other chronic diseases.

Ricezempic is made by soaking rice in water. Kristi Blokhin/Shutterstock Resistant starch is found in many foods. These include beans, lentils, wholegrains (oats, barley, and rice – particularly brown rice), bananas (especially when they’re under-ripe or green), potatoes, and nuts and seeds (particularly chia seeds, flaxseeds and almonds).

Half a cup of uncooked white rice (as per the ricezempic recipe) contains around 0.6 grams of resistant starch. For optimal health benefits, a daily intake of 15–20 grams of resistant starch is recommended. Although there is no concrete evidence on the amount of resistant starch that leaches from rice into water, it’s likely to be significantly less than 0.6 grams as the whole rice grain is not being consumed.

Ricezempic vs Ozempic

Ozempic was originally developed to help people with diabetes manage their blood sugar levels but is now commonly used for weight loss.

Ozempic, along with similar medications such as Wegovy and Trulicity, is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. These drugs mimic the GLP-1 hormone the body naturally produces. By doing so, they slow down the digestive process, which helps people feel fuller for longer, and curbs their appetite.

While the resistant starch in rice could induce some similar benefits to Ozempic (such as feeling full and therefore reducing energy intake), no scientific studies have trialled ricezempic using the recipes promoted on social media.

Ozempic has a long half-life, remaining active in the body for about seven days. In contrast, consuming one cup of rice provides a feeling of fullness for only a few hours. And simply soaking rice in water and drinking the starchy water will not provide the same level of satiety as eating the rice itself.

Other ways to get resistant starch in your diet

There are several ways to consume more resistant starch while also gaining additional nutrients and vitamins compared to what you get from ricezempic.

1. Cooked and cooled rice

Letting cooked rice cool over time increases its resistant starch content. Reheating the rice does not significantly reduce the amount of resistant starch that forms during cooling. Brown rice is preferable to white rice due to its higher fibre content and additional micronutrients such as phosphorus and magnesium.

2. More legumes

These are high in resistant starch and have been shown to promote weight management when eaten regularly. Why not try a recipe that has pinto beans, chickpeas, black beans or peas for dinner tonight?

3. Cooked and cooled potatoes

Cooking potatoes and allowing them to cool for at least a few hours increases their resistant starch content. Fully cooled potatoes are a rich source of resistant starch and also provide essential nutrients like potassium and vitamin C. Making a potato salad as a side dish is a great way to get these benefits.

In a nutshell

Although many people on social media have reported benefits, there’s no scientific evidence drinking rice water or “ricezempic” is effective for weight loss. You probably won’t see any significant changes in your weight by drinking ricezempic and making no other adjustments to your diet or lifestyle.

While the drink may provide a small amount of resistant starch residue from the rice, and some hydration from the water, consuming foods that contain resistant starch in their full form would offer significantly more nutritional benefits.

More broadly, be wary of the weight loss hacks you see on social media. Achieving lasting weight loss boils down to gradually adopting healthy eating habits and regular exercise, ensuring these changes become lifelong habits.

Emily Burch, Accredited Practising Dietitian and Lecturer, Southern Cross University and Lauren Ball, Professor of Community Health and Wellbeing, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

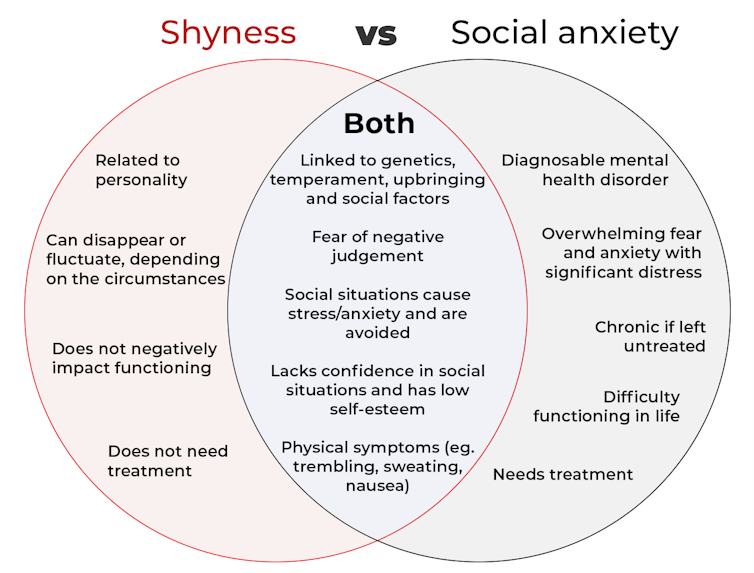

What’s the difference between shyness and social anxiety?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

The terms “shyness” and “social anxiety” are often used interchangeably because they both involve feeling uncomfortable in social situations.

However, feeling shy, or having a shy personality, is not the same as experiencing social anxiety (short for “social anxiety disorder”).

Here are some of the similarities and differences, and what the distinction means.

pathdoc/Shutterstock How are they similar?

It can be normal to feel nervous or even stressed in new social situations or when interacting with new people. And everyone differs in how comfortable they feel when interacting with others.

For people who are shy or socially anxious, social situations can be very uncomfortable, stressful or even threatening. There can be a strong desire to avoid these situations.

People who are shy or socially anxious may respond with “flight” (by withdrawing from the situation or avoiding it entirely), “freeze” (by detaching themselves or feeling disconnected from their body), or “fawn” (by trying to appease or placate others).

A complex interaction of biological and environmental factors is also thought to influence the development of shyness and social anxiety.

For example, both shy children and adults with social anxiety have neural circuits that respond strongly to stressful social situations, such as being excluded or left out.

People who are shy or socially anxious commonly report physical symptoms of stress in certain situations, or even when anticipating them. These include sweating, blushing, trembling, an increased heart rate or hyperventilation.

How are they different?

Social anxiety is a diagnosable mental health condition and is an example of an anxiety disorder.

For people who struggle with social anxiety, social situations – including social interactions, being observed and performing in front of others – trigger intense fear or anxiety about being judged, criticised or rejected.

To be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, social anxiety needs to be persistent (lasting more than six months) and have a significant negative impact on important areas of life such as work, school, relationships, and identity or sense of self.

Many adults with social anxiety report feeling shy, timid and lacking in confidence when they were a child. However, not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. Also, feeling shy does not necessarily mean a person meets the criteria for social anxiety disorder.

People vary in how shy or outgoing they are, depending on where they are, who they are with and how comfortable they feel in the situation. This is particularly true for children, who sometimes appear reserved and shy with strangers and peers, and outgoing with known and trusted adults.

Individual differences in temperament, personality traits, early childhood experiences, family upbringing and environment, and parenting style, can also influence the extent to which people feel shy across social situations.

Not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. 249 Anurak/Shutterstock However, people with social anxiety have overwhelming fears about embarrassing themselves or being negatively judged by others; they experience these fears consistently and across multiple social situations.

The intensity of this fear or anxiety often leads people to avoid situations. If avoiding a situation is not possible, they may engage in safety behaviours, such as looking at their phone, wearing sunglasses or rehearsing conversation topics.

The effect social anxiety can have on a person’s life can be far-reaching. It may include low self-esteem, breakdown of friendships or romantic relationships, difficulties pursuing and progressing in a career, and dropping out of study.

The impact this has on a person’s ability to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life, and the distress this causes, differentiates social anxiety from shyness.

Children can show similar signs or symptoms of social anxiety to adults. But they may also feel upset and teary, irritable, have temper tantrums, cling to their parents, or refuse to speak in certain situations.

If left untreated, social anxiety can set children and young people up for a future of missed opportunities, so early intervention is key. With professional and parental support, patience and guidance, children can be taught strategies to overcome social anxiety.

Why does the distinction matter?

Social anxiety disorder is a mental health condition that persists for people who do not receive adequate support or treatment.

Without treatment, it can lead to difficulties in education and at work, and in developing meaningful relationships.

Receiving a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder can be validating for some people as it recognises the level of distress and that its impact is more intense than shyness.

A diagnosis can also be an important first step in accessing appropriate, evidence-based treatment.

Different people have different support needs. However, clinical practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioural therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that teaches people practical coping skills). This is often used with exposure therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that helps people face their fears by breaking them down into a series of step-by-step activities). This combination is effective in-person, online and in brief treatments.

Treatment is available online as well as in-person. ImYanis/Shutterstock For more support or further reading

Online resources about social anxiety include:

- This Way Up’s online program for managing excessive shyness and fear of social situations

- Beyond Blue’s resources on social anxiety

- a guide to looking after yourself if you have social anxiety, from the Western Australian health department

- social anxiety online program for children and teens from the University of Queensland

- inroads, a self-guided online program for young adults who drink alcohol to manage their anxiety.

We thank the Black Dog Institute Lived Experience Advisory Network members for providing feedback and input for this article and our research.

Kayla Steele, Postdoctoral research fellow and clinical psychologist, UNSW Sydney and Jill Newby, Professor, NHMRC Emerging Leader & Clinical Psychologist, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Clean Needles Save Lives. In Some States, They Might Not Be Legal.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Kim Botteicher hardly thinks of herself as a criminal.

On the main floor of a former Catholic church in Bolivar, Pennsylvania, Botteicher runs a flower shop and cafe.

In the former church’s basement, she also operates a nonprofit organization focused on helping people caught up in the drug epidemic get back on their feet.

The nonprofit, FAVOR ~ Western PA, sits in a rural pocket of the Allegheny Mountains east of Pittsburgh. Her organization’s home county of Westmoreland has seen roughly 100 or more drug overdose deaths each year for the past several years, the majority involving fentanyl.

Thousands more residents in the region have been touched by the scourge of addiction, which is where Botteicher comes in.

She helps people find housing, jobs, and health care, and works with families by running support groups and explaining that substance use disorder is a disease, not a moral failing.

But she has also talked publicly about how she has made sterile syringes available to people who use drugs.

“When that person comes in the door,” she said, “if they are covered with abscesses because they have been using needles that are dirty, or they’ve been sharing needles — maybe they’ve got hep C — we see that as, ‘OK, this is our first step.’”

Studies have identified public health benefits associated with syringe exchange services. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says these programs reduce HIV and hepatitis C infections, and that new users of the programs are more likely to enter drug treatment and more likely to stop using drugs than nonparticipants.

This harm-reduction strategy is supported by leading health groups, such as the American Medical Association, the World Health Organization, and the International AIDS Society.

But providing clean syringes could put Botteicher in legal danger. Under Pennsylvania law, it’s a misdemeanor to distribute drug paraphernalia. The state’s definition includes hypodermic syringes, needles, and other objects used for injecting banned drugs. Pennsylvania is one of 12 states that do not implicitly or explicitly authorize syringe services programs through statute or regulation, according to a 2023 analysis. A few of those states, but not Pennsylvania, either don’t have a state drug paraphernalia law or don’t include syringes in it.

Those working on the front lines of the opioid epidemic, like Botteicher, say a reexamination of Pennsylvania’s law is long overdue.

There’s an urgency to the issue as well: Billions of dollars have begun flowing into Pennsylvania and other states from legal settlements with companies over their role in the opioid epidemic, and syringe services are among the eligible interventions that could be supported by that money.

The opioid settlements reached between drug companies and distributors and a coalition of state attorneys general included a list of recommendations for spending the money. Expanding syringe services is listed as one of the core strategies.

But in Pennsylvania, where 5,158 people died from a drug overdose in 2022, the state’s drug paraphernalia law stands in the way.

Concerns over Botteicher’s work with syringe services recently led Westmoreland County officials to cancel an allocation of $150,000 in opioid settlement funds they had previously approved for her organization. County Commissioner Douglas Chew defended the decision by saying the county “is very risk averse.”

Botteicher said her organization had planned to use the money to hire additional recovery specialists, not on syringes. Supporters of syringe services point to the cancellation of funding as evidence of the need to change state law, especially given the recommendations of settlement documents.

“It’s just a huge inconsistency,” said Zoe Soslow, who leads overdose prevention work in Pennsylvania for the public health organization Vital Strategies. “It’s causing a lot of confusion.”

Though sterile syringes can be purchased from pharmacies without a prescription, handing out free ones to make drug use safer is generally considered illegal — or at least in a legal gray area — in most of the state. In Pennsylvania’s two largest cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, officials have used local health powers to provide legal protection to people who operate syringe services programs.

Even so, in Philadelphia, Mayor Cherelle Parker, who took office in January, has made it clear she opposes using opioid settlement money, or any city funds, to pay for the distribution of clean needles, The Philadelphia Inquirer has reported. Parker’s position signals a major shift in that city’s approach to the opioid epidemic.

On the other side of the state, opioid settlement funds have had a big effect for Prevention Point Pittsburgh, a harm reduction organization. Allegheny County reported spending or committing $325,000 in settlement money as of the end of last year to support the organization’s work with sterile syringes and other supplies for safer drug use.

“It was absolutely incredible to not have to fundraise every single dollar for the supplies that go out,” said Prevention Point’s executive director, Aaron Arnold. “It takes a lot of energy. It pulls away from actual delivery of services when you’re constantly having to find out, ‘Do we have enough money to even purchase the supplies that we want to distribute?’”

In parts of Pennsylvania that lack these legal protections, people sometimes operate underground syringe programs.

The Pennsylvania law banning drug paraphernalia was never intended to apply to syringe services, according to Scott Burris, director of the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University. But there have not been court cases in Pennsylvania to clarify the issue, and the failure of the legislature to act creates a chilling effect, he said.

Carla Sofronski, executive director of the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Network, said she was not aware of anyone having faced criminal charges for operating syringe services in the state, but she noted the threat hangs over people who do and that they are taking a “great risk.”

In 2016, the CDC flagged three Pennsylvania counties — Cambria, Crawford, and Luzerne — among 220 counties nationwide in an assessment of communities potentially vulnerable to the rapid spread of HIV and to new or continuing high rates of hepatitis C infections among people who inject drugs.

Kate Favata, a resident of Luzerne County, said she started using heroin in her late teens and wouldn’t be alive today if it weren’t for the support and community she found at a syringe services program in Philadelphia.

“It kind of just made me feel like I was in a safe space. And I don’t really know if there was like a come-to-God moment or come-to-Jesus moment,” she said. “I just wanted better.”

Favata is now in long-term recovery and works for a medication-assisted treatment program.

At clinics in Cambria and Somerset Counties, Highlands Health provides free or low-cost medical care. Despite the legal risk, the organization has operated a syringe program for several years, while also testing patients for infectious diseases, distributing overdose reversal medication, and offering recovery options.

Rosalie Danchanko, Highlands Health’s executive director, said she hopes opioid settlement money can eventually support her organization.

“Why shouldn’t that wealth be spread around for all organizations that are working with people affected by the opioid problem?” she asked.

In February, legislation to legalize syringe services in Pennsylvania was approved by a committee and has moved forward. The administration of Gov. Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, supports the legislation. But it faces an uncertain future in the full legislature, in which Democrats have a narrow majority in the House and Republicans control the Senate.

One of the bill’s lead sponsors, state Rep. Jim Struzzi, hasn’t always supported syringe services. But the Republican from western Pennsylvania said that since his brother died from a drug overdose in 2014, he has come to better understand the nature of addiction.

In the committee vote, nearly all of Struzzi’s Republican colleagues opposed the bill. State Rep. Paul Schemel said authorizing the “very instrumentality of abuse” crossed a line for him and “would be enabling an evil.”

After the vote, Struzzi said he wanted to build more bipartisan support. He noted that some of his own skepticism about the programs eased only after he visited Prevention Point Pittsburgh and saw how workers do more than just hand out syringes. These types of programs connect people to resources — overdose reversal medication, wound care, substance use treatment — that can save lives and lead to recovery.

“A lot of these people are … desperate. They’re alone. They’re afraid. And these programs bring them into someone who cares,” Struzzi said. “And that, to me, is a step in the right direction.”

At her nonprofit in western Pennsylvania, Botteicher is hoping lawmakers take action.

“If it’s something that’s going to help someone, then why is it illegal?” she said. “It just doesn’t make any sense to me.”

This story was co-reported by WESA Public Radio and Spotlight PA, an independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit newsroom producing investigative and public-service journalism that holds power to account and drives positive change in Pennsylvania.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

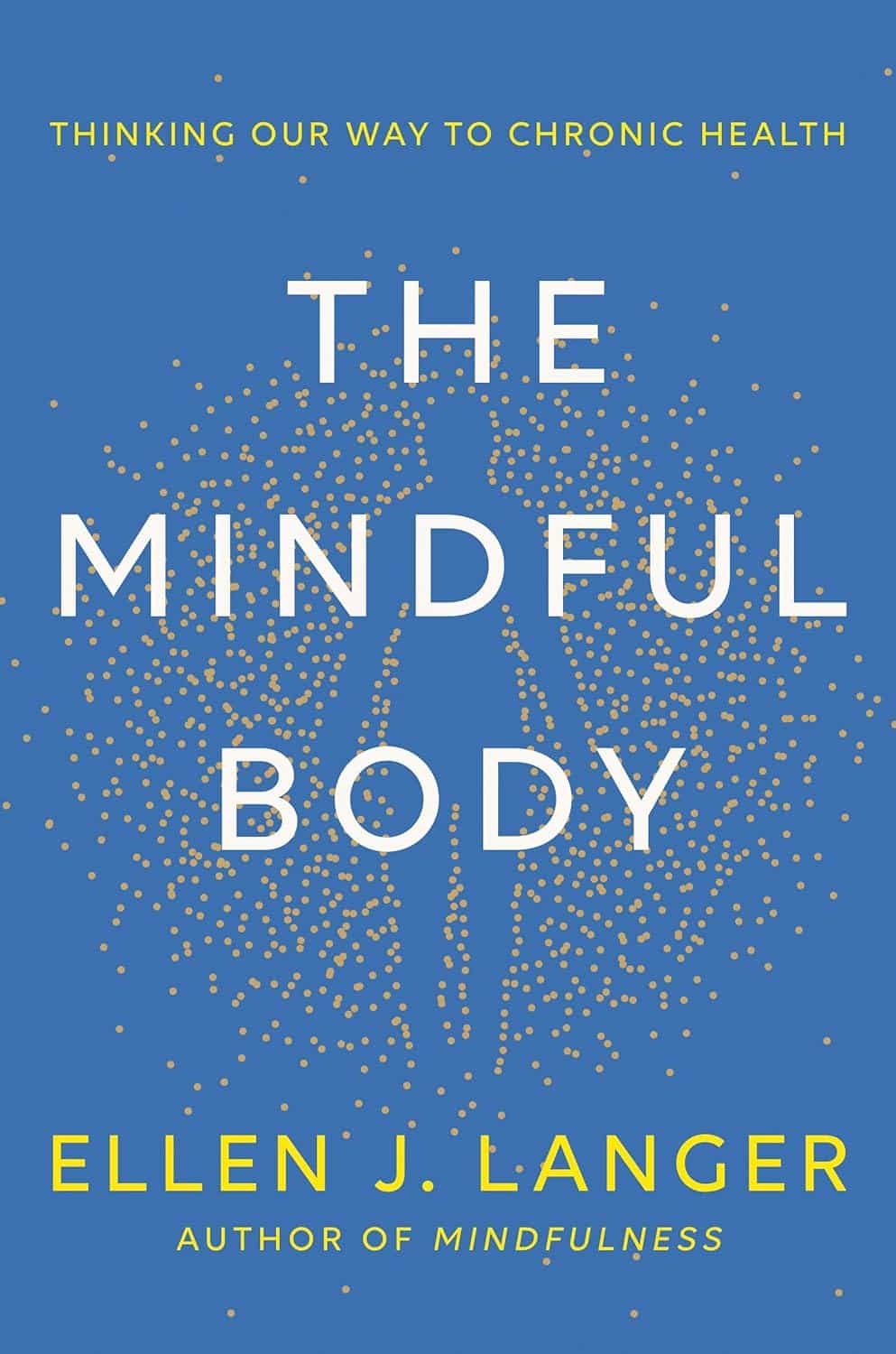

The Mindful Body – by Dr. Ellen Langer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Fear not, this is not a “think healing thoughts” New Age sort of book. In fact, it’s quite the contrary.

The most common negative reviews for this on Amazon are that it is too densely packed with scientific studies, and some readers found it hard to get through since they didn’t find it “light reading”.

Counterpoint: this reviewer found it very readable. A lot of it is as accessible as 10almonds content, and a lot is perhaps halfway between 10almonds content in readability, and the studies we cite. So if you’re at least somewhat comfortable reading academic literature, you should be fine.

The author, a professor of psychology (tenured at Harvard since 1981), examines a lot of psychosomatic effect. Psychosomatic effect is often dismissed as “it’s all in your head”, but it means: what’s in your head has an effect on your body, because your brain talks to the rest of the body and directs bodily responses and actions/reactions.

An obvious presentation of this in medicine is the placebo/nocebo effect, but Dr. Langer’s studies (indeed, many of the studies she cites are her own, from over the course of her 40-year career) take it further and deeper, including her famous “Counterclockwise” study in which many physiological markers of aging were changed (made younger) by changing the environment that people spent time in, to resemble their youth, and giving them instructions to act accordingly while there.

In the category of subjective criticism: the book is not exceptionally well-organized, but if you read for example a chapter a day, you’ll get all the ideas just fine.

Bottom line: if you want a straightforward hand-holding “how-to” guide, this isn’t it. But it is very much information-packed with a lot of ideas and high-quality science that’s easily applicable to any of us.

Click here to check out The Mindful Body, and indeed grow your chronic good health!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: