Acid Reflux Diet Cookbook – by Dr. Harmony Reynolds

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Notwithstanding the title, this is far more than just a recipe book. Of course, it is common for health-focused recipe books to begin with a preamble about the science that’s going to be applied, but in this case, the science makes up a larger portion of the book than usual, along with practical tips about how to best implement certain things, at home and when out and about.

Dr. Reynolds also gives a lot of information about such things as medications that could be having an effect one way or the other, and even other lifestyle factors such as exercise and so forth, and yes, even stress management. Because for many people, what starts as acid reflux can soon become ulcers, and that’s not good.

The recipes themselves are diverse and fairly simple; they’re written solely with acid reflux in mind and not other health considerations, but they are mostly heathy in the generalized sense too.

The style is straight to the point with zero padding sensationalism, or chit-chat. It can make for a slightly dry read, but let’s face it, nobody is buying this book for its entertainment value.

Bottom line: if you have been troubled by acid reflux, this book will help you to eat your way safely out of it.

Click here to check out the Acid Reflux Diet Cookbook, and enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Pomegranate’s Health Gifts Are Mostly In Its Peel

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Pomegranate Peel’s Potent Potential

Pomegranates have been enjoying a new surge in popularity in some parts, widely touted for their health benefits. What’s not so widely touted is that most of the bioactive compounds that give these benefits are concentrated in the peel, which most people in most places throw away.

They do exist in the fruit too! But if you’re discarding the peel, you’re missing out:

Food Applications and Potential Health Benefits of Pomegranate and its Derivatives

“That peel is difficult and not fun to eat though”

Indeed. Drying the peel, especially freeze-drying it, is a good first step:

❝Freeze drying peels had a positive effect on the total phenolic, tannins and flavonoid than oven drying at all temperature range. Moreover, freeze drying had a positive impact on the +catechin, -epicatechin, hesperidin and rutin concentrations of fruit peel. ❞

Once it is freeze-dried, it is easy to grind it into a powder for use as a nutritional supplement.

“How useful is it?”

Studies with 500mg and 1000mg per day in people with cases of obesity and/or type 2 diabetes saw significant improvements in assorted biomarkers of cardiometabolic health, including blood pressure, blood sugar levels, cholesterol, and hemoglobin A1C:

- Effects of pomegranate extract supplementation on inflammation in overweight and obese individuals: A randomized controlled clinical trial

- Beneficial effects of pomegranate peel extract on plasma lipid profile, fatty acids levels and blood pressure in patients with diabetes mellitus type-2: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

It also has anticancer properties:

- Punicalagin, a polyphenol from pomegranate fruit, induces growth inhibition and apoptosis in human PC-3 and LNCaP cells

- Punica granatum (Pomegranate) activity in health promotion and cancer prevention

- The extract from Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel induces apoptosis and impairs metastasis in prostate cancer cells

…and neuroprotective benefits:

- Long-term (15 mo) dietary supplementation with pomegranates attenuates cognitive and behavioral deficits

- Neuroprotective Effects of Pomegranate Peel Extract

- An Evaluation of the Effects of a Non-caffeinated Energy Dietary Supplement on Cognitive and Physical Performance

…and it may protect against osteopenia and osteoporosis, but we only have animal or in vitro studies so far, for example:

- Pomegranate Peel Extract Prevents Bone Loss in a Preclinical Model of Osteoporosis and Stimulates Osteoblastic Differentiation in Vitro

- Pomegranate and its derivatives can improve bone health through decreased inflammation and oxidative stress in an animal model of postmenopausal osteoporosis

Want to try it?

We don’t sell it, but you can buy pomegranates at your local supermarket, or buy the peel extract ready-made from online sources; here’s an example on Amazon for your convenience

(the marketing there is for use of the 100% pomegranate peel powder as a face mask; it also has health benefits for the skin when applied topically, but we didn’t have time to cover that today)

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

New Eye Drops vs Age-Related Macular Degeneration

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written previously on preventative interventions against age-related macular degeneration (AMD):

How To Avoid Age-Related Macular Degeneration

…and then supplemented that, to to speak, with:

Fatty Acids For The Eyes & Brain: The Good And The Bad

However, what if ADM happens anyway?

Not a dry eye in the house

Age-related macular degeneration comes in two forms, wet and dry, of which, dry is by far the most common (being 9 out of 10 of all cases of AMD).

It sounds like the sort of thing that eye drops should be in order for, but in fact, the wetness vs dryness is about what’s going on inside the macula, not what’s happening on the surface of the eye. Up until now, the only treatments available (aside from supplement regimes, which we linked just above) have been injectable drugs, which:

- are not fun (yes, the injection goes into the eyeball)

- don’t actually work very well (modest improvements in vision; significantly better than nothing though)

…and even those won’t help in the late stages.

However, a Korean research team has developed eye drops with peptides that inhibit the interactions between Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and TLR-signalling proteins, in a way that addresses part of the pathogenesis of AMD:

That’s quite a dense read though, so here’s a pop-science article that explains it more simply, but in more detail than we can here:

New eye drop treatment offers hope for dry AMD patients

This is a big improvement from the state of affairs previously, in which eye drops really couldn’t help at all:

What eye drops can treat macular degeneration? ← pop-science article from January 2023

No AMD, and/but want your eye health to be better?

Check out these:

10 Great Exercises to Improve Your Eyesight ← you can quickly see the results for yourself

Take care!

Share This Post

-

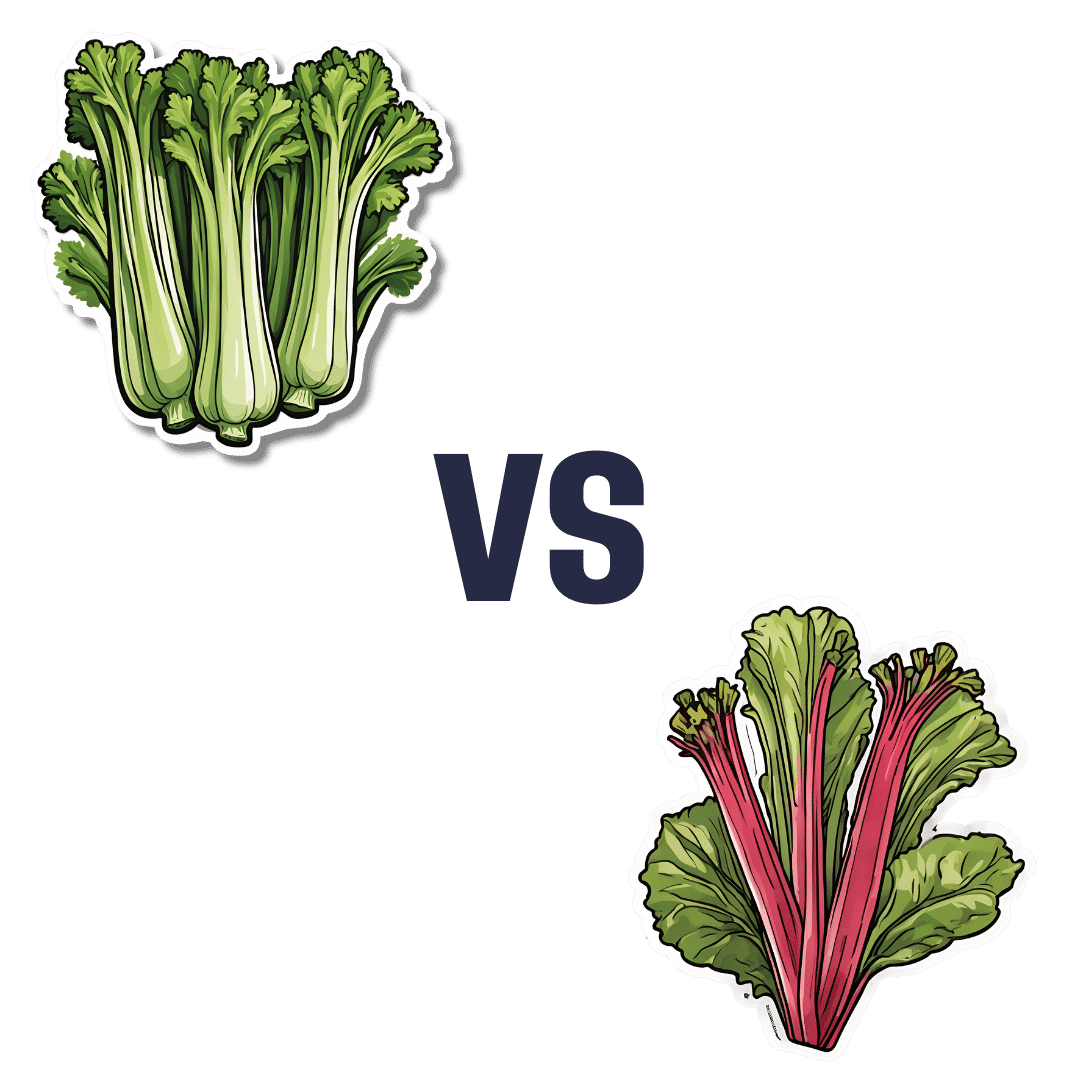

Celery vs Rhubarb – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing celery to rhubarb, we picked the rhubarb.

Why?

In terms of macros, rhubarb has more carbs and fiber, the ratio of which give it the lower glycemic index, though both are low glycemic index foods. This means this category is a very marginal win for rhubarb.

When it comes to vitamins, rhubarb has more vitamin C, while celery has more of vitamins A, B5, B6, and B9. A win for celery, this time.

In the category of minerals, rhubarb has more calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, potassium, and selenium, while celery has more copper and phosphorus. This one’s a win for rhubarb.

Let’s give a quick nod also to polyphenols; rhubarb has more by overall quantity, and more in terms of “more useful to humans” too, being rich in an assortment of flavanols while celery must make do with some furanocoumarins.

In short, enjoy either or both, but nutritional density is a great reason to get some rhubarb in!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Lies I Taught in Medical School – by Dr. Robert Lufkin

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There seems to be a pattern of doctors who practice medicine one way, get a serious disease personally, and then completely change their practice of medicine afterwards. This is one of those cases.

Dr. Lufkin here presents, on a chapter-by-chapter basis, the titularly promised “lies” or, in more legally compliant speak (as he acknowledges in his preface), flawed hypotheses that are generally taught as truths. In many cases, the “lie” is some manner of “xyz is normal and nothing to worry about”, and/or “there is nothing to be done about xyz; suck it up”.

The end result of the information is not complicated—enjoy a plants-forward whole foods low-carb diet to avoid metabolic diseases and all the other things to branch off from same (Dr. Lufkin makes a fair case for metabolic disease leading to a lot of secondary diseases that aren’t considered metabolic diseases per se). But, the journey there is actually important, as it answers a lot of questions that are much less commonly understood, and often not even especially talked-about, despite their great import and how they may affect health decisions beyond the dietary. Things like understanding the downsides of statins, or the statistical models that can be used to skew studies, per relative risk reduction and so forth.

Bottom line: this book gives the ins and outs of what can go right or wrong with metabolic health and why, and how to make sure you don’t sabotage your health through missing information.

Click here to check out Lies I Taught In Medical School, and arm yourself with knowledge!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why rating your pain out of 10 is tricky

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“It’s really sore,” my (Josh’s) five-year-old daughter said, cradling her broken arm in the emergency department.

“But on a scale of zero to ten, how do you rate your pain?” asked the nurse.

My daughter’s tear-streaked face creased with confusion.

“What does ten mean?”

“Ten is the worst pain you can imagine.” She looked even more puzzled.

As both a parent and a pain scientist, I witnessed firsthand how our seemingly simple, well-intentioned pain rating systems can fall flat.

altanaka/Shutterstock What are pain scales for?

The most common scale has been around for 50 years. It asks people to rate their pain from zero (no pain) to ten (typically “the worst pain imaginable”).

This focuses on just one aspect of pain – its intensity – to try and rapidly understand the patient’s whole experience.

How much does it hurt? Is it getting worse? Is treatment making it better?

Rating scales can be useful for tracking pain intensity over time. If pain goes from eight to four, that probably means you’re feeling better – even if someone else’s four is different to yours.

Research suggests a two-point (or 30%) reduction in chronic pain severity usually reflects a change that makes a difference in day-to-day life.

But that common upper anchor in rating scales – “worst pain imaginable” – is a problem.

People usually refer to their previous experiences when rating pain. sasirin pamai/Shutterstock A narrow tool for a complex experience

Consider my daughter’s dilemma. How can anyone imagine the worst possible pain? Does everyone imagine the same thing? Research suggests they don’t. Even kids think very individually about that word “pain”.

People typically – and understandably – anchor their pain ratings to their own life experiences.

This creates dramatic variation. For example, a patient who has never had a serious injury may be more willing to give high ratings than one who has previously had severe burns.

“No pain” can also be problematic. A patient whose pain has receded but who remains uncomfortable may feel stuck: there’s no number on the zero-to-ten scale that can capture their physical experience.

Increasingly, pain scientists recognise a simple number cannot capture the complex, highly individual and multifaceted experience that is pain.

Who we are affects our pain

In reality, pain ratings are influenced by how much pain interferes with a person’s daily activities, how upsetting they find it, their mood, fatigue and how it compares to their usual pain.

Other factors also play a role, including a patient’s age, sex, cultural and language background, literacy and numeracy skills and neurodivergence.

For example, if a clinician and patient speak different languages, there may be extra challenges communicating about pain and care.

Some neurodivergent people may interpret language more literally or process sensory information differently to others. Interpreting what people communicate about pain requires a more individualised approach.

Impossible ratings

Still, we work with the tools available. There is evidence people do use the zero-to-ten pain scale to try and communicate much more than only pain’s “intensity”.

So when a patient says “it’s eleven out of ten”, this “impossible” rating is likely communicating more than severity.

They may be wondering, “Does she believe me? What number will get me help?” A lot of information is crammed into that single number. This patient is most likely saying, “This is serious – please help me.”

In everyday life, we use a range of other communication strategies. We might grimace, groan, move less or differently, use richly descriptive words or metaphors.

Collecting and evaluating this kind of complex and subjective information about pain may not always be feasible, as it is hard to standardise.

As a result, many pain scientists continue to rely heavily on rating scales because they are simple, efficient and have been shown to be reliable and valid in relatively controlled situations.

But clinicians can also use this other, more subjective information to build a fuller picture of the person’s pain.

How can we communicate better about pain?

There are strategies to address language or cultural differences in how people express pain.

Visual scales are one tool. For example, the “Faces Pain Scale-Revised” asks patients to choose a facial expression to communicate their pain. This can be particularly useful for children or people who aren’t comfortable with numeracy and literacy, either at all, or in the language used in the health-care setting.

A vertical “visual analogue scale” asks the person to mark their pain on a vertical line, a bit like imagining “filling up” with pain.

Modified visual scales are sometimes used to try to overcome communication challenges. Nenadmil/Shutterstock What can we do?

Health professionals

Take time to explain the pain scale consistently, remembering that the way you phrase the anchors matters.

Listen for the story behind the number, because the same number means different things to different people.

Use the rating as a launchpad for a more personalised conversation. Consider cultural and individual differences. Ask for descriptive words. Confirm your interpretation with the patient, to make sure you’re both on the same page.

Patients

To better describe pain, use the number scale, but add context.

Try describing the quality of your pain (burning? throbbing? stabbing?) and compare it to previous experiences.

Explain the impact the pain is having on you – both emotionally and how it affects your daily activities.

Parents

Ask the clinician to use a child-suitable pain scale. There are special tools developed for different ages such as the “Faces Pain Scale-Revised”.

Paediatric health professionals are trained to use age-appropriate vocabulary, because children develop their understanding of numbers and pain differently as they grow.

A starting point

In reality, scales will never be perfect measures of pain. Let’s see them as conversation starters to help people communicate about a deeply personal experience.

That’s what my daughter did — she found her own way to describe her pain: “It feels like when I fell off the monkey bars, but in my arm instead of my knee, and it doesn’t get better when I stay still.”

From there, we moved towards effective pain treatment. Sometimes words work better than numbers.

Joshua Pate, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of Technology Sydney; Dale J. Langford, Associate Professor of Pain Management Research in Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University, and Tory Madden, Associate Professor and Pain Researcher, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Genius Foods – by Max Lugavere

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There is a lot of seemingly conflicting (or sometimes: actually conflicting!) information out there with regard to nutrition and various aspects of health. Why, for example, are we told:

- Be sure to get plenty of good healthy fats from nuts and seeds, for metabolic health and brain health too!

- But these terrible nut and seed oils lead to heart disease and dementia! Avoid them at all costs!

Max Lugavere demystifies this and more.

His science-led approach is primarily focused on avoiding dementia, and/but is at least not bad when it comes to other areas of health too.

He takes us on a tour of different parts of our nutrition, including:

- Perhaps the clearest explanation of “healthy” vs “unhealthy” fats this reviewer has read

- Managing carbs (simple and complex) for healthy glucose management—essential for good brain health

- What foods to improve or reduce—a lot you might guess, but this is a comprehensive guide to brain health so it’d be remiss to skip it

- The role that intermittent fasting can play as a bonus extra

While the main thrust of the book is about avoiding cognitive impairment in the long-term (including later-life dementia), he makes good, evidence-based arguments for how this same dietary plan improves cognitive function in the short-term, too.

Speaking of that dietary plan: he does give a step-by-step guide in a “make this change first, then this, then this” fashion, and offers some sample recipes too. This is by no means a recipe book though—most of the book is taking us through the science, not the kitchen.

Bottom line: this is the book for getting unconfused with regard to diet and brain health, making a lot of good science easy to understand. Which we love!

Click here to check out “Genius Foods” on Amazon today, give your brain a boost!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: