Revealed: The Soviet Secret Recipe For Success That The CIA Admits Put The US To Shame

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Today’s edition of 10almonds brings you a blast from the past with a modern twist: an ancient Russian peasant food that became a Soviet staple, and today, is almost unknown in the West.

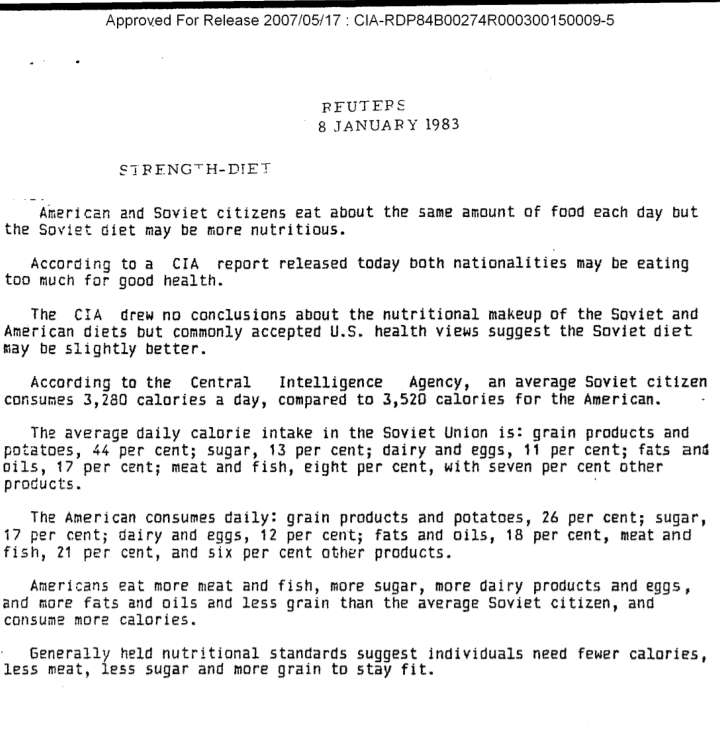

Before we get to that, let’s take a sneaky look at this declassified CIA memorandum from near the end of the Cold War:

(Click here to see a bigger version)

The take-away here is:

- Americans were eating 2–3 times more meat than Soviets

- Soviets were eating nearly double the amount of grain products and potatoes

…and both of these statistics meant that nutritionally speaking, the Soviets were doing better.

Americans also consumed more sugar and fats, which again, wasn’t the best dietary option.

But was the American diet tastier? Depends on whom you ask.

Which brings us to a literal recipe we’re going to be sharing with you today:

It’s not well-known in the West, but in Russia, it’s a famous national comfort food, a bastion of health and nutrition, and it rose to popularity because it was not only cheap and nutritious, but also, you could eat it for days without getting sick of it. And it could be easily frozen for reheating later without losing any of its appeal—it’d still be just as good.

In Russia there are sayings about it:

Щи да каша — пища наша (Shchi da kasha — pishcha nasha)

“Shchi and buckwheat are what we eat”

Top tip: buckwheat makes an excellent (and naturally sweet) alternative to porridge oats if prepared the same way!

Где щи, там и нас ищи (Gdye shchi, tam i nas ishchi)

“Where there’s shchi, us you’ll see”

Голь голью, а луковка во щах есть (Gol’ gol’yu, a lukovka vo shchakh yest’)

“I’m stark naked, but there’s shchi with onions”

There’s a very strong sentiment in Russia that really, all you need is shchi (shchi, shchi… shchi is all you need )

But what, you may ask, is shchi?

Our culinary cultural ambassador Nastja is here to offer her tried-and-tested recipe for…

…Russian cabbage soup (yes, really—bear with us now, and you can thank us later)

There are a lot of recipes for shchi (see for yourself what the Russian version of Lifehacker recommends), and we’ll be offering our favorite…

Nastja’s Nutritious and Delicious Homemade Shchi

Hi, Nastja here! I’m going to share with you my shchi recipe that is:

- Cheap

- So tasty

- Super nutritious*

- Vegan

- Gluten Free

You will also need:

- A cabbage (I use sweetheart, but any white cabbage will do)

- 1 cup (250g) red lentils (other kinds of lentils will work too)

- ½ lb or so (250–300g) tomatoes (I use baby plum tomatoes, but any kind will do)

- ½ lb or so (250–300g) mushrooms (the edible kind)

- An onion (I use a brown onion; any kind will do)

- Salt, pepper, rosemary, thyme, parsley, cumin

- Marmite or similar yeast extract (do you hate it? Me too. Trust me, it’ll be fine, you’ll love it. Omit if you’re a coward.)

- A little oil for sautéing (I use sunflower, but canola is fine, as is soy oil. Do not use olive oil or coconut oil, because the taste is too strong and the flashpoint too low)

First, what the French call mise-en-place, the prep work:

- Chop the cabbage into small strips, ⅛–¼ inch x 1 inch is a good guideline, but you can’t really go wrong unless you go to extremes

- Chop the tomatoes. If you’re using baby plum tomatoes (or cherry tomatoes), cut them in half. If using larger tomatoes, cut them into eighths (halve them, halve the halves, then halve the quarters)

- Chop the mushrooms. If using button mushrooms, half them. If using larger mushrooms, quarter them.

- Chop the onion finely.

- Gather the following kitchenware: A big pan (stock pot or similar), a sauté pan (a big wok or frying pan will do), a small frying pan (here a wok will not do), and a saucepan (a rice cook will also do)

Now, for actual cooking:

- Cook the red lentils until soft (I use a rice cooker, but a saucepan is fine) and set aside

- Sauté the cabbage, put it in the big pot (not yet on the heat!)

- Fry the mushrooms, put them in the big pot (still not yet on the heat!)

When you’ve done this a few times and/or if you’re feeling confident, you can do the above simultaneously to save time

- Blend the lentils into the water you cooked them in, and then add to the big pot.

- Turn the heat on low, and if necessary, add more water to make it into a rich soup

- Add the seasonings to taste, except the parsley. Go easy on the cumin, be generous with the rosemary and thyme, let your heart guide you with the salt and pepper.

- When it comes to the yeast extract: add about one teaspoon and stir it into the pot. Even if you don’t like Marmite, it barely changes the flavour (makes it slightly richer) and adds a healthy dose of vitamin B12.

We did not forget the tomatoes and the onion:

- Caramelize the onion (keep an eye on the big pot) and set it aside

- Fry the tomatoes and add them to the big pot

Last but definitely not least:

- Serve!

- The caramelized onion is a garnish, so put a little on top of each bowl of shchi

- The parsley is also a garnish, just add a little

Any shchi you don’t eat today will keep in the fridge for several days, or in the freezer for much longer.

*That nutritious goodness I talked about? Check it out:

- Lentils are high in protein and iron

- Cabbage is high in vitamin C and calcium

- Mushrooms are high in magnesium

- Tomatoes are good against inflammation

- Black pepper has a host of health benefits

- Yeast extract contains vitamin B12

Let us know how it went! We love to receive emails from our subscribers!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What are the most common symptoms of menopause? And which can hormone therapy treat?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Despite decades of research, navigating menopause seems to have become harder – with conflicting information on the internet, in the media, and from health care providers and researchers.

Adding to the uncertainty, a recent series in the Lancet medical journal challenged some beliefs about the symptoms of menopause and which ones menopausal hormone therapy (also known as hormone replacement therapy) can realistically alleviate.

So what symptoms reliably indicate the start of perimenopause or menopause? And which symptoms can menopause hormone therapy help with? Here’s what the evidence says.

Remind me, what exactly is menopause?

Menopause, simply put, is complete loss of female fertility.

Menopause is traditionally defined as the final menstrual period of a woman (or person female at birth) who previously menstruated. Menopause is diagnosed after 12 months of no further bleeding (unless you’ve had your ovaries removed, which is surgically induced menopause).

Perimenopause starts when menstrual cycles first vary in length by seven or more days, and ends when there has been no bleeding for 12 months.

Both perimenopause and menopause are hard to identify if a person has had a hysterectomy but their ovaries remain, or if natural menstruation is suppressed by a treatment (such as hormonal contraception) or a health condition (such as an eating disorder).

What are the most common symptoms of menopause?

Our study of the highest quality menopause-care guidelines found the internationally recognised symptoms of the perimenopause and menopause are:

- hot flushes and night sweats (known as vasomotor symptoms)

- disturbed sleep

- musculoskeletal pain

- decreased sexual function or desire

- vaginal dryness and irritation

- mood disturbance (low mood, mood changes or depressive symptoms) but not clinical depression.

However, none of these symptoms are menopause-specific, meaning they could have other causes.

In our study of Australian women, 38% of pre-menopausal women, 67% of perimenopausal women and 74% of post-menopausal women aged under 55 experienced hot flushes and/or night sweats.

But the severity of these symptoms varies greatly. Only 2.8% of pre-menopausal women reported moderate to severely bothersome hot flushes and night sweats symptoms, compared with 17.1% of perimenopausal women and 28.5% of post-menopausal women aged under 55.

So bothersome hot flushes and night sweats appear a reliable indicator of perimenopause and menopause – but they’re not the only symptoms. Nor are hot flushes and night sweats a western society phenomenon, as has been suggested. Women in Asian countries are similarly affected.

You don’t need to have night sweats or hot flushes to be menopausal.

Maridav/ShutterstockDepressive symptoms and anxiety are also often linked to menopause but they’re less menopause-specific than hot flushes and night sweats, as they’re common across the entire adult life span.

The most robust guidelines do not stipulate women must have hot flushes or night sweats to be considered as having perimenopausal or post-menopausal symptoms. They acknowledge that new mood disturbances may be a primary manifestation of menopausal hormonal changes.

The extent to which menopausal hormone changes impact memory, concentration and problem solving (frequently talked about as “brain fog”) is uncertain. Some studies suggest perimenopause may impair verbal memory and resolve as women transition through menopause. But strategic thinking and planning (executive brain function) have not been shown to change.

Who might benefit from hormone therapy?

The Lancet papers suggest menopause hormone therapy alleviates hot flushes and night sweats, but the likelihood of it improving sleep, mood or “brain fog” is limited to those bothered by vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats).

In contrast, the highest quality clinical guidelines consistently identify both vasomotor symptoms and mood disturbances associated with menopause as reasons for menopause hormone therapy. In other words, you don’t need to have hot flushes or night sweats to be prescribed menopause hormone therapy.

Often, menopause hormone therapy is prescribed alongside a topical vaginal oestrogen to treat vaginal symptoms (dryness, irritation or urinary frequency).

You don’t need to experience hot flushes and night sweats to take hormone therapy.

Monkey Business Images/ShutterstockHowever, none of these guidelines recommend menopause hormone therapy for cognitive symptoms often talked about as “brain fog”.

Despite musculoskeletal pain being the most common menopausal symptom in some populations, the effectiveness of menopause hormone therapy for this specific symptoms still needs to be studied.

Some guidelines, such as an Australian endorsed guideline, support menopause hormone therapy for the prevention of osteoporosis and fracture, but not for the prevention of any other disease.

What are the risks?

The greatest concerns about menopause hormone therapy have been about breast cancer and an increased risk of a deep vein clot which might cause a lung clot.

Oestrogen-only menopause hormone therapy is consistently considered to cause little or no change in breast cancer risk.

Oestrogen taken with a progestogen, which is required for women who have not had a hysterectomy, has been associated with a small increase in the risk of breast cancer, although any risk appears to vary according to the type of therapy used, the dose and duration of use.

Oestrogen taken orally has also been associated with an increased risk of a deep vein clot, although the risk varies according to the formulation used. This risk is avoided by using estrogen patches or gels prescribed at standard doses

What if I don’t want hormone therapy?

If you can’t or don’t want to take menopause hormone therapy, there are also effective non-hormonal prescription therapies available for troublesome hot flushes and night sweats.

In Australia, most of these options are “off-label”, although the new medication fezolinetant has just been approved in Australia for postmenopausal hot flushes and night sweats, and is expected to be available by mid-year. Fezolinetant, taken as a tablet, acts in the brain to stop the chemical neurokinin 3 triggering an inappropriate body heat response (flush and/or sweat).

Unfortunately, most over-the-counter treatments promoted for menopause are either ineffective or unproven. However, cognitive behaviour therapy and hypnosis may provide symptom relief.

The Australasian Menopause Society has useful menopause fact sheets and a find-a-doctor page. The Practitioner Toolkit for Managing Menopause is also freely available.

Susan Davis, Chair of Women’s Health, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Focusing On Health In Our Sixties

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝What happens when you age in your sixties?❞

The good news is, a lot of that depends on you!

But, speaking on averages:

While it’s common for people to describe being over 50 as being “over the hill”, halfway to a hundred, and many greetings cards and such reflect this… Biologically speaking, our 60s are more relevant as being halfway to our likely optimal lifespan of 120. Humans love round numbers, but nature doesn’t care for such.

- In our 60s, we’re now usually the “wrong” side of the menopausal metabolic slump (usually starting at 45–55 and taking 5–10 years), or the corresponding “andropause” where testosterone levels drop (usually starting at 45 and a slow decline for 10–15 years).

- In our 60s, women will now be at a higher risk of osteoporosis, due to the above. The risk is not nearly so severe for men.

- In our 60s, if we’re ever going to get cancer, this is the most likely decade for us to find out.

- In our 60s, approximately half of us will suffer some form of hearing loss

- In our 60s, our body has all but stopped making new T-cells, which means our immune defenses drop (this is why many vaccines/boosters are offered to over-60s, but not to younger people)

While at first glance this does not seem a cheery outlook, knowledge is power.

- We can take HRT to avoid the health impact of the menopause/andropause

- We can take extra care to look after our bone health and avoid osteoporosis

- We can make sure we get the appropriate cancer screenings when we should

- We can take hearing tests, and if appropriate find the right hearing aids for us

- We can also learn to lip-read (this writer relies heavily on lip-reading!)

- We can take advantage of those extra vaccinations/boosters

- We can take extra care to boost immune health, too

Your body has no idea how many times you’ve flown around the sun and nor does it care. What actually makes a difference to it, is how it has been treated.

See also: Milestone Medical Tests You Should Take in Your 60s, 70s, and Beyond

Share This Post

-

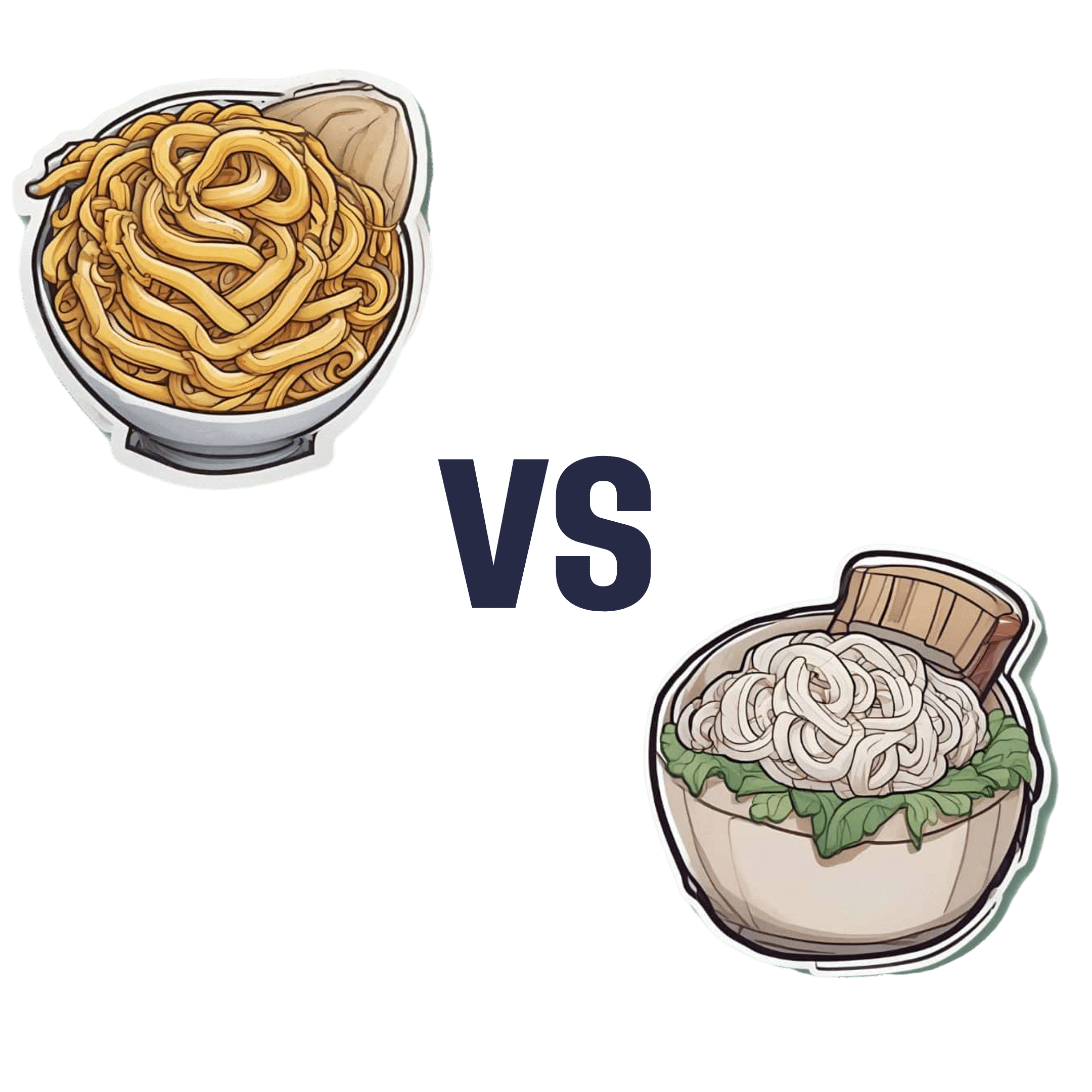

Egg Noodles vs Rice Noodles – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing egg noodles to rice noodles, we picked the egg noodles.

Why?

It was close—these are both quite mediocre foods. They’re neither amazing for the health nor appalling for the health (in moderation). They are both relatively low in nutrients, but they are also low in anti-nutrients, i.e. things that have a negative effect on the health.

Their mineral profiles are similar; both are a source of selenium, manganese, phosphorus, copper, and iron. Not as good as many sources, but not devoid of nutrients either.

Their vitamin profiles are both pitiful; rice noodles have trace amounts of various vitamins, and egg noodles have only slightly more. While eggs themselves are nutritious, the processing has robbed them of much of their value.

In terms of macros, egg noodles have a little more fat (but the fats are healthier) and rice noodles have a lot more carbs, so this is the main differentiator, and is the main reason we chose the egg noodles over the rice noodles. Both have a comparable (small) amount of protein.

In short:

- They’re comparable on minerals, and vitamins here are barely worth speaking about (though egg noodles do have marginally more)

- Egg noodles have a little more fat (but the fats are healthier)

- Rice noodles have a lot more carbs (with a moderately high glycemic index, which is relatively worse—if you eat them with vegetables and fats, then that’ll offset this, but we’re judging the two items on merit, not your meal)

Learn more

You might like this previous main feature of ours:

Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Hydroxyapatite Toothpaste – 6 Month Update

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A dental hygienist tried hydroxyapatite toothpaste for 6 months, and this is what she found:

The results are in

In few words: she took before-and-after photos, or rather, regular photos through the 6-month process.

What she was mostly looking for: tooth translucency, enamel imperfections, and stains.

What she found: a slight improvement within two months, though over the course of the six months, the photos were somewhat inconsistent—however, this may have more to do with the machinations of her camera, the ambient lighting, etc, than it has to do with the toothpaste. In an ideal world, she’d be able to do a density test with a laser on one side and a sensor on the other, but it seems her budget didn’t stretch to that. In terms of subjective improvement, she found that her teeth felt better, even if the visual change was not consistently apparent.

This is consistent with the idea that hydroxyapatite toothpaste can mineralize teeth throughout the tooth, not just from the outside in, due to the porous nature of the enamel. So, a lot of the change may have been on the inside.

Ultimately, she neither recommends nor discommends the toothpaste, and acknowledges that more time, up to a year, may be needed for more noticeable results.

For more on all of this plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Tooth Remineralization: How To Heal Your Teeth Naturally

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gut Health and Anxiety

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I’d like to read articles on gut health and anxiety❞

We hope you caught yesterday’s edition of 10almonds, which touched on both of those! Other past editions you might like include:

We’ll be sure to include more going forward, too!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem. What should we call mental distress?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We talk about mental health more than ever, but the language we should use remains a vexed issue.

Should we call people who seek help patients, clients or consumers? Should we use “person-first” expressions such as person with autism or “identity-first” expressions like autistic person? Should we apply or avoid diagnostic labels?

These questions often stir up strong feelings. Some people feel that patient implies being passive and subordinate. Others think consumer is too transactional, as if seeking help is like buying a new refrigerator.

Advocates of person-first language argue people shouldn’t be defined by their conditions. Proponents of identity-first language counter that these conditions can be sources of meaning and belonging.

Avid users of diagnostic terms see them as useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can box people in and misrepresent their problems as pathologies.

Underlying many of these disagreements are concerns about stigma and the medicalisation of suffering. Ideally the language we use should not cast people who experience distress as defective or shameful, or frame everyday problems of living in psychiatric terms.

Our new research, published in the journal PLOS Mental Health, examines how the language of distress has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here’s what we found.

Engin Akyurt/Pexels Generic terms for the class of conditions

Generic terms – such as mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem – have largely escaped attention in debates about the language of mental ill health. These terms refer to mental health conditions as a class.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include mental, mental health, psychiatric and psychological, and common nouns include condition, disease, disorder, disturbance, illness, and problem. Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ in their connotations. Disease and illness sound the most medical, whereas condition, disturbance and problem need not relate to health. Mental implies a direct contrast with physical, whereas psychiatric implicates a medical specialty.

Mental health problem, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathologising. It implies that something is to be solved rather than treated, makes no direct reference to medicine, and carries the positive connotations of health rather than the negative connotation of illness or disease.

Is ‘mental health problem’ actually less pathologising? Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock Arguably, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls the “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency for language to evolve new terms to escape (at least temporarily) the offensive connotations of those they replace.

English linguist Hazel Price argues that mental health has increasingly come to replace mental illness to avoid the stigma associated with that term.

How has usage changed over time?

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the popularity of 24 generic terms: every combination of the nouns and adjectives listed above.

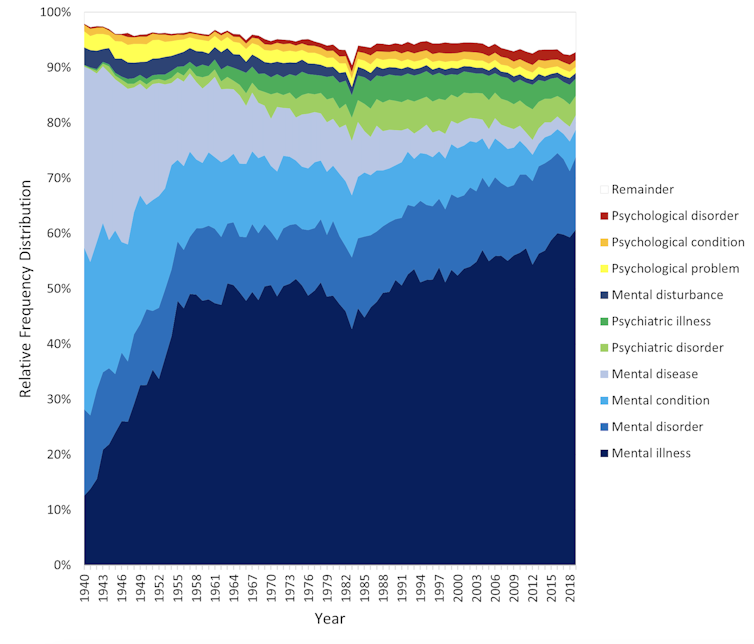

We explore the frequency with which each term appears from 1940 to 2019 in two massive text data sets representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The findings are very similar in both data sets.

The figure presents the relative popularity of the top ten terms in the larger data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined into the remainder.

Relative popularity of alternative generic terms in the Google Books corpus. Haslam et al., 2024, PLOS Mental Health. Several trends appear. Mental has consistently been the most popular adjective component of the generic terms. Mental health has become more popular in recent years but is still rarely used.

Among nouns, disease has become less widely used while illness has become dominant. Although disorder is the official term in psychiatric classifications, it has not been broadly adopted in public discourse.

Since 1940, mental illness has clearly become the preferred generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, it has steadily risen in popularity.

Does it matter?

Our study documents striking shifts in the popularity of generic terms, but do these changes matter? The answer may be: not much.

One study found people think mental disorder, mental illness and mental health problem refer to essentially identical phenomena.

Other studies indicate that labelling a person as having a mental disease, mental disorder, mental health problem, mental illness or psychological disorder makes no difference to people’s attitudes toward them.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, but the evidence to date suggests they are minimal.

The labels we use may not have a big impact on levels of stigma. Pixabay/Pexels Is ‘distress’ any better?

Recently, some writers have promoted distress as an alternative to traditional generic terms. It lacks medical connotations and emphasises the person’s subjective experience rather than whether they fit an official diagnosis.

Distress appears 65 times in the 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing Act, usually in the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By implication, distress is a broad concept akin to but not synonymous with mental ill health.

But is distress destigmatising, as it was intended to be? Apparently not. According to one study, it was more stigmatising than its alternatives. The term may turn us away from other people’s suffering by amplifying it.

So what should we call it?

Mental illness is easily the most popular generic term and its popularity has been rising. Research indicates different terms have little or no effect on stigma and some terms intended to destigmatise may backfire.

We suggest that mental illness should be embraced and the proliferation of alternative terms such as mental health problem, which breed confusion, should end.

Critics might argue mental illness imposes a medical frame. Philosopher Zsuzsanna Chappell disagrees. Illness, she argues, refers to subjective first-person experience, not to an objective, third-person pathology, like disease.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centres the individual and their connections. “When I identify my suffering as illness-like,” Chappell writes, “I wish to lay claim to a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As generic terms go, mental illness is a healthy option.

Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne and Naomi Baes, Researcher – Social Psychology/ Natural Language Processing, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: