Kava vs Anxiety

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

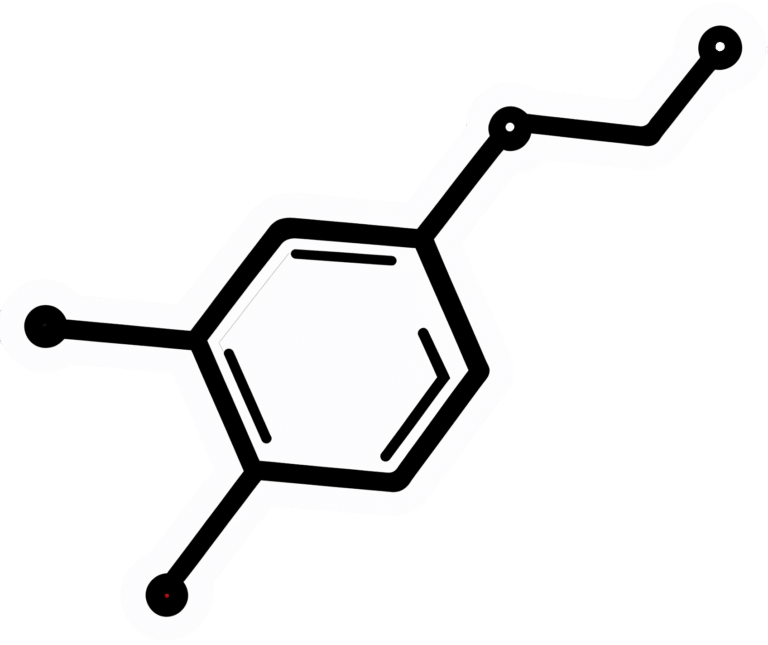

Kava, sometimes also called “kava kava” but we’re just going to call it kava once for the sake of brevity, is a heart-shaped herb that bestows the powers of the Black Panther is popularly enjoyed for its anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effects. Despite the similarity of the name in many languages, it is unrelated to coffee (except insofar as they are both plants), and its botanical name is Piper methysticum.

Does it work?

Yes! At least in the short-term; more on that later.

Firstly, you may be wondering how it works; it works by its potentiation of GABA receptors in the brain. GABA (or gamma-aminobutyric acid, to give it its full name), as you may recall, is a neurotransmitter that is associated with feelings of calm; we wrote about it here:

So, what does “potentiation of GABA receptors” mean? It means… Scientists don’t for 100% sure know how it works yet, but it does make GABA receptors fire more. It’s possible that to some degree GABA fits the “molecular lock” of the receptors and causes them to say “GABA is here”; it’s also possible that they just make them more sensitive to the real GABA that is there, or there could be another explanation as yet undiscovered. Either way, it means that taking kava has a similar effect to having increased GABA levels in the brain:

As for how much to use, 20–300mg appears to be an effective dose, and most sources recommend 80–250mg:

Kava as a Clinical Nutrient: Promises and Challenges

This review of clinical trials found that it was more effective than placebo in only 3 of 7 trials; specifically, it was beneficial in the short-term and not in the long-term. For these reasons, the researchers concluded:

❝Kava Kava appears to be a short-term treatment for anxiety, but not a replacement for prolonged anti-anxiety use. Although not witnessed in this review, liver toxicity is especially possible if taken longer than 8 weeks.❞

Another review of clinical trials found better results over the course of 11 clinical trials, though again, short-term treatment only was considered to be where the “safe and effective” claim can be placed:

❝Compared with placebo, kava extract appears to be an effective symptomatic treatment option for anxiety. The data available from the reviewed studies suggest that kava is relatively safe for short-term treatment (1 to 24 weeks), although more information is required. Further rigorous investigations, particularly into the long-term safety profile of kava are warrant❞

Source: Kava extract for treating anxiety

Is it safe?

Nope! It has been associated with liver damage:

The likely main mechanism of toxicity is that it simply monopolizes the liver’s metabolic abilities, meaning that while it’s metabolizing the kava, it’s not metabolizing other things (such as alcohol or other medications), which will then build up, and potentially overwhelm the liver:

Constituents in kava extracts potentially involved in hepatotoxicity: a review

However, traditionally-prepared kava has not had the same effect as modern extracts; at first it seemed the difference was the traditional aqueous extracts vs modern acetonic/ethanolic extracts, but eventually that was found not to be the case, as toxicity occurred with industrial aqueous extracts too. The conclusion so far is that it is about the quality of the source ingredients, and the problems inherent to mass-production:

Meanwhile, short-term use doesn’t seem to have this problem, if you’re not drinking alcohol or taking medications that affect the liver:

Mechanisms/risk factors – kava-associated hepatotoxicity ← you’ll need to scroll down to 4.2.4 to read about this

Want to try it?

If the potential for hepatotoxicity doesn’t put you off, here’s an example product on Amazon ← we do not recommend it, but we are not the boss of you, and maybe you’re confident about your liver and want to use it only very short-term?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Best Kind Of Fiber For Overall Health?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Fiber Of Good Health

We’ve written before about how most people in industrialized nations in general, and N. America in particular, do not get nearly enough fiber:

Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

Fiber’s important for many aspects of health, not least of all the heart:

What Matters Most For Your Heart? Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

As well, of course, as being critical for gut health:

Gut Health 101: Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

But is all fiber “prebiotic fiber”, and/or are some better than others?

Beta-glucan

A recent study (it’s a mouse study, but promising in its applicability for humans) examined the health impacts of 5 different fiber types:

- pectin

- β-glucan

- wheat dextrin

- resistant starch

- cellulose (control)

As for health metrics, they measured:

- body weight

- adiposity

- indirect calorimetry

- glucose tolerance

- gut microbiota

- metabolites thereof

What they found was…

❝Only β-glucan supplementation during HFD-feeding decreased adiposity and body weight gain and improved glucose tolerance compared with HFD-cellulose, whereas all other fibers had no effect. This was associated with increased energy expenditure and locomotor activity in mice compared with HFD-cellulose.

All fibers supplemented into an HFD uniquely shifted the intestinal microbiota and cecal short-chain fatty acids; however, only β-glucan supplementation increased cecal butyrate concentrations. Lastly, all fibers altered the small-intestinal microbiota and portal bile acid composition. ❞

If you’d like to read more, the study itself is here:

If you’d like to read less, the short version is that they are all good but β-glucan scored best in several metrics.

It also acts indirectly as a GLP-1 agonist, by the way:

The right fiber may help you lose weight

You may be wondering: what is β-glucan found in?

It’s found in many (non-animal product) foods, but oats, barley, mushrooms, and yeasts are all good sources.

Is it available as a supplement?

More or less; there are supplements that contain it generously, here’s an example product on Amazon, a cordyceps extract, of which >30% is β-glucan.

As an aside, cordyceps itself has many other healthful properties too:

Cordyceps: Friend Or Foe? ← the answer is, it depends! If you’re human, it’s a friend.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

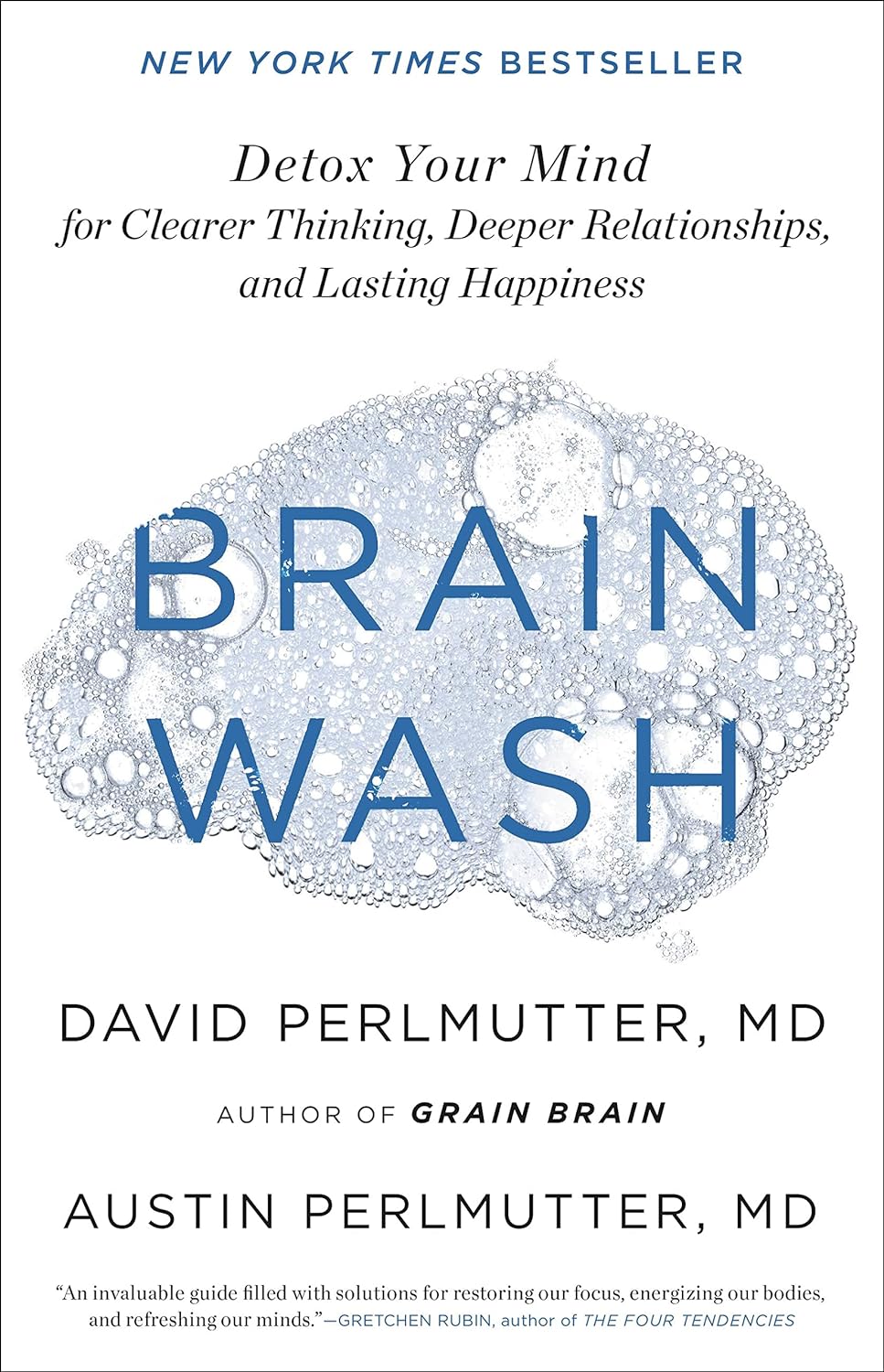

Brain Wash – by Dr. David Perlmutter, Dr. Austin Perlmutter, and Kristen Loberg

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may be familiar with the lead author of this book, Dr. David Perlmutter, as a big name in the world of preventative healthcare. A lot of his work has focused specifically on carbohydrate metabolism, and he is as associated with grains and he is with brains. This book focuses on the latter.

Dr. Perlmutter et al. take a methodical look at all that is ailing our brains in this modern world, and systematically lay out a plan for improving each aspect.

The advice is far from just dietary, though the chapter on diet takes a clear stance:

❝The food you eat and the beverages you drink change your emotions, your thoughts, and the way you perceive the world❞

The style is explanatory, and the book can be read comfortably as a “sit down and read it cover to cover” book; it’s an enjoyable, informative, and useful read.

Bottom line: if you’d like to give your brain a gentle overhaul, this is the one-stop-shop book to give you the tools to do just that.

Share This Post

-

The Paleo Diet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s The Real Deal With The Paleo Diet?

The Paleo diet is popular, and has some compelling arguments for it.

Detractors, meanwhile, have derided Paleo’s inclusion of modern innovations, and have also claimed it’s bad for the heart.

But where does the science stand?

First: what is it?

The Paleo diet looks to recreate the diet of the Paleolithic era—in terms of nutrients, anyway. So for example, you’re perfectly welcome to use modern cooking techniques and enjoy foods that aren’t from your immediate locale. Just, not foods that weren’t a thing yet. To give a general idea:

Paleo includes:

- Meat and animal fats

- Eggs

- Fruits and vegetables

- Nuts and seeds

- Herbs and spices

Paleo excludes:

- Processed foods

- Dairy products

- Refined sugar

- Grains of any kind

- Legumes, including any beans or peas

Enjoyers of the Mediterranean Diet or the DASH heart-healthy diet, or those with a keen interest in nutritional science in general, may notice they went off a bit with those last couple of items at the end there, by excluding things that scientific consensus holds should be making up a substantial portion of our daily diet.

But let’s break it down…

First thing: is it accurate?

Well, aside from the modern cooking techniques, the global market of goods, and the fact it does include food that didn’t exist yet (most fruits and vegetables in their modern form are the result of agricultural engineering a mere few thousand years ago, especially in the Americas)…

…no, no it isn’t. Best current scientific consensus is that in the Paleolithic we ate mostly plants, with about 3% of our diet coming from animal-based foods. Much like most modern apes.

Ok, so it’s not historically accurate. No biggie, we’re pragmatists. Is it healthy, though?

Well, health involves a lot of factors, so that depends on what you have in mind. But for example, it can be good for weight loss, almost certainly because of cutting out refined sugar and, by virtue of cutting out all grains, that means having cut out refined flour products, too:

Diet Review: Paleo Diet for Weight Loss

Measured head-to-head with the Mediterranean diet for all-cause mortality and specific mortality, it performed better than the control (Standard American Diet, or “SAD”), probably for the same reasons we just mentioned. However, it was outperformed by the Mediterranean Diet:

So in lay terms: the Paleo is definitely better than just eating lots of refined foods and sugar and stuff, but it’s still not as good as the Mediterranean Diet.

What about some of the health risk claims? Are they true or false?

A common knee-jerk criticism of the paleo-diet is that it’s heart-unhealthy. So much red meat, saturated fat, and no grains and legumes.

The science agrees.

For example, a recent study on long-term adherence to the Paleo diet concluded:

❝Results indicate long-term adherence is associated with different gut microbiota and increased serum trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a gut-derived metabolite associated with cardiovascular disease. A variety of fiber components, including whole grain sources may be required to maintain gut and cardiovascular health.❞

Bottom line:

The Paleo Diet is an interesting concept, and certainly can be good for short-term weight loss. In the long-term, however (and: especially for our heart health) we need less meat and more grains and legumes.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Healing Arthritis – by Dr. Susan Blum

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We previously reviewed another book by this author, her Immune System Recovery Plan, and today it’s more specific: healing arthritis

Of course, not all arthritis is rooted in immune dysfunction, but a) all of it is made worse by immune dysfunction and b) rheumatoid arthritis, which is an autoimmune disease, affects 1% of the population.

This book tackles all kinds of arthritis, by focusing on addressing the underlying causes and treating those, and (whether it was the cause or not) reducing inflammation without medication, because that will always help.

The “3 steps” mentioned in the subtitle are three stages of a plan to improve the gut microbiome in such a way that it not only stops worsening your arthritis, but starts making it better.

The style here is on the hard end of pop-science, so if you want something more conversational/personable, then this won’t be so much for you, but if you just want the information and explanation, then this does it just fine, and it has frequent references to the science to back it up, with a reassuringly extensive bibliography.

Bottom line: if you have arthritis and want a book that will help you to get either symptom-free or as close to that as is possible from your current condition (bearing in mind that arthritis is generally degenerative), then this is a great book for that.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Hero Homemade Hummus

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you only have store-bought hummus at home, you’re missing out. The good news is that hummus is very easy to make, and highly customizable—so once you know how to make one, you can make them all, pretty much. And of course, it’s one of the healthiest dips out there!

You will need

- 2 x 140z/400g tins chickpeas

- 4 heaped tbsp tahini

- 3 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- Juice of 1 lemon

- 1 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- Optional, but recommended: your preferred toppings/flavorings. Examples to get you started include olives, tomatoes, garlic, red peppers, red onion, chili, cumin, paprika (please do not put everything in one hummus; if unsure about pairings, select just one optional ingredient per hummus for now)

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Drain the chickpeas, but keep the chickpea water from them (also called aquafaba; it has many culinary uses beyond the scope of today’s recipe, but for now, just keep it to one side).

2) Add the chickpeas, ⅔ of the aquafaba, the tahini, the olive oil, the lemon juice, the black pepper, and any optional extra flavoring(s) that you don’t want to remain chunky. Blend until smooth; if it becomes to thick, add a little more aquafaba and blend again until it’s how you want it.

3) Transfer the hummus to a bowl, and add any extra toppings.

4) Repeat the above steps for each different kind of hummus you want to make.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

- All About Olive Oils

- Tasty Polyphenols

- Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

When Doctors Make House Calls, Modern-Style!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

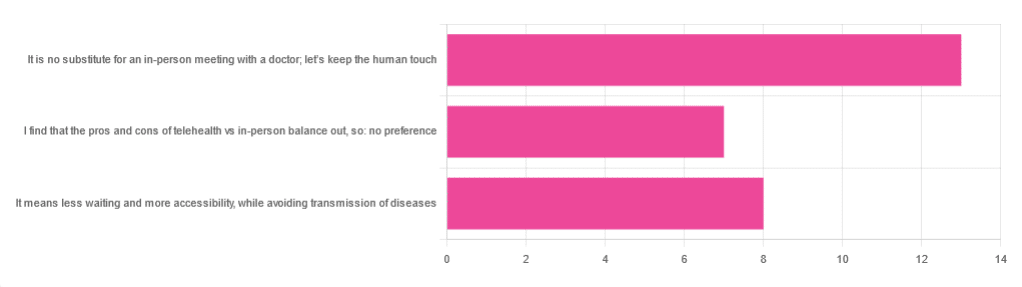

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you foryour opinion of telehealth for primary care consultations*, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 46% said “It is no substitute for an in-person meeting with a doctor; let’s keep the human touch”

- About 29% said “It means less waiting and more accessibility, while avoiding transmission of diseases”

- And 25 % said “I find that the pros and cons of telehealth vs in-person balance out, so: no preference”

*We specified that by “primary care” we mean the initial consultation with a non-specialist doctor, before receiving treatment or being referred to a specialist. By “telehealth” we mean by videocall or phonecall.

So, what does the science say?

A quick note first

Because telehealth was barely a thing (statistically speaking) before the first stages of the COVID pandemic, compared to how it is now, most of the science for this is young, and a lot of the science simply hasn’t been done yet, and/or has not been published yet, because the process can take years.

Because of this, some studies we do have aren’t specifically about primary care, and are sometimes about specialists. We think this should not affect the results much, but it bears highlighting.

Nevertheless, we’ll do what we can with the science we have!

Telehealth is more accessible than in-person consultations: True or False?

True, for most people. For example…

❝Data was found from a variety of emergency and non-emergency departments of primary, secondary, and specialised healthcare.

Satisfaction was high among recipients of healthcare, scoring 9-10 on a scale of 0-10 or ranging from 73.3% to 100%.

Convenience was rated high in every specialty examined. Satisfaction of clinicians was high throughout the specialities despite connection failure and concerns about confidentiality of information.❞

whereas…

❝Nonetheless, studies reported perception of increased barriers to accessing care and inequalities for vulnerable patients especially in older people❞

~ Ibid.

Source: Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review

Now, perception of those things does necessarily equate to an actual increased barrier, but it is reasonable that someone who thinks something is inaccessible will be less inclined to try to access it.

The quality of care provided via telehealth is as good as in-person: True or False?

True, ostensibly, with caveats. The caveats are:

- We’re going offreported patient satisfaction, not objective patient health outcomes (we found little* science as yet for the relative incidence of misdiagnosis, for example—which kind of thing will take time to be revealed).

- We’re also therefore speaking (as statistics do) for the significant majority of people. However, if we happen to be (statistically speaking) an insignificant minority, well, that just sucks for us personally.

*we did find some, but it wasn’t very helpful yet. For example:

An electronic trigger to detect telemedicine-related diagnostic errors

this one does look at the incidence of diagnostic errors, but provides no control group (i.e. otherwise-comparable in-person consultations) for comparison.

While most oft-considered demographic groups reported comparable patient satisfaction (per race, gender, and socioeconomic status, for example), there was one outlier variable, which was age (as we quoted from that first study above).

However!

Looking under the hood of these stats, it seems that age is not the real culprit, so much as technological illiteracy, which is heavily correlated with age:

❝Lower eHealth literacy is associated with more negative attitudes towards I/C technology in healthcare. This trend is consistent across diverse demographics and regions. ❞

Source: Meta-analysis: eHealth literacy and attitudes towards internet/computer technology

There are things that can be done at an in-person consultation that can’t be done by telehealth: True or False?

True, of course. It is incredibly rare that we will cite “common sense”, (as sometimes “common sense” is actually “common mistakes” and is simply and verifiably wrong), but in this case, as one 10almonds subscriber put it:

❝The doctor uses his five senses to assess. This cannot be attained over the phone❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

A quick note first: if your doctor is using their sense of taste to diagnose you, please get a different doctor, because they should definitely not be doing that!

Not in this century, anyway… Once upon a time, diabetes was diagnosed by urine-tasting (and yes, that was a fairly reliable method).

However, nowadays indeed a doctor will use sight, sound, touch, and sometimes even smell.

In a videocall we’re down to two of those senses (sight and sound), and in a phonecall, down to one (sound) and even that is hampered. Your doctor cannot, for example, use a stethoscope over the phone.

With this in mind, it really comes down to what you need from your doctor in that consultation.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is to be prescribed an antidepressant, that probably doesn’t need a full physical.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is a referral, chances are that’ll be fine by telehealth too.

- If your doctor is 99% sure that what you need is a verbal check-up (e.g. “How’s it been going for you, with the medication that I prescribed for you a month ago?”, then again, a call is probably fine.

If you have a worrying lump, or an unhappy bodily discharge, or an unexplained mysterious pain? These things, more likely an in-person check-up is in order.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: