6 Signs Of Stroke (One Month In Advance)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most people can recognise the signs of a stroke when it’s just happened, but knowing the signs that appear a month beforehand would be very useful. That’s what this video’s about!

The Warning Signs

- Persistently elevated blood pressure: one more reason to have an at-home testing kit and use it regularly! Or a smartwatch or similar that’ll do it for you. The reason this is relevant is because high blood pressure can lead to damaging blood vessels, causing a stroke.

- Excessive fatigue: of course, this one can have many possible causes, but one of them is a “transient ischemic attack” (TIA), which is essentially a micro-stroke, and can be a precursor to a more severe stroke. So, we’re not doing the Google MD thing here of saying “if this, then that”, but we are saying: paying attention to the overall patterns can be very useful. Rather than fretting unduly about a symptom in isolation, see how it fits into the big picture.

- Vision problems: especially if sudden-onset with no obvious alternative cause can be a sign of neural damage, and may indicate a stroke on the way.

- Speech problems: if there’s not an obvious alternative explanation (e.g. you’ve just finished your third martini, or was this the fourth?), then speech problems (e.g. slurred speech, trouble forming sentences, etc) are a very worrying indicator and should be treated as a medical emergency.

- Neurological problems: a bit of a catch-all category, but memory issues, loss of balance, nausea without an obvious alternative cause, are all things that should get checked out immediately just in case.

- Numbness or weakness in the extremities: especially if on one side of the body only, is often caused by the TIA we mentioned earlier. If it’s both sides, then peripheral neuropathy may be the culprit, but having a neurologist take a look at it is a good idea either way.

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Two Things You Can Do To Improve Stroke Survival Chances

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Cherries vs Blueberries – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cherries to blueberries, we picked the blueberries.

Why?

It was close! And blueberries only won by virtue of taking an average value for cherries; we could have (if you’ll pardon the phrase) cherry-picked tart cherries for extra benefits that’d put them ahead of blueberries. That’s how close it is.

In terms of macros, they are almost identical, so nothing to set them apart there.

In the category of vitamins, they are mostly comparable except that blueberries have a lot more vitamin K, and cherries have a lot more vitamin A. Since vitamin K is the vitamin that’s scarcer in general, we’ll call blueberries’ vitamin K content a win.

Blueberries do also have about 6x more vitamin E, with a cup of blueberries containing about 10% of the daily requirement (and cherries containing almost none). Another small win for blueberries.

When it comes to minerals, they are mostly comparable; the largest point of difference is that blueberries contain more manganese while cherries contain more copper; nothing to decide between them here.

We’re down to counting amino acids and antioxidants now, so blueberries have a lot more cystine and tyrosine. They also have slightly more of amino acids that they both only have trace amounts of. And as for antioxidants? Blueberries contain notably more quercetin.

So, blueberries win the day—but if we had specified tart cherries rather than taking an average, they could have come out on top. Enjoy both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Avoiding Razor Burn, Ingrown Hairs & Other Shaving Irritation

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How Does The Video Help?

Dr. Simi Adedeji’s incredibly friendly persona makes this video (below) on avoiding skin irritation, ingrown hairs, and razor burn after shaving a pleasure to watch.

To keep things simple, she breaks down her guide into 10 simple tips.

What Are The 10 Simple Tips?

Tip 1: Prioritize Hydration. Shaving dry hair can lead to increased skin irritation, so Dr. Simi recommends moistening the hair by showering or using a warm, wet towel for 2-4 minutes before getting the razor out.

Tip 2: Avoid Dry Shaving. Dry shaving not only removes hair but can also remove the protective upper layer of skin, which contributes to razor burn. To prevent this, simply use some shaving gel or cream.

Tip 3: Keep Blades New and Sharp. This one’s simple: dull blades can cause skin irritation, whilst a sharp blade ensures a smoother and more comfortable shaving experience.

Tip 4: Avoid Shaving the Same Area Repeatedly. Multiple passes over the same area can remove skin layers, leading to cuts and irritation. Aim to shave each area only once for safer results.

Tip 5: Consider Hair Growth Direction. Shaving in the direction of hair growth results in less irritation, although it may not provide the closest shave.

Tip 6: Apply Gentle Pressure While Shaving. Excessive pressure can lead to cuts and nicks. Use a gentle touch to reduce these risks.

Tip 7: Incorporate Exfoliation into Your Routine. Exfoliating helps release trapped hairs and reduces the risk of ingrown hairs. For those with sensitive skin, it’s recommended to exfoliate either two days before or after shaving.

Tip 8: Avoid Excessive Skin Stretching. Over-stretching the skin during shaving can cause hairs to become ingrown.

Tip 9: Moisturize After Shaving. Shaving can compromise the skin barrier, leading to dryness. Using a moisturizer can be a simple fix.

Tip 10: Regularly Rinse Your Blade. Make sure that, during the shaving process, you are rinsing your blade frequently to remove hair and skin debris. This keeps it sharp during your shave.

If this summary doesn’t do it for you, then you can watch the full video here:

How did you find that video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

Avocado vs Olives – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing avocado to olives, we picked the avocado.

Why?

Both are certainly great! And when it comes to their respective oils, olive oil wins out as it retains many micronutrients that avocado oil loses. But, in their whole form, avocado beats olive:

In terms of macros, avocado has more protein, carbs, fiber, and (healthy) fats. Simply, it’s more nationally-dense than the already nutritionally-dense food that is olives.

When it comes to vitamins, olives are great but avocados really shine; avocado has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7 B9, C, E, K, and choline, while olives boast only more vitamin A.

In the category of minerals, things are closer to even; avocado has more magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc, while olives have a lot more calcium, copper, iron, and selenium. Still, a marginal victory for avocado here.

In short, this is another case of one very healthy food looking bad by standing next to an even better one, so by all means enjoy both—if you’re going to pick one though, avocado is the more nutritionally dense.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Avocado Oil vs Olive Oil – Which is Healthier? ← when made into oils, olive oil wins, but avocado oil is still a good option too

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How Does One Test Acupuncture Against Placebo Anyway?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Pinpointing The Usefulness Of Acupuncture

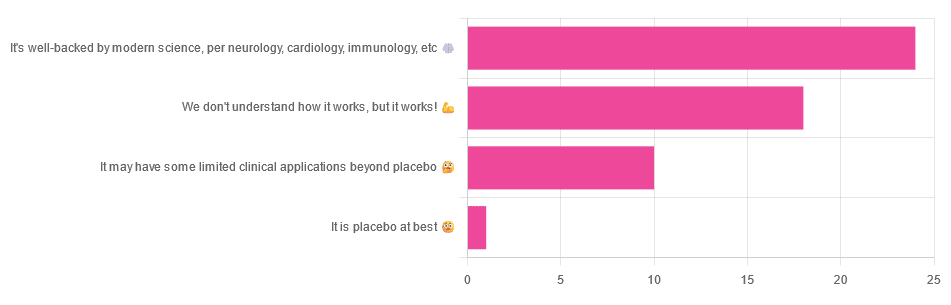

We asked you for your opinions on acupuncture, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of answers:

- A little under half of all respondents voted for “It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc”

- Slightly fewer respondents voted for “We don’t understand how it works, but it works!”

- A little under a fifth of respondents voted for “It may have some limited clinical applications beyond placebo”

- One (1) respondent voted for for “It’s placebo at best”

When we did a main feature about homeopathy, a couple of subscribers wrote to say that they were confused as to what homeopathy was, so this time, we’ll start with a quick definition first.

First, what is acupuncture? For the convenience of a quick definition so that we can move on to the science, let’s borrow from Wikipedia:

❝Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine in which thin needles are inserted into the body.

Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientific knowledge, and it has been characterized as quackery.❞

Now, that’s not a promising start, but we will not be deterred! We will instead examine the science itself, rather than relying on tertiary sources like Wikipedia.

It’s worth noting before we move on, however, that there is vigorous debate behind the scenes of that article. The gist of the argument is:

- On one side: “Acupuncture is not pseudoscience/quackery! This has long been disproved and there are peer-reviewed research papers on the subject.”

- On the other: “Yes, but only in disreputable quack journals created specifically for that purpose”

The latter counterclaim is a) potentially a “no true Scotsman” rhetorical ploy b) potentially true regardless

Some counterclaims exhibit specific sinophobia, per “if the source is Chinese, don’t believe it”. That’s not helpful either.

Well, the waters sure are muddy. Where to begin? Let’s start with a relatively easy one:

It may have some clinical applications beyond placebo: True or False?

True! Admittedly, “may” is doing some of the heavy lifting here, but we’ll take what we can get to get us going.

One of the least controversial uses of acupuncture is to alleviate chronic pain. Dr. Vickers et al, in a study published under the auspices of JAMA (a very respectable journal, and based in the US, not China), found:

❝Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo.

However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture❞

Source: Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis

If you’re feeling sharp today, you may be wondering how the differences are described as “significant” and “relatively modest” in the same text. That’s because these words have different meanings in academic literature:

- Significant = p<0.05, where p is the probability of the achieved results occurring randomly

- Modest = the differences between the test group and the control group were small

In other words, “significant modest differences” means “the sample sizes were large, and the test group reliably got slightly better results than placebo”

We don’t understand how it works, but it works: True or False

Broadly False. When it works, we generally have an idea how.

Placebo is, of course, the main explanation. And even in examples such as the above, how is placebo acupuncture given?

By inserting acupuncture needles off-target rather than in accord with established meridians and points (the lines and dots that, per Traditional Chinese Medicine, indicate the flow of qi, our body’s vital energy, and welling-points of such).

So, if a patient feels that needles are being inserted randomly, they may no longer have the same confidence that they aren’t in the control group receiving placebo, which could explain the “modest” difference, without there being anything “to” acupuncture beyond placebo. After all, placebo works less well if you believe you are only receiving placebo!

Indeed, a (Korean, for the record) group of researchers wrote about this—and how this confounding factor cuts both ways:

❝Given the current research evidence that sham acupuncture can exert not only the originally expected non-specific effects but also sham acupuncture-specific effects, it would be misleading to simply regard sham acupuncture as the same as placebo.

Therefore, researchers should be cautious when using the term sham acupuncture in clinical investigations.❞

Source: Sham Acupuncture Is Not Just a Placebo

It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc: True or False?

False, for the most part.

While yes, the meridians and points of acupuncture charts broadly correspond to nerves and vasculature, there is no evidence that inserting needles into those points does anything for one’s qi, itself a concept that has not made it into Western science—as a unified concept, anyway…

Note that our bodies are indeed full of energy. Electrical energy in our nerves, chemical energy in every living cell, kinetic energy in all our moving parts. Even, to stretch the point a bit, gravitational potential energy based on our mass.

All of these things could broadly be described as qi, if we so wish. Indeed, the ki in the Japanese martial art of aikido is the latter kinds; kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy based on our mass. Same goes, therefore for the ki in kiatsu, a kind of Japanese massage, while the ki in reiki, a Japanese spiritual healing practice, is rather more mystical.

The qi in Chinese qigong is mostly about oxygen, thus indirectly chemical energy, and the electrical energy of the nerves that are receiving oxygenated blood at higher or lower levels.

On the other hand, the efficacy of the use of acupuncture for various kinds of pain is well-enough evidenced. Indeed, even the UK’s famously thrifty NHS (that certainly would not spend money on something it did not find to work) offers it as a complementary therapy for some kinds of pain:

❝Western medical acupuncture (dry needling) is the use of acupuncture following a medical diagnosis. It involves stimulating sensory nerves under the skin and in the muscles.

This results in the body producing natural substances, such as pain-relieving endorphins. It’s likely that these naturally released substances are responsible for the beneficial effects experienced with acupuncture.❞

Source: NHS | Acupuncture

Meanwhile, the NIH’s National Cancer Institute recommends it… But not as a cancer treatment.

Rather, they recommend it as a complementary therapy for pain management, and also against nausea, for which there is also evidence that it can help.

Frustratingly, while they mention that there is lots of evidence for this, they don’t actually link the studies they’re citing, or give enough information to find them. Instead, they say things like “seven randomized clinical trials found that…” and provide links that look reassuring until one finds, upon clicking on them, that it’s just a link to the definition of “randomized clinical trial”:

Source: NIH | Nactional Cancer Institute | Acupuncture (PDQ®)–Patient Version

However, doing our own searches finds many studies (mostly in specialized, potentially biased, journals such as the Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies) finding significant modest outperformance of [what passes for] placebo.

Sometimes, the existence of papers with promising titles, and statements of how acupuncture might work for things other than relief of pain and nausea, hides the fact that the papers themselves do not, in fact, contain any evidence to support the hypothesis. Here’s an example:

❝The underlying mechanisms behind the benefits of acupuncture may be linked with the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (adrenal) axis and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and OPG/RANKL/RANK signaling pathways.

In summary, strong evidence may still come from prospective and well-designed clinical trials to shed light on the potential role of acupuncture in preserving bone loss❞

Source: Acupuncture for Osteoporosis: a Review of Its Clinical and Preclinical Studies

So, here they offered a very sciencey hypothesis, and to support that hypothesis, “strong evidence may still come”.

“We must keep faith” is not usually considered evidence worthy of inclusion in a paper!

PS: the above link is just to the abstract, because the “Full Text” link offered in that abstract leads to a completely unrelated article about HIV/AIDS-related cryptococcosis, in a completely different journal, nothing to do with acupuncture or osteoporosis).

Again, this is not the kind of professionalism we expect from peer-reviewed academic journals.

Bottom line:

Acupuncture reliably performs slightly better than sham acupuncture for the management of pain, and may also help against nausea.

Beyond placebo and the stimulation of endorphin release, there is no consistently reliable evidence that is has any other discernible medical effect by any mechanism known to Western science—though there are plenty of hypotheses.

That said, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and the logistical difficulty of testing acupuncture against placebo makes for slow research. Maybe one day we’ll know more.

For now:

- If you find it helps you: great! Enjoy

- If you think it might help you: try it! By a licensed professional with a good reputation, please.

- If you are not inclined to having needles put in you unnecessarily: skip it! Extant science suggests that at worst, you’ll be missing out on slight relief of pain/nausea.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

10 Tips To Reduce Morning Pain & Stiffness With Arthritis

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Physiotherapist and osteoarthritis specialist Dr. Alyssa Kuhn has professional advice:

Just the tips

We’ll not keep them a mystery; they are:

- Perform movements that target the range of motion in stiff joints, especially in knees and hips, to prevent them from being stuck in limited positions overnight.

- Use relaxation techniques like a hot shower, heating pad, or light reading before bed to reduce muscle tension and stiffness upon waking.

- Manage joint swelling during the day through gentle movement, compression sleeves, and self-massage .

- Maintain a balanced level of activity throughout the day to avoid excessive stiffness from either overactivity or, on the flipside, prolonged inactivity.

- Use pillows to support joints, such as placing one between your knees for hip and knee arthritis, and ensure you have a comfortable pillow for neck support.

- Eat anti-inflammatory foods prioritizing fruits and vegetables to reduce joint stiffness, and avoid foods high in added sugar, trans-fats, and saturated fats.

- Perform simple morning exercises targeting stiff areas to quickly relieve stiffness and ease into your daily routine.

- Engage in strength training exercises 2–3 times per week to build stronger muscles around the joints, which can reduce stiffness and pain.

- Ensure you get 7–8 hours of restful sleep, as poor sleep can increase stiffness and pain sensitivity the next day. 10almonds note: we realize there’s a degree of “catch 22” here, but we’re simply reporting her advice. Of course, do what you can to prioritize being able to get the best quality sleep you can.

- Perform gentle movements or stretches before bed to keep joints limber, focusing on exercises that feel comfortable and soothing.

For more on each of these plus some visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Avoiding/Managing Osteoarthritis

- Avoiding/Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Managing Chronic Pain (Realistically!)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Healing After Loss – by Martha Hickman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mental health is also just health, and this book’s about an underexamined area of mental health. We say “underexamined”, because for something that affects almost everyone sooner or later, there’s not nearly so much science being done about it as other areas of mental health.

This is not a book of science per se, but it is a very useful one. The format is:

Each calendar day of the year, there’s a daily reflection, consisting of:

- A one-liner insight about grief, quoted from somebody

- A page of thoughts about this

- A one-liner summary, often formulated as a piece of advice

The book is not religious in content, though the author does occasionally make reference to God, only in the most abstract way that shouldn’t be offputting to any but the most stridently anti-religious readers.

Bottom line: if this is a subject near to your heart, then you will almost certainly benefit from this daily reader.

Click here to check out Healing After Loss, and indeed heal after loss

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: