‘Sleep tourism’ promises the trip of your dreams. Beyond the hype plus 5 tips for a holiday at home

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Imagine arriving at your hotel after a long flight and being greeted by your own personal sleep butler. They present you with a pillow menu and invite you to a sleep meditation session later that day.

You unpack in a room kitted with an AI-powered smart bed, blackout shades, blue light-blocking glasses and weighted blankets.

Holidays are traditionally for activities or sightseeing – eating Parisian pastry under the Eiffel tower, ice skating at New York City’s Rockefeller Centre, lying by the pool in Bali or sipping limoncello in Sicily. But “sleep tourism” offers vacations for the sole purpose of getting good sleep.

The emerging trend extends out of the global wellness tourism industry – reportedly worth more than US$800 billion globally (A$1.2 trillion) and expected to boom.

Luxurious sleep retreats and sleep suites at hotels are popping up all over the world for tourists to get some much-needed rest, relaxation and recovery. But do you really need to leave home for some shuteye?

Not getting enough

The rise of sleep tourism may be a sign of just how chronically sleep deprived we all are.

In Australia more than one-third of adults are not achieving the recommended 7–9 hours of sleep per night, and the estimated cost of this inadequate sleep is A$45 billion each year.

Inadequate sleep is linked to long-term health problems including poor mental health, heart disease, metabolic disease and deaths from any cause.

Can a fancy hotel give you a better sleep?

Many of the sleep services available in the sleep tourism industry aim to optimise the bedroom for sleep. This is a core component of sleep hygiene – a series of healthy sleep practices that facilitate good sleep including sleeping in a comfortable bedroom with a good mattress and pillow, sleeping in a quiet environment and relaxing before bed.

The more people follow sleep hygiene practices, the better their sleep quality and quantity.

When we are staying in a hotel we are also likely away from any stressors we encounter in everyday life (such as work pressure or caring responsibilities). And we’re away from potential nighttime disruptions to sleep we might experience at home (the construction work next door, restless pets, unsettled children). So regardless of the sleep features hotels offer, it is likely we will experience improved sleep when we are away.

What the science says about catching up on sleep

In the short-term, we can catch up on sleep. This can happen, for example, after a short night of sleep when our brain accumulates “sleep pressure”. This term describes how strong the biological drive for sleep is. More sleep pressure makes it easier to sleep the next night and to sleep for longer.

But while a longer sleep the next night can relieve the sleep pressure, it does not reverse the effects of the short sleep on our brain and body. Every night’s sleep is important for our body to recover and for our brain to process the events of that day. Spending a holiday “catching up” on sleep could help you feel more rested, but it is not a substitute for prioritising regular healthy sleep at home.

All good things, including holidays, must come to an end. Unfortunately the perks of sleep tourism may end too.

Our bodies do not like variability in the time of day that we sleep. The most common example of this is called “social jet lag”, where weekday sleep (getting up early to get to work or school) is vastly different to weekend sleep (late nights and sleep ins). This can result in a sleepy, grouchy start to the week on Monday. Sleep tourism may be similar, if you do not come back home with the intention to prioritise sleep.

So we should be mindful that as well as sleeping well on holiday, it is important to optimise conditions at home to get consistent, adequate sleep every night.

5 tips for having a sleep holiday at home

An AI-powered mattress and a sleep butler at home might be the dream. But these features are not the only way we can optimise our sleep environment and give ourselves the best chance to get a good night’s sleep. Here are five ideas to start the night right:

1. avoid bright artificial light in the evening (such as bright overhead lights, phones, laptops)

2. make your bed as comfortable as possible with fresh pillows and a supportive mattress

3. use black-out window coverings and maintain a cool room temperature for the ideal sleeping environment

4. establish an evening wind-down routine, such as a warm shower and reading a book before bed or even a “sleepy girl mocktail”

5. use consistency as the key to a good sleep routine. Aim for a similar bedtime and wake time – even on weekends.

Charlotte Gupta, Senior postdoctoral research fellow, Appleton Institute, HealthWise research group, CQUniversity Australia and Dean J. Miller, Adjunct Research Fellow, Appleton Institute of Behavioural Science, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Sugary Food That Lowers Blood Sugars

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Loved the article on goji berries! I read they are good for blood sugars, is that true despite the sugar content?❞

Most berries are! Fruits that are high in polyphenols (even if they’re high in sugar), like berries, have a considerable net positive impact on glycemic health:

- Polyphenols and Glycemic Control

- Polyphenols and their effects on diabetes management: A review

- Dietary polyphenols as antidiabetic agents: Advances and opportunities

And more specifically:

Dietary berries, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: an overview of human feeding trials

Read more: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

As for goji berries specifically, they’re very high indeed in polyphenols, and also have a hypoglycemic effect, i.e., they lower blood sugar levels (and as a bonus, increases HDL (“good” cholesterol) levels too, but that’s not the topic here):

❝The results of our study indicated a remarkable protective effect of LBP in patients with type 2 diabetes. Serum glucose was found to be significantly decreased and insulinogenic index increased during OMTT after 3 months administration of LBP. LBP also increased HDL levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. It showed more obvious hypoglycemic efficacy for those people who did not take any hypoglycemic medicine compared to patients taking hypoglycemic medicines. This study showed LBP to be a good potential treatment aided-agent for type 2 diabetes.❞

- LBP = Lycium barbarum polysaccharide, i.e. polysaccharide in/from goji berries

- OMTT = Oral metabolic tolerance test, a test of how well the blood sugars avoid spiking after a meal

For more about goji berries (and also where to get them), for reference our previous article is at:

Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

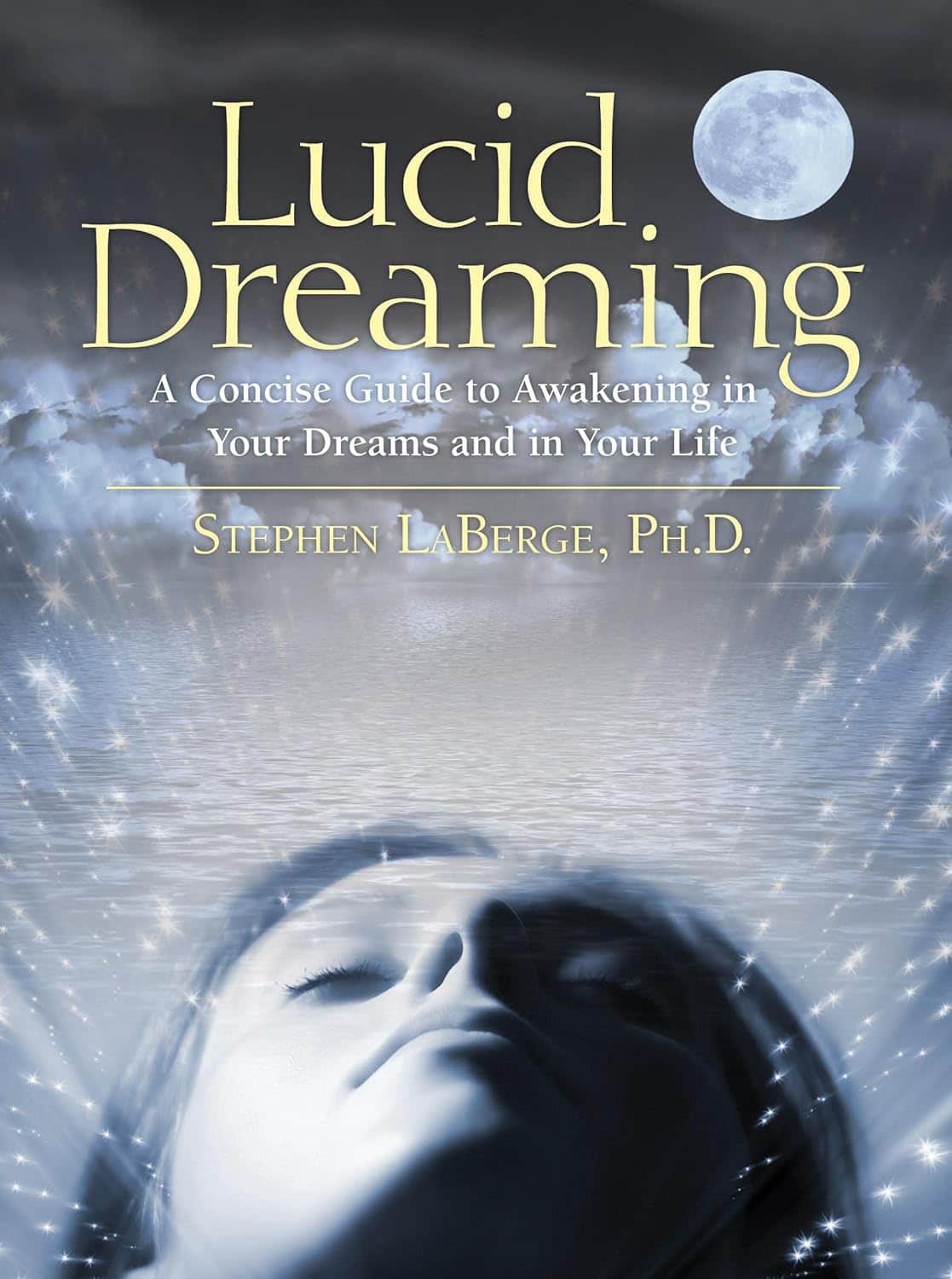

Lucid Dreaming – by Stephen LaBerge Ph.D.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For any unfamiliar: lucid dreaming means being aware that one is dreaming, while dreaming, and exercising a degree of control over the dream. Superficially, this is fun. But if one really wants to go deeper into it, it can be a lot more:

Dr. Stephen LaBerge takes a science-based approach to lucid dreaming, and in this work provides not only step-by-step instructions of several ways of inducing lucid dreaming, but also, opens the reader’s mind to things that can be done there beyond the merely recreational:

In lucid dreams, he argues and illustrates, it’s possible to talk to parts of one’s own subconscious (Inception, anyone? Yes, this book came first) and get quite an amount of self-therapy done. And that hobby you wish you had more time to practice? The possibilities just became limitless. And who wouldn’t want that?

Share This Post

-

Proteins Of The Week

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This week’s news round-up is, entirely by chance, somewhat protein-centric in one form or another. So, check out the bad, the very bad, the mostly good, the inconvenient, and the worst:

Mediterranean diet vs the menopause

Researchers looked at hundreds of women with an average age of 51, and took note of their dietary habits vs their menopause symptoms. Most of them were consuming soft drinks and red meat, and not good in terms of meeting the recommendations for key food groups including vegetables, legumes, fruit, fish and nuts, and there was an association between greater adherence to Mediterranean diet principles, and better health.

Read in full: Fewer soft drinks and less red meat may ease menopause symptoms: Study

Related: Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet

Listeria in meat

This one’s not a study, but it is relevant important news. The headline pretty much says it all, so if you don’t eat meat, this isn’t one you need to worry about any further than that. If you do eat meat, though, you might want to check out the below article to find out whether the meat you eat might be carrying listeria:

Read in full: Almost 10 million pounds of meat recalled due to Listeria danger

Related: Frozen/Thawed/Refrozen Meat: How Much Is Safety, And How Much Is Taste?

Brawn and brain?

A study looked at cognitively healthy older adults (of whom, 57% women), and found an association between their muscle strength and their psychological wellbeing. Note that when we said “cognitively healthy”, this means being free from dementia etc—not necessarily psychologically health in all respects, such as also being free from depression and enjoying good self-esteem.

Read in full: Study links muscle strength and mental health in older adults

Related: Staying Strong: Tips To Prevent Muscle Loss With Age

The protein that blocks bone formation

This one’s more clinical but definitely of interest to any with osteoporosis or at high risk of osteoporosis. Researchers identified a specific protein that blocks osteoblast function, thus more of this protein means less bone production. Currently, this is not something that we as individuals can do anything about at home, but it is promising for future osteoporosis meds development.

Read in full: Protein blocking bone development could hold clues for future osteoporosis treatment

Related: Which Osteoporosis Medication, If Any, Is Right For You?

Rabies risk

People associate rabies with “rabid dogs”, but the biggest rabies threat is actually bats, and they don’t even need to necessarily bite you to confer the disease (it suffices to have licked the skin, for instance—and bats are basically sky-puppies who will lick anything). Because rabies has a 100% fatality rate in unvaccinated humans, this is very serious. This means that if you wake up and there’s a bat in the house, it doesn’t matter if it hasn’t bitten anyone; get thee to a hospital (where you can get the vaccine before the disease takes hold; this will still be very unpleasant but you’ll probably survive so long as you get the vaccine in time).

Read in full: What to know about bats and rabies

Related: Dodging Dengue In The US ← much less serious than rabies, but still not to be trifled with—particularly noteworthy if you’re in an area currently affected by floodwaters or even just unusually heavy rain, by the way, as this will leave standing water in which mosquitos breed.

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Circadian Rhythm: Far More Than Most People Know

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Circadian Rhythm: Far More Than Most People Know

This is Dr. Satchidananda (Satchin) Panda, the scientist behind the discovery of the blue-light sensing cell type in the retina, and the many things it affects. But, he’s discovered more…

First, what you probably know (with a little more science)

Dr. Panda discovered that melanopsin, a photopigment, is “the primary candidate for photoreceptor-mediated entrainment”.

To put that in lay terms, it’s the brain’s go-to for knowing approximately what time of day or night it is, according to how much light there is (or isn’t), and how long it has (or hasn’t) been there.

But… the brain’s “go-to” isn’t the only method. By creating mice without melanopsin, he was able to find that they still keep a circadian rhythm, even in complete darkness:

Melanopsin (Opn4) Requirement for Normal Light-Induced Circadian Phase Shifting

In other words, it was a helpful, but not completely necessary, means of keeping a circadian rhythm.

So… What else is going on?

Dr. Panda and his team did a lot of science that is well beyond the scope of this main feature, but to give you an idea:

- With jargon: it explored the mechanisms and transcription translation negative feedback loops that regulate chronobiological processes, such as a histone lysine demathlyase 1a (JARID1a) that enhances Clock-Bmal1 transcription, and then used assorted genomic techniques to develop a model for how JARID1a works to moderate the level of Per transcription by regulating the transition between its repression and activation, and discovered that this heavily centered on hepatic gluconeogenesis and glucose homeostasis, facilitated by the protein cryptochrome regulating the fasting signal that occurs when glucagon binds to a G-protein coupled receptor, triggering CREB activation.

- Without jargon: a special protein tells our body how to respond to eating/fasting at different times of day—and conversely, certain physiological responses triggered by eating/fasting help us know what time of day it is.

- Simplest: our body keeps on its best cycle if we eat at the same time every day

This is important, because our circadian rhythm matters for a lot more than sleeping/waking! Take hormones, for example:

- Obvious hormones: testosterone and estrogen peak in the mornings around 9am, progesterone peaks between 10pm and 2am

- Forgotten hormones: cortisol peaks in the morning around 8:30am, melatonin peaks between 10pm and 2am

- More hormones: ghrelin (hunger hormone) peaks around 10am, leptin (satiety hormone) peaks 20 minutes after eating a certain amount of satiety-triggering food (protein does this most quickly), insulin is heavily tied to carbohydrate intake, but will still peak and trough according to when the body expects food.

What does this mean for us in practical terms?

For a start, it means that intermittent fasting can help guard against metabolic and related diseases (including inflammation, and thus also cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and more) a lot more if we practice it with our circadian rhythm in mind.

So that “8-hour window” for eating, that many intermittent fasting practitioners adhere to, is going to do much, much better if it’s 10am to 6pm, rather than, say, 4pm to midnight.

Additionally, Dr. Panda and his team found that a 12-hour eating window wasn’t sufficient to help significantly.

Some other take-aways:

- For reasons beyond the scope of this article, it’s good to exercise a) early b) before eating, so getting in some exercise between 8.30am and 10am is ideal

- It also means it’s beneficial to “front-load” eating, so a large breakfast at 10am, and smaller meals/snacks afterwards, is best.

- It also means that getting sunlight (even if cloud-covered) around 8.30am helps guard against metabolic disorders a lot, since the light remains the body’s go-to way of knowing the time.

- We realize that sunlight is not available at 8.30am at all latitudes at all times of year. Artificial is next-best.

- It also means sexual desire will typically peak in men in the mornings (per testosterone) and women in the evenings (per progesterone), but this is just an interesting bit of trivia, and not so relevant to metabolic health

What to do next…

Want to stabilize your own circadian rhythm in the best way, and also help Dr. Panda with his research?

His team’s (free!) app, “My Circadian Clock”, can help you track and organize all of the body’s measurable-by-you circadian events, and, if you give permission, will contribute to what will be the largest-yet human study into the topics covered today, to refine the conclusions and learn more about what works best.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

A Supplement To Rival St. John’s Wort Against Depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Do You Feel The SAMe?

S-Adeonsyl-L-Methionone (SAMe) is a chemical found naturally in the body, and/but enjoyed widely as a supplement. The main reasons people take it are:

- Improve mood (antidepressant effect)

- Improve joints (reduce osteoarthritis symptoms)

- Improve liver (detoxifying effect)

Let’s see what the science says for each of those claims…

Does it improve mood?

It seems to perform comparably to St. John’s Wort (which is good; it performs comparably to Prozac).

Best of all, it does this with fewer contraindications (St. John’s Wort has so many contraindications).

Here’s how they stack up:

This looks very promising, though it’d be nice to see a larger body of research, to be sure.

Does it reduce osteoarthritis symptoms?

The good news: it performs comparably to ibuprofen, with fewer side effects!

The bad news: it also performs comparably to placebo!

Read into that what you will about ibuprofen’s usefulness vs OA symptoms.

Read all about it:

S-Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip

If you were hoping for something for OA or similar symptoms, you might like our previous main features:

- Avoiding/Managing Osteoarthritis

- Managing Chronic Pain (Realistically!)

- The 7 Approaches To Pain Management

- (Science-Based) Alternative Pain Relief

Does it help against liver disease?

According to adverts for SAMe: absolutely!

According to science: we don’t know

The science for this is so weak that it’d be unworthy of mention if it weren’t for the fact that SAMe is so widely sold as good against hepatotoxicity.

To be clear: maybe it really is great! Science hasn’t yet disproved its usefulness either.

It is popularly assumed to be beneficial due to there being an association between lower levels of SAMe in the body (remember, it is also produced inside our bodies) and development of liver disease, especially cholestasis.

Here’s an example of what pretty much every study we found was like (inconclusive research based mostly on mice):

S-adenosylmethionine in liver health, injury, and cancer

For other options for liver health, consider:

Is it safe?

Safety trials have been done ranging from 3 months to 2 years, with no serious side effects coming to light. So, it appears quite safe.

That said, as with anything, there are contraindications, such as:

- if you have bipolar disorder, skip this unless directed by your health care provider, because it may worsen the symptoms of mania

- if you are on SSRIs or other serotonergic drugs, it may interact with those

- if you are immunocompromised, you might want to skip it can increase the risk of P. carinii growth in such cases

As always, do speak with your doctor/pharmacist for personalized advice.

Summary

SAMe’s evidence-based qualities seem to stack up as follows:

- Against depression: good

- Against osteoarthritis: weak

- Against liver disease: unknown

As for safety, it has been found quite safe for most people.

Where can I get it?

We don’t sell it, but here is an example product on Amazon, for your convenience

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Cashews vs Peanuts – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cashews to peanuts, we picked the peanuts.

Why?

Another one for “that which is more expensive is not necessarily the healthier”! Although, certainly both are good:

In terms of macros, cashews have about 2x the carbs while peanuts have a little more (healthy!) fat and more than 2x the fiber, meaning that peanuts also enjoy the lower glycemic index. All in all, a fair win for peanuts here.

When it comes to vitamins, cashews have more of vitamins B6 and K, while peanuts have a lot more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B7, B9, and E. Another easy win for peanuts.

In the category of minerals; cashews have more copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, and selenium, while peanuts have more calcium, manganese, and potassium. A win for cashews, this time.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall win for peanuts, but (assuming you are not allergic) enjoy either or both! In fact, enjoying both is best; diversity is good.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: