As the U.S. Struggles With a Stillbirth Crisis, Australia Offers a Model for How to Do Better

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Series: Stillbirths:When Babies Die Before Taking Their First Breath

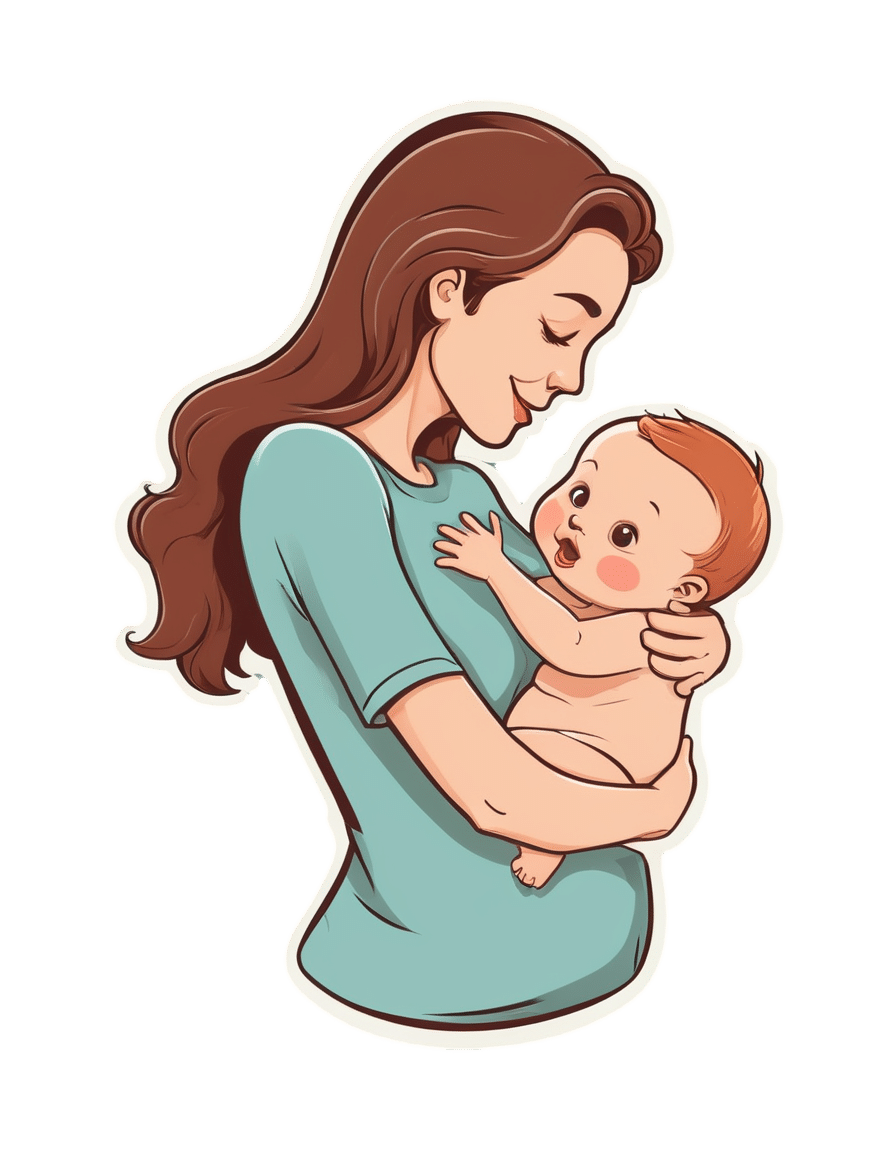

The U.S. has not prioritized stillbirth prevention, and American parents are losing babies even as other countries make larger strides to reduce deaths late in pregnancy.

The stillbirth of her daughter in 1999 cleaved Kristina Keneally’s life into a before and an after. It later became a catalyst for transforming how an entire country approaches stillbirths.

In a world where preventing stillbirths is typically far down the list of health care priorities, Australia — where Keneally was elected as a senator — has emerged as a global leader in the effort to lower the number of babies that die before taking their first breaths. Stillbirth prevention is embedded in the nation’s health care system, supported by its doctors, midwives and nurses, and touted by its politicians.

In 2017, funding from the Australian government established a groundbreaking center for research into stillbirths. The next year, its Senate established a committee on stillbirth research and education. By 2020, the country had adopted a national stillbirth plan, which combines the efforts of health care providers and researchers, bereaved families and advocacy groups, and lawmakers and government officials, all in the name of reducing stillbirths and supporting families. As part of that plan, researchers and advocates teamed up to launch a public awareness campaign. All told, the government has invested more than $40 million.

Meanwhile, the United States, which has a far larger population, has no national stillbirth plan, no public awareness campaign and no government-funded stillbirth research center. Indeed, the U.S. has long lagged behind Australia and other wealthy countries in a crucial measure: how fast the stillbirth rate drops each year.

According to the latest UNICEF report, the U.S. was worse than 151 countries in reducing its stillbirth rate between 2000 and 2021, cutting it by just 0.9%. That figure lands the U.S. in the company of South Sudan in Africa and doing slightly better than Turkmenistan in central Asia. During that period, Australia’s reduction rate was more than double that.

Definitions of stillbirth vary by country, and though both Australia and the U.S. mark stillbirths as the death of a fetus at 20 weeks or more of pregnancy, to fairly compare countries globally, international standards call for the use of the World Health Organization definition that defines stillbirth as a loss after 28 weeks. That puts the U.S. stillbirth rate in 2021 at 2.7 per 1,000 total births, compared with 2.4 in Australia the same year.

Every year in the United States, more than 20,000 pregnancies end in a stillbirth. Each day, roughly 60 babies are stillborn. Australia experiences six stillbirths a day.

Over the past two years, ProPublica has revealed systemic failures at the federal and local levels, including not prioritizing research, awareness and data collection, conducting too few autopsies after stillbirths and doing little to combat stark racial disparities. And while efforts are starting to surface in the U.S. — including two stillbirth-prevention bills that are pending in Congress — they lack the scope and urgency seen in Australia.

“If you ask which parts of the work in Australia can be done in or should be done in the U.S., the answer is all of it,” said Susannah Hopkins Leisher, a stillbirth parent, epidemiologist and assistant professor in the stillbirth research program at the University of Utah Health. “There’s no physical reason why we cannot do exactly what Australia has done.”

Australia’s goal, which has been complicated by the pandemic, is to, by 2025, reduce the country’s rate of stillbirths after 28 weeks by 20% from its 2020 rate. The national plan laid out the target, and it is up to each jurisdiction to determine how to implement it based on their local needs.

The most significant development came in 2019, when the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence — the headquarters for Australia’s stillbirth-prevention efforts — launched the core of its strategy, a checklist of five evidence-based priorities known as the Safer Baby Bundle. They include supporting pregnant patients to stop smoking; regular monitoring for signs that the fetus is not growing as expected, which is known as fetal growth restriction; explaining the importance of acting quickly if fetal movement changes or decreases; advising pregnant patients to go to sleep on their side after 28 weeks; and encouraging patients to talk to their doctors about when to deliver because in some cases that may be before their due date.

Officials estimate that at least half of all births in the country are covered by maternity services that have adopted the bundle, which focuses on preventing stillbirths after 28 weeks.

“These are babies whose lives you would expect to save because they would survive if they were born alive,” said Dr. David Ellwood, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Griffith University, director of maternal-fetal medicine at Gold Coast University Hospital and a co-director of the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence.

Australia wasn’t always a leader in stillbirth prevention.

In 2000, when the stillbirth rate in the U.S. was 3.3 per 1,000 total births, Australia’s was 3.7. A group of doctors, midwives and parents recognized the need to do more and began working on improving their data classification and collection to better understand the problem areas. By 2014, Australia published its first in-depth national report on stillbirth. Two years later, the medical journal The Lancet published the second report in a landmark series on stillbirths, and Australian researchers applied for the first grant from the government to create the stillbirth research center.

But full federal buy-in remained elusive.

As parent advocates, researchers, doctors and midwives worked to gain national support, they didn’t yet know they would find a champion in Keneally.

Keneally’s improbable journey began when she was born in Nevada to an American father and Australian mother. She grew up in Ohio, graduating from the University of Dayton before meeting the man who would become her husband and moving to Australia.

When she learned that her daughter, who she named Caroline, would be stillborn, she remembers thinking, “I’m smart. I’m educated. How did I let this happen? And why did nobody tell me this was a possible outcome?”

A few years later, in 2003, Keneally decided to enter politics. She was elected to the lower house of state parliament in New South Wales, of which Sydney is the capital. In Australia, newly elected members are expected to give a “first speech.” She was able to get through just one sentence about Caroline before starting to tear up.

As a legislator, Keneally didn’t think of tackling stillbirth as part of her job. There wasn’t any public discourse about preventing stillbirths or supporting families who’d had one. When Caroline was born still, all Keneally got was a book titled “When a Baby Dies.”

In 2009, Keneally became New South Wales’ first woman premier, a role similar to that of an American governor. Another woman who had suffered her own stillbirth and was starting a stillbirth foundation learned of Keneally’s experience. She wrote to Keneally and asked the premier to be the foundation’s patron.

What’s the point of being the first female premier, Keneally thought, if I can’t support this group?

Like the U.S., Australia had previously launched an awareness campaign that contributed to a staggering reduction in sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS. But there was no similar push for stillbirths.

“If we can figure out ways to reduce SIDS,” Keneally said, “surely it’s not beyond us to figure out ways to reduce stillbirth.”

She lost her seat after two years and took a break from politics, only to return six years later. In 2018, she was selected to serve as a senator at Australia’s federal level.

Keneally saw this as her second chance to fight for stillbirth prevention. In the short period between her election and her inaugural speech, she had put everything in place for a Senate inquiry into stillbirth.

In her address, Keneally declared stillbirth a national public health crisis. This time, she spoke at length about Caroline.

“When it comes to stillbirth prevention,” she said, “there are things that we know that we’re not telling parents, and there are things we don’t know, but we could, if we changed how we collected data and how we funded research.”

The day of her speech, March 27, 2018, she and her fellow senators established the Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education.

Things moved quickly over the next nine months. Keneally and other lawmakers traveled the country holding hearings, listening to testimony from grieving parents and writing up their findings in a report released that December.

“The culture of silence around stillbirth means that parents and families who experience it are less likely to be prepared to deal with the personal, social and financial consequences,” the report said. “This failure to regard stillbirth as a public health issue also has significant consequences for the level of funding available for research and education, and for public awareness of the social and economic costs to the community as a whole.”

It would be easy to swap the U.S. for Australia in many places throughout the report. Women of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds experienced double the rate of stillbirth of other Australian women; Black women in America are more than twice as likely as white women to have a stillbirth. Both countries faced a lack of coordinated research and corresponding funding, low autopsy rates following a stillbirth and poor public awareness of the problem.

The day after the report’s release, the Australian government announced that it would develop a national plan and pledged $7.2 million in funding for prevention. Nearly half was to go to education and awareness programs for women and their health care providers.

In the following months, government officials rolled out the Safer Baby Bundle and pledged another $26 million to support parents’ mental health after a loss.

Many in Australia see Keneally’s first speech as senator, in 2018, as the turning point for the country’s fight for stillbirth prevention. Her words forced the federal government to acknowledge the stillbirth crisis and launch the national action plan with bipartisan support.

Australia’s assistant minister for health and aged care, Ged Kearney, cited Keneally’s speech in an email to ProPublica where she noted that Australia has become a world leader in stillbirth awareness, prevention and supporting families after a loss.

“Kristina highlighted the power of women telling their story for positive change,” Kearney said, adding, “As a Labor Senator Kristina Keneally bravely shared her deeply personal story of her daughter Caroline who was stillborn in 1999. Like so many mothers, she helped pave the way for creating a more compassionate and inclusive society.”

Keneally, who is now CEO of Sydney Children’s Hospitals Foundation, said the number of stillbirths a day in Australia spurred the movement for change.

“Six babies a day,” Keneally said. “Once you hear that fact, you can’t unhear it.”

Australia’s leading stillbirth experts watched closely as the country moved closer to a unified effort. This was the moment for which they had been waiting.

“We had all the information needed, but that’s really what made it happen.” said Vicki Flenady, a perinatal epidemiologist, co-director of the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence based at the Mater Research Institute at the University of Queensland, and a lead author on The Lancet’s stillbirth series. “I don’t think there’s a person who could dispute that.”

Flenady and her co-director Ellwood had spent more than two decades focused on stillbirths. After establishing the center in 2017, they were now able to expand their team. As part of their work with the International Stillbirth Alliance, they reached out to other countries with a track record of innovation and evidence-based research: the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Ireland. They modeled the Safer Baby Bundle after a similar one in the U.K., though they added some elements.

In 2019, the state of Victoria, home to Melbourne, was the first to implement the Safer Baby Bundle. But 10 months into the program, the effort had to be paused for several months because of the pandemic, which forced other states to cancel their launches altogether.

“COVID was a major disruption. We stopped and started,” Flenady said.

Still, between 2019 and 2021, participating hospitals across Victoria were able to reduce their stillbirth rate by 21%. That improvement has yet to be seen at the national level.

A number of areas are still working on implementing the bundle. Westmead Hospital, one of Australia’s largest hospitals, planned to wrap that phase up last month. Like many hospitals, Westmead prominently displays the bundle’s key messages in the colorful posters and flyers hanging in patient rooms and in the hallways. They include easy-to-understand slogans such as, “Big or small. Your baby’s growth matters,” and, “Sleep on your side when baby’s inside.”

As patients at Westmead wait for their names to be called, a TV in the waiting room plays a video on stillbirth prevention, highlighting the importance of fetal movement. If a patient is concerned their baby’s movements have slowed down, they are instructed to come in to be seen within two hours. The patient’s chart gets a colorful sticker with a 16-point checklist of stillbirth risk factors.

Susan Heath, a senior clinical midwife at Westmead, came up with the idea for the stickers. Her office is tucked inside the hospital’s maternity wing, down a maze of hallways. As she makes the familiar walk to her desk, with her faded hospital badge bouncing against her navy blue scrubs, it’s clear she is a woman on a mission. The bundle gives doctors and midwives structure and uniform guidance, she said, and takes stillbirth out of the shadows. She reminds her staff of how making the practices a routine part of their job has the power to change their patients’ lives.

“You’re trying,” she said, “to help them prevent having the worst day of their life.”

Christine Andrews, a senior researcher at the Stillbirth Centre who is leading an evaluation of the program’s effectiveness, said the national stillbirth rate beyond 28 weeks has continued to slowly improve.

“It is going to take a while until we see the stillbirth rate across the whole entire country go down,” Andrews said. “We are anticipating that we’re going to start to see a shift in that rate soon.”

As officials wait to receive and standardize the data from hospitals and states, they are encouraged by a number of indicators.

For example, several states are reporting increases in the detection of babies that aren’t growing as they should, a major factor in many late-gestation stillbirths. Many also have seen an increase in the number of pregnant patients who stopped smoking. Health care providers also are more consistently offering post-stillbirth investigations, such as autopsies.

In addition to the Safer Baby Bundle, the national plan also calls for raising awareness and reducing racial disparities. The improvements it recommends for bereavement care are already gaining global attention.

To fulfill those directives, Australia has launched a “Still Six Lives” public awareness campaign, has implemented a national stillbirth clinical care standard and has spent two years developing a culturally inclusive version of the Safer Baby Bundle for First Nations, migrant and refugee communities. Those resources, which were recently released, incorporated cultural traditions and used terms like Stronger Bubba Born for the bundle and “sorry business babies,” which is how some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women refer to stillbirth. There are also audio versions for those who can’t or prefer not to read the information.

In May, nearly 50 people from the state of Queensland met in a large hotel conference room. Midwives, doctors and nurses sat at round tables with government officials, hospital administrators and maternal and infant health advocates. Some even wore their bright blue Safer Baby T-shirts.

One by one, they discussed their experiences implementing the Safer Baby Bundle. One midwifery group was able to get more than a third of its patients to stop smoking between their first visit and giving birth.

Officials from a hospital in one of the fastest-growing areas in the state discussed how they carefully monitored for fetal growth restriction.

And staff from another hospital, which serves many low-income and immigrant patients, described how 97% of pregnant patients who said their baby’s movements had decreased were seen for additional monitoring within two hours of voicing their concern.

As the midwives, nurses and doctors ticked off the progress they were seeing, they also discussed the fear of unintended consequences: higher rates of premature births or increased admissions to neonatal intensive care units. But neither, they said, has materialized.

“The bundle isn’t causing any harm and may be improving other outcomes, like reducing early-term birth,” Flenady said. “I think it really shows a lot of positive impact.”

As far behind as the U.S. is in prioritizing stillbirth prevention, there is still hope.

Dr. Bob Silver, who co-authored a study that estimated that nearly 1 in 4 stillbirths are potentially preventable, has looked to the international community as a model. Now, he and Leisher — the University of Utah epidemiologist and stillbirth parent — are working to create one of the first stillbirth research and prevention centers in the U.S. in partnership with stillbirth leaders from Australia and other countries. They hope to launch next year.

“There’s no question that Australia has done a better job than we have,” said Silver, who is also chair of the University of Utah Health obstetrics and gynecology department. “Part of it is just highlighting it and paying attention to it.”

It’s hard to know what parts of Australia’s strategy are making a difference — the bundle as a whole, just certain elements of it, the increased stillbirth awareness across the country, or some combination of those things. Not every component has been proven to decrease stillbirth.

The lack of U.S. research on the issue has made some cautious to adopt the bundle, Silver said, but it is clear the U.S. can and should do more.

There comes a point when an issue is so critical, Silver said, that people have to do the best they can with the information that they have. The U.S. has done that with other problems, such as maternal mortality, he said, though many of the tactics used to combat that problem have not been proven scientifically.

“But we’ve decided this problem is so bad, we’re going to try the things that we think are most likely to be helpful,” Silver said.

After more than 30 years of working on stillbirth prevention, Silver said the U.S. may be at a turning point. Parents’ voices are getting louder and starting to reach lawmakers. More doctors are affirming that stillbirths are not inevitable. And pressure is mounting on federal institutions to do more.

Of the two stillbirth prevention bills in Congress, one already sailed through the Senate. The second bill, the Stillbirth Health Improvement and Education for Autumn Act, includes features that also appeared in Australia’s plan, such as improving data, increasing awareness and providing support for autopsies.

And after many years, the National Institutes of Health has turned its focus back to stillbirths. In March, it released a report with a series of recommendations to reduce the nation’s stillbirth rate that mirror ProPublica’s reporting about some of the causes of the crisis. Since then, it has launched additional groups to begin to tackle three critical angles: prevention, data and bereavement. Silver co-chairs the prevention group.

In November, more than 100 doctors, parents and advocates gathered for a symposium in New York City to discuss everything from improving bereavement care in the U.S to tackling racial disparities in stillbirth. In 2022, after taking a page out of the U.K.’s book, the city’s Mount Sinai Hospital opened the first Rainbow Clinic in the U.S., which employs specific protocols to care for people who have had a stillbirth.

But given the financial resources in the U.S. and the academic capacity at American universities and research institutions, Leisher and others said federal and state governments aren’t doing nearly enough.

“The U.S. is not pulling its weight in relation either to our burden or to the resources that we have at our disposal,” she said. “We’ve got a lot of babies dying, and we’ve got a really bad imbalance of who those babies are as well. And yet we look at a country with a much smaller number of stillbirths who is leading the world.”

“We can do more. Much more. We’re just not,” she added. “It’s unacceptable.”

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Your Brain on Art – by Susan Magsamen & Ivy Ross

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The notion of art therapy is popularly considered a little wishy-washy. As it turns out, however, there are thousands of studies showing its effectiveness.

Nor is this just a matter of self-expression. As authors Magsamen and Ross explore, different kinds of engagement with art can convey different benefits.

That’s one of the greatest strengths of this book: “this form of engagement with art will give these benefits, according to these studies”

With benefits ranging from reducing stress and anxiety, to overcoming psychological trauma or physical pain, there’s a lot to be said for art!

And because the book covers many kinds of art, if you can’t imagine yourself taking paintbrush to canvas, that’s fine too. We learn of the very specific cognitive benefits of coloring in mandalas (yes, really), of sculpting something terrible in clay, or even just of repainting the kitchen, and more. Each thing has its set of benefits.

The book’s main goal is to encourage the reader to cultivate what the authors call an aesthetic mindset, which involves four key attributes:

- a high level of curiosity

- a love of playful, open-ended exploration

- a keen sensory awareness

- a drive to engage in creative activities

And, that latter? It’s as a maker and/or a beholder. We learn about what we can gain just by engaging with art that someone else made, too.

Bottom line: come for the evidence-based cognitive benefits; stay for the childlike wonder of the universe. If you already love art, or have thought it’s just “not for you”, then this book is for you.

Click here to check out Your Brain On Art, and open up whole new worlds of experience!

Share This Post

-

A Fresh Take On Hypothyroidism

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Three Rs To Boost Thyroid-Related Energy Levels

This is Dr. Izabella Wentz. She’s a doctor of pharmacology, and after her own diagnosis with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, she has taken it up as her personal goal to educate others on managing hypothyroidism.

Dr. Wentz is also trained in functional medicine through The Institute for Functional Medicine, Kalish Functional Medicine, and the American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine. She is a Fellow of the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists, and holds certifications in Medication Therapy Management as well as Advanced Diabetes Care through the American Pharmacists Association. In 2013, she received the Excellence in Innovation Award from the Illinois Pharmacists Association.

Dr. Wentz’s mission

Dr. Wentz was disenchanted by the general medical response to hypothyroidism in three main ways. She tells us:

- Thyroid patients are not diagnosed appropriately.

- For this, she criticises over-reliance on TSH tests that aren’t a reliable marker of thyroid function, especially if you have Hashimoto’s.

- Patients should be better optimized on their medications.

- For this, she criticizes many prescribed drugs that are actually pro-drugs*, that don’t get converted adequately if you have an underactive thyroid.

- Lifestyle interventions are often ignored by mainstream medicine.

- Medicines are great; they truly are. But medicating without adjusting lifestyle can be like painting over the cracks in a crumbling building.

*a “pro-drug” is what it’s called when the drug we take is not the actual drug the body needs, but is a precursor that will get converted to that actual drug we need, inside our body—usually by the liver, but not always. An example in this case is T4, which by definition is a pro-drug and won’t always get correctly converted to the T3 that a thyroid patient needs.

Well that does indeed sound worthy of criticism. But what does she advise instead?

First, she recommends a different diagnostic tool

Instead of (or at least, in addition to) TSH tests, she advises to ask for TPO tests (thyroid peroxidase), and a test for Tg antibodies (thyroglobulin). She says these are elevated for many years before a change in TSH is seen.

Next, identify the root cause and triggers

These can differ from person to person, but in countries that add iodine to salt, that’s often a big factor. And while gluten may or may not be a factor, there’s a strong correlation between celiac disease and Hashimoto’s disease, so it is worth checking too. Same goes for lactose.

By “checking”, here we mean testing eliminating it and seeing whether it makes a difference to energy levels—this can be slow, though, so give it time! It is best to do this under the guidance of a specialist if you can, of course.

Next, get to work on repairing your insides.

Remember we said “this can be slow”? It’s because your insides won’t necessarily bounce back immediately from whatever they’ve been suffering from for what’s likely many years. But, better late than never, and the time will pass anyway, so might as well get going on it.

For this, she recommends a gut-healthy diet with specific dietary interventions for hypothyroidism. Rather than repeat ourselves unduly here, we’ll link to a couple of previous articles of ours, as her recommendations match these:

She also recommends regular blood testing to see if you need supplementary TSH, TPO antibodies, and T3 and T4 hormones—as well as vitamin B12.

Short version

After diagnosis, she recommends the three Rs:

- Remove the causes and triggers of your hypothyroidism, so far as possible

- Repair the damage caused to your body, especially your gut

- Replace the thyroid hormones and related things in which your body has become deficient

Learn more

If you’d like to learn more about this, she offers a resource page, with resources ranging from on-screen information, to books you can get, to links to hook you up with blood tests if you need them, as well as recommended supplements to consider.

She also has a blog, which has an interesting relevant article added weekly.

Enjoy, and take care of yourself!

Share This Post

- Thyroid patients are not diagnosed appropriately.

-

Body Sculpting with Kettlebells for Women – by Lorna Kleidman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For those of us who are more often lifting groceries or pots and pans than bodybuilding trophies, kettlebells provide a way of training functional strength. This book does (as per the title) offer both sides of things—the body sculpting, and thebody maintenance free from pain and injury.

Kleidman first explains the basics of kettlebell training, and how to get the most from one’s workouts, before discussing what kinds of exercises are best for which benefits, and finally moving on to provide full exercise programs.

The exercise programs themselves are fairly comprehensive without being unduly detailed, and give a week-by-week plan for getting your body to where you want it to be.

The style is fairly personal and relaxed, while keeping things quite clear—the photographs are also clear, though if there’s a weakness here, it’s that we don’t get to see which muscles are being worked in the same as we do when there’s an illustration with a different-colored part to show that.

Bottom line: if you’re looking for an introductory course for kettlebell training that’ll take you from beginner through to the “I now know what I’m doing and can take it from here, thanks” stage.

Click here to check out Body Sculpting With Kettlebells For Women, and get sculpting!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Pistachios vs Pecans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pistachios to pecans, we picked the pistachios.

Why?

Firstly, the macronutrients: pistachios have twice as much protein and fiber. Pecans have more fat, though in both of these nuts the fats are healthy.

The category of vitamins is an easy win for pistachios, with a lot more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, C, and E. Especially the 8x vitamin A, 7x vitamin B6, 4x vitamin C, and 2x vitamin E, and as the percentages are good too, these aren’t small differences. Pecans, meanwhile, boast only a little more vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid, the one whose name means “it’s everywhere”, because that’s how easy it is to get it).

In terms of minerals, pistachios have more calcium, iron, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while pecans have more manganese and zinc. So, a fair win for pistachios on this one.

Adding up the three different kinds of win for pistachios means that *drumroll* pistachios win overall, and it’s not close.

As ever, do enjoy both though, because diversity is healthy!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Instant Quiz Results, No Email Needed

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

❓ Q&A With 10almonds Subscribers!

Q: I like that the quizzes (I’ve done two so far) give immediate results , with no “give us your email to get your results”. Thanks!

A: You’re welcome! That’s one of the factors that influences what things we include here! Our mission statement is “to make health and productivity crazy simple”, and the unwritten part of that is making sure to save your time and energy wherever we reasonably can!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Top 10 Foods That Promote Lymphatic Drainage and Lymph Flow

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Melissa Gallagher, a naturopath by profession, recommends the following 10 foods that she says promote lymphatic drainage and lymph flow, as well as the below-mentioned additional properties:

Ginger

Ginger is a natural anti-inflammatory, which we wrote about here:

Ginger Does A Lot More Than You Think

Turmeric

Turmeric is another natural anti-inflammatory, which we wrote about here:

Why Curcumin (Turmeric) Is Worth Its Weight In Gold

Garlic

Garlic is—you guessed it—another natural anti-inflammatory which we wrote about here:

The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

Pineapple

Pineapple contains a collection of enzymes collectively called bromelain—which is a unique kind of anti-inflammatory, and which we have written about here:

Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

Citrus

Citrus fruits like oranges, lemons, and grapefruits are rich in vitamin C, which can help support the immune system in general.

Cranberry

Cranberries contain antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, which we wrote about here:

Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

The video also explains how cranberry bioactives inhibit adipogenesis and reduces fat congestion in your lymphatic system.

Dandelion Tea

Dandelion is a natural diuretic and anti-inflammatory herb, which we’ve not written about yet!

Nettle Tea

Nettle is a natural diuretic and anti-inflammatory herb, which we’ve also not written about yet!

Healthy Fats

Healthy fats like avocado, nuts, and olive oil can help reduce inflammation and support the immune system.

Fermented Foods

Fermented foods, such as kimchi and sauerkraut, contain probiotics that can improve gut health, which in turn boosts the immune system. You can read all about it here:

Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

Want the full explanation? Here’s the video:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: