8 Signs Of Iodine Deficiency You Might Not Expect

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Health Coach Kait (BSc Nutrition & Exercise) is a certified health and nutrition coach, and today she’s here to talk about iodine—which is important for many of our body functions, from thyroid hormone production to metabolic regulation to heart rate management, as well as more superficial-but-important-too things like our skin and hair.

Kait’s hitlist

Here’s what she recommends we look out for:

- Swollen neck: even a slightly swollen neck might indicate low iodine levels (this is because that’s where the thyroid glands are)

- Hair loss: iodine is needed for healthy hair growth, so a deficiency can lead to hair loss / thinning hair

- Dry and flaky skin: with iodine’s role in our homeostatic system not being covered, our skin can dry out as a result

- Feeling cold all the time: because of iodine’s temperature-regulating activities

- Slow heart rate: A metabolic slump due to iodine deficiency can slow down the heart rate, leading to fatigue and weakness (and worse, if it persists)

- Brain fog: trouble focusing can be a symptom of the same metabolic slump

- Fatigue: this is again more or less the same thing, but she said eight signs, so we’re giving you the eight!

- Irregular period (if you normally have such, of course): because iodine affects reproductive hormones too, an imbalance can disrupt menstrual cycles.

For more on each of these, as well as how to get more iodine in your diet, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Further reading

You might also like to read:

- A Fresh Take On Hypothyroidism

- Foods For Managing Hypothyroidism (incl. Hashimoto’s)

- Eat To Beat Hyperthyroidism!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Aging with Grace – by Dr. David Snowdon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this book is not: a book about Christianity. Don’t worry, we didn’t suddenly change the theme of 10almonds.

Rather, what this book is: a book about a famous large (n=678) study into the biology of aging, that took a population sample of women who had many factors already controlled-for, e.g. they ate the same food, had the same schedule, did the same activities, etc—for many years on end. In other words, a convent of nuns.

This allowed for a lot more to be learned about other factors that influence aging, such as:

- Heredity / genetics in general

- Speaking more than one language

- Supplementing with vitamins or not

- Key adverse events (e.g. stroke)

- Key chronic conditions (e.g. depression)

The book does also cover (as one might expect) the role that community and faith can play in healthy longevity, but since the subjects were 678 communally-dwelling people of faith (thus: no control group of faithless loners), this aspect is discussed only in anecdote, or in reference to other studies.

The author of this book, by the way, was the lead researcher of the study, and he is a well-recognised expert in the field of Alzheimer’s in particular (and Alzheimer’s does feature quite a bit throughout).

The writing style is largely narrative, and/but with a lot of clinical detail and specific data; this is by no means a wishy-washy book.

Bottom line: if you’d like to know what nuns were doing in the 1980s to disproportionally live into three-figure ages, then this book will answer those questions.

Click here to check out Aging with Grace, and indeed age with grace!

Share This Post

-

You can’t reverse the ageing process but these 5 things can help you live longer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

At this time of year many of us resolve to prioritise our health. So it is no surprise there’s a roaring trade of products purporting to guarantee you live longer, be healthier and look more youthful.

While an estimated 25% of longevity is determined by our genes, the rest is determined by what we do, day to day.

There are no quick fixes or short cuts to living longer and healthier lives, but the science is clear on the key principles. Here are five things you can do to extend your lifespan and improve your health.

1. Eat a predominantly plant-based diet

What you eat has a huge impact on your health. The evidence overwhelmingly shows eating a diet high in plant-based foods is associated with health and longevity.

If you eat more plant-based foods and less meat, processed foods, sugar and salt, you reduce your risk of a range of illnesses that shorten our lives, including heart disease and cancer.

Plant-based foods are rich in nutrients, phytochemicals, antioxidants and fibre. They’re also anti-inflammatory. All of this protects against damage to our cells as we age, which helps prevent disease.

No particular diet is right for everyone but one of the most studied and healthiest is the Mediterranean diet. It’s based on the eating patterns of people who live in countries around the Mediterranean Sea and emphases vegetables, fruits, wholegrains, legumes, nuts and seeds, fish and seafood, and olive oil.

2. Aim for a healthy weight

Another important way you can be healthier is to try and achieve a healthy weight, as obesity increases the risk of a number of health problems that shorten our lives.

Obesity puts strain on all of our body systems and has a whole myriad of physiological effects including causing inflammation and hormonal disturbances. These increase your chances of a number of diseases, including heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes and a number of cancers.

In addition to affecting us physically, obesity is also associated with poorer psychological health. It’s linked to depression, low self-esteem and stress.

One of the biggest challenges we face in the developed world is that we live in an environment that promotes obesity. The ubiquitous marketing and the easy availability of high-calorie foods our bodies are hard-wired to crave mean it’s easy to consume too many calories.

3. Exercise regularly

We all know that exercise is good for us – the most common resolution we make this time of year is to do more exercise and to get fitter. Regular exercise protects against chronic illness, lowers your stress and improves your mental health.

While one of the ways exercising helps you is by supporting you to control your weight and lowering your body fat levels, the effects are broader and include improving your glucose (blood sugar) use, lowering your blood pressure, reducing inflammation and improving blood flow and heart function.

While it’s easy to get caught up in all of the hype about different exercise strategies, the evidence suggests that any way you can include physical activity in your day has health benefits. You don’t have to run marathons or go to the gym for hours every day. Build movement into your day in any way that you can and do things that you enjoy.

4. Don’t smoke

If you want to be healthier and live longer then don’t smoke or vape.

Smoking cigarettes affects almost every organ in the body and is associated with both a shorter and lower quality of life. There is no safe level of smoking – every cigarette increases your chances of developing a range of cancers, heart disease and diabetes.

Even if you have been smoking for years, by giving up smoking at any age you can experience health benefits almost immediately, and you can reverse many of the harmful effects of smoking.

If you’re thinking of switching to vapes as a healthy long term option, think again. The long term health effects of vaping are not fully understood and they come with their own health risks.

5. Prioritise social connection

When we talk about living healthier and longer, we tend to focus on what we do to our physical bodies. But one of the most important discoveries over the past decade has been the recognition of the importance of spiritual and psychological health.

People who are lonely and socially isolated have a much higher risk of dying early and are more likely to suffer from heart disease, stroke, dementia as well as anxiety and depression.

Although we don’t fully understand the mechanisms, it’s likely due to both behavioural and biological factors. While people who are more socially connected are more likely to engage in healthy behaviours, there also seems to be a more direct physiological effect of loneliness on the body.

So if you want to be healthier and live longer, build and maintain your connections to others.

Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, Epidemiology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Seriously Useful Communication Skills!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Are Communication Skills, Really?

Superficially, communication is “conveying an idea to someone else”. But then again…

Superficially, painting is “covering some kind of surface in paint”, and yet, for some reason, the ceiling you painted at home is not regarded as equally “good painting skills” as Michaelangelo’s, with regard to the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

All kinds of “Dark Psychology” enthusiasts on YouTube, authors of “Office Machiavelli” handbooks, etc, tell us that good communication skills are really a matter of persuasive speaking (or writing). And let’s not even get started on “pick-up artist” guides. Bleugh.

Not to get too philosophical, but here at 10almonds, we think that having good communication skills means being able to communicate ideas simply and clearly, and in a way that will benefit as many people as possible.

The implications of this for education are obvious, but what of other situations?

Conflict Resolution

Whether at work or at home or amongst friends or out in public, conflict will happen at some point. Even the most well-intentioned and conscientious partners, family, friends, colleagues, will eventually tread on our toes—or we, on theirs. Often because of misunderstandings, so much precious time will be lost needlessly. It’s good for neither schedule nor soul.

So, how to fix those situations?

I’m OK; You’re OK

In the category of “bestselling books that should have been an article at most”, a top-tier candidate is Thomas Harris’s “I’m OK; You’re OK”.

The (very good) premise of this (rather padded) book is that when seeking to resolve a conflict or potential conflict, we should look for a win-win:

- I’m not OK; you’re not OK ❌

- For example: “Yes, I screwed up and did this bad thing, but you too do bad things all the time”

- I’m OK; you’re not OK ❌

- For example: “It is not I who screwed up; this is actually all your fault”

- I’m not OK; you’re OK ❌

- For example: “I screwed up and am utterly beyond redemption; you should immediately divorce/disown/dismiss/defenestrate me”

- I’m OK; you’re OK ✅

- For example: “I did do this thing which turned out to be incorrect; in my defence it was because you said xyz, but I can understand why you said that, because…” and generally finding a win-win outcome.

So far, so simple.

“I”-Messages

In a conflict, it’s easy to get caught up in “you did this, you did that”, often rushing to assumptions about intent or meaning. And, the closer we are to the person in question, the more emotionally charged, and the more likely we are to do this as a knee-jerk response.

“How could you treat me this way?!” if we are talking to our spouse in a heated moment, perhaps, or “How can you treat a customer this way?!” if it’s a worker at Home Depot.

But the reality is that almost certainly neither our spouse nor the worker wanted to upset us.

Going on the attack will merely put them on the defensive, and they may even launch their own counterattack. It’s not good for anyone.

Instead, what really happened? Express it starting with the word “I”, rather than immediately putting it on the other person. Often our emotions require a little interrogation before they’ll tell us the truth, but it may be something like:

“I expected x, so when you did/said y instead, I was confused and hurt/frustrated/angry/etc”

Bonus: if your partner also understands this kind of communication situation, so much the better! Dark psychology be damned, everything is best when everyone knows the playbook and everyone is seeking the best outcome for all sides.

The Most Powerful “I”-Message Of All

Statements that start with “I” will, unless you are rules-lawyering in bad faith, tend to be less aggressive and thus prompt less defensiveness. An important tool for the toolbox, is:

“I need…”

Softly spoken, firmly if necessary, but gentle. If you do not express your needs, how can you expect anyone to fulfil them? Be that person a partner or a retail worker or anyone else. Probably they want to end the conflict too, so throw them a life-ring and they will (if they can, and are at least halfway sensible) grab it.

- “I need an apology”

- “I need a moment to cool down”

- “I need a refund”

- “I need some reassurance about…” (and detail)

Help the other person to help you!

Everything’s best when it’s you (plural) vs the problem, rather than you (plural) vs each other.

Apology Checklist

Does anyone else remember being forced to write an insincere letter of apology as a child, and the literary disaster that probably followed? As adults, we (hopefully) apologize when and if we mean it, and we want our apology to convey that.

What follows will seem very formal, but honestly, we recommend it in personal life as much as professional. It’s a ten-step apology, and you will forget these steps, so we recommend to copy and paste them into a Notes app or something, because this is of immeasurable value.

It’s good not just for when you want to apologize, but also, for when it’s you who needs an apology and needs to feel it’s sincere. Give your partner (if applicable) a copy of the checklist too!

- Statement of apology—say “I’m sorry”

- Name the offense—say what you did wrong

- Take responsibility for the offense—understand your part in the problem

- Attempt to explain the offense (not to excuse it)—how did it happen and why

- Convey emotions; show remorse

- Address the emotions/damage to the other person—show that you understand or even ask them how it affected them

- Admit fault—understand that you got it wrong and like other human beings you make mistakes

- Promise to be better—let them realize you’re trying to change

- Tell them how you will try to do it different next time and finally

- Request acceptance of the apology

Note: just because you request acceptance of the apology doesn’t mean they must give it. Maybe they won’t, or maybe they need time first. If they’re playing from this same playbook, they might say “I need some time to process this first” or such.

Want to really superpower your relationship? Read this together with your partner:

Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love, and, as a bonus:

The Hold Me Tight Workbook: A Couple’s Guide for a Lifetime of Love

Share This Post

- I’m not OK; you’re not OK ❌

Related Posts

-

Welcoming the Unwelcome – by Pema Chödrön

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There’s a lot in life that we don’t get to choose. Some things we have zero control over, like the weather. Others, we can only influence, like our health. Still yet others might give us an illusion of control, only to snatch it away, like a financial reversal or a bereavement.

How, then, to suffer those “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” and come through the other side with an even mind and a whole heart?

Author Pema Chödrön has a guidebook for us.

Quick note: this book does not require the reader to have any particular religious faith to enjoy its benefits, but the author is a nun. As such, the way she describes things is generally within the frame of her religion. So that’s a thing to be aware of in case it might bother you. That said…

The largest part of her approach is one that psychology might describe as rational emotive behavioral therapy.

As such, we are encouraged to indeed “meet with triumph and disaster, and treat those two imposters just the same”, and more importantly, she lays out the tools for us to do so.

Does this mean not caring? No! Quite the opposite. It is expected, and even encouraged, that we might care very much. But: this book looks at how to care and remain compassionate, to others and to ourselves.

For Chödrön, welcoming the unwelcome is about de-toothing hardship by accepting it as a part of the complex tapestry of life, rather than something to be endured.

Bottom line: this book can greatly increase the reader’s ability to “go placidly amid the noise and haste” and bring peace to an often hectic world—starting with our own.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

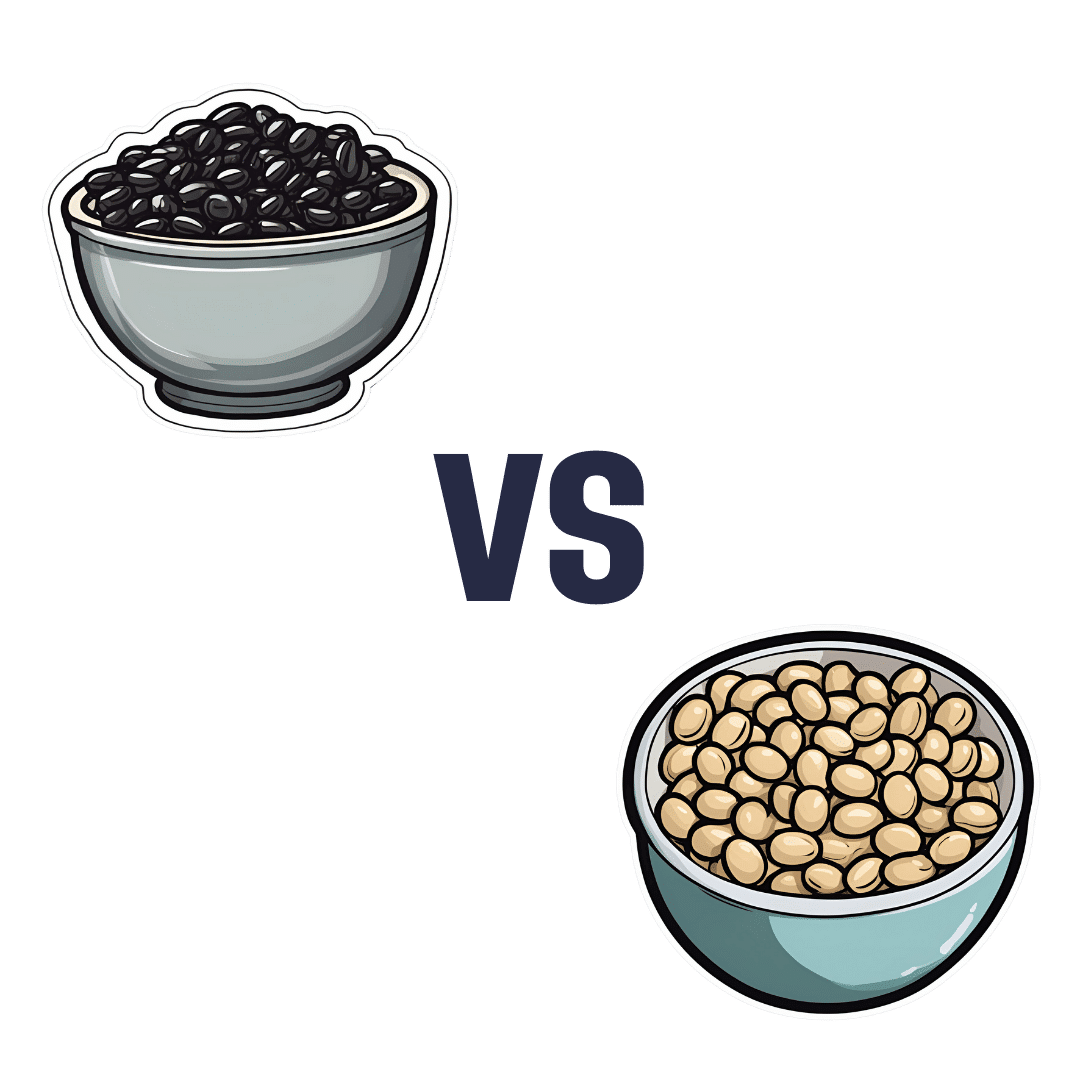

Black Beans vs Soy Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing black beans to soy beans, we picked the soy.

Why?

Quite some heavyweights competing here today, as both have been the winners of other comparisons!

Comparing these two’s macros first, black beans have 3x the carbs and slightly more fiber, while soy has more than 2x the protein. We’ll call this a win for soy.

As a tangential note, it’s worth remembering also that soy is a complete protein (contains a full set of the amino acids we need), whereas black beans… Well, technically they are too, but in practicality, they only have much smaller amounts of some amino acids.

In terms of vitamins, black beans have more of vitamins B1, B3, B5, B9, and E, while soy beans have more of vitamins A, B2, B6, C, K, and choline. A marginal win for soy here.

In the category of minerals, however, it isn’t close: black beans are not higher in any minerals, while soy beans are higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. An overwhelming win for soy.

It should be noted, however, that black beans are still very good for minerals! They just look bad when standing next to soy, that’s all.

So, enjoy either or both, but for nutritional density, soy wins the day.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Plant vs Animal Protein: Head to Head

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Xylitol vs Erythritol – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing xylitol to erythritol, we picked the xylitol.

Why?

They’re both sugar alcohols, which so far as the body is concerned are neither sugars nor alcohols in the way those words are commonly understood; it’s just a chemical term. The sugars aren’t processed as such by the body and are passed as dietary fiber, and nor is there any intoxicating effect as one might expect from an alcohol.

In terms of macronutrients, while technically they both have carbs, for all functional purposes they don’t and just have a little fiber.

In terms of micronutrients, they don’t have any.

The one thing that sets them apart is their respective safety profiles. Xylitol is prothrombotic and associated with major adverse cardiac events (CI=95, adjusted hazard ratio=1.57, range=1.12-2.21), while erythritol is also prothrombotic and more strongly associated with major adverse cardiac events (CI=95, adjusted hazard ratio=2.21, range=1.20-4.07).

So, xylitol is bad and erythritol is worse, which means the relatively “healthier” is xylitol. We don’t recommend either, though.

Studies for both:

- Xylitol is prothrombotic and associated with cardiovascular risk

- The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk

Links for the specific products we compared, in case our assessment hasn’t put you off them:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- The WHO’s New View On Sugar-Free Sweeteners ← the WHO’s advice is “don’t”

- Stevia vs Acesulfame Potassium – Which is Healthier? ← stevia’s pretty much the healthiest artificial sweetener around, though, if you’re going to use one

- The Fascinating Truth About Aspartame, Cancer, & Neurotoxicity ← under the cold light of science, aspartame isn’t actually as bad as it was painted a few decades ago, mostly by a viral hoax letter. Per the WHO’s advice, it’s still good to avoid sweeteners in general, however.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: