52 Weeks to Better Mental Health – by Dr. Tina Tessina

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written before about the health benefits of journaling, but how to get started, and how to make it a habit, and what even to write about?

Dr. Tessina presents a year’s worth of journaling prompts with explanations and exercises, and no, they’re not your standard CBT flowchart things, either. Rather, they not only prompt genuine introspection, but also are crafted to be consistently uplifting—yes, even if you are usually the most disinclined to such positivity, and approach such exercises with cynicism.

There’s an element of guidance beyond that, too, and as such, this book is as much a therapist-in-a-book as you might find. Of course, no book can ever replace a competent and compatible therapist, but then, competent and compatible therapists are often harder to find and can’t usually be ordered for a few dollars with next-day shipping.

Bottom line: if undertaken with seriousness, this book will be an excellent investment in your mental health and general wellbeing.

Click here to check out 52 Weeks to Better Mental Health, and get on the best path for you!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Accidental falls in the older adult population: What academic research shows

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Accidental falls are among the leading causes of injury and death among adults 65 years and older worldwide. As the aging population grows, researchers expect to see an increase in the number of fall injuries and related health spending.

Falls aren’t unique to older adults. Nealy 684,000 people die from falls each year globally. Another 37.3 million people each year require medical attention after a fall, according to the World Health Organization. But adults 65 and older account for the greatest number of falls.

In the United States, more than 1 in 4 older adults fall each year, according to the National Institute on Aging. One in 10 report a fall injury. And the risk of falling increases with age.

In 2022, health care spending for nonfatal falls among older adults was $80 billion, according to a 2024 study published in the journal Injury Prevention.

Meanwhile, the fall death rate in this population increased by 41% between 2012 and 2021, according to the latest CDC data.

“Unfortunately, fall-related deaths are increasing and we’re not sure why that is,” says Dr. Jennifer L. Vincenzo, an associate professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in the department of physical therapy and the Center for Implementation Research. “So, we’re trying to work more on prevention.”

Vincenzo advises journalists to write about how accidental falls can be prevented. Remind your audiences that accidental falls are not an inevitable consequence of aging, and that while we do decline in many areas with age, there are things we can do to minimize the risk of falls, she says. And expand your coverage beyond the national Falls Prevention Awareness Week, which is always during the first week of fall — Sept. 23 to 27 this year.

Below, we explore falls among older people from different angles, including injury costs, prevention strategies and various disparities. We have paired each angle with data and research studies to inform your reporting.

Falls in older adults

In 2020, 14 million older adults in the U.S. reported falling during the previous year. In 2021, more than 38,700 older adults died due to unintentional falls, according to the CDC.

A fall could be immediately fatal for an older adult, but many times it’s the complications from a fall that lead to death.

The majority of hip fractures in older adults are caused by falls, Vincenzo says, and “it could be that people aren’t able to recover [from the injury], losing function, maybe getting pneumonia because they’re not moving around, or getting pressure injuries,” she says.

In addition, “sometimes people restrict their movement and activities after a fall, which they think is protective, but leads to further functional declines and increases in fall risk,” she adds.

Factors that can cause a fall include:

- Poor eyesight, reflexes and hearing. “If you cannot hear as well, anytime you’re doing something in your environment and there’s a noise, it will be really hard for you to focus on hearing what that noise is and what it means and also moving at the same time,” Vincenzo says.

- Loss of strength, balance, and mobility with age, which can lessen one’s ability to prevent a fall when slipping or tripping.

- Fear of falling, which usually indicates decreased balance.

- Conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, or problems with nerves or feet that can affect balance.

- Conditions like incontinence that cause rushed movement to the bathroom.

- Cognitive impairment or certain types of dementia.

- Unsafe footwear such as backless shoes or high heels.

- Medications or medication interactions that can cause dizziness or confusion.

- Safety hazards in the home or outdoors, such as poor lighting, steps and slippery surfaces.

Related Research

Nonfatal and Fatal Falls Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, 2020–2021

Ramakrishna Kakara, Gwen Bergen, Elizabeth Burns and Mark Stevens. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, September 2023.Summary: Researchers analyzed data from the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System — a landline and mobile phone survey conducted each year in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia — and data from the 2021 National Vital Statistics System to identify patterns of injury and death due to falls in the U.S. by sex and state for adults 65 years and older. Among the findings:

- The percentage of women who reported falling was 28.9%, compared with 26.1% of men.

- Death rates from falls were higher among white and American Indian or Alaska Native older adults than among older adults from other racial and ethnic groups.

- In 2020, the percentage of older adults who reported falling during the past year ranged from 19.9% in Illinois to 38.0% in Alaska. The national estimate for 18 states was 27.6%.

- In 2021, the unintentional fall-related death rate among older adults ranged from 30.7 per 100,000 older adults in Alabama to 176.5 in Wisconsin. The national estimate for 26 states was 78.

“Although common, falls among older adults are preventable,” the authors write. “Health care providers can talk with patients about their fall risk and how falls can be prevented.”

Trends in Nonfatal Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years — United States, 2012-2018

Briana Moreland, Ramakrishna Kakara and Ankita Henry. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, July 2020.Summary: Researchers compared data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Among the findings:

- The percentage of older adults reporting a fall increased from 2012 to 2016, then slightly decreased from 2016 to 2018.

- Even with this decrease in 2018, older adults reported 35.6 million falls. Among those falls, 8.4 million resulted in an injury that limited regular activities for at least one day or resulted in a medical visit.

“Despite no significant changes in the rate of fall-related injuries from 2012 to 2018, the number of fall-related injuries and health care costs can be expected to increase as the proportion of older adults in the United States grows,” the authors write.

Understanding Modifiable and Unmodifiable Older Adult Fall Risk Factors to Create Effective Prevention Strategies

Gwen Bergen, et al. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, October 2019.Summary: Researchers used data from the 2016 U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to better understand the association between falls and fall injuries in older adults and factors such as health, state and demographic characteristics. Among the findings:

- Depression had the strongest association with falls and fall injuries. About 40% of older adults who reported depression also reported at least one fall; 15% reported at least one fall injury.

- Falls and depression have several factors in common, including cognitive impairment, slow walking speed, poor balance, slow reaction time, weakness, low energy and low levels of activity.

- Other factors associated with an increased risk of falling include diabetes, vision problems and arthritis.

“The multiple characteristics associated with falls suggest that a comprehensive approach to reducing fall risk, which includes screening and assessing older adult patients to determine their unique, modifiable risk factors and then prescribing tailored care plans that include evidence-based interventions, is needed,” the authors write.

Health care use and cost

In addition to being the leading cause of injury, falls are the leading cause of hospitalization in older adults. Each year, about 3 million older adults visit the emergency department due to falls. More than 1 million get hospitalized.

In 2021, falls led to more than 38,000 deaths in adults 65 and older, according to the CDC.

The annual financial medical toll of falls among adults 65 years and older is expected to be more than $101 billion by 2030, according to the National Council on Aging, an organization advocating for older Americans.

Related research

Healthcare Spending for Non-Fatal Falls Among Older Adults, USA

Yara K. Haddad, et al. Injury Prevention, July 2024.Summary: In 2015, health care spending related to falls among older adults was roughly $50 billion. This study aims to update the estimate, using the 2017, 2019 and 2021 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, the most comprehensive and complete survey available on the Medicare population. Among the findings:

- In 2020, health care spending for non-fatal falls among older adults was $80 billion.

- Medicare paid $53.3 billion of the $80 billion, followed by $23.2 billion paid by private insurance or patients and $3.5 billion by Medicaid.

“The burden of falls on healthcare systems and healthcare spending will continue to rise if the risk of falls among the aging population is not properly addressed,” the authors write. “Many older adult falls can be prevented by addressing modifiable fall risk factors, including health and functional characteristics.”

Cost of Emergency Department and Inpatient Visits for Fall Injuries in Older Adults Lisa Reider, et al. Injury, February 2024.

Summary: The researchers analyzed data from the 2016-2018 National Inpatient Sample and National Emergency Department Sample, which are large, publicly available patient databases in the U.S. that include all insurance payers such as Medicare and private insurance. Among the findings:

- During 2016-2018, more than 920,000 older adults were admitted to the hospital and 2.3 million visited the emergency department due to falls. The combined annual cost was $19.2 billion.

- More than half of hospital admissions were due to bone fractures. About 14% of these admissions were due to multiple fractures and cost $2.5 billion.

“The $20 billion in annual acute treatment costs attributed to fall injury indicate an urgent need to implement evidence-based fall prevention interventions and underscores the importance of newly launched [emergency department]-based fall prevention efforts and investments in geriatric emergency departments,” the authors write.

Hip Fracture-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths by Mechanism of Injury Among Adults Aged 65 and Older, United States 2019

Briana L. Moreland, Jaswinder K. Legha, Karen E. Thomas and Elizabeth R. Burns. Journal of Aging and Health, June 2024.Summary: The researchers calculated hip fracture-related U.S. emergency department visits, hospitalizations and deaths among older adults, using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and the National Vital Statistics System. Among the findings:

- In 2019, there were 318,797 emergency department visits, 290,130 hospitalizations and 7,731 deaths related to hip fractures among older adults.

- Nearly 88% of emergency department visits and hospitalizations and 83% of deaths related to hip fractures were caused by falls.

- These rates were highest among those living in rural areas and among adults 85 and older. More specifically, among adults 85 and older, the rate of hip fracture-related emergency department visits was nine times higher than among adults between 65 and 74 years old.

“Falls are common among older adults, but many are preventable,” the authors write. “Primary care providers can prevent falls among their older patients by screening for fall risk annually or after a fall, assessing modifiable risk factors such as strength and balance issues, and offering evidence-based interventions to reduce older adults’ risk of falls.”

Fall prevention

Several factors, including exercising, managing medication, checking vision and making homes safer can help prevent falls among older adults.

“Exercise is one of the best interventions we know of to prevent falls,” Vincenzo says. But “walking in and of itself will not help people to prevent falls and may even increase their risk of falling if they are at high risk of falls.”

The National Council on Aging also has a list of evidence-based fall prevention programs, including activities and exercises that are shown to be effective.

The National Institute on Aging has a room-by-room guide on preventing falls at home. Some examples include installing grab bars near toilets and on the inside and outside of the tub and shower, sitting down while preparing food to prevent fatigue, and keeping electrical cords near walls and away from walking paths.

There are also national and international initiatives to help prevent falls.

Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injuries, or STEADI, is an initiative by the CDC’s Injury Center to help health care providers who treat older adults. It helps providers screen patients for fall risk, assess their fall risk factors and reduce their risk by using strategies that research has shown to be effective. STEADI’s guidelines are in line with the American and British Geriatric Societies’ Clinical Practice Guidelines for fall prevention.

“We’re making some iterations right now to STEADI that will come out in the next couple of years based on the World Falls Guidelines, as well as based on clinical providers’ feedback on how to make [STEADI] more feasible,” Vincenzo says.

The World Falls Guidelines is an international initiative to prevent falls in older adults. The guidelines are the result of the work of 14 international experts who came together in 2019 to consider whether new guidelines on fall prevention were needed. The task force then brought together 96 experts from 39 countries across five continents to create the guidelines.

The CDC’s STEADI initiative has a screening questionnaire for consumers to check their risk of falls, as does the National Council on Aging.

On the policy side, U.S. Rep. Carol Miller, R-W.V., and Melanie Stansbury, D-N.M., introduced the Stopping Addiction and Falls for the Elderly (SAFE) Act in March 2024. The bill would allow occupational and physical therapists to assess fall risks in older adults as part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Benefit. The bill was sent to the House Subcommittee on Health in the same month.

Meanwhile, older adults’ attitudes toward falls and fall prevention are also pivotal. For many, coming to terms with being at risk of falls and making changes such as using a cane, installing railings at home or changing medications isn’t easy for all older adults, studies show.

“Fall is a four-letter F-word in a way to older adults,” says Vincenzo, who started her career as a physical therapist. “It makes them feel ‘old.’ So, it’s a challenge on multiple fronts: U.S. health care infrastructure, clinical and community resources and facilitating health behavior change.”

Related research

Environmental Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community

Lindy Clemson, et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, March 2023.Summary: This review includes 22 studies from 10 countries involving a total of 8,463 older adults who live in the community, which includes their own home, a retirement facility or an assisted living facility, but not a hospital or nursing home. Among the findings:

- Removing fall hazards at home reduced the number of falls by 38% among older adults at a high risk of having a fall, including those who have had a fall in the past year, have been hospitalized or need support with daily activities. Examples of fall hazards at home include a stairway without railings, a slippery pathway or poor lighting.

- It’s unclear whether checking prescriptions for eyeglasses, wearing special footwear or installing bed alarm systems reduces the rate of falls.

- It’s also not clear whether educating older adults about fall risks reduces their fall risk.

The Influence of Older Adults’ Beliefs and Attitudes on Adopting Fall Prevention Behaviors

Judy A. Stevens, David A. Sleet and Laurence Z. Rubenstein. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. January 2017.Summary: Persuading older adults to adopt interventions that reduce their fall risk is challenging. Their attitudes and beliefs about falls play a large role in how well they accept and adopt fall prevention strategies, the authors write. Among the common attitudes and beliefs:

- Many older adults believe that falls “just happen,” are a normal result of aging or are simply due to bad luck.

- Many don’t acknowledge or recognize their fall risk.

- For many, falls are considered to be relevant only for frail or very old people.

- Many believe that their home environment or daily activities can be a risk for fall, but do not consider biological factors such as dizziness or muscle weakness.

- For many, fall prevention simply consists of “being careful” or holding on to things when moving about the house.

“To reduce falls, health care practitioners have to help patients understand and acknowledge their fall risk while emphasizing the positive benefits of fall prevention,” the authors write. “They should offer patients individualized fall prevention interventions as well as provide ongoing support to help patients adopt and maintain fall prevention strategies and behaviors to reduce their fall risk. Implementing prevention programs such as CDC’s STEADI can help providers discuss the importance of falls and fall prevention with their older patients.”

Reframing Fall Prevention and Risk Management as a Chronic Condition Through the Lens of the Expanded Chronic Care Model: Will Integrating Clinical Care and Public Health Improve Outcomes?

Jennifer L. Vincenzo, Gwen Bergen, Colleen M. Casey and Elizabeth Eckstrom. The Gerontologist, June 2024.Summary: The authors recommend approaching fall prevention from the lens of chronic disease management programs because falls and fall risk are chronic issues for many older adults.

“Policymakers, health systems, and community partners can consider aligning fall risk management with the [Expanded Chronic Care Model], as has been done for diabetes,” the authors write. “This can help translate high-quality research on the effectiveness of fall prevention interventions into daily practice for older adults to alter the trajectory of older adult falls and fall-related injuries.”

Disparities

Older adults face several barriers to reducing their fall risk. Accessing health care services and paying for services such as physical therapy is not feasible for everyone. Some may lack transportation resources to go to and from medical appointments. Social isolation can increase the risk of death from falls. In addition, physicians may not have the time to fit in a fall risk screening while treating older patients for other health concerns.

Moreover, implementing fall risk screening, assessment and intervention in the current U.S. health care structure remains a challenge, Vincenzo says.

Related research

Mortality Due to Falls by County, Age Group, Race, and Ethnicity in the USA, 2000-19: A Systematic Analysis of Health Disparities

Parkes Kendrick, et al. The Lancet Public Health, August 2024.Summary: Researchers analyzed death registration data from the U.S. National Vital Statistics System and population data from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics to estimate annual fall-related mortality. The data spanned from 2000 to 2019 and includes all age groups. Among the findings:

- The disparities between racial and ethnic populations varied widely by age group. Deaths from falls among younger adults were highest for the American Indian/Alaska Native population, while among older adults it was highest for the white population.

- For older adults, deaths from falls were particularly high in the white population within clusters of counties across states including Florida, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

- One factor that could contribute to higher death rates among white older adults is social isolation, the authors write. “Studies suggest that older Black and Latino adults are more likely to have close social support compared with older white adults, while AIAN and Asian individuals might be more likely to live in multigenerational households,” they write.

“Among older adults, current prevention techniques might need to be restructured to reduce frailty by implementing early prevention and emphasizing particularly successful interventions. Improving social isolation and evaluating the effectiveness of prevention programs among minoritized populations are also key,” the authors write.

Demographic Comparisons of Self-Reported Fall Risk Factors Among Older Adults Attending Outpatient Rehabilitation

Mariana Wingood, et al. Clinical Interventions in Aging, February 2024.Summary: Researchers analyzed the electronic health record data of 108,751 older adults attending outpatient rehabilitation within a large U.S. health care system across seven states, between 2018 and 2022. Among the findings:

- More than 44% of the older adults were at risk of falls; nearly 35% had a history of falls.

- The most common risk factors for falls were diminished strength, gait and balance.

- Compared to white older adults, Native American/Alaska Natives had the highest prevalence of fall history (43.8%) and Hispanics had the highest prevalence of falls with injury (56.1%).

“Findings indicate that rehabilitation providers should perform screenings for these impairments, including incontinence and medication among females, loss of feeling in the feet among males, and all Stay Independent Questionnaire-related fall risk factors among Native American/Alaska Natives, Hispanics, and Blacks,” the authors write.

Resources and articles

- National Institute on Aging

- National Council on Aging

- Gerontological Society of America

- Home Health Agencies Failed To Report Over Half of Falls With Major Injury and Hospitalization Among Their Medicare Patients, a 2023 report from the U.S Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General.

- 6 tips for improving new coverage of older people, a tip sheet from The Journalist’s Resource.

- Crosswalk and pedestrian safety: What you need to know from recent research, from The Journalist’s Resource.

- Aging-in-place technology challenges and trends, a resource from the Association of Health Care Journalists.

- Successful aging at home: what reporters should know, a resource from the Association of Health Care Journalists.

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

-

The Mind-Gut Connection – by Dr. Emeran Mayer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed books about the mind-gut connection before, so what makes this one stand out?

Firstly, it’s a lot more comprehensive than the usual “please, we’re begging you, eat some fiber”.

And yes, of course that’s part of it. Prebiotics, probiotics, reduce fried and processed foods, reduce sugar/alcohol, reduce meat, and again, eat some greenery.

But where this book really comes into its own is looking more thoroughly at the gut microbiota and their function. Dr. Mayer goes well beyond “there are good and bad bacteria” and looks at the relationship each of them have with the body’s many hormones, and especially neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine.

He also looks at the two-way connection between brain and gut. Yes, our gut gives us “gut feelings”, but 10% of communication between the brain and gut is in the other direction; he explores what that means for us, too.

Finally, he does give a lot of practical advice, not just dietary but also behavioral, to make the most of our mind-gut connection and make it work for our health, rather than against it.

Bottom line: this is the best book on the brain-gut connection that this reviewer has read so far, and certainly the most useful if you already know about gut-healthy nutrition, and are looking to take your understanding to the next level.

Click here to check out The Mind-Gut Connection, and start making yours work for your benefit!

Share This Post

-

Sunflower Seeds vs Pumpkin Seeds – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing sunflower seeds to pumpkin seeds, we picked the pumpkin seeds.

Why?

Both seeds have a good spread of vitamins and minerals, but pumpkin seeds have more. Sunflower seeds come out on top for copper and manganese, but everything else that’s present in either of them (in the category of vitamins and minerals, anyway), pumpkin seeds have more.

There is one other thing that sunflower seeds have more of than pumpkin seeds, and that’s fat. The fat is mostly of healthy varieties, so it’s not a negative factor, but it does mean that if you’re eating a calorie-controlled diet, you’ll get more bang for your buck (i.e. better micronutrient-to-calorie ratio) if you pick pumpkin seeds.

If you’re not concerned about fat/calories, and/or you actively want to consume more of those, then sunflower seeds are still a fine choice.

When it comes down to it, a diverse diet is best, so enjoying both might be the best option of all.

Want to get some?

We don’t sell them, but here for your convenience are example products on Amazon:

Sunflower Seeds | Pumpkin Seeds

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Why it’s a bad idea to mix alcohol with some medications

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Anyone who has drunk alcohol will be familiar with how easily it can lower your social inhibitions and let you do things you wouldn’t normally do.

But you may not be aware that mixing certain medicines with alcohol can increase the effects and put you at risk.

When you mix alcohol with medicines, whether prescription or over-the-counter, the medicines can increase the effects of the alcohol or the alcohol can increase the side-effects of the drug. Sometimes it can also result in all new side-effects.

How alcohol and medicines interact

The chemicals in your brain maintain a delicate balance between excitation and inhibition. Too much excitation can lead to convulsions. Too much inhibition and you will experience effects like sedation and depression.

Alcohol works by increasing the amount of inhibition in the brain. You might recognise this as a sense of relaxation and a lowering of social inhibitions when you’ve had a couple of alcoholic drinks.

With even more alcohol, you will notice you can’t coordinate your muscles as well, you might slur your speech, become dizzy, forget things that have happened, and even fall asleep.

Alcohol can affect the way a medicine works.

Jonathan Kemper/UnsplashMedications can interact with alcohol to produce different or increased effects. Alcohol can interfere with the way a medicine works in the body, or it can interfere with the way a medicine is absorbed from the stomach. If your medicine has similar side-effects as being drunk, those effects can be compounded.

Not all the side-effects need to be alcohol-like. Mixing alcohol with the ADHD medicine ritalin, for example, can increase the drug’s effect on the heart, increasing your heart rate and the risk of a heart attack.

Combining alcohol with ibuprofen can lead to a higher risk of stomach upsets and stomach bleeds.

Alcohol can increase the break-down of certain medicines, such as opioids, cannabis, seizures, and even ritalin. This can make the medicine less effective. Alcohol can also alter the pathway of how a medicine is broken down, potentially creating toxic chemicals that can cause serious liver complications. This is a particular problem with paracetamol.

At its worst, the consequences of mixing alcohol and medicines can be fatal. Combining a medicine that acts on the brain with alcohol may make driving a car or operating heavy machinery difficult and lead to a serious accident.

Who is at most risk?

The effects of mixing alcohol and medicine are not the same for everyone. Those most at risk of an interaction are older people, women and people with a smaller body size.

Older people do not break down medicines as quickly as younger people, and are often on more than one medication.

Older people also are more sensitive to the effects of medications acting on the brain and will experience more side-effects, such as dizziness and falls.

Smaller and older people are often more affected.

Alfonso Scarpa/UnsplashWomen and people with smaller body size tend to have a higher blood alcohol concentration when they consume the same amount of alcohol as someone larger. This is because there is less water in their bodies that can mix with the alcohol.

What drugs can’t you mix with alcohol?

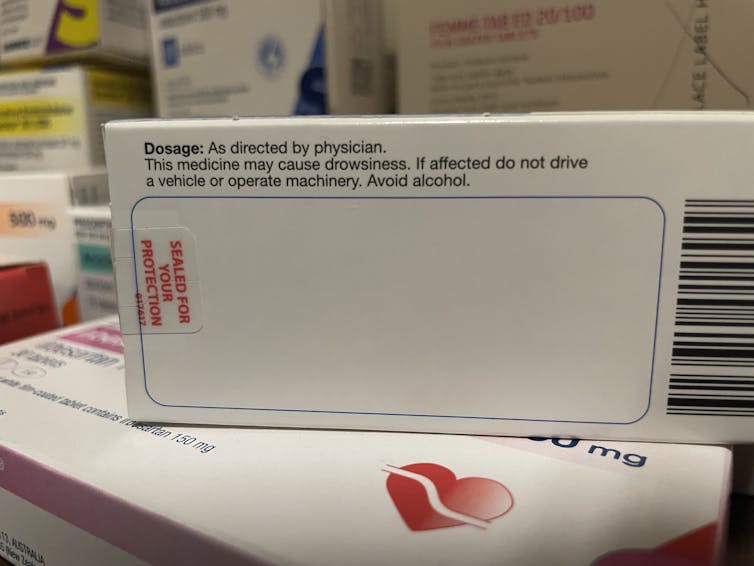

You’ll know if you can’t take alcohol because there will be a prominent warning on the box. Your pharmacist should also counsel you on your medicine when you pick up your script.

The most common alcohol-interacting prescription medicines are benzodiazepines (for anxiety, insomnia, or seizures), opioids for pain, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and some antibiotics, like metronidazole and tinidazole.

Medicines will carry a warning if you shouldn’t take them with alcohol.

Nial WheateIt’s not just prescription medicines that shouldn’t be mixed with alcohol. Some over-the-counter medicines that you shouldn’t combine with alcohol include medicines for sleeping, travel sickness, cold and flu, allergy, and pain.

Next time you pick up a medicine from your pharmacist or buy one from the local supermarket, check the packaging and ask for advice about whether you can consume alcohol while taking it.

If you do want to drink alcohol while being on medication, discuss it with your doctor or pharmacist first.

Nial Wheate, Associate Professor of the School of Pharmacy, University of Sydney; Jasmine Lee, Pharmacist and PhD Candidate, University of Sydney; Kellie Charles, Associate Professor in Pharmacology, University of Sydney, and Tina Hinton, Associate Professor of Pharmacology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Generation M – by Dr. Jessica Shepherd

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Menopause is something that very few people are adequately prepared for despite its predictability, and also something that very many people then neglect to take seriously enough.

Dr. Shepherd encourages a more proactive approach throughout all stages of menopause and beyond; she discusses “the preseason, the main event, and the after-party” (perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause), which is important, because typically people take up an interest in perimenopause, are treating it like a marathon by menopause, and when it comes to postmenopause, it’s easy to think “well, that’s behind me now”, and it’s not, because untreated menopause will continue to have (mostly deleterious) cumulative effects until death.

As for HRT, there’s a chapter on that of course, going into quite some detail. There is also plenty of attention given to popular concerns such as managing weight changes and libido changes, as well as oft-neglected topics such as brain changes, as well as things considered more cosmetic but that can have a big impact on mental health, such as skin and hair.

The style throughout is pop-science; friendly without skimping on detail and including plenty of good science.

Bottom line: if you’d like a fairly comprehensive overview of the changes that occur from perimenopause all the way to menopause and well beyond, then this is a great book for that.

Click here to check out Generation M, and live well at every stage of life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Tilapia vs Cod – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing tilapia to cod, we picked the tilapia.

Why?

Another case of “that which is more expensive is not necessarily the healthier”!

In terms of macros, tilapia has more protein and fats, as well as more omega-3 (and omega-6). On the downside, tilapia does have relatively more saturated fat, but at 0.94g/100g, it’s not exactly butter.

The vitamins category sees that tilapia has more of vitamins B1, B3, B5, B12, D, and K, while cod has more of vitamins B6, B9, and choline. A moderate win for tilapia.

When it comes to minerals, things are most divided; tilapia has more copper, iron, phosphorus, potassium, manganese, and selenium, while cod has more magnesium and zinc. An easy win for tilapia.

One other thing to note is that both of these fish contain mercury these days (and it’s worth noting: cod has nearly 10x more mercury). Mercury is, of course, not exactly a health food.

So, excessive consumption of either is not recommended, but out of the two, tilapia is definitely the one to pick.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Farmed Fish vs Wild Caught: Know The Health Differences

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: