How Regularity Of Sleep Can Be Even More Important Than Duration

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A recent, large (n=72,269) 8-year prospective* observational study of adults aged 40-79 has found an association between irregular sleep and major cardiovascular events.

*this means they started the study at a given point, and measured what happened for the next eight years—as opposed to a retrospective study, which would look at what had happened during the previous 8 years.

As to what qualifies as major cardiovascular events, they counted:

- Heart attack

- Cardiac arrest

- Stroke

- Cardiovascular death (any)

Irregular sleep, meanwhile, was defined per a bell curve of participants. Based on a sleep regularity index (SRI) score, those with a score of 87 or more were on the “regular” side of the curve, and those with a score of 72 or lower were on the “irregular” side of the curve.

What they found is that irregular sleep is associated with major cardiovascular events, regardless of the actual amount of sleep that people got. So in other words, you could be sleeping 9 hours per day, but if it’s a different 9 hours each day, your cardiovascular risk will still be higher.

How much higher?

- For those in the middle of the curve (so, moderate irregularity), it was 8% higher than those on the “regular” side.

- For those on the “irregular” side of the curve, it was 26% higher than those on the “regular” side.

All of the above is after taking into account confounding variables such as age, physical activity levels, discretionary screen time, fruit, vegetable, and coffee intake, alcohol consumption, smoking, mental health issues, medication use, and shift work. Which is quite something, given that shift work is a very common reason for irregular sleep schedules in a lot of people.

Limitations

While, as noted above, they did their best to account for a lot of things, this was an observational study, not an interventional study or a randomized controlled trial, and as such, it cannot truly establish cause and effect.

For example, an observational study in the 90s found that the sport most strongly associated with longevity was polo. For any unfamiliar, it’s a game played on horseback with mallets and balls. Why was this game so much better than, say, swimming? And the answer is most likely that polo is played almost entirely by very rich people. It wasn’t the sport that enhanced longevity—it was the wealth.

So similarly here, it could be for example that people who are predisposed to heart conditions, are prone to having irregular schedules. We won’t know for sure until we have interventional studies (and we probably can’t get RCTs for this, for practical reasons).

Still, it seems likely that the association is indeed causal, in which case, having a regular sleep schedule if at all possible seems like a very good way to look after one’s health.

You can read more about the study here:

Irregular sleep may elevate risk of major cardiovascular events

Practical take-away

This study strongly suggests that sleep regularity is even more important than sleep duration.

This means that there is extra reason to not sleep in past one’s normal getting-up time, even if one had a less restful night.

That’s the end of sleep that’s the most important in practical terms, too, because we can control our getting-up time, whereas we can’t really control our going-to-sleep time, because it’s perfectly possible to just lie there awake.

So, controlling the getting-up time is really the key to the whole thing. See also:

Calculate (And Enjoy) The Perfect Night’s Sleep

And for scope, you might enjoy reading:

Morning Larks vs Night Owls: How Much Can We Control Our Sleep Schedule?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Metabolic Health Roadmap – by Brenda Wollenberg

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The term “roadmap” is often used in informative books, but in this case, Wollenberg (a nutritionist with decades of experience) really does deliver what can very reasonably be described as a roadmap:

She provides chapters in the form of legs of a journey [to better metabolic health], and those legs are broadly divided into an “information center” to deliver new information, a “rest stop” for reflection, “roadwork” to guide the reader through implementing the information we just learned, in a practical fashion, and finally “traveller assistance” to give additional support / resources, as well as any potential troubleshooting, etc.

The information and guidance within are all based on very good science; a lot is what you will have read already about blood sugar management (generally the lynchpin of metabolic health in general), but there’s also a lot about leveraging epigenetics for our benefit, rather than being sabotaged by such.

There’s a little guidance that falls outside of nutrition (sleep, exercise, etc), but for the most part, Wollenberg stays within her own field of expertise, nutrition.

The style is idiosyncratic; it’s very clear that her goal is providing the promised roadmap, and not living up to any editor’s wish or publisher’s hope of living up to industry standard norms of book formatting. However, this pays off, because her delivery is clear and helpful while remaining personable and yet still bringing just as much actual science, and this makes for a very pleasant and informative read.

Bottom line: if you’d like to improve your metabolic health, as well as get held-by-the-hand through your health-improvement journey by a charming guide, this is very much the book for you!

Click here to check out the Metabolic Health Roadmap, and start taking steps!

Share This Post

-

The Epigenetics Revolution – by Dr. Nessa Carey

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you enjoyed the book “Inheritance” that we reviewed a couple of days ago, you might love this as a “next read” book. But you can also just dive straight in here, if you like!

This one, as the title suggests, focuses entirely on epigenetics—how our life events can shape our genetic expression, and that of our descendants. Or to look at it in the other direction, how our genetic expression can be shaped by the life experiences of, for example, our grandparents.

The style of this book is very much pop-science, but contains a lot of information from hard science throughout. We learn not just about longitudinal population studies as one might expect, but also about the intricacies of DNA methylation and histone modifications, for example.

Depending on your outlook, you may find some of this very bleak (“great, I am shackled by what my grandparents did”) or very optimism-inducing (“oh wow, I’m not nearly so constrained by genetics as I thought; this stuff is so malleable!”). This is also the same author who wrote “Hacking The Code of Life“, by the way, but we’ll review that another day.

Bottom line: this book is the best one-shot primer on epigenetics that this reviewer has read (you may be wondering how many that is, and the answer is… about seven or so? I’m not good at counting).

Click here to check out The Epigenetics Revolution, and learn how dynamic you really are!

Share This Post

-

Ear Candling: Is It Safe & Does It Work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Does This Practice Really Hold A Candle To Evidence-Based Medicine?

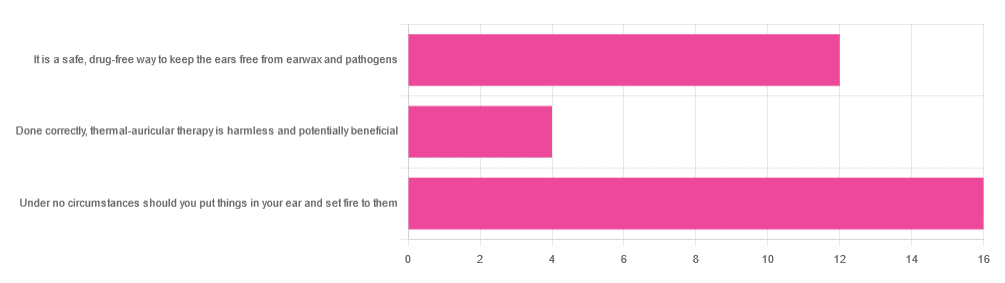

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion of ear candling, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of responses:

- Exactly 50% said “Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them”

- About 38% said “It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens”

- About 13% said “Done correctly, thermal-auricular therapy is harmless and potentially beneficial”

This means that if we add the two positive-to-candling answers together, it’s a perfect 50:50 split between “do it” and “don’t do it”.

(Yes, 38%+13%=51%, but that’s because we round to the nearest integer in these reports, and more precisely it was 37.5% and 12.5%)

So, with the vote split, what does the science say?

First, a quick bit of background: nobody seems keen to admit to having invented this. One of the major manufacturers of ear candles refers to them as “Hopi” candles, which the actual Hopi tribe has spent a long time asking them not to do, as it is not and never has been used by the Hopi people. Other proposed origins offered by advocates of ear candling include Traditional Chinese Medicine (not used), Ancient Egypt (no evidence of such whatsoever), and Atlantis:

Quackwatch | Why Ear Candling Is Not A Good Idea

It is a safe, drug-free way to keep the ears free from earwax and pathogens: True or False?

False! In a lot of cases of alternative therapy claims, there’s an absence of evidence that doesn’t necessarily disprove the treatment. In this case, however, it’s not even an open matter; its claims have been actively disproven by experimentation:

- It doesn’t remove earwax; on the contrary, experimentation “showed no removal of cerumen from the external auditory canal. Candle wax was actually deposited in some“

- It doesn’t remove pathogens, and the proposed mechanism of action for removing pathogens, that of the “chimney effect”: the idea that the burning candle creates a vacuum that draws wax out of the ear along with debris and bacteria, simply does not work; on the contrary, “Tympanometric measurements in an ear canal model demonstrated that ear candles do not produce negative pressure”.

- It isn’t safe; on the contrary, “Ear candles have no benefit in the management of cerumen and may result in serious injury”

In a medium-sized survey (n=122), the following injuries were reported:

- 13 x burns

- 7 x occlusion of the ear canal

- 6 x temporary hearing loss

- 3 x otitis externa (this also called “swimmer’s ear”, and is an inflammation of the ear, accompanied by pain and swelling)

- 1 x tympanic membrane perforation

Indeed, authors of one paper concluded:

❝Ear candling appears to be popular and is heavily advertised with claims that could seem scientific to lay people. However, its claimed mechanism of action has not been verified, no positive clinical effect has been reliably recorded, and it is associated with considerable risk.

No evidence suggests that ear candling is an effective treatment for any condition. On this basis, we believe it can do more harm than good and we recommend that GPs discourage its use❞

Source: Canadian Family Physician | Ear Candling

Under no circumstances should you put things in your ear and set fire to them: True or False?

True! It’s generally considered good advice to not put objects in general in your ears.

Inserting flaming objects is a definite no-no. Please leave that for the Cirque du Soleil.

You may be thinking, “but I have done this and suffered no ill effects”, which seems reasonable, but is an example of survivorship bias in action—it doesn’t make the thing in question any safer, it just means you were one of the one of the ones who got away unscathed.

If you’re wondering what to do instead… Ear oils can help with the removal of earwax (if you don’t want to go get it sucked out at a clinic—the industry standard is to use a suction device, which actually does what ear candles claim to do). For information on safely getting rid of earwax, see our previous article:

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Apples vs Oranges – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apples to oranges, we picked the oranges.

Why?

In terms of macros, the two fruits are approximately equal (and indeed, on average, precisely equal in the most important metric, which is fiber). So, a tie here.

In the category of vitamins, apples are higher in vitamin K, while oranges are higher in vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, C, and choline. An easy win for oranges this time.

When it comes to minerals, apples have more iron and manganese, while oranges have more calcium, copper, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Another easy win for oranges.

So, adding up the sections, a clear win for oranges. But, by all means, enjoy either or both! Diversity is good.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Cherries’ Very Healthy Wealth Of Benefits!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cherries’ Health Benefits Simply Pop

First, be aware, there are different kinds:

Sweet & Sour

Cherries can be divided into sweet vs sour. These are mostly nutritionally similar, though sour ones do have some extra benefits.

Sweet and sour cherries are closely related but botanically different plants; it’s not simply a matter of ripeness (or preparation).

These can mostly be sorted into varieties of Prunus avium and Prunus cerasus, respectively:

Cherry Antioxidants: From Farm to Table

Sour cherry varieties include morello and montmorency, so look out for those names in particular when doing your grocery-shopping.

You may remember that it’s a good rule of thumb that foods that are more “bitter, astringent, or pungent” will tend to have a higher polyphenol content (that’s good):

Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

Juiced up

Almost certainly for reasons of budget and convenience, as much as for standardization, most studies into the benefits of cherries have been conducted using concentrated cherry juice as a supplement.

At home, we need not worry so much about standardization, and our budget and convenience are ours to manage. To this end, as a general rule of thumb, whole fruits are pretty much always better than juice:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Antioxidant & anti-inflammatory!

Cherries are a very good source of antioxidants, and as such they also reduce inflammation, which in turn means ameliorating autoimmune diseases, from common things like arthritis…

…to less common things like gout:

Cherry Consumption and the Risk of Recurrent Gout Attacks

This can also be measured by monitoring uric acid metabolites:

Consumption of cherries lowers plasma urate in healthy women

Anti-diabetic effect

Most of the studies on this have been rat studies, and the human studies have been less “the effect of cherry consumption on diabetes” and more a matter of separate studies adding up to this conclusion in, the manner of “cherries have this substance, this substance has this effect, therefore cherries will have this effect”. You can see an example of this discussed over the course of 15 studies, here:

A Review of the Health Benefits of Cherries ← skip to section 2.2.1: “Cherry Intake And Diabetes”

In short, the jury is out on cherry juice, but eating cherries themselves (much like getting plenty of fruit in general) is considered good against diabetes.

Good for healthy sleep

For this one, the juice suffices (actual cherries are still recommended, but the juice gave clear significant positive results):

Pilot Study of the Tart Cherry Juice for the Treatment of Insomnia and Investigation of Mechanisms ← this was specifically in people over the age of 50

Importantly, it’s not that cherries have a sedative effect, but rather they support the body’s ability to produce melatonin adequately when the time comes:

Effect of tart cherry juice (Prunus cerasus) on melatonin levels and enhanced sleep quality

Post-exercise recovery

Cherries are well-known for boosting post-exercise recovery, though they may actually improve performance during exercise too, if eaten beforehand/

For example, these marathon-runners who averaged 13% compared to placebo control:

As for its recovery benefits, we wrote about this before:

How To Speed Up Recovery After A Workout (According To Actual Science)

Want to get some?

We recommend your local supermarket (or farmer’s market!), but if for any reason you prefer to take a supplement, here’s an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Resveratrol & Healthy Aging

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Resveratrol & Healthy Aging

Resveratrol is the compound found in red grapes, and thus in red wine, that have resulted in red wine being sometimes touted as a heart-healthy drink.

However, at the levels contained in red wine, you’d need to drink 100–1000 glasses of wine per day (depending on the wine) to get the dose of resveratrol that was associated with heart health benefits in mouse studies.

Which also means: if you are not a mouse, you might need to drink even more than that!

Further reading: can we drink to good health?

Resveratrol supplementation

Happily, resveratrol supplements exist. But what does resveratrol do?

It lowers blood pressure:

Effect of resveratrol on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

It improves blood lipid levels:

It improves insulin sensitivity:

It has neuroprotective effects too:

Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptides

Is it safe?

For most people, it is generally recognized as safe. However, if you are on blood-thinners or otherwise have a bleeding disorder, you might want to skip it:

Antiplatelet activity of synthetic and natural resveratrol in red wine

You also might want to check with your pharmacist/doctor, if you’re on blood pressure meds, anxiety meds, or immunosuppressants, as it can increase the amount of these drugs that will then stay in your system:

Resveratrol modulates drug- and carcinogen-metabolizing enzymes in a healthy volunteer study

And as ever, of course, if unsure just check with your pharmacist/doctor, to be on the safe side.

Where to get it?

We don’t sell it, but here’s an example product on Amazon for your convenience

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: