What’s the difference between a psychopath and a sociopath? Less than you might think

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Articles about badly behaved people and how to spot them are common. You don’t have to Google or scroll too much to find headlines such as 7 signs your boss is a psychopath or How to avoid the sociopath next door.

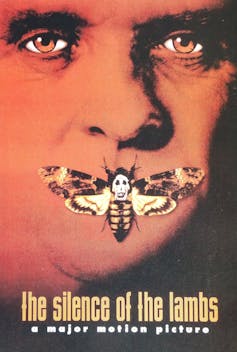

You’ll often see the terms psychopath and sociopath used somewhat interchangeably. That applies to perhaps the most famous badly behaved fictional character of all – Hannibal Lecter, the cannibal serial killer from The Silence of the Lambs.

In the book on which the movie is based, Lecter is described as a “pure sociopath”. But in the movie, he’s described as a “pure psychopath”. Psychiatrists have diagnosed him with something else entirely.

So what’s the difference between a psychopath and a sociopath? As we’ll see, these terms have been used at different times in history, and relate to some overlapping concepts.

What’s a psychopath?

Psychopathy has been mentioned in the psychiatric literature since the 1800s. But the latest edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known colloquially as the DSM) doesn’t list it as a recognised clinical disorder.

Since the 1950s, labels have changed and terms such as “sociopathic personality disturbance” have been replaced with antisocial personality disorder, which is what we have today.

Someone with antisocial personality disorder has a persistent disregard for the rights of others. This includes breaking the law, repeated lying, impulsive behaviour, getting into fights, disregarding safety, irresponsible behaviours, and indifference to the consequences of their actions.

To add to the confusion, the section in the DSM on antisocial personality disorder mentions psychopathy (and sociopathy) traits. In other words, according to the DSM the traits are part of antisocial personality disorder but are not mental disorders themselves.

US psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley provided the first formal description of psychopathy traits in his 1941 book The Mask of Sanity. He based his description on his clinical observations of nine male patients in a psychiatric hospital. He identified several key characteristics, including superficial charm, unreliability and a lack of remorse or shame.

Canadian psychologist Professor Robert Hare refined these characteristics by emphasising interpersonal, emotional and lifestyle characteristics, in addition to the antisocial behaviours listed in the DSM.

When we draw together all these strands of evidence, we can say a psychopath manipulates others, shows superficial charm, is grandiose and is persistently deceptive. Emotional traits include a lack of emotion and empathy, indifference to the suffering of others, and not accepting responsibility for how their behaviour impacts others.

Finally, a psychopath is easily bored, sponges off others, lacks goals, and is persistently irresponsible in their actions.

So how about a sociopath?

The term sociopath first appeared in the 1930s, and was attributed to US psychologist George Partridge. He emphasised the societal consequences of behaviour that habitually violates the rights of others.

Academics and clinicians often used the terms sociopath and psychopath interchangeably. But some preferred the term sociopath because they said the public sometimes confused the word psychopath with psychosis.

“Sociopathic personality disturbance” was the term used in the first edition of the DSM in 1952. This aligned with the prevailing views at the time that antisocial behaviours were largely the product of the social environment, and that behaviours were only judged as deviant if they broke social, legal, and/or cultural rules.

Some of these early descriptions of sociopathy are more aligned with what we now call antisocial personality disorder. Others relate to emotional characteristics similar to Cleckley’s 1941 definition of a psychopath.

In short, different people had different ideas about sociopathy and, even today, sociopathy is less-well defined than psychopathy. So there is no single definition of sociopathy we can give you, even today. But in general, its antisocial behaviours can be similar to ones we see with psychopathy.

Over the decades, the term sociopathy fell out of favour. From the late 60s, psychiatrists used the term antisocial personality disorder instead.

Born or made?

Both “sociopathy” (what we now call antisocial personality disorder) and psychopathy have been associated with a wide range of developmental, biological and psychological causes.

For example, people with psychopathic traits have certain brain differences especially in regions associated with emotions, inhibition of behaviour and problem solving. They also appear to have differences associated with their nervous system, including a reduced heart rate.

However, sociopathy and its antisocial behaviours are a product of someone’s social environment, and tends to run in families. These behaviours has been associated with physical abuse and parental conflict.

What are the consequences?

Despite their fictional portrayals – such as Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs or Villanelle in the TV series Killing Eve – not all people with psychopathy or sociopathy traits are serial killers or are physically violent.

But psychopathy predicts a wide range of harmful behaviours. In the criminal justice system, psychopathy is strongly linked with re-offending, particularly of a violent nature.

In the general population, psychopathy is associated with drug dependence, homelessness, and other personality disorders. Some research even showed psychopathy predicted failure to follow COVID restrictions.

But sociopathy is less established as a key risk factor in identifying people at heightened risk of harm to others. And sociopathy is not a reliable indicator of future antisocial behaviour.

In a nutshell

Neither psychopathy nor sociopathy are classed as mental disorders in formal psychiatric diagnostic manuals. They are both personality traits that relate to antisocial behaviours and are associated with certain interpersonal, emotional and lifestyle characteristics.

Psychopathy is thought to have genetic, biological and psychological bases that places someone at greater risk of violating other people’s rights. But sociopathy is less clearly defined and its antisocial behaviours are the product of someone’s social environment.

Of the two, psychopathy has the greatest use in identifying someone who is most likely to cause damage to others.

Bruce Watt, Associate Professor in Psychology, Bond University and Katarina Fritzon, Associate Professor of Psychology, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Is “Extra Virgin” Worth It?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝I was wondering, is the health difference important between extra virgin olive oil and regular?❞

Assuming that by “regular” you mean “virgin and still sold as a food product”, then there are health differences, but they’re not huge. Or at least: not nearly so big as the differences between those and other oils.

Virgin olive oil (sometimes simply sold as “olive oil”, with no claims of virginity) has been extracted by the same means as extra virgin olive oil, that is to say: purely mechanical.

The difference is that extra virgin olive oil comes from the first pressing*, so the free fatty acid content is slightly lower (later checked and validated and having to score under a 0.8% limit for “extra virgin” instead of 2% limit for a mere “virgin”).

*Fun fact: in Arabic, extra virgin is called “البكر الممتاز“, literally “the amazing first-born”, because of this feature!

It’s also slightly higher in mono-unsaturated fatty acids, which is a commensurately slight health improvement.

It’s very slightly lower in saturated fats, which is an especially slight health improvement, as the saturated fats in olive oil are amongst the healthiest saturated fats one can consume.

On which fats are which:

The truth about fats: the good, the bad, and the in-between

And our own previous discussion of saturated fats in particular:

Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy?

Probably the strongest extra health-benefit of extra virgin is that while that first pressing squeezes out oil with the lowest free fatty acid content, it squeezes out oil with the highest polyphenol content, along with other phytonutrients:

If you enjoy olive oil, then springing for extra virgin is worth it if that’s not financially onerous, both for health reasons and taste.

However, if mere “virgin” is what’s available, it’s no big deal to have that instead; it still has a very similar nutritional profile, and most of the same benefits.

Don’t settle for less than “virgin”, though.

While some virgin olive oils aren’t marked as such, if it says “refined” or “blended”, then skip it. These will have been extracted by chemical means and/or blended with completely different oils (e.g. canola, which has a very different nutritional profile), and sometimes with a dash of virgin or extra virgin, for the taste and/or so that they can claim in big writing on the label something like:

a blend of

EXTRA VIRGIN OLIVE OIL

and other oils…despite having only a tiny amount of extra virgin olive oil in it.

Different places have different regulations about what labels can claim.

The main countries that produce olives (and the EU, which contains and/or directly trades with those) have this set of rules:

International Olive Council: Designations and definitions of Olive Oils

…which must be abided by or marketers face heavy fines and sanctions.

In the US, the USDA has its own set of rules based on the above:

USDA | Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil Grades and Standards

…which are voluntary (not protected by law), and marketers can pay to have their goods certified if they want.

So if you’re in the US, look for the USDA certification or it really could be:

- What the USDA calls “US virgin olive oil not fit for human consumption”, which in the IOC is called “lamp oil”*

- crude pomace-oil (oil made from the last bit of olive paste and then chemically treated)

- canola oil with a dash of olive oil

- anything yellow and oily, really

*This technically is virgin olive oil insofar as it was mechanically extracted, but with defects that prevent it from being sold as such, such as having a free fatty acid content above the cut-off, or just a bad taste/smell, or some sort of contamination.

See also: Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols

(the above paper has a handy infographic if you scroll down just a little)

Where can I get some?

Your local supermarket, probably, but if you’d like to get some online, here’s an example product on Amazon for your convenience

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Chetna’s Healthy Indian – by Chetna Makan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Indian food is wonderful—a subjective opinion perhaps, but a popular view, and one this reviewer certainly shares. And of course, cooking with plenty of vegetables and spices is a great way to get a lot of health benefits.

There are usually downsides though, such as that in a lot of Indian cookbooks, every second thing is deep-fried, and what’s not deep-fried contains an entire day or more’s saturated fat content in ghee, and a lot of sides have more than their fair share of sugar.

This book fixes all that, by offering 80 recipes that prioritize health without sacrificing flavor.

The recipes are, as the title suggests, vegetarian, though many are not vegan (yogurt and cheese featuring in many recipes). That said, even if you are vegan, it’s pretty easy to veganize those with the obvious plant-based substitutions. If you have soy yogurt and can whip up vegan paneer yourself (here’s our own recipe for that), you’re pretty much sorted.

The cookbook strikes a good balance of being neither complicated nor “did we really need a recipe for this?” basic, and delivers value in all of its recipes. The ingredients, often a worry for many Westerners, should be easily found if you have a well-stocked supermarket near you; there’s nothing obscure here.

Bottom line: if you’d like to cook more Indian food and want your food to be exciting without also making your blood pressure exciting, then this is an excellent book for keeping you well-nourished, body and soul.

Click here to check out Chetna’s Healthy Indian, and spice up your culinary repertoire!

Share This Post

-

10 Healthiest Foods You Should Eat In The Morning

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For many of us, our creative minds aren’t their absolute best first thing in the morning, and it’s easy to reach for what’s available, if we haven’t planned ahead.

So here’s some inspiration for the coming week! If you’re a regular coffee-and-toast person, at least consider alternating some of these with that:

- Oatmeal with fresh fruit: fiber, energy, protein, vitamins and minerals (10almonds tip: we recommend making it as overnight oats! Same nutrients, lower glycemic index)

- Greek yogurt parfait: probiotic gut benefits, along with all the goodness of fruit

- Avocado toast: so many nutrients; most famous for the healthy fats, but there’s lots more in there too!

- Egg + vegetable scramble: protein, healthy fats, vitamins and minerals, fiber

- Smoothie bowl: many nutrients—But be aware that blending will reduce fiber and make the sugar quicker to enter your bloodstream. Still not bad as an occasional feature for the sake of variety, though!

- Wholegrain pancakes: energy, fiber, and whatever your toppings! Fresh fruit is a top-tier choice; the video suggests maple syrup; we however invite you to try aged balsamic vinegar instead (sounds unlikely, we know, but try it and you’ll see; it is so delicious and your blood sugars will thank you too!)

- Chia pudding: so many nutrients in this one; chia seeds are incredible!

- Quinoa breakfast bowl: the healthy grains are a great start to the day, and contain a fair bit of protein too, and served with nuts, seeds, and diced fruit, many more nutrients get added to the mix. Unclear why the video-makers want to put honey or maple syrup on everything.

- Berries: lots of vitamins, fiber, hydration, and very many polyphenols

For a quick visual overview, and a quick-start preparation guide for the ones that aren’t just “berries” or similar, enjoy this short (3:11) video:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

PS: They said 10, and we only counted 9. Where is the tenth one? Who would say “10 things” and then ostensibly only have 9? Who would do such a thing?!

About that chia pudding…

It’s a great way to get a healthy dose of protein, healthy fats, antioxidants, and a lot of other benefits for the heart and brain:

The Tiniest Seeds With The Most Value

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Who you are and where you live shouldn’t determine your ability to survive cancer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In Canada, nearly everyone has a cancer story to share. It affects one in every two people, and despite improvements in cancer survivorship, one out of every four people affected by cancer still will die from it.

As a scientist dedicated to cancer care, I work directly with patients to reimagine a system that was never designed for them in the first place – a system in which your quality of care depends on social drivers like your appearance, your bank statements and your postal code.

We know that poverty, poor nutrition, housing instability and limited access to education and employment can contribute to both the development and progression of cancer. Quality nutrition and regular exercise reduce cancer risk but are contingent on affordable food options and the ability to stay active in safe, walkable neighbourhoods. Environmental hazards like air pollution and toxic waste elevate the risk of specific cancers, but are contingent on the built environment, laws safeguarding workers and the availability of affordable housing.

On a health-system level, we face implicit biases among care providers, a lack of health workforce competence in addressing the social determinants of health, and services that do not cater to the needs of marginalized individuals.

Indigenous peoples, racialized communities, those with low income and gender diverse individuals face the most discrimination in health care, resulting in inadequate experiences, missed diagnosis and avoidance of care. One patient living in subsidized housing told me, “You get treated like a piece of garbage – you come out and feel twice as bad.”

As Canadians, we benefit from a taxpayer funded health-care system that encompasses cancer care services. The average Canadian enjoys a life expectancy of more than 80 years and Canada boasts high cancer survival rates. While we have made incredible strides in cancer care, we must work together to ensure these benefits are equally shared amongst all people in Canada. We need to redesign systems of care so that they are:

- Anti-oppressive. We must begin by understanding and responding to historical and systemic racism that shapes cancer risk, access to care and quality of life for individuals facing marginalizing conditions. Without tackling the root causes, we will never be able to fully close the cancer care gap. This commitment involves undoing intergenerational trauma and harm through public policies that elevate the living and working conditions of all people.

- Patient-centric. We need to prioritize patient needs, preferences and values in all aspects of their health-care experience. This means tailoring treatments and services to individual patient needs. In policymaking, it involves creating policies that are informed by and responsive to the real-life experiences of patients. In research, it involves engaging patients in the research process and ensuring studies are relevant to and respectful of their unique perspectives and needs. This holistic approach ensures that patients’ perspectives are central to all aspects of health care.

- Socially just. We must strive for a society in which everyone has equal access to resources, opportunities and rights, and systemic inequalities and injustices are actively challenged and addressed. When redesigning the cancer care system, this involves proactive practices that create opportunities for all people, particularly those experiencing the most marginalization, to become involved in systemic health-care decision-making. A system that is responsive to the needs of the most marginalized will ultimately work better for all people.

Who you are, how you look, where you live and how much money you make should never be the difference between life and death. Let us commit to a future in which all people have the resources and support to prevent and treat cancer so that no one is left behind.

This article is republished from HealthyDebate under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Quit Drinking – by Rebecca Dolton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many “quit drinking” books focus on tips you’ve heard already—cut down like this, rearrange your habits like that, make yourself accountable like so, add a reward element this way, etc.

Dolton takes a different approach.

She focuses instead on the underlying processes of addiction, so as to not merely understand them to fight them, but also to use them against the addiction itself.

This is not just a social or behavioral analysis, by the way, and goes into some detail into the physiological factors of the addiction—including such things as the little-talked about relationship between addiction and gut flora. Candida albans, found in most if not all humans to some extent, gets really out of control when given certain kinds of sugars (including those from alcohol); it grows, eventually puts roots through the intestinal walls (ouch!) and the more it grows, the more it demands the sugars it craves, so the more you feed it.

Quite a motivator to not listen to such cravings! It’s not even you that wants it, it’s the Candida!

Anyway, that’s just one example; there are many. The point here is that this is a well-researched, well-written book that sets itself apart from many of its genre.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Pine Nuts vs Pecans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pine nuts to pecans, we picked the pine nuts.

Why?

Both have their merits!

In terms of macros, pine nuts have more protein while pecans have more fiber. They’re about equal on fats, although pine nuts have more polyunsaturated fat and pecans have more monounsaturated fat, of which, both are healthy. They’re also about equal on carbs. So really it comes down to the subjective choice between prioritizing protein and prioritizing fiber. On principle, we pick fiber, which gives the win to pecans, but your preference in this regard may differ; prioritizing the protein would give the win to pine nuts.

In the category of vitamins, pine nuts have more of vitamins B2, B3, B9, E, K, and choline, while pecans have more of vitamins A, B1, B5, B6, and C. Thus, a 6:5 marginal win for pine nuts.

Looking at the minerals, pine nuts have more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc, while pecans have more calcium and selenium. An easy win for pine nuts this time.

Adding up the sections makes for a win for pine nuts, but of course, enjoy either or (preferably) both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: