The Vitamin Solution – by Dr. Romy Block & Dr. Arielle Levitan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A quick note: it would be remiss of us not to mention that the authors of this book are also the founders of a vitamin company, thus presenting a potential conflict of interest.

That said… In this reviewer’s opinion, the book does seem balanced and objective, regardless.

We talk a lot about supplements here at 10almonds, especially in our Monday Research Review editions. And yesterday, we featured a book by a doctor who hates supplements. Today, we feature a book by two doctors who have made them their business.

The authors cover all the most common vitamins and minerals popularly enjoyed as supplements, and examine:

- why people take them

- factors affecting whether they help

- problems that can arise

- complicating factors

The “complicating factors” include, for example, the way many vitamins and/or minerals interplay with each other, either by requiring the presence of another, or else competing for resources for absorption, or needing to be delicately balanced on pain of diverse woes.

This is the greatest value of the book, perhaps; it’s where most people go wrong with supplementation, if they go wrong.

While both authors are medical doctors, Dr. Romy Block is an endocrinologist specifically, and she clearly brought a lot of extra attention to relevant metabolic/thyroid issues, and how vitamins and minerals (such as thiamin and iron) can improve or sabotage such, depending on various factors that she explains. Informative, and so far as this reviewer could see, objective and well-balanced.

Bottom line: supplementation is a vast and complex topic, but this book does a fine job of demystifying and simplifying it in a clear and objective fashion, without resorting to either scaremongering or hype.

Click here to check out The Vitamin Solution, and upgrade your knowledge!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

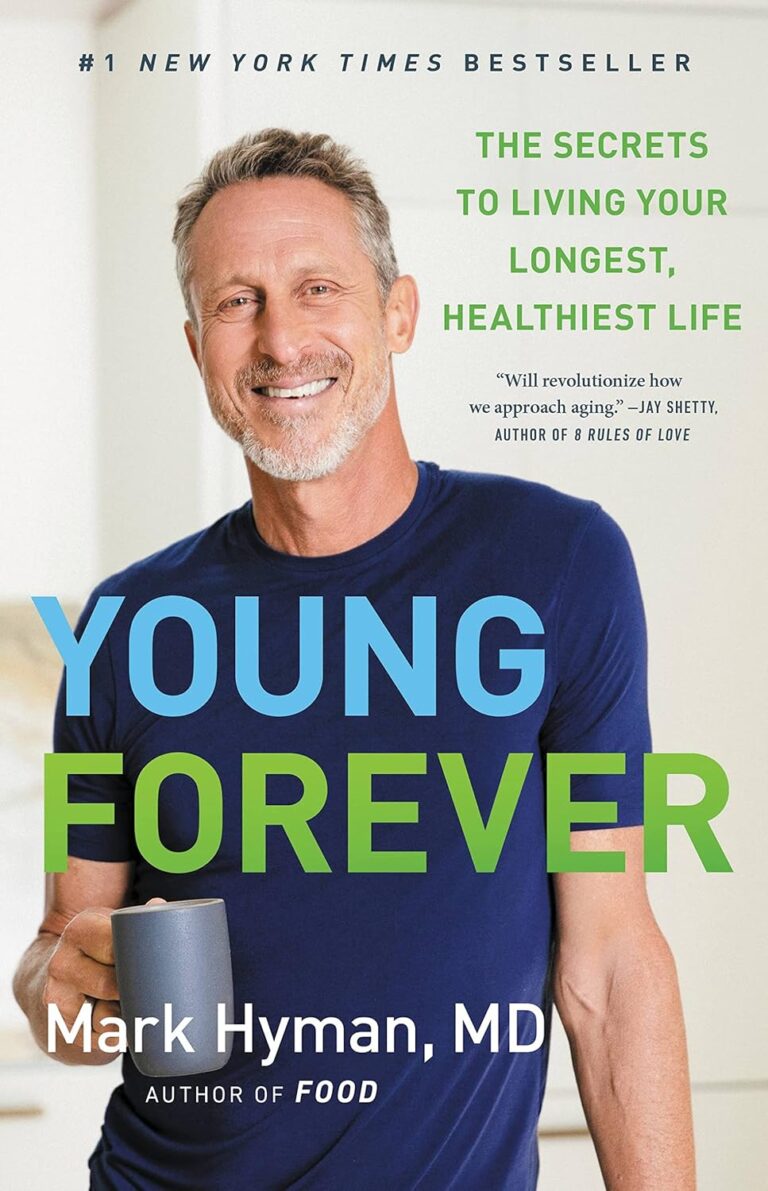

The End of Old Age – by Dr. Marc Agronin

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this book is not: a book about ending aging. For that, you would want to check out “Ending Aging”, by Dr. Aubrey de Grey.

What this book actually is: a book about the purpose of aging. As in: “aging: to what end?”, and then the book answers that question.

Rather than viewing aging as solely a source of decline, this book (while not shying away from that) resolutely examines the benefits of old age—from clinically defining wisdom, to exploring the many neurological trade-offs (e.g., “we lose this thing but we get this other thing in the process”), and the assorted ways in which changes in our brain change our role in society, without relegating us to uselessness—far from it!

The style of the book is deep and meaningful prose throughout. Notwithstanding the author’s academic credentials and professional background in geriatric psychiatry, there’s no hard science here, just comprehensible explanations of psychiatry built into discussions that are often quite philosophical in nature (indeed, the author additionally has a degree in psychology and philosophy, and it shows).

Bottom line: if you’d like your own aging to be something you understand better and can actively work with rather than just having it happen to you, then this is an excellent book for you.

Share This Post

-

To tackle gendered violence, we also need to look at drugs, trauma and mental health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

After several highly publicised alleged murders of women in Australia, the Albanese government this week pledged more than A$925 million over five years to address men’s violence towards women. This includes up to $5,000 to support those escaping violent relationships.

However, to reduce and prevent gender-based and intimate partner violence we also need to address the root causes and contributors. These include alcohol and other drugs, trauma and mental health issues.

Why is this crucial?

The World Health Organization estimates 30% of women globally have experienced intimate partner violence, gender-based violence or both. In Australia, 27% of women have experienced intimate partner violence by a co-habiting partner; almost 40% of Australian children are exposed to domestic violence.

By gender-based violence we mean violence or intentionally harmful behaviour directed at someone due to their gender. But intimate partner violence specifically refers to violence and abuse occurring between current (or former) romantic partners. Domestic violence can extend beyond intimate partners, to include other family members.

These statistics highlight the urgent need to address not just the aftermath of such violence, but also its roots, including the experiences and behaviours of perpetrators.

What’s the link with mental health, trauma and drugs?

The relationships between mental illness, drug use, traumatic experiences and violence are complex.

When we look specifically at the link between mental illness and violence, most people with mental illness will not become violent. But there is evidence people with serious mental illness can be more likely to become violent.

The use of alcohol and other drugs also increases the risk of domestic violence, including intimate partner violence.

About one in three intimate partner violence incidents involve alcohol. These are more likely to result in physical injury and hospitalisation. The risk of perpetrating violence is even higher for people with mental ill health who are also using alcohol or other drugs.

It’s also important to consider traumatic experiences. Most people who experience trauma do not commit violent acts, but there are high rates of trauma among people who become violent.

For example, experiences of childhood trauma (such as witnessing physical abuse) can increase the risk of perpetrating domestic violence as an adult.

Childhood trauma can leave its mark on adults years later. Roman Yanushevsky/Shutterstock Early traumatic experiences can affect the brain and body’s stress response, leading to heightened fear and perception of threat, and difficulty regulating emotions. This can result in aggressive responses when faced with conflict or stress.

This response to stress increases the risk of alcohol and drug problems, developing PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), and increases the risk of perpetrating intimate partner violence.

How can we address these overlapping issues?

We can reduce intimate partner violence by addressing these overlapping issues and tackling the root causes and contributors.

The early intervention and treatment of mental illness, trauma (including PTSD), and alcohol and other drug use, could help reduce violence. So extra investment for these are needed. We also need more investment to prevent mental health issues, and preventing alcohol and drug use disorders from developing in the first place.

Early intervention and treatment of mental illness, trauma and drug use is important. Okrasiuk/Shutterstock Preventing trauma from occuring and supporting those exposed is crucial to end what can often become a vicious cycle of intergenerational trauma and violence. Safe and supportive environments and relationships can protect children against mental health problems or further violence as they grow up and engage in their own intimate relationships.

We also need to acknowledge the widespread impact of trauma and its effects on mental health, drug use and violence. This needs to be integrated into policies and practices to reduce re-traumatising individuals.

How about programs for perpetrators?

Most existing standard intervention programs for perpetrators do not consider the links between trauma, mental health and perpetrating intimate partner violence. Such programs tend to have little or mixed effects on the behaviour of perpetrators.

But we could improve these programs with a coordinated approach including treating mental illness, drug use and trauma at the same time.

Such “multicomponent” programs show promise in meaningfully reducing violent behaviour. However, we need more rigorous and large-scale evaluations of how well they work.

What needs to happen next?

Supporting victim-survivors and improving interventions for perpetrators are both needed. However, intervening once violence has occurred is arguably too late.

We need to direct our efforts towards broader, holistic approaches to prevent and reduce intimate partner violence, including addressing the underlying contributors to violence we’ve outlined.

We also need to look more widely at preventing intimate partner violence and gendered violence.

We need developmentally appropriate education and skills-based programs for adolescents to prevent the emergence of unhealthy relationship patterns before they become established.

We also need to address the social determinants of health that contribute to violence. This includes improving access to affordable housing, employment opportunities and accessible health-care support and treatment options.

All these will be critical if we are to break the cycle of intimate partner violence and improve outcomes for victim-survivors.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. In an emergency, call 000.

Siobhan O’Dean, Postdoctoral Research Associate, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney; Lucinda Grummitt, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney, and Steph Kershaw, Research Fellow, The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Can a child legally take puberty blockers? What if their parents disagree?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Young people’s access to gender-affirming medical care has been making headlines this week.

Today, federal Health Minister Mark Butler announced a review into health care for trans and gender-diverse children and adolescents. The National Health and Medical Research Council will conduct the review.

Yesterday, The Australian published an open letter to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese calling for a federal inquiry, and a nationwide pause on puberty blockers and hormone therapy for minors.

This followed Queensland Health Minister Tim Nicholls earlier this week announcing an immediate pause on access to puberty blockers and hormone therapies for new patients under 18 in the state’s public health system, pending a review.

In the United States, President Donald Trump signed an executive order this week directing federal agencies to restrict access to gender-affirming care for anyone under 19.

This recent wave of political attention might imply gender-affirming care for young people is risky, controversial, perhaps even new.

But Australian courts have already extensively tested questions about its legitimacy, the conditions under which it can be provided, and the scope and limits of parental powers to authorise it.

MirasWonderland/Shutterstock What are puberty blockers?

Puberty blockers suppress the release of oestrogen and testosterone, which are primarily responsible for the physical changes associated with puberty. They are generally safe and used in paediatric medicine for various conditions, including precocious (early) puberty, hormone disorders and some hormone-sensitive cancers.

International and domestic standards of care state that puberty blockers are reversible, non-harmful, and can prevent young people from experiencing the distress of undergoing a puberty that does not align with their gender identity. They also give young people time to develop the maturity needed to make informed decisions about more permanent medical interventions further down the line.

Puberty blockers are one type of gender-affirming care. This care includes medical, psychological and social interventions to support transgender, gender-diverse and, in some cases, intersex people.

Young people in Australia need a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria to receive this care. Gender dysphoria is defined as the psychological distress that can arise when a person’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth. This diagnosis is only granted after an exhaustive and often onerous medical assessment.

After a diagnosis, treatment may involve hormones such as oestrogen or testosterone and/or puberty-blocking medications.

Hormone therapies involving oestrogen and testosterone are only prescribed in Australia once a young person has been deemed capable of giving informed consent, usually around the age of 16. For puberty blockers, parents can consent at a younger age.

Gender dysphoria comes with considerable psychological distress. slexp880/Shutterstock Can a child legally access puberty blockers?

Gender-affirming care has been the subject of extensive debate in the Family Court of Australia (now the Federal Circuit and Family Court).

Between 2004 and 2017, every minor who wanted to access gender-affirming care had to apply for a judge to approve it. However, medical professionals, human rights organisations and some judges condemned this process.

In research for my forthcoming book, I found the Family Court has heard at least 99 cases about a young person’s gender-affirming care since 2004. Across these cases, the court examined the potential risks of gender-affirming treatment and considered whether parents should have the authority to consent on their child’s behalf.

When determining whether parents can consent to a particular medical procedure for their child, the court must consider whether the treatment is “therapeutic” and whether there is a significant risk of a wrong decision being made.

However, in a landmark 2017 case, the court ruled that judicial oversight was not required because gender-affirming treatments meet the standards of normal medical care.

It reasoned that because these therapies address an internationally recognised medical condition, are supported by leading professional medical organisations, and are backed by robust clinical research, there is no justification for treating them differently from any other standard medical intervention. These principles still stand today.

What if parents disagree?

Sometimes parents disagree with decisions about gender-affirming care made by their child, or each other.

As with all forms of health care, under Australian law, parents and legal guardians are responsible for making medical decisions on behalf of their children. That responsibility usually shifts once those children reach a sufficient age and level of maturity to make their own decisions.

However, in another landmark case in 2020, the court ruled gender-affirming treatments cannot be given to minors without consent from both parents, even if the child is capable of providing their own consent. This means that if there is any disagreement among parents and the young person about either their capacity to consent or the legitimacy of the treatment, only a judge can authorise it.

In such instances, the court must assess whether the proposed treatment is in the child’s best interests and make a determination accordingly. Again, these principals apply today.

If a parent disagrees with their child, the matter can go to court. PeopleImages.com – Yuri A/Shutterstock Have the courts ever denied care?

Across the at least 99 cases the court has heard about gender-affirming care since 2004, 17 have involved a parent opposing the treatment and one has involved neither parent supporting it.

Regardless of parental support, in every case, the court has been responsible for determining whether gender-affirming treatment was in the child’s best interests. These decisions were based on medical evidence, expert testimony, and the specific circumstances of the young person involved.

In all cases bar one, the court has found overwhelming evidence to support gender-affirming care, and approved it.

Supporting transgender young people

The history of Australia’s legal debates about gender-affirming care shows it has already been the subject of intense legal and medical scrutiny.

Gender-affirming care is already difficult for young people to access, with many lacking the parental support required or facing other barriers to care.

Gender-affirming care is potentially life-saving, or at the very least life-affirming. It almost invariably leads to better social and emotional outcomes. Further restricting access is not the “protection” its opponents claim.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. For LGBTQIA+ peer support and resources, you can also contact Switchboard, QLife (call 1800 184 527), Queerspace, Transcend Australia (support for trans, gender-diverse, and non-binary young people and their families) or Minus18 (resources and community support for LGBTQIA+ young people).

Matthew Mitchell, Lecturer in Criminology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What is PNF stretching, and will it improve my flexibility?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Whether improving your flexibility was one of your new year’s resolutions, or you’ve been inspired watching certain tennis stars warming up at the Australian Open, maybe 2025 has you keen to focus on regular stretching.

However, a quick Google search might leave you overwhelmed by all the different stretching techniques. There’s static stretching and dynamic stretching, which can be regarded as the main types of stretching.

But there are also some other potentially lesser known types of stretching, such as PNF stretching. So if you’ve come across PNF stretching and it piques your interest, what do you need to know?

Undrey/Shutterstock What is PNF stretching?

PNF stretching stands for proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. It was developed in the 1940s in the United States by neurologist Herman Kabat and physical therapists Margaret Knott and Dorothy Voss.

PNF stretching was initially designed to help patients with neurological conditions that affect the movement of muscles, such as polio and multiple sclerosis.

By the 1970s, its popularity had seen PNF stretching expand beyond the clinic and into the sporting arena where it was used by athletes and fitness enthusiasts during their warm-up and to improve their flexibility.

Although the specifics have evolved over time, PNF essentially combines static stretching (where a muscle is held in a lengthened position for a short period of time) with isometric muscle contractions (where the muscle produces force without changing length).

PNF stretching is typically performed with the help of a partner.

There are 2 main types

The two most common types of PNF stretching are the “contract-relax” and “contract-relax-agonist-contract” methods.

The contract-relax method involves putting a muscle into a stretched position, followed immediately by an isometric contraction of the same muscle. When the person stops contracting, the muscle is then moved into a deeper stretch before the process is repeated.

For example, to improve your hamstring flexibility, you could lie down and get a partner to lift your leg up just to the point where you begin to feel a stretch in the back of your thigh.

Once this sensation eases, attempt to push your leg back towards the ground as your partner resists the movement. After this, your partner should now be able to lift your leg up slightly higher than before until you feel the same stretching sensation.

This technique was based on the premise that the contracted muscle would fall “electrically silent” following the isometric contraction and therefore not offer its usual level of resistance to further stretching (called “autogenic inhibition”). The contract-relax method attempts to exploit this brief window to create a deeper stretch than would otherwise be possible without the prior muscle contraction.

The contract-relax-agonist-contract method is similar. But after the isometric contraction of the stretched muscle, you perform an additional contraction of the muscle group opposing the muscle being stretched (referred to as the “agonist” muscle), before the muscle is moved into a static stretch once more.

Again, if you’re trying to improve hamstring flexibility, immediately after trying to push your leg towards the ground you would attempt to lift it back towards the ceiling (this bit without partner resistance). You would do this by contracting the muscles on the front of the thigh (the quadriceps, the agonist muscle in this case).

Likewise, after this, your partner should be able to lift your leg up slightly higher than before.

The contract-relax-agonist-contract method is said to take advantage of a phenomenon known as “reciprocal inhibition.” This is where contracting the muscle group opposite that of the muscle being stretched leads to a short period of reduced activation of the stretched muscle, allowing the muscle to stretch further than normal.

What does the evidence say?

Research has shown PNF stretching is associated with improved flexibility.

While it has been suggested that both PNF methods improve flexibility via changes in nervous system function, research suggests they may simply improve our ability to tolerate stretching.

It’s worth noting most of the research on PNF stretching and flexibility has focused on healthy populations. This makes it difficult to provide evidence-based recommendations for people with clinical conditions.

And it may not be the most effective method if you’re looking to improve your flexibility in the long term. A 2018 review found static stretching was better for improving flexibility compared to PNF stretching. But other research has found it could offer greater immediate benefits for flexibility than static stretching.

At present, similar to other types of stretching, research linking PNF stretching to injury prevention and improved athletic performance is relatively inconclusive.

PNF stretching may actually lead to small temporary deficits in performance of strength, power, and speed-based activities if performed immediately beforehand. So it’s probably best done after exercise or as a part of a standalone flexibility session.

Static stretching may be a more effective way to improve flexibility over the long-term. GaudiLab/Shutterstock How much should you do?

It appears that a single contract-relax or contract-relax-agonist-contract repetition per muscle, performed twice per week, is enough to improve flexibility.

The contraction itself doesn’t need to be hard and forceful – only about 20% of your maximal effort should suffice. The contraction should be held for at least three seconds, while the static stretching component should be maintained until the stretching sensation eases.

So PNF stretching is potentially a more time-efficient way to improve flexibility, compared to, for example, static stretching. In a recent study we found four minutes of static stretching per muscle during a single session is optimal for an immediate improvement in flexibility.

Is PNF stretching the right choice for me?

Providing you have a partner who can help you, PNF stretching could be a good option. It might also provide a faster way to become more flexible for those who are time poor.

However, if you’re about to perform any activities that require strength, power, or speed, it may be wise to limit PNF stretching to afterwards to avoid any potential deficits in performance.

Lewis Ingram, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of South Australia and Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How To Prevent And Reverse Type 2 Diabetes

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Turn back the clock on insulin resistance

This is Dr. Jason Fung. He’s a world-leading expert on intermittent fasting and low carbohydrate approaches to diet. He also co-founded the Intensive Dietary Management Program, later rebranded to the snappier title: The Fasting Method, a program to help people lose weight and reverse type 2 diabetes. Dr. Fung is certified with the Institute for Functional Medicine, for providing functional medicine certification along with educational programs directly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME).

Why Intermittent Fasting?

Intermittent fasting is a well-established, well-evidenced, healthful practice for most people. In the case of diabetes, it becomes complicated, because if one’s blood sugars are too low during a fasting period, it will need correcting, thus breaking the fast.

Note: this is about preventing and reversing type 2 diabetes. Type 1 is very different, and sadly cannot be prevented or reversed in this fashion.

However, these ideas may still be useful if you have T1D, as you have an even greater need to avoid developing insulin resistance; you obviously don’t want your exogenous insulin to stop working.

Nevertheless, please do confer with your endocrinologist before changing your dietary habits, as they will know your personal physiology and circumstances in ways that we (and Dr. Fung) don’t.

In the case of having type 2 diabetes, again, please still check with your doctor, but the stakes are a lot lower for you, and you will probably be able to fast without incident, depending on your diet itself (more on this later).

Intermittent Fasting can be extra helpful for the body in the case of type 2 diabetes, as it helps give the body a rest from high insulin levels, thus allowing the body to become gradually re-sensitised to insulin.

Why low carbohydrate?

Carbohydrates, especially sugars, especially fructose*, cause excess sugar to be quickly processed by the liver and stored there. When the body’s ability to store glycogen is exceeded, the liver stores energy as fat instead. The resultant fatty liver is a major contributor to insulin resistance, when the liver can’t keep up with the demand; the blood becomes spiked full of unprocessed sugars, and the pancreas must work overtime to produce more and more insulin to deal with that—until the body starts becoming desensitized to insulin. In other words, type 2 diabetes.

There are other factors that affect whether we get type 2 diabetes, for example a genetic predisposition. But, our carb intake is something we can control, so it’s something that Dr. Fung focuses on.

*A word on fructose: actual fruits are usually diabetes-neutral or a net positive due to their fiber and polyphenols.

Fructose as an added ingredient, however, not so much. That stuff zips straight into your veins with nothing to slow it down and nothing to mitigate it.

The advice from Dr. Fung is simple here: cut the carbs. If you are already diabetic and do this with no preparation, you will probably simply suffer hypoglycemia, so instead:

- Enjoy a fibrous starter (a salad, some fruit, or perhaps some nuts)

- Load up with protein first, during your main meal—this will start to trigger your feelings of satedness

- Eat carbs last (preferably whole, unprocessed carbohydrates), and stop eating when 80% full.

Adapting Intermittent Fasting to diabetes

Dr. Fung advocates for starting small, and gradually increasing your fasting period, until, ideally, fasting 16 hours per day. You probably won’t be able to do this immediately, and that’s fine.

You also probably won’t be able to do this, if you don’t also make the dietary adjustments that help to give your liver a break, and thus by knock-on-effect, give your pancreas a break too.

With the dietary adjustments too, however, your insulin production-and-response will start to return to its pre-diabetic state, and finally its healthy state, after which, it’s just a matter of maintenance.

Want to hear more from Dr. Fung?

You may enjoy his blog, and for those who like videos, here is his YouTube channel:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Salt Fix – by Dr. James DiNicolantonio

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book has a bold premise: high salt consumption is not, as global scientific consensus holds, a serious health risk, but rather, as the title suggests, a health fix.

Dr. DiNicolantonio, a pharmacist, explains how “our ancestors crawled out of the sea millions of years ago and we still crave that salt”, giving this as a reason why we should consume salt ad libitum, aiming for 8–10g per day, and thereafter a fair portion of the book is given over to discussing how many health conditions are caused/exacerbated by sugar, and that therefore we have demonized the wrong white crystal (scientific consensus is that there are many white crystals that can cause us harm).

Indeed, sugar can be a big health problem, but reading it at such length felt a lot like when all a politician can talk about is how their political rival is worse.

A lot of the studies the author cites to support the idea of healthy higher salt consumption rates were on non-human animals, and it’s always a lottery as to whether those results translate to humans or not. Also, many of the studies he’s citing are old and have methodological flaws, while others we could not find when we looked them up.

One of the sources cited is “my friend Jose tried this and it worked for him”.

Bottom line: sodium is an essential mineral that we do need to live, but we are not convinced that this book’s ideas have scientific merit. But are they well-argued? Also no.

Click here to check out The Salt Fix for yourself! It’s a fascinating book.

(Usually, if we do not approve of a book, we simply do not review it. We like to keep things positive. However, this one came up in Q&A, so it seemed appropriate to share our review. Also, the occasional negative review may reassure you, dear readers, that when we praise a book, we mean it)

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: