Taurine: An Anti-Aging Powerhouse? Exploring Its Unexpected Benefits

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Mark Rosenberg explains:

Not a stimulant, but…

- Its presence in energy drinks often causes people to assume it’s a stimulant, but it’s not. In fact, it’s a GABA-agonist, thus having a calming effect.

- The real reason it’s in energy drinks is because it helps increase mitochondrial ATP production (ATP = adenosine triphosphate = how cells store energy that’s ready to use; mitochondria take glucose and make ATP)

- Taurine is also anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer.

- In the category of aging, human studies are slow to give results for obvious reasons, but mouse studies show that supplementing taurine in middle-aged mice increased their lifespan by 10–12%, as well as improving various physiological markers of aging.

- Taking a closer look at aging—literally; looking at cellular aging—taurine reduces cellular senescence and protects telomeres, thus decreasing DNA mutations.

For more on the science of these, plus Dr. Rosenberg’s personal experience, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Taurine’s Benefits For Heart Health And More

- Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight

- Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Daily, Weekly, Monthly: Habits Against Aging

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Anil Rajani has advice on restoring/retaining youthfulness. Two out of three of the sections are on skincare specifically, which may seem a vanity, but it’s also worth remembering that our skin is a very large and significant organ, and makes a big difference for the rest of our physical health, as well as our mental health. So, it’s worthwhile to look after it:

The recommendations

Daily: meditation practice

Meditation reduces stress, which reduction in turn protects telomere length, slowing the overall aging process in every living cell of the body.

Weekly: skincare basics

Dr. Rajani recommends a combination of retinol and glycolic acid. The former to accelerate cell turnover, stimulate collagen production, and reduce wrinkles; the latter, to exfoliate dead cells, allowing the retinol to do its job more effectively.

We at 10almonds would like to add: wearing sunscreen with SPF50 is a very good thing to do on any day that your phone’s weather app says the UV index is “moderate” or higher.

Monthly: skincare extras

Here are the real luxuries; spa visits, microneedling (stimulates collagen production), and non-ablative laser therapy. He recommends creating a home spa if possible for monthly skincare treatments, investing in high-quality devices for long-term benefits.

For more on all of these things, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

- No-Frills, Evidence-Based Mindfulness

- The Evidence-Based Skincare That Beats Product-Specific Hype

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Migraine Mythbusting

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Migraine: When Headaches Are The Tip Of The Neurological Iceberg

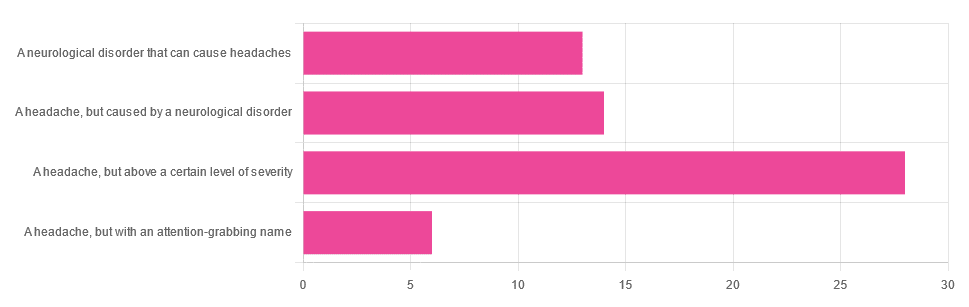

Yesterday, we asked you “What is a migraine?” and got the above-depicted, below-described spread of responses:

- Just under 46% said “a headache, but above a certain level of severity”

- Just under 23% said “a headache, but caused by a neurological disorder”

- Just over 21% said “a neurological disorder that can cause headaches”

- Just under 10% said “a headache, but with an attention-grabbing name”

So… What does the science say?

A migraine is a headache, but above a certain level of severity: True or False?

While that’s usually a very noticeable part of it… That’s only one part of it, and not a required diagnostic criterion. So, in terms of defining what a migraine is, False.

Indeed, migraine may occur without any headache, let alone a severe one, for example: Abdominal Migraine—though this is much less well-researched than the more common with-headache varieties.

Here are the defining characteristics of a migraine, with the handy mnemonic 5-4-3-2-1:

- 5 or more attacks

- 4 hours to 3 days in duration

- 2 or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affects only one side of the head)

- Pulsating

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Worsened by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

- 1 or more of the following:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to both light and sound

Source: Cephalalgia | ICHD-II Classification: Parts 1–3: Primary, Secondary and Other

As one of our subscribers wrote:

❝I have chronic migraine, and it is NOT fun. It takes away from my enjoyment of family activities, time with friends, and even enjoying alone time. Anyone who says a migraine is just a bad headache has not had to deal with vertigo, nausea, loss of balance, photophobia, light sensitivity, or a host of other symptoms.❞

Migraine is a neurological disorder: True or False?

True! While the underlying causes aren’t known, what is known is that there are genetic and neurological factors at play.

❝Migraine is a recurrent, disabling neurological disorder. The World Health Organization ranks migraine as the most prevalent, disabling, long-term neurological condition when taking into account years lost due to disability.

Considerable progress has been made in elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine, associated genetic factors that may influence susceptibility to the disease❞

Source: JHP | Mechanisms of migraine as a chronic evolutive condition

Migraine is just a headache with a more attention-grabbing name: True or False?

Clearly, False.

As we’ve already covered why above, we’ll just close today with a nod to an old joke amongst people with chronic illnesses in general:

“Are you just saying that because you want attention?”

“Yes… Medical attention!”

Want to learn more?

You can find a lot of resources at…

NIH | National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke | Migraine

and…

The Migraine Trust ← helpfully, this one has a “Calm mode” to tone down the colorscheme of the website!

Particularly useful from the above site are its pages:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

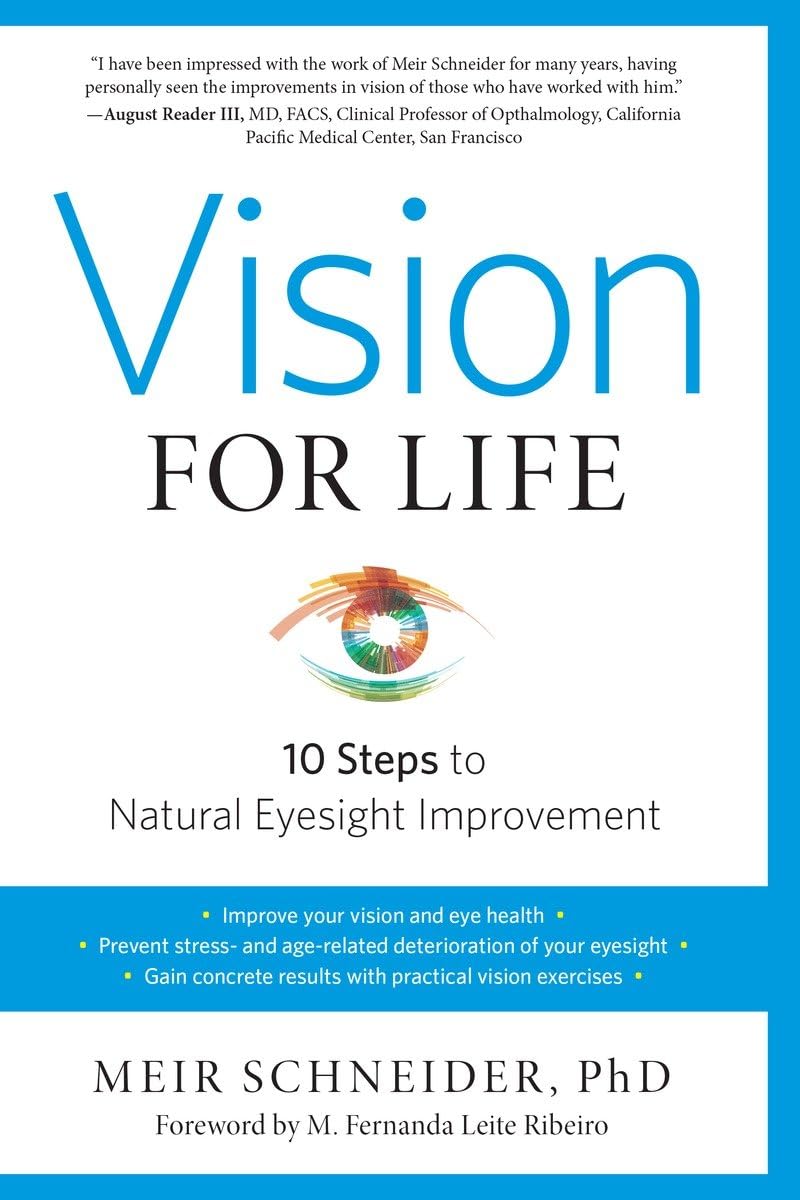

Vision for Life, Revised Edition – by Dr. Meir Schneider

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The “ten steps” would be better called “ten exercises”, as they’re ten things that one can (and should) continue to do on an ongoing basis, rather than steps to progress through and then forget about.

We can’t claim to have tested the ten exercises for improvement (this reviewer has excellent eyesight and merely hopes to maintain such as she gets older) but the rationale is compelling, and the public testimonials abundant.

Dr. Schneider also talks about improving and correcting errors of refraction—in other words, doing the job of any corrective lenses you may currently be using. While he doesn’t claim miracles, it turns out there is a lot that can be done for common issues such as near-sightedness and far-sightedness, amongst others.

There’s a large section on managing more chronic pathological eye conditions than this reviewer previously knew existed; in some cases it’s a matter of making sure things don’t get worse, but in many others, there’s a recurring of theme of “and here’s an exercise for correcting that”.

The writing style is a little more “narrative prose” than we’d have liked, but the quality of the content more than makes up for any style preference issues.

Bottom line: the human body is a highly adaptive organism, and sometimes it just needs a little help to correct itself. This book can help with that.

Click here to check out Vision for Life, and take good care of yours!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Pink Himalayan Salt: Health Facts

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Q: Great article about the health risks of salt to organs other than the heart! Is pink Himalayan sea salt, the pink kind, healthier?

Thank you! And, no, sorry. Any salt that is sodium chloride has the exact same effect because it’s chemically the same substance, even if impurities (however pretty) make it look different.

If you want a lower-sodium salt, we recommend the kind that says “low sodium” or “reduced sodium” or similar. Check the ingredients, it’ll probably be sodium chloride cut with potassium chloride. Potassium chloride is not only not a source of sodium, but also, it’s a source of potassium, which (unlike sodium) most of us could stand to get a little more of.

For your convenience: here’s an example on Amazon!

Bonus: you can get a reduced sodium version of pink Himalayan salt too!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Xylitol vs Erythritol – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing xylitol to erythritol, we picked the xylitol.

Why?

They’re both sugar alcohols, which so far as the body is concerned are neither sugars nor alcohols in the way those words are commonly understood; it’s just a chemical term. The sugars aren’t processed as such by the body and are passed as dietary fiber, and nor is there any intoxicating effect as one might expect from an alcohol.

In terms of macronutrients, while technically they both have carbs, for all functional purposes they don’t and just have a little fiber.

In terms of micronutrients, they don’t have any.

The one thing that sets them apart is their respective safety profiles. Xylitol is prothrombotic and associated with major adverse cardiac events (CI=95, adjusted hazard ratio=1.57, range=1.12-2.21), while erythritol is also prothrombotic and more strongly associated with major adverse cardiac events (CI=95, adjusted hazard ratio=2.21, range=1.20-4.07).

So, xylitol is bad and erythritol is worse, which means the relatively “healthier” is xylitol. We don’t recommend either, though.

Studies for both:

- Xylitol is prothrombotic and associated with cardiovascular risk

- The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk

Links for the specific products we compared, in case our assessment hasn’t put you off them:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- The WHO’s New View On Sugar-Free Sweeteners ← the WHO’s advice is “don’t”

- Stevia vs Acesulfame Potassium – Which is Healthier? ← stevia’s pretty much the healthiest artificial sweetener around, though, if you’re going to use one

- The Fascinating Truth About Aspartame, Cancer, & Neurotoxicity ← under the cold light of science, aspartame isn’t actually as bad as it was painted a few decades ago, mostly by a viral hoax letter. Per the WHO’s advice, it’s still good to avoid sweeteners in general, however.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Own Your Past Change Your Future – by Dr. John Delony

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one is exactly what it says on the cover. It’s reminiscent in its premise of the more clinically-presented Tell Yourself A Better Lie (an excellent book, which we reviewed previously) but this time presented in a much more casual fashion.

Dr. Delony favors focusing on telling stories, and indeed this book contains many anecdotes. But also he bids the reader to examine our own stories—those we tell ourselves about ourselves, our past, people around us, and so forth.

To call those things “stories” may create a knee-jerk response of feeling like it is an accusation of dishonesty, but rather, it is acknowledging that experiences are subjective, and our framing of narratives can vary.

As for reframing things and taking control, his five-step-plan for doing such is:

- Acknowledge reality

- Get connected

- Change your thoughts

- Change your actions

- Seek redemption

…which each get a chapter devoted to them in the book.

You may notice that these are very similar to some of the steps in 12-step programs, and also some religious groups and/or self-improvement groups. In other words, this may not be the most original approach, but it is a tried-and-tested one.

Bottom line: if you feel like your life needs an overhaul, but don’t want to wade through a bunch of psychology to do it, then this book could be it for you.

Click here to check out Own Your Past To Change Your Future, and do just that!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: