Quinoa vs Couscous – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing quinoa to couscous, we picked the quinoa.

Why?

Firstly, quinoa is the least processed by far. Couscous, even if wholewheat, has by necessity been processed to make what is more or less the same general “stuff” as pasta. Now, the degree to which something has or has not been processed is a common indicator of healthiness, but not necessarily declarative. There are some processed foods that are healthy (e.g. many fermented products) and there are some unprocessed plant or animal products that can kill you (e.g. red meat’s health risks, or the wrong mushrooms). But in this case—quinoa vs couscous—it’s all borne out pretty much as expected.

For the purposes of the following comparisons, we’ll be looking at uncooked/dry weights.

In terms of macros, quinoa has a little more protein, slightly lower carbs, and several times the fiber. The amino acids making up quinoa’s protein are also much more varied.

In the category of vitamins, quinoa has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, and B9, while couscous boasts a little more of vitamins B3 and B5. Given the respective margins of difference, as well as the total vitamins contained, this category is an easy win for quinoa.

When it comes to minerals, this one’s not even more clear. Quinoa has a lot more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Couscous, meanwhile has more of just one mineral: sodium. So, maybe not one you want more of.

All in all, today’s is an easy pick: quinoa!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Carbohydrate Mythbusting: Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

- What’s The Real Deal With The Paleo Diet?

- Gluten Mythbusting: What’s The Truth? ← we didn’t mention it above, but couscous is by default gluten-free, and couscous, being made of wheat, is by default not gluten-free, which may be another reason for some to choose quinoa

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

When Doctors Make House Calls, Modern-Style!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

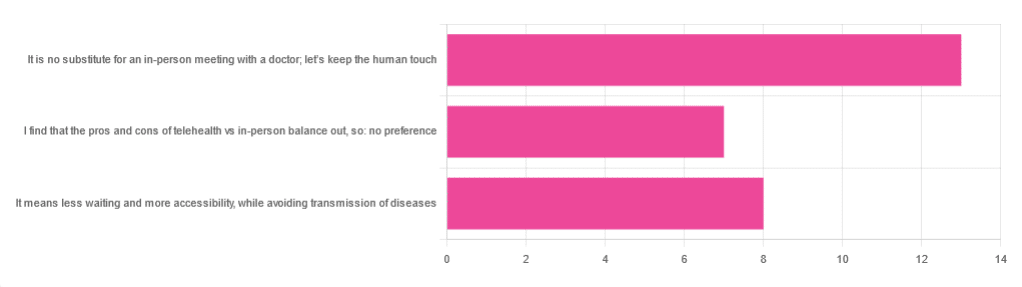

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you foryour opinion of telehealth for primary care consultations*, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 46% said “It is no substitute for an in-person meeting with a doctor; let’s keep the human touch”

- About 29% said “It means less waiting and more accessibility, while avoiding transmission of diseases”

- And 25 % said “I find that the pros and cons of telehealth vs in-person balance out, so: no preference”

*We specified that by “primary care” we mean the initial consultation with a non-specialist doctor, before receiving treatment or being referred to a specialist. By “telehealth” we mean by videocall or phonecall.

So, what does the science say?

A quick note first

Because telehealth was barely a thing (statistically speaking) before the first stages of the COVID pandemic, compared to how it is now, most of the science for this is young, and a lot of the science simply hasn’t been done yet, and/or has not been published yet, because the process can take years.

Because of this, some studies we do have aren’t specifically about primary care, and are sometimes about specialists. We think this should not affect the results much, but it bears highlighting.

Nevertheless, we’ll do what we can with the science we have!

Telehealth is more accessible than in-person consultations: True or False?

True, for most people. For example…

❝Data was found from a variety of emergency and non-emergency departments of primary, secondary, and specialised healthcare.

Satisfaction was high among recipients of healthcare, scoring 9-10 on a scale of 0-10 or ranging from 73.3% to 100%.

Convenience was rated high in every specialty examined. Satisfaction of clinicians was high throughout the specialities despite connection failure and concerns about confidentiality of information.❞

whereas…

❝Nonetheless, studies reported perception of increased barriers to accessing care and inequalities for vulnerable patients especially in older people❞

~ Ibid.

Source: Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review

Now, perception of those things does necessarily equate to an actual increased barrier, but it is reasonable that someone who thinks something is inaccessible will be less inclined to try to access it.

The quality of care provided via telehealth is as good as in-person: True or False?

True, ostensibly, with caveats. The caveats are:

- We’re going offreported patient satisfaction, not objective patient health outcomes (we found little* science as yet for the relative incidence of misdiagnosis, for example—which kind of thing will take time to be revealed).

- We’re also therefore speaking (as statistics do) for the significant majority of people. However, if we happen to be (statistically speaking) an insignificant minority, well, that just sucks for us personally.

*we did find some, but it wasn’t very helpful yet. For example:

An electronic trigger to detect telemedicine-related diagnostic errors

this one does look at the incidence of diagnostic errors, but provides no control group (i.e. otherwise-comparable in-person consultations) for comparison.

While most oft-considered demographic groups reported comparable patient satisfaction (per race, gender, and socioeconomic status, for example), there was one outlier variable, which was age (as we quoted from that first study above).

However!

Looking under the hood of these stats, it seems that age is not the real culprit, so much as technological illiteracy, which is heavily correlated with age:

❝Lower eHealth literacy is associated with more negative attitudes towards I/C technology in healthcare. This trend is consistent across diverse demographics and regions. ❞

Source: Meta-analysis: eHealth literacy and attitudes towards internet/computer technology

There are things that can be done at an in-person consultation that can’t be done by telehealth: True or False?

True, of course. It is incredibly rare that we will cite “common sense”, (as sometimes “common sense” is actually “common mistakes” and is simply and verifiably wrong), but in this case, as one 10almonds subscriber put it:

❝The doctor uses his five senses to assess. This cannot be attained over the phone❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

A quick note first: if your doctor is using their sense of taste to diagnose you, please get a different doctor, because they should definitely not be doing that!

Not in this century, anyway… Once upon a time, diabetes was diagnosed by urine-tasting (and yes, that was a fairly reliable method).

However, nowadays indeed a doctor will use sight, sound, touch, and sometimes even smell.

In a videocall we’re down to two of those senses (sight and sound), and in a phonecall, down to one (sound) and even that is hampered. Your doctor cannot, for example, use a stethoscope over the phone.

With this in mind, it really comes down to what you need from your doctor in that consultation.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is to be prescribed an antidepressant, that probably doesn’t need a full physical.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is a referral, chances are that’ll be fine by telehealth too.

- If your doctor is 99% sure that what you need is a verbal check-up (e.g. “How’s it been going for you, with the medication that I prescribed for you a month ago?”, then again, a call is probably fine.

If you have a worrying lump, or an unhappy bodily discharge, or an unexplained mysterious pain? These things, more likely an in-person check-up is in order.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck – by Mark Manson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may wonder from the title: is this book arguing that we should all be callous heartless monsters? And no, it is not.

Instead, author Mark Manson advocates for cynicism, but less in the manner of Scrooge, and more in the manner of Diogenes:

- That life will involve struggle, so we might as well at least choose our struggles.

- That we will make mistakes, so we might as well accept them as learning experiences.

- That we will love and we will lose, so we might as well do it right while we can.

In short, the book is less about not caring… And more about caring about the right things only.

So, what are “the right things”? Manson bids us decide for ourselves, but certainly has ideas and pointers, with regard to what may or may not be healthy values to pursue.

The style throughout is casual and almost conversational, without being overly padded. It makes for very easy reading.

If the book has a weak point, it’s that when it briefly makes a suprisingly prescriptive turn into recommending we take up Buddhism, it may feel a bit like our friend who wants us to join in the latest MLM scheme. But, he’s soon back on track.

Bottom line: if you ever find yourself stressed with living up to unwanted expectations—your own, other people’s, and society’s—this book can really help streamline things.

Share This Post

-

How Much Can Hypnotherapy Really Do?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sit Back, Relax, And…

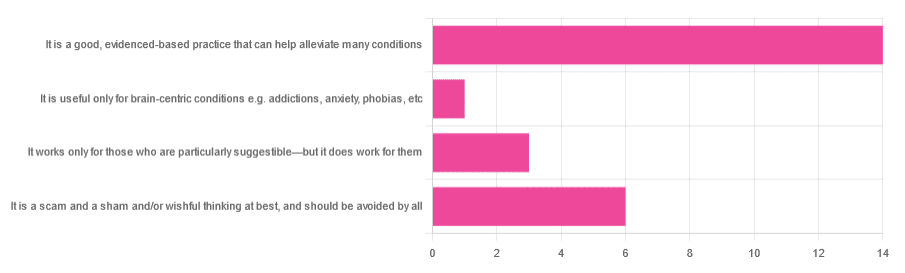

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinions of hypnotherapy, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 58% said “It is a good, evidenced-based practice that can help alleviate many conditions”

- Exactly 25% said “It is a scam and sham and/or wishful thinking at best, and should be avoided by all”

- About 13% said “It works only for those who are particularly suggestible—but it does work for them”

- One (1) person said “It is useful only for brain-centric conditions e.g. addictions, anxiety, phobias, etc”

So what does the science say?

Hypnotherapy is all in the patient’s head: True or False?

True! But guess which part of your body controls much of the rest of it.

So while hypnotherapy may be “all in the head”, its effects are not.

Since placebo effect, nocebo effect, and psychosomatic effect in general are well-documented, it’s quite safe to say at the very least that hypnotherapy thus “may be useful”.

Which prompts the question…

Hypnotherapy is just placebo: True or False?

False, probably. At the very least, if it’s placebo, it’s an unusually effective placebo.

And yes, even though testing against placebo is considered a good method of doing randomized controlled trials, some placebos are definitely better than others. If a placebo starts giving results much better than other placebos, is it still a placebo? Possibly a philosophical question whose answer may be rooted in semantics, but happily we do have a more useful answer…

Here’s an interesting paper which: a) begins its abstract with the strong, unequivocal statement “Hypnosis has proven clinical utility”, and b) goes on to examine the changes in neural activity during hypnosis:

Brain Activity and Functional Connectivity Associated with Hypnosis

It works only for the very suggestible: True or False?

False, broadly. As with any medical and/or therapeutic procedure, a patient’s expectations can affect the treatment outcome.

And, especially worthy of note, a patient’s level of engagement will vastly affect it treatment that has patient involvement. So for example, if a doctor prescribes a patient pills, which the patient does not think will work, so the patient takes them intermittently, because they’re slow to get the prescription refilled, etc, then surprise, the pills won’t get as good results (since they’re often not being taken).

How this plays out in hypnotherapy: because hypnotherapy is a guided process, part of its efficacy relies on the patient following instructions. If the hypnotherapist guides the patient’s mind, and internally the patient is just going “nope nope nope, what a lot of rubbish” then of course it will not work, just like if you ask for directions in the street and then ignore them, you won’t get to where you want to be.

For those who didn’t click on the above link by the way, you might want to go back and have a look at it, because it included groups of individuals with “high/low hypnotizability” per several ways of scoring such.

It works only for brain-centric things, e.g. addictions, anxieties, phobias, etc: True or False?

False—but it is better at those. Here for example is the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists’ information page, and if you go to “What conditions can hypnotherapy help to treat”, you’ll see two broad categories; the first is almost entirely brain-stuff; the second is more varied, and includes pain relief of various kinds, burn care, cancer treatment side effects, and even menopause symptoms. Finally, warts and other various skin conditions get their own (positive) mention, per “this is possible through the positive effects hypnosis has on the immune system”:

RCPsych | Hypnosis And Hypnotherapy

Wondering how much psychosomatic effect can do?

You might like this previous article; it’s not about hypnotherapy, but it is about the difference the mind can make on physical markers of aging:

Aging, Counterclockwise: When Age Is A Flexible Number

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Acid Reflux After Meals? Here’s How To Stop It Naturally

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Harvard-trained gastroenterologist Dr. Saurabh Sethi advises:

Calming it down

First of all, what it actually is and how it happens: acid reflux occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) doesn’t close properly, allowing stomach acid to flow back into the esophagus. Chronic acid reflux is known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Symptoms can include heartburn, an acid taste in the mouth, belching, bloating, sore throat, and a persistent cough—but most people do not get all of the symptoms, usually just some.

Things that help it acutely (as in, you can do them today and they will help today): consider skipping certain foods/substances like peppermint, tomatoes, chocolate, alcohol, and caffeine, which can worsen acid reflux. Eating smaller, more frequent meals instead of large ones and leaving a gap of 3–4 hours before lying down after meals can also help manage symptoms.

Things that can help it chronically (as in, you do them in an ongoing fashion and they will help in an ongoing fashion): lifestyle changes like quitting smoking, reducing alcohol intake, and wearing loose clothing can strengthen the LES. Maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding large meals, especially close to bedtime, can also reduce symptoms. Elevating the upper body while sleeping (using a wedge pillow or raising the bed by 10–20°) can make a big difference.

Medications to avoid, if possible, include: aspirin, ibuprofen, and calcium channel blockers.

Some drinks you can enjoy that will help: drinking water can quickly dilute stomach acid and provide relief. Herbal teas like basil tea, fennel tea, and ginger tea are also effective. But notably: not peppermint tea! Since, as mentioned earlier, peppermint is a known trigger for acid reflux (despite peppermint’s usual digestion-improving properties).

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Coughing/Wheezing After Dinner? Here’s How To Fix It ← this is about acid reflux and more

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mosquitoes can spread the flesh-eating Buruli ulcer. Here’s how you can protect yourself

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Each year, more and more Victorians become sick with a flesh-eating bacteria known as Buruli ulcer. Last year, 363 people presented with the infection, the highest number since 2004.

But it has been unclear exactly how it spreads, until now. New research shows mosquitoes are infected from biting possums that carry the bacteria. Mozzies spread it to humans through their bite.

What is Buruli ulcer?

Buruli ulcer, also known as Bairnsdale ulcer, is a skin infection caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans.

It starts off like a small mosquito bite and over many months, slowly develops into an ulcer, with extensive destruction of the underlying tissue.

While often painless initially, the infection can become very serious. If left untreated, the ulcer can continue to enlarge. This is where it gets its “flesh-eating” name.

Thankfully, it’s treatable. A six to eight week course of specific antibiotics is an effective treatment, sometimes supported with surgery to remove the infected tissue.

Where can you catch it?

The World Health Organization considers Buruli ulcer a neglected tropical skin disease. Cases have been reported across 33 countries, primarily in west and central Africa.

However, since the early 2000s, Buruli ulcer has also been increasingly recorded in coastal Victoria, including suburbs around Melbourne and Geelong.

Scientists have long known Australian native possums were partly responsible for its spread, and suspected mosquitoes also played a role in the increase in cases. New research confirms this.

Our efforts to ‘beat Buruli’

Confirming the role of insects in outbreaks of an infectious disease is achieved by building up corroborating, independent evidence.

In this new research, published in Nature Microbiology, the team (including co-authors Tim Stinear, Stacey Lynch and Peter Mee) conducted extensive surveys across a 350 km² area of Victoria.

We collected mosquitoes and analysed the specimens to determine whether they were carrying the pathogen, and links to infected possums and people. It was like contact tracing for mosquitoes.

Aedes notoscriptus was the mosquito identified as carrying the bacteria that caused Buruli ulcer.

Cameron Webb (NSW Health Pathology)Molecular testing of the mosquito specimens showed that of the two most abundant mosquito species, only Aedes notoscriptus (a widespread species commonly known as the Australian backyard mosquito) was positive for Mycobacterium ulcerans.

We then used genomic tests to show the bacteria found on these mosquitoes matched the bacteria in possum poo and humans with Buruli ulcer.

We further analysed mosquito specimens that contained blood to show Aedes notoscriptus was feeding on both possums and humans.

To then link everything together, geospatial analysis revealed the areas where human Buruli ulcer cases occur overlap with areas where both mosquitoes and possums that harbour Mycobacterium ulcerans are active.

Stop its spread by stopping mozzies breeding

The mosquito in this study primarily responsible for the bacteria’s spread is Aedes notoscriptus, a mosquito that lays its eggs around water in containers in backyard habitats.

Controlling “backyard” mosquitoes is a critical part of reducing the risk of many global mosquito-borne disease, especially dengue and now Buruli ulcer.

You can reduce places where water collects after rainfall, such as potted plant saucers, blocked gutters and drains, unscreened rainwater tanks, and a wide range of plastic buckets and other containers. These should all be either emptied at least weekly or, better yet, thrown away or placed under cover.

Mosquitoes can lay eggs in a wide range of water-filled items in the backyard.

Cameron Webb (NSW Health Pathology)There is a role for insecticides too. While residual insecticides applied to surfaces around the house and garden will reduce mosquito populations, they can also impact other, beneficial, insects. Judicious use of such sprays is recommended. But there are ecological safe insecticides that can be applied to water-filled containers (such as ornamental ponds, fountains, stormwater pits and so on).

Recent research also indicates new mosquito-control approaches that use mosquitoes themselves to spread insecticides may soon be available.

How to protect yourself from bites

The first line of defence will remain personal protection measures against mosquito bites.

Covering up with loose fitted long sleeved shirts, long pants, and covered shoes will provide physical protection from mosquitoes.

Applying topical insect repellent to all exposed areas of skin has been proven to provide safe and effective protection from mosquito bites. Repellents should include diethytolumide (DEET), picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus.

While the rise in Buruli ulcer is a significant health concern, so too are many other mosquito-borne diseases. The steps to avoid mosquito bites and exposure to Mycobacteriam ulcerans will also protect against viruses such as Ross River, Barmah Forest, Japanese encephalitis, and Murray Valley encephalitis.

Cameron Webb, Clinical Associate Professor and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney; Peter Mee, Adjunct Associate Lecturer, School of Applied Systems Biology, La Trobe University; Stacey Lynch, Team Leader- Mammalian infection disease research, CSIRO, and Tim Stinear, Professor of Microbiology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Fast-Mimicking Diet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Live, Fast, Live Long

This is Dr. Valter Longo. He’s a biogerontologist and cell biologist, whose work has focused on fasting and nutrient response genes, and how we can leverage them against diseases and aging in general.

We reviewed his book recently:

What does he want us to know?

What to eat

Dr. Longo recommends a mostly plant-based diet (especially vegetables, whole grains, and legumes), but also having some fish. The bulk of our dietary fats, however, he says are best coming from olive oil and nuts.

He also advises aiming for nutritional density of vitamins and minerals in our diet, and/but supplementing with a multivitamin once every few days to cover any gaps.

If in doubt choosing between plant-based whole foods, he recommends that we choose those our ancestors will have eaten.

Read more: Longevity Diet For Adults

When to eat

Dr. Longo recommends time-restricted eating within a 12-hour window per day.

See also: Intermittent Fasting: We Sort The Science From The Hype

However, he also recommends (additionally or separately; it’s up to us; additionally is better but the point is it still has excellent benefits separately too) his “fast-mimicking diet” (FMD), which involves eating according to what we said in “What to eat”, but restricting it to 750 kcal per day, 5 days in a row, but not necessarily 5 days per week.

For example, the following was a 3-month study that involved doing this for only one 5-day cycle per month:

❝Three FMD cycles reduced body weight, trunk, and total body fat; lowered blood pressure; and decreased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). No serious adverse effects were reported.

A post hoc analysis of subjects from both FMD arms showed that body mass index, blood pressure, fasting glucose, IGF-1, triglycerides, total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and C-reactive protein were more beneficially affected in participants at risk for disease than in subjects who were not at risk.

Thus, cycles of a 5-day FMD are safe, feasible, and effective in reducing markers/risk factors for aging and age-related diseases.❞

~ Dr. Min Wei et al. ← Dr. Longo was

Note: the introduction mentions FMD in mice, but this is just referencing previous studies. This study is about FMD in humans!

Read in full: Fasting-mimicking diet and markers/risk factors for aging, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease

Want to know more?

You might like this (text-based) interview with Dr. Longo, with the Health Sciences Academy:

Eat, fast and live longer? Interview with Professor Valter Longo

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: