Nicotine Benefits (That We Don’t Recommend)!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Does nicotine have any benefits at all? I know it’s incredibly addictive but if you exclude the addiction, does it do anything?❞

Good news: yes, nicotine is a stimulant and can be considered a performance enhancer, for example:

❝Compared with the placebo group, the nicotine group exhibited enhanced motor reaction times, grooved pegboard test (GPT) results on cognitive function, and baseball-hitting performance, and small effect sizes were noted (d = 0.47, 0.46 and 0.41, respectively).❞

Read in full: Acute Effects of Nicotine on Physiological Responses and Sport Performance in Healthy Baseball Players

However, another study found that its use as a cognitive enhancer was only of benefit when there was already a cognitive impairment:

❝Studies of the effects of nicotinic systems and/or nicotinic receptor stimulation in pathological disease states such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and schizophrenia show the potential for therapeutic utility of nicotinic drugs.

In contrast to studies in pathological states, studies of nicotine in normal-non-smokers tend to show deleterious effects.

This contradiction can be resolved by consideration of cognitive and biological baseline dependency differences between study populations in terms of the relationship of optimal cognitive performance to nicotinic receptor activity.

Although normal individuals are unlikely to show cognitive benefits after nicotinic stimulation except under extreme task conditions, individuals with a variety of disease states can benefit from nicotinic drugs❞

Read in full: Effects of nicotinic stimulation on cognitive performance

Bad news: its addictive qualities wipe out those benefits due to tolerance and thus normalization in short order. So you may get those benefits briefly, but then you’re addicted and also lose the benefits, as well as also ruining your health—making it a lose/lose/lose situation quite quickly.

As an aside, while nicotine is poisonous per se, in the quantities taken by most users, the nicotine itself is not usually what kills. It’s mostly the other stuff that comes with it (smoking is by far and away the worst of all; vaping is relatively less bad, but that’s not a strong statement in this case) that causes problems.

See also: Vaping: A Lot Of Hot Air?

However, this is still not an argument for, say, getting nicotine gum and thinking “no harmful effects” because then you’ll be get a brief performance boost yes before it runs out and being addicted to it and now being in a position whereby if you stop, your performance will be lower than before you started (since you now got used to it, and it became your new normal), before eventually recovering:

In summary

We recommend against using nicotine in the first place, and for those who are addicted, we recommend quitting immediately if not contraindicated (check with your doctor if unsure; there are some situations where it is inadvisable to take away something your body is dependent on, until you correct some other thing first).

For more on quitting in general, see:

Addiction Myths That Are Hard To Quit

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

New Eye Drops vs Age-Related Macular Degeneration

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written previously on preventative interventions against age-related macular degeneration (AMD):

How To Avoid Age-Related Macular Degeneration

…and then supplemented that, to to speak, with:

Fatty Acids For The Eyes & Brain: The Good And The Bad

However, what if ADM happens anyway?

Not a dry eye in the house

Age-related macular degeneration comes in two forms, wet and dry, of which, dry is by far the most common (being 9 out of 10 of all cases of AMD).

It sounds like the sort of thing that eye drops should be in order for, but in fact, the wetness vs dryness is about what’s going on inside the macula, not what’s happening on the surface of the eye. Up until now, the only treatments available (aside from supplement regimes, which we linked just above) have been injectable drugs, which:

- are not fun (yes, the injection goes into the eyeball)

- don’t actually work very well (modest improvements in vision; significantly better than nothing though)

…and even those won’t help in the late stages.

However, a Korean research team has developed eye drops with peptides that inhibit the interactions between Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and TLR-signalling proteins, in a way that addresses part of the pathogenesis of AMD:

That’s quite a dense read though, so here’s a pop-science article that explains it more simply, but in more detail than we can here:

New eye drop treatment offers hope for dry AMD patients

This is a big improvement from the state of affairs previously, in which eye drops really couldn’t help at all:

What eye drops can treat macular degeneration? ← pop-science article from January 2023

No AMD, and/but want your eye health to be better?

Check out these:

10 Great Exercises to Improve Your Eyesight ← you can quickly see the results for yourself

Take care!

Share This Post

-

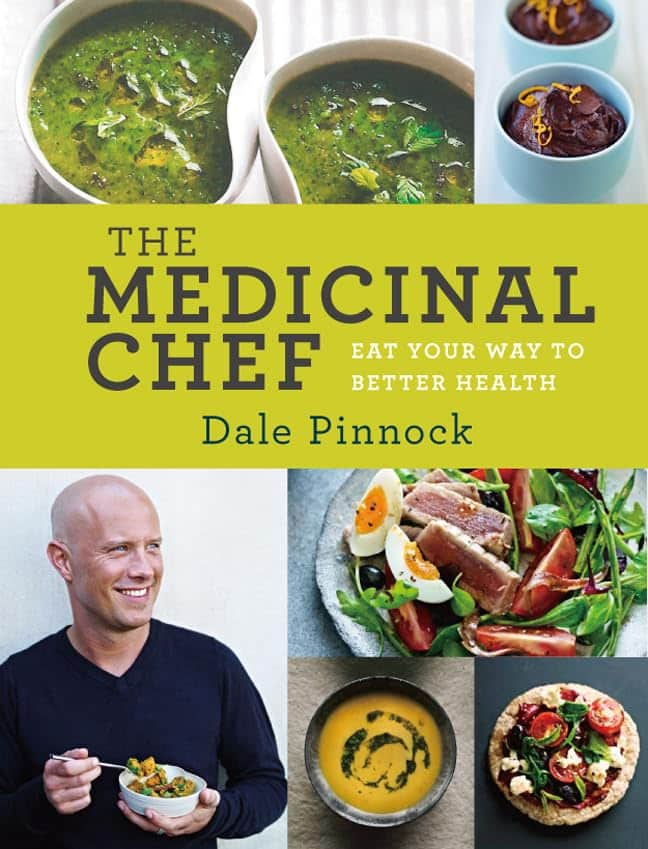

The Medicinal Chef – by Dale Pinnock

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The philosophy here is very much like our own—to borrow from Hippocrates: “let food be thy medicine”. Obviously please do also let medicine be thy medicine if you need it, but the point is that food is a very good starting place for combatting a lot of disease.

To this end, instead of labelling the recipes with such things as “V”, “Ve”, “GF” and suchlike, it assumes we can tell those things from the ingredients lists, and instead labels things per what they are especially good for:

- S: skin

- J: joints & bones

- R: respiratory system

- I: immune system

- M: metabolic health

- N: nervous system and mental health

- H: heart and circulation

- D: digestive system

- U: reproductive & urinary systems

As for the recipes themselves… They’re a lot like the recipes we share here at 10almonds in their healthiness, skill level, and balance of easy-to-find ingredients with the occasional “order it online” items that punch above their weight. In fact, we’ll probably modify some of the recipes for sharing here.

Bottom line: if you’re looking for genuinely healthy recipes that are neither too basic nor too arcane, this book has about 80 of them.

Click here to check out The Medicinal Chef: Healthy Every Day, and be healthy every day!

Share This Post

-

Heart Health vs Systemic Stress

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

At The Heart Of Good Health

This is Dr. Michelle Albert. She’s a cardiologist with a decades-long impressive career, recently including a term as the president of the American Heart Association. She’s the current Admissions Dean at UCSF Medical School. She’s accumulated enough awards and honors that if we list them, this email will not fit in your inbox without getting clipped.

What does she want us to know?

First, lifestyle

Although Dr. Albert is also known for her work with statins (which found that pravastatin may have anti-inflammatory effects in addition to lipid-lowering effects, which is especially good news for women, for whom the lipid-lowering effects may be less useful than for men), she is keen to emphasize that they should not be anyone’s first port-of-call unless “first” here means “didn’t see the risk until it was too late and now LDL levels are already ≥190 mg/dL”.

Instead, she recommends taking seriously the guidelines on:

- getting plenty of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein

- avoiding red meat, processed meats, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages

- getting your 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise

- avoiding alcohol, and definitely abstaining from smoking

See also: These Top Five Things Make The Biggest Difference To Health

Next, get your house in order

No, not your home gym—though sure, that too!

But rather: after the “Top Five Things” we linked just above, the sixth on the list would be “reduce stress”. Indeed, as Dr. Albert says:

❝Heart health is not just about the physical heart but also about emotional well-being. Stress management is crucial for a healthy heart❞

~ Dr. Michelle Albert

This is where a lot of people would advise mindfulness meditation, CBT, somatic therapies, and the like. And these things are useful! See for example:

No-Frills, Evidence-Based Mindfulness

…and:

However, Dr. Albert also advocates for awareness of what some professionals have called “Shit Life Syndrome”.

This is more about socioeconomic factors. There are many of those that can’t be controlled by the individual, for example:

❝Adverse maternal experiences such as depression, economic issues and low social status can lead to poor cognitive outcomes as well as cardiovascular disease.

Many jarring statistics illuminate a marked wealth gap by race and ethnicity… You might be thinking education could help bridge that gap. But it is not that simple.

While education does increase wealth, the returns are not the same for everyone. Black persons need a post-graduate degree just to attain similar wealth as white individuals with a high school degree.❞

~ Dr. Michelle Albert

Read in full: AHA president: The connection between economic adversity and cardiovascular health

What this means in practical terms (besides advocating for structural change to tackle the things such as the racism that has been baked into a lot of systems for generations) is:

Be aware not just of your obvious health risk factors, but also your socioeconomic risk factors, if you want to have good general health outcomes.

So for example, let’s say that you, dear reader, are wealthy and white, in which case you have some very big things in your favor, but are you also a woman? Because if so…

Women and Minorities Bear the Brunt of Medical Misdiagnosis

See also, relevant for some: Obesity Discrimination In Healthcare Settings ← you’ll need to scroll to the penultimate section for this one.

In other words… If you are one of the majority of people who is a woman and/or some kind of minority, things are already stacked against you, and not only will this have its own direct harmful effect, but also, it’s going to make your life harder and that stress increases CVD risk more than salt.

In short…

This means: tackle not just your stress, but also the things that cause that. Look after your finances, gather social support, know your rights and be prepared to self-advocate / have someone advocate for you, and go into medical appointments with calm well-prepared confidence.

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

When should you get the updated COVID-19 vaccine?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Updated COVID-19 vaccines are now available: They’re meant to give you the best protection against the strain of the virus that is making people severely sick and also causing deaths.

Many people were infected during the persistent summer wave, which may leave you wondering when you should get the updated vaccine. The short answer is that it depends on when you last got infected or vaccinated and on your particular level of risk.

We heard from six experts—including medical doctors and epidemiologists—about when they recommend getting an updated vaccine. Read on to learn what they said. And to make it easy, check out the flowchart below.

A flowchart to help you decide when is the best time to get the 2024-2025 updated COVID-19 vaccine. If I was infected with COVID-19 this summer, when should I get the updated vaccine?

All the experts we spoke to agreed that if you were infected this summer, you should wait at least three months since you were infected to get vaccinated.

“Generally, an infection may be protective for about three months,” Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, tells PGN. “If they got infected three or more months ago, it is a good idea to get vaccinated sooner than later.”

This three-month rule applies if you got vaccinated over the summer, which may be the case for some immunocompromised people, adds Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

If I didn’t get infected with COVID-19 this summer, when should I get vaccinated?

Most of the experts we talked to say that if you didn’t get infected with COVID-19 this summer, you should get the vaccine as soon as possible. Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, emphasizes that if this applies to you, you should get vaccinated as soon as possible, especially given the current COVID-19 surge.

Al-Aly agrees. “Vaccine-derived immunity lasts for several months, and it should cover the winter season. Plus, the current vaccine is a KP.2-adapted vaccine, so it will work most optimally against KP.2 and related subvariants [such as] KP.3 that are circulating now,” Al-Aly says. “We don’t know when the virus will mutate to a variant that is not compatible with the KP.2 vaccine.”

Al-Aly adds that if you’d rather take the protection you can get right now, “It may make more sense to get vaccinated sooner than later.”

This especially applies if you’re over 65 or immunocompromised and you haven’t received a COVID-19 vaccine in a year or more because, as Chin-Hong adds, “that is the group that is being hospitalized and disproportionately dying now.”

Some experts—including epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina, author of newsletter Your Local Epidemiologist—also say that if you’re younger than 65 and not immunocompromised, you can consider waiting and aiming to get vaccinated before Halloween to get the best protection in the winter, when we’re likely to experience another wave because of the colder weather, gathering indoors, and the holidays.

“I am more worried about the winter than the summer, so I would think of October (some time before Halloween) as the ‘Goldilocks moment’—not too early, not too late, but just right,” Chin-Hong adds. Time it “such that your antibodies peak during the winter when COVID-19 cases are expected to exceed what we are seeing this summer.”

My children are starting school—should I get them vaccinated now?

According to most experts we spoke to, now is a good time to get your children vaccinated.

Jennifer Nuzzo, professor of epidemiology and director of the Pandemic Center at the Brown University School of Public Health, adds that “with COVID-19 infection levels as high as they are and increased exposures in school,” now is a particularly good time to get an updated vaccine if people haven’t gotten COVID-19 recently.

Additionally, respiratory viruses spike when kids are back in school, so “doing everything you can to reduce your child’s risk of infection can help protect families and communities,” says epidemiologist Jessica Malaty Rivera, science communications advisor at the de Beaumont Foundation.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

(Disclosure: The de Beaumont Foundation is a partner of The Public Good Projects, the organization that owns Public Good News.)

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Bored of Lunch – by Nathan Anthony

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cooking with a slow cooker is famously easy, but often we settle down on a few recipes and then don’t vary. This book brings a healthy dose of inspiration and variety.

The recipes themselves range from comfort food to fancy entertaining, pasta dishes to risottos, and even what the author categorizes as “fakeaways” (a play on the British English “takeaway”, cf. AmE “takeout”), so indulgent nights in have never been healthier!

For each recipe, you’ll see a nice simple clear layout of all you’d expect (ingredients, method, etc) plus calorie count, so that you can have a rough idea of how much food each meal is.

In terms of dietary restrictions you may have, there’s quite a variety here so it’ll be easy to find things for all needs, and in addition to that, optional substitutions are mostly quite straightforward too.

Bottom line: if you have a slow cooker but have been cooking only the same three things in it for the past ten years, this is the book to liven things up, while staying healthy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Come As You Are – by Dr. Emily Nagoski

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve all heard the jokes, things like: Q: “Why is the clitoris like Antarctica?” A: “Most men know it’s there; most don’t give a damn”

But… How much do people, in general, really know about the anatomy and physiology of sexual function? Usually very little, but often without knowing how little we know.

This book looks to change that. Geared to a female audience, but almost everyone will gain useful knowledge from this.

The writing style is very easy-to-read, and there are “tl;dr” summaries for those who prefer to skim for relevant information in this rather sizeable (400 pages) tome.

Yes, that’s “what most people don’t know”. Four. Hundred. Pages.

We recommend reading it. You can thank us later!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: