‘Naked carbs’ and ‘net carbs’ – what are they and should you count them?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

According to social media, carbs come in various guises: naked carbs, net carbs, complex carbs and more.

You might be wondering what these terms mean or if all carbs are really the same. If you are into “carb counting” or “cutting carbs”, it’s important to make informed decisions about what you eat.

What are carbs?

Carbohydrates, or “carbs” for short, are one of the main sources of energy we need for brain function, muscle movement, digestion and pretty much everything our bodies do.

There are two classifications of carbs, simple and complex. Simple carbs have one or two sugar molecules, while complex carbs are three or more sugar molecules joined together. For example, table sugar is a simple carb, but starch in potatoes is a complex carb.

All carbs need to be broken down into individual molecules by our digestive enzymes to be absorbed. Digestion of complex carbs is a much slower process than simple carbs, leading to a more gradual blood sugar increase.

Fibre is also considered a complex carb, but it has a structure our body is not capable of digesting. This means we don’t absorb it, but it helps with the movement of our stool and prevents constipation. Our good gut bacteria also love fibre as they can digest it and use it for energy – important for a healthy gut.

What about ‘naked carbs’?

“Naked carbs” is a popular term usually used to refer to foods that are mostly simple carbs, without fibre or accompanying protein or fat. White bread, sugary drinks, jams, sweets, white rice, white flour, crackers and fruit juice are examples of these foods. Ultra-processed foods, where the grains are stripped of their outer layers (including fibre and most nutrients) leaving “refined carbs”, also fall into this category.

One of the problems with naked carbs or refined carbs is they digest and absorb quickly, causing an immediate rise in blood sugar. This is followed by a rapid spike in insulin (a hormone that signals cells to remove sugar from blood) and then a drop in blood sugar. This can lead to hunger and cravings – a vicious cycle that only gets worse with eating more of the same foods.

Pexels/Alexander Grey

What about ‘net carbs’?

This is another popular term tossed around in dieting discussions. Net carbs refer to the part of the carb food that we actually absorb.

Again, fibre is not easily digestible. And some carb-rich foods contain sugar alcohols, such as sweeteners (like xylitol and sorbitol) that have limited absorption and little to no effect on blood sugar. Deducting the value of fibre and sugar alcohols from the total carbohydrate content of a food gives what’s considered its net carb value.

For example, canned pear in juice has around 12.3g of “total carbohydrates” per 100g, including 1.7g carb + 1.7g fibre + 1.9g sugar alcohol. So its net carb is 12.3g – 1.7g – 1.9g = 8.7g. This means 8.7g of the 12.3g total carbs impacts blood sugar.

The nutrition labels on packaged foods in Australia and New Zealand usually list fibre separately to carbohydrates, so the net carbs have already been calculated. This is not the case in other countries, where “total carbohydrates” are listed.

Does it matter though?

Whether or not you should care about net or naked carbs depends on your dietary preferences, health goals, food accessibility and overall nutritional needs. Generally speaking, we should try to limit our consumption of simple and refined carbs.

The latest World Health Organization guidelines recommend our carbohydrate intake should ideally come primarily from whole grains, vegetables, fruits and pulses, which are rich in complex carbs and fibre. This can have significant health benefits (to regulate hunger, improve cholesterol or help with weight management) and reduce the risk of conditions such as heart disease, obesity and colon cancer.

In moderation, naked carbs aren’t necessarily bad. But pairing them with fats, protein or fibre can slow down the digestion and absorption of sugar. This can help to stabilise blood sugar levels, prevent spikes and crashes and support personal weight management goals. If you’re managing diabetes or insulin resistance, paying attention to the composition of your meals, and the quality of your carbohydrate sources is essential.

A ketogenic (high fat, low carb) diet typically restricts carb intake to between 20 and 50g each day. But this carb amount refers to net carbs – so it is possible to eat more carbs from high-fibre sources.

Shutterstock

Some tips to try

Some simple strategies can help you get the most out of your carb intake:

reduce your intake of naked carbs and foods high in sugar and white flour, such as white bread, table sugar, honey, lollies, maple syrup, jam, and fruit juice

opt for protein- and fibre-rich carbs. These include oats, sweet potatoes, nuts, avocados, beans, whole grains and broccoli

if you are eating naked carbs, dress them up with some protein, fat and fibre. For example, top white bread with a nut butter rather than jam

if you are trying to reduce the carb content in your diet, be wary of any symptoms of low blood glucose, including headaches, nausea, and dizziness

- working with a health-care professional such as an accredited practising dietitian or your GP can help develop an individualised diet plan that meets your specific needs and goals.

Correction: this article has been updated to indicate how carbohydrates are listed on food nutrition labels in Australia and New Zealand.

Saman Khalesi, Senior Lecturer and Discipline Lead in Nutrition, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity Australia; Anna Balzer, Lecturer, Medical Science School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, CQUniversity Australia; Charlotte Gupta, Postdoctoral research fellow, CQUniversity Australia; Chris Irwin, Senior Lecturer in Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Health Sciences & Social Work, Griffith University, and Grace Vincent, Senior Lecturer, Appleton Institute, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What’s the difference between vegan and vegetarian?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

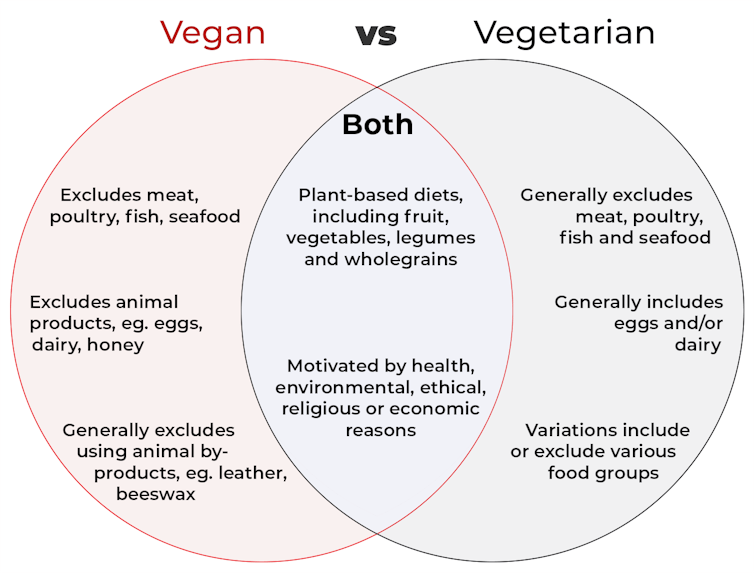

Vegan and vegetarian diets are plant-based diets. Both include plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains.

But there are important differences, and knowing what you can and can’t eat when it comes to a vegan and vegetarian diet can be confusing.

So, what’s the main difference?

Creative Cat Studio/Shutterstock What’s a vegan diet?

A vegan diet is an entirely plant-based diet. It doesn’t include any meat and animal products. So, no meat, poultry, fish, seafood, eggs, dairy or honey.

What’s a vegetarian diet?

A vegetarian diet is a plant-based diet that generally excludes meat, poultry, fish and seafood, but can include animal products. So, unlike a vegan diet, a vegetarian diet can include eggs, dairy and honey.

But you may be wondering why you’ve heard of vegetarians who eat fish, vegetarians who don’t eat eggs, vegetarians who don’t eat dairy, and even vegetarians who eat some meat. Well, it’s because there are variations on a vegetarian diet:

- a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet excludes meat, poultry, fish and seafood, but includes eggs, dairy and honey

- an ovo-vegetarian diet excludes meat, poultry, fish, seafood and dairy, but includes eggs and honey

- a lacto-vegetarian diet excludes meat, poultry, fish, seafood and eggs, but includes dairy and honey

- a pescatarian diet excludes meat and poultry, but includes eggs, dairy, honey, fish and seafood

- a flexitarian, or semi-vegetarian diet, includes eggs, dairy and honey and may include small amounts of meat, poultry, fish and seafood.

Are these diets healthy?

A 2023 review looked at the health effects of vegetarian and vegan diets from two types of study.

Observational studies followed people over the years to see how their diets were linked to their health. In these studies, eating a vegetarian diet was associated with a lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (such as heart disease or a stroke), diabetes, hypertension (high blood pressure), dementia and cancer.

For example, in a study of 44,561 participants, the risk of heart disease was 32% lower in vegetarians than non-vegetarians after an average follow-up of nearly 12 years.

Further evidence came from randomised controlled trials. These instruct study participants to eat a specific diet for a specific period of time and monitor their health throughout. These studies showed eating a vegetarian or vegan diet led to reductions in weight, blood pressure, and levels of unhealthy cholesterol.

For example, one analysis combined data from seven randomised controlled trials. This so-called meta-analysis included data from 311 participants. It showed eating a vegetarian diet was associated with a systolic blood pressure (the first number in your blood pressure reading) an average 5 mmHg lower compared with non-vegetarian diets.

It seems vegetarian diets are more likely to be healthier, across a number of measures.

For example, a 2022 meta-analysis combined the results of several observational studies. It concluded a vegetarian diet, rather than vegan diet, was recommended to prevent heart disease.

There is also evidence vegans are more likely to have bone fractures than vegetarians. This could be partly due to a lower body-mass index and a lower intake of nutrients such as calcium, vitamin D and protein.

But it can be about more than just food

Many vegans, where possible, do not use products that directly or indirectly involve using animals.

So vegans would not wear leather, wool or silk clothing, for example. And they would not use soaps or candles made from beeswax, or use products tested on animals.

The motivation for following a vegan or vegetarian diet can vary from person to person. Common motivations include health, environmental, ethical, religious or economic reasons.

And for many people who follow a vegan or vegetarian diet, this forms a central part of their identity.

More than a diet: veganism can form part of someone’s identity. Shutterstock So, should I adopt a vegan or vegetarian diet?

If you are thinking about a vegan or vegetarian diet, here are some things to consider:

- eating more plant foods does not automatically mean you are eating a healthier diet. Hot chips, biscuits and soft drinks can all be vegan or vegetarian foods. And many plant-based alternatives, such as plant-based sausages, can be high in added salt

- meeting the nutrient intake targets for vitamin B12, iron, calcium, and iodine requires more careful planning while on a vegan or vegetarian diet. This is because meat, seafood and animal products are good sources of these vitamins and minerals

- eating a plant-based diet doesn’t necessarily mean excluding all meat and animal products. A healthy flexitarian diet prioritises eating more whole plant-foods, such as vegetables and beans, and less processed meat, such as bacon and sausages

- the Australian Dietary Guidelines recommend eating a wide variety of foods from the five food groups (fruit, vegetables, cereals, lean meat and/or their alternatives and reduced-fat dairy products and/or their alternatives). So if you are eating animal products, choose lean, reduced-fat meats and dairy products and limit processed meats.

Katherine Livingstone, NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellow and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Celery vs Radish – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

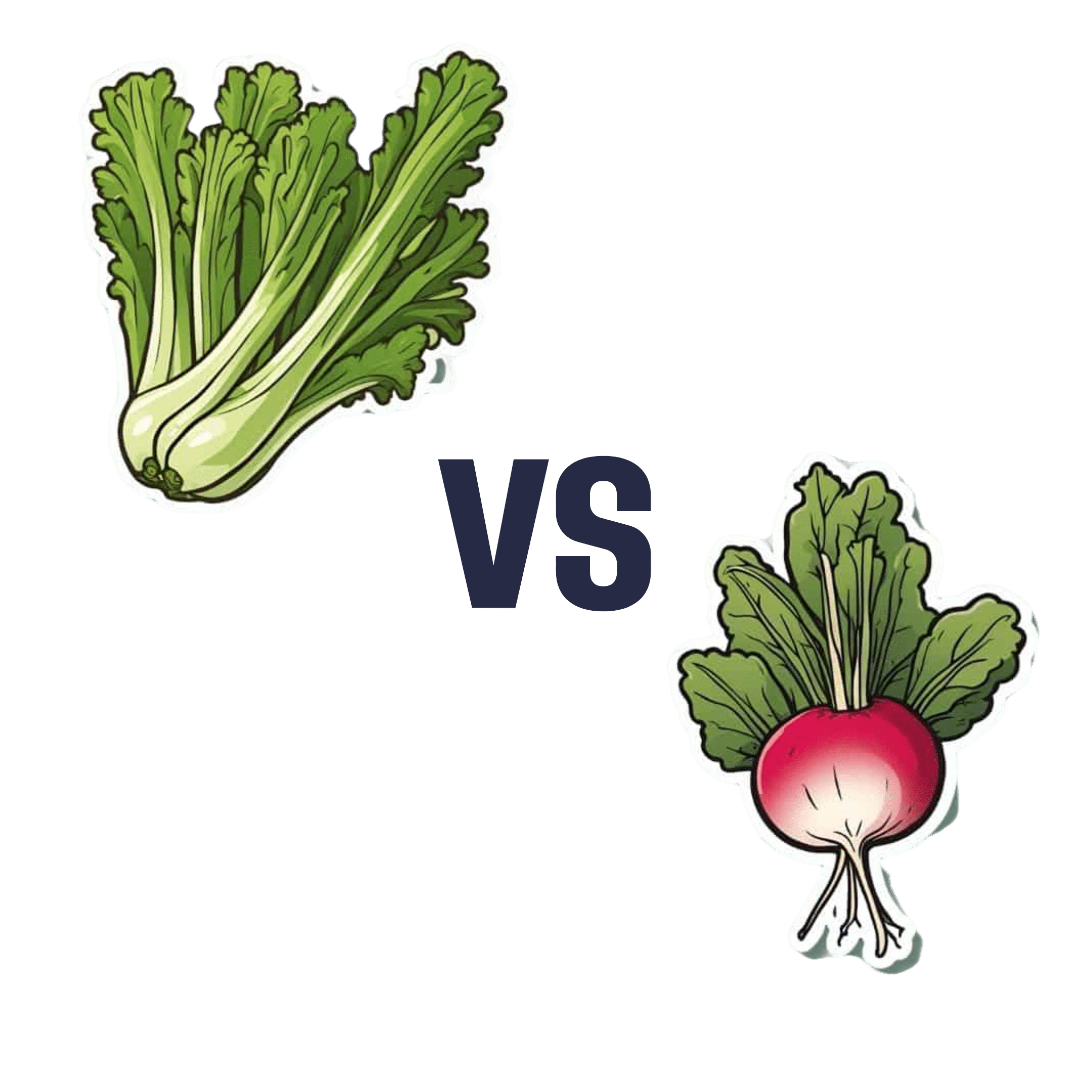

When comparing celery to radish, we picked the celery.

Why?

It was very close! And yes, surprising, we know. Generally speaking, the more colorful/pigmented an edible plant is, the healthier it is. Celery is just one of those weird exceptions (as is cauliflower, by the way).

Macros-wise, these two are pretty much the same—95% water, with just enough other stuff to hold them together. The proportions of “other stuff” are also pretty much equal.

In the category of vitamins, celery has more vitamin K while radish has more vitamin C; the other vitamins are pretty close to equal. We’ll call this one a minor win for celery, as vitamin K is found in fewer foods than vitamin C.

When it comes to minerals, celery has more calcium, manganese, phosphorus, and potassium, while radish has more copper, iron, selenium, and zinc. We’ll call this a minor win for radish, as the margins are a little wider for its minerals.

So, that makes the score 1–1 so far.

Both plants have an assortment of polyphenols, of which, when we add up the averages, celery comes out on top by some way. Celery also comes out on top when we do a head-to-head of the top flavonoid of each; celery has 5.15mg/100g of apigenin to radish’s 0.63mg/100g kaempferol.

Which means, both are great healthy foods, but celery wins the day.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Celery vs Cucumber – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Galveston Diet – by Dr. Mary Claire Haver

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed “It’s Not You, It’s Your Hormones” by nutritionist Nikki Williams, and noted at the time that it was very similar to the bestselling “The Galveston Diet”, not just in its content but all the way down its formatting. Some Amazon reviewers have even gone so far as to suggest that “It’s Not You, It’s Your Hormones” (2017) brazenly plagiarized “The Galveston Diet” (2023). However, after carefully examining the publication dates, we feel quite confident that the the earlier book did not plagiarize the later one.

Of course, we would not go so far as to make a counter-accusation of plagiarism the other way around; it was surely just a case of Dr. Haver having the same good ideas 6 years later.

Still, while the original book by Nikki Williams did not get too much international acclaim, the later one by Dr. Mary Claire Haver has had very good marketing and thus received a lot more attention, so let’s review it:

Dr. Haver’s basic principle is (again) that we can manage our hormonal fluctuations, by managing our diet. Specifically, in the same three main ways:

- Intermittent fasting

- Anti-inflammatory diet

- Eating more protein and healthy fats

Why should these things matter to our hormones? The answer is to remember that our hormones aren’t just the sex hormones. We have hormones for hunger and satedness, hormones for stress and relaxation, hormones for blood sugar regulation, hormones for sleep and wakefulness, and more. These many hormones make up our endocrine system, and affecting one part of it will affect the others.

Will these things magically undo the effects of the menopause? Well, some things yes, other things no. No diet can do the job of HRT. But by tweaking endocrine system inputs, we can tweak endocrine system outputs, and that’s what this book is for.

The style is once again very accessible and just as clear, and Dr. Haver also walks us just as skilfully through the changes we may want to make, to avoid the changes we don’t want. The recipes are also very similar, so if you loved the recipes in the other book, you certainly won’t dislike this book’s menu.

In the category of criticism, there is (as with the other book by the other author) some extra support that’s paywalled, in the sense that she wants the reader to buy her personally-branded online plan, and it can feel a bit like she’s holding back in order to upsell to that.

Bottom line: this book is (again) aimed at peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women. It could also (again) definitely help a lot of people with PCOS too, and, when it comes down to it, pretty much anyone with an endocrine system. It’s (still) a well-evidenced, well-established, healthy way of eating regardless of age, sex, or (most) physical conditions.

Click here to check out The Galveston Diet, and enjoy its well-told, well-formatted advice!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What’s So Special About Alpha-Lipoic Acid?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Access-All-Areas Antioxidant

Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) is one of the most bioavailable antioxidants in existence. A bold claim, but most antioxidants are only water-soluble or fat-soluble, whereas ALA is both. This has far-reaching implications—and we mean that literally, because its “go everywhere” status means that it can access (and operate in) all living cells of the human body.

We make it inside our body, and we can also get it in our diet, or take it as a supplement.

What foods contain it?

The richest food sources are:

- For the meat-eaters: organ meats

- For everyone: broccoli, tomatoes, & spinach

However, supplements are more efficient at delivering it, by several orders of magnitude:

Read more: Lipoic acid – biological activity and therapeutic potential

What are its benefits?

Most of its benefits are the usual benefits you would expect from any antioxidant, just, more of it. In particular, reduced inflammation and slowed skin aging are common reasons that people take ALA as a supplement.

Does it really reduce inflammation?

Yes, it does. This one’s not at all controversial, as this systematic review of studies shows:

(C-reactive protein is a marker of inflammation)

Does it really reduce skin aging?

Again yes—which again is not surprising for such a potent antioxidant; remember that oxidative stress is one of the main agonists of cellular aging:

As a special feature, ALA shows particular strength against sun-related skin aging, because of how it protects against UV radiation and increases levels of gluthianone, which also helps:

- Photochemical stability of lipoic acid and its impact on skin ageing

- Modern approach to topical treatment of aging skin

Where can I get some?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Make Your Vegetables Work Better Nutritionally

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most people know that boiling vegetables to death is generally not best for them, but raw isn’t always best either, and if we want to not sabotage our food, then there’s more to bear in mind than “just steam them, then”.

So, what should we keep in mind?

Water solubility

Many nutrients are water-soluble, including vitamin C, vitamin B-complex (as in, the collection of B-vitamins), and flavonoids, as well as many other polyphenols.

This means that if you cook your vegetables (which includes beans, lentils, etc) in water, a lot of the nutrients will go into the water, and be lost if you then drain that.

There are, thus, options;

- Steaming, yes

- Use just enough water to slow-cook or pressure-cook things that are suitable for slow-cooking, or pressure-cooking such as those beans and lentils. That way, when it’s done, there’s no excess water to drain, and all the nutrients are still in situ.

- Use as much water as you like, but then keep the excess water to make a soup, sauce, or broth.

- Use a cooking method other than water, where appropriate. For example, roasting peppers is a much better idea than roasting dried pulses.

- Consume raw, where appropriate.

Fat solubility

Many nutrients are fat-soluble, including vitamins A, D, E, and K, as well as a lot of carotenoids (including heavy-hitters lycopene and β-carotene) and many other polyphenols.

We’re now going to offer almost the opposite advice to that we had about water solubility. This is because unless they are dried, vegetables already contain water, whereas many contain only trace amounts of fat. Consequently, the advice this time is to add fat.

There are options:

- Cook with a modest amount of your favorite healthy cooking oil (our general go-to is extra-virgin olive oil, but avocado oil is great especially for higher temperature cooking, and an argument can be made for coconut oil sometimes)

- Remember that this goes for roasting, too. Brush those vegetables with a touch of olive oil, and not only will they be delicious, they’ll be more nutritious, too.

- Drizzle some the the above, if you’re serving things raw and it’s appropriate. This goes also for things like salads, so dress them!

- Enjoy your vegetables alongside healthy fatty foods such as nuts and seeds (or fatty animal products, if you eat those; fatty fish is a fine option here, in moderation, as are eggs, or fermented dairy products).

For a deeper understanding: Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy?

Do not, however, deep-fry your foods unless it’s really necessary and then only for an occasional indulgence that you simply accept will be unhealthy. Not only is deep-frying terrible for the health in a host of ways (ranging from an excess of oil in the resultant food, to acrylamide, to creating Advanced Glycation End-products*), but also those fat-soluble nutrients? Guess where they’ll go. And unlike with the excess vegetable-cooking water that you can turn into soup or whatever, we obviously can’t recommend doing that with deep-fryer oil.

*see also: Are You Eating AGEs?

Temperature sensitivity

Many nutrients are sensitive to temperature, including vitamin C (breaks down when exposed to high temperatures) and carotenoids (are released when exposed to higher temperatures). Another special case is ergothioneine, “the longevity vitamin” that’s not a vitamin, found in mushrooms, which is also much more bioavailable when cooked.

So, if you’re eating something for vitamin C, then raw is best if that’s a reasonable option.

And if it’s not a reasonable option? Well, then you can either a) just cope with the fact it’s going to have less vitamin C in it, or b) cook it as gently and briefly as reasonably possible.

On the other hand, if you’re eating something for carotenoids (especially including lycopene and β-carotene), or ergothioneine, then cooked is best.

Additionally, if your food is high in oxalates (such as spinach), and you don’t want it to be (for example because you have kidney problems, which oxalates can exacerbate, or would like to get more calcium out of the spinach and into your body, which which oxalic acid would inhibit), then cooked is best, as it breaks down the oxalates.

Same goes for phytates, another “anti-nutrient” found in some whole grains (such as rice and wheat); cooking breaks it down, therefore cooked is best.

This latter is not, however, applicable in the case of brown rice protein powder, for those who enjoy that—because phytates aren’t found in the part of the rice that’s extracted to make that.

And as for brown rice itself? Does contain phytates… Which can be reduced by soaking and heating, preferably both, to the point that the nutritional value is better than it would have been had there not been phytic acid present in the first place; in other words: cooked is best.

You may be wondering: “who is eating rice raw?” and the answer is: people using rice flour.

See: Brown Rice Protein: Strengths & Weaknesses

Want to know more?

Here’s a great rundown from Dr. Rosalind Gibson, Dr. Leah Perlas, and Dr. Christine Hotz:

Improving the bioavailability of nutrients in plant foods at the household level

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Dopamine Precursor And More

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Is This Supplement “NALT”?

N-Acetyl L-Tyrosine (NALT) is a form of tyrosine, an amino acid that the body uses to build other things. What other things, you ask?

Well, like most amino acids, it can be used to make proteins. But most importantly and excitingly, the body uses it to make a collection of neurotransmitters—including dopamine and norepinephrine!

- Dopamine you’ll probably remember as “the reward chemical” or perhaps “the motivation molecule”

- Norepinephrine, also called noradrenaline, is what powers us up when we need a burst of energy.

Both of these things tend to get depleted under stressful conditions, and sometimes the body can need a bit of help replenishing them.

What does the science say?

This is Research Review Monday, after all, so let’s review some research! We’re going to dive into what we think is a very illustrative study:

A 2015 team of researchers wanted to know whether tyrosine (in the form of NALT) could be used as a cognitive enhancer to give a boost in adverse situations (times of stress, for example).

They noted:

❝The potential of using tyrosine supplementation to treat clinical disorders seems limited and its benefits are likely determined by the presence and extent of impaired neurotransmitter function and synthesis.❞

More on this later, but first, the positive that they also found:

❝In contrast, tyrosine does seem to effectively enhance cognitive performance, particularly in short-term stressful and/or cognitively demanding situations. We conclude that tyrosine is an effective enhancer of cognition, but only when neurotransmitter function is intact and dopamine and/or norepinephrine is temporarily depleted❞

That “but only”, is actually good too, by the way!

You do not want too much dopamine (that could cause addiction and/or psychosis) or too much norepinephrine (that could cause hypertension and/or heart attacks). You want just the right amount!

So it’s good that NALT says “hey, if you need some more, it’s here, if not, no worries, I’m not going to overload you with this”.

Read the study: Effect of tyrosine supplementation on clinical and healthy populations under stress or cognitive demands

About that limitation…

Remember they said that it seemed unlikely to help in treating clinical disorders with impaired neurotransmitter function and/or synthesis?

Imagine that you employ a chef in a restaurant, and they can’t keep up with the demand, and consequently some of the diners aren’t getting fed. Can you fix this by supplying the chef with more ingredients?

Well, yes, if and only if the problem is “the chef wasn’t given enough ingredients”. If the problem is that the oven (or the chef’s wrist) is broken, more ingredients aren’t going to help at all—something different is needed in those cases.

So it is with, for example, many cases of depression.

See for example: Tyrosine for depression: a double-blind trial

About blood pressure…

You may be wondering, “if NALT is a precursor of norepinephrine, a vasoconstrictor, will this increase my blood pressure adversely?”

Well, check with your doctor as your own situation may vary, but under normal circumstances, no. The effect of NALT is adaptogenic, meaning that it can help keep its relevant neurotransmitters at healthy levels—not too low or high.

See what we mean, for example in this study where it actually helped keep blood pressure down while improving cognitive performance under stress:

Effect of tyrosine on cognitive function and blood pressure under stress

Bottom line:

For most people, NALT is a safe and helpful way to help keep healthy levels of dopamine and norepinephrine during times of stress, giving cognitive benefits along the way.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: