Increase Your Muscle Mass Boost By 26% (No Extra Effort, No Supplements)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You’ve probably seen this technology advertised, but the trick is in how it’s used (which is not how most people use it).

It’s about neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), also called electrical muscle stimulation (EMS); in other words, those squid-like electrode kits that promise “six-pack abs without exercise”, by stimulating the muscles for you—using the exact same tech as for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), for pain relief.

Do they work for pain relief? Yes, for many people in any case. But that’s beyond the scope of today’s article.

Do they work for building muscles as advertised? No. The limiting factor is that they can’t fully exert the muscles in the same way actual exercise can, because of the limitations to how much electrical current can safely be applied.

However…

The cyborgization of your regular workout

A meta-analysis of 13 studies compared two [meta-]groups of exercisers:

- Group 1 doing conventional resistance training

- Group 2 doing the same resistance training, plus NMES at the same time (specifically: NMES of the same muscles being used in the workout)

The analysis had two output variables: strength and muscle mass

What they found: group 2 enjoyed more than 31% greater strength gains, and 26% greater muscle mass gains, from the same training over the same period of time.

Of course, one of the biggest challenges to strength gain and muscle mass gain is hitting a plateau, so it’s worth noting that when they looked at training periods ranging from 2 weeks to 16 weeks, longer durations yielded better results—it is, it seems, the gift that keeps on giving.

You can find the paper here (which also explains how they analysed data from 13 different studies to get one coherent set of results):

How it works and why it matters

While the paper itself does not go into how it works, a reasonable hypothesis is that it works by “confusing” the muscles—because they are receiving mixed signals (one set from your brain, one set from the electrodes), with fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers both working at the same time.

Another way to “confuse” the muscles is by High Intensity [Interval] Resistance Training (HIRT)—which is basically High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), but for resistance training specifically.

See: How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body) and HIIT, But Make It HIRT

Now, we want to confuse our muscles, not our readers, so if that’s all too much to juggle at once, just pick one and go with it. But today’s article is about the RT+NEMS combination, so perhaps you’ll pick that.

Why it matters: as we get older, sarcopenia (the loss of muscle mass) becomes more of an issue, and even if we’re not inclined to a career in bodybuilding, we do still need to at least maintain a healthy muscle mass because:

- Strong muscles improve our stability and make us less likely to fall

- Strong muscles force the body to build strong bones to hold them on, which means lower risk of fractures or worse

- Muscle mass itself improves the body’s basal metabolic rate, which means systemic benefits to the whole body (including against metabolic diseases especially)

See also: Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Want to try it?

If you don’t already have a NMES/EMS/TENS kit lying around the house, here’s an example product on Amazon—remember to use it simultaneously with your regular resistance training workout, on the same muscles at the same time, to get the benefit we talked about! 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Foods Linked To Urinary Incontinence In Middle-Age (& Foods That Avert It)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Incontinence is an inconvenience associated with aging, especially for women. Indeed, as the study we’re going to talk about today noted:

❝Estrogen deficiency during menopause, aging, reproductive history, and factors increasing intra-abdominal pressure may lead to structural and functional failure in the pelvic floor.❞

However, that was just the “background”, before they got the study going, because…

❝Lifestyle choices, such as eating behavior, may contribute to pelvic floor disorders. The objective of the study was to investigate associations of eating behavior with symptoms of pelvic floor disorders, that is, stress urinary incontinence, urgency urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and constipation or defecation difficulties among middle-aged women.❞

~ Ibid.

How the study went

The researchers examined 1,098 Finnish women aged 47–55. It was a cross-sectional observational study, so no intervention was made, just: gathering data and analysing it. They examined:

- Eating behavior (i.e. what one’s diet is like; their questionnaire was quite comprehensive and the simplified conclusion doesn’t do that justice)

- Food consumption frequency (i.e. temporal patterns of eating)

- Demographic variables (e.g. age, education, etc)

- Gynecological variables (e.g. menopause status, hysterectomy, etc)

- Physical activity variables (e.g. light, moderate, heavy, previous history of no exercise, regular, competitive sport, etc)

With those things taken into account, the researchers crunched the numbers to assess the associations of dietary factors with pelvic floor disorders.

What they found

Adjusting for possible confounding variables…

- those with disordered eating patterns (e.g. overeating, restrictive eating, swinging between the two behaviors) were 50% higher chance of developing urinary incontinence than the norm

- those who more frequently consumed ready-made foods got 50% higher chance of developing urinary incontinence than the norm

- those who ate fruits daily enjoyed a 20% lower chance of urinary incontinence than the norm

So, in practical terms:

- practice mindful eating

- avoid ready-made foods

- enjoy fruit

You can read the paper in full here (it obviously goes into a lot more detail, and also covers other things beyond the scope of this article, such as fecal incontinence or, conversely, constipation—needless to say, the same advice stands in any case):

As for why this works the way it does: the study focused on the association and only hypothesized the question of “how”, but they did write a bit about that too, and it is almost certainly mostly a matter of gut health vs inflammation.

We really only have room for that kind of one-line summary here, but do read the paper if you’re interested, as it also talks about other dietary factors that had an impact, with the above-listed items being the topmost impactful factors, but for example (to take just one snippet of many possible ones):

❝In particular, saturated fatty acids (SFA) and cholesterol increased the risk for symptoms❞

~ Ibid. ← so do read it, for many more snippets like this!

What else does and doesn’t work

We covered a little while back the question of whether it is strengthening to hold one’s pee, or better to go whenever one feels the urge, and the answer is clear:

Meanwhile, supplements on the other hand are a mixed bag; there are some that probably help, and others, not so much:

What’s in the supplements that claim to help you cut down on bathroom breaks? And do they work?

Want to do more?

Check out these previous articles of ours:

Pelvic Floor Exercises (Not Kegels!) To Prevent Urinary Incontinence

and

Keeping Your Kidneys Happy: It’s About More Than Just Hydration! ← important at all ages, but especially relevant after 60

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Why rating your pain out of 10 is tricky

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“It’s really sore,” my (Josh’s) five-year-old daughter said, cradling her broken arm in the emergency department.

“But on a scale of zero to ten, how do you rate your pain?” asked the nurse.

My daughter’s tear-streaked face creased with confusion.

“What does ten mean?”

“Ten is the worst pain you can imagine.” She looked even more puzzled.

As both a parent and a pain scientist, I witnessed firsthand how our seemingly simple, well-intentioned pain rating systems can fall flat.

altanaka/Shutterstock What are pain scales for?

The most common scale has been around for 50 years. It asks people to rate their pain from zero (no pain) to ten (typically “the worst pain imaginable”).

This focuses on just one aspect of pain – its intensity – to try and rapidly understand the patient’s whole experience.

How much does it hurt? Is it getting worse? Is treatment making it better?

Rating scales can be useful for tracking pain intensity over time. If pain goes from eight to four, that probably means you’re feeling better – even if someone else’s four is different to yours.

Research suggests a two-point (or 30%) reduction in chronic pain severity usually reflects a change that makes a difference in day-to-day life.

But that common upper anchor in rating scales – “worst pain imaginable” – is a problem.

People usually refer to their previous experiences when rating pain. sasirin pamai/Shutterstock A narrow tool for a complex experience

Consider my daughter’s dilemma. How can anyone imagine the worst possible pain? Does everyone imagine the same thing? Research suggests they don’t. Even kids think very individually about that word “pain”.

People typically – and understandably – anchor their pain ratings to their own life experiences.

This creates dramatic variation. For example, a patient who has never had a serious injury may be more willing to give high ratings than one who has previously had severe burns.

“No pain” can also be problematic. A patient whose pain has receded but who remains uncomfortable may feel stuck: there’s no number on the zero-to-ten scale that can capture their physical experience.

Increasingly, pain scientists recognise a simple number cannot capture the complex, highly individual and multifaceted experience that is pain.

Who we are affects our pain

In reality, pain ratings are influenced by how much pain interferes with a person’s daily activities, how upsetting they find it, their mood, fatigue and how it compares to their usual pain.

Other factors also play a role, including a patient’s age, sex, cultural and language background, literacy and numeracy skills and neurodivergence.

For example, if a clinician and patient speak different languages, there may be extra challenges communicating about pain and care.

Some neurodivergent people may interpret language more literally or process sensory information differently to others. Interpreting what people communicate about pain requires a more individualised approach.

Impossible ratings

Still, we work with the tools available. There is evidence people do use the zero-to-ten pain scale to try and communicate much more than only pain’s “intensity”.

So when a patient says “it’s eleven out of ten”, this “impossible” rating is likely communicating more than severity.

They may be wondering, “Does she believe me? What number will get me help?” A lot of information is crammed into that single number. This patient is most likely saying, “This is serious – please help me.”

In everyday life, we use a range of other communication strategies. We might grimace, groan, move less or differently, use richly descriptive words or metaphors.

Collecting and evaluating this kind of complex and subjective information about pain may not always be feasible, as it is hard to standardise.

As a result, many pain scientists continue to rely heavily on rating scales because they are simple, efficient and have been shown to be reliable and valid in relatively controlled situations.

But clinicians can also use this other, more subjective information to build a fuller picture of the person’s pain.

How can we communicate better about pain?

There are strategies to address language or cultural differences in how people express pain.

Visual scales are one tool. For example, the “Faces Pain Scale-Revised” asks patients to choose a facial expression to communicate their pain. This can be particularly useful for children or people who aren’t comfortable with numeracy and literacy, either at all, or in the language used in the health-care setting.

A vertical “visual analogue scale” asks the person to mark their pain on a vertical line, a bit like imagining “filling up” with pain.

Modified visual scales are sometimes used to try to overcome communication challenges. Nenadmil/Shutterstock What can we do?

Health professionals

Take time to explain the pain scale consistently, remembering that the way you phrase the anchors matters.

Listen for the story behind the number, because the same number means different things to different people.

Use the rating as a launchpad for a more personalised conversation. Consider cultural and individual differences. Ask for descriptive words. Confirm your interpretation with the patient, to make sure you’re both on the same page.

Patients

To better describe pain, use the number scale, but add context.

Try describing the quality of your pain (burning? throbbing? stabbing?) and compare it to previous experiences.

Explain the impact the pain is having on you – both emotionally and how it affects your daily activities.

Parents

Ask the clinician to use a child-suitable pain scale. There are special tools developed for different ages such as the “Faces Pain Scale-Revised”.

Paediatric health professionals are trained to use age-appropriate vocabulary, because children develop their understanding of numbers and pain differently as they grow.

A starting point

In reality, scales will never be perfect measures of pain. Let’s see them as conversation starters to help people communicate about a deeply personal experience.

That’s what my daughter did — she found her own way to describe her pain: “It feels like when I fell off the monkey bars, but in my arm instead of my knee, and it doesn’t get better when I stay still.”

From there, we moved towards effective pain treatment. Sometimes words work better than numbers.

Joshua Pate, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of Technology Sydney; Dale J. Langford, Associate Professor of Pain Management Research in Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University, and Tory Madden, Associate Professor and Pain Researcher, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Healthy Made Simple – by Ella Mills

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Often, cookbooks leave a gap between “add the beans to the rice, then microwave” and “delicately embarrass the green-shooted scallions with assiduous garlic before adding to the matelote of orrazata flamed in Sapient Pear Brandy”. This book fills that gap:

It has dishes good for entertaining, and dishes good for eating on a Tuesday night after a long day. Sometimes, they’re even the same dishes.

It has a focus on what’s pleasing, easy, healthy, and consistent with being cooked in a real home kitchen for real people.

The book offers 75 recipes that:

- Take under 30 minutes to make*

- Contain 10 ingredients or fewer

- Have no more than 5 steps

- Are healthy and packed with goodness

- Are delicious and flavorful

*With a selection for under 15 minutes, too!

A strength of the book is that it’s based on practical, real-world cooking, and as such, there are sections such as “Prep-ahead [meals]”, and “cook once, eat twice”, etc.

Just because one is cooking with simple fresh ingredients doesn’t mean that everything bought today must be used today!

Bottom line: if you’d like simple, healthy recipe ideas that lend themselves well to home-cooking and prepping ahead / enjoying leftovers the next day, this is an excellent book for you.

Click here to check out Healthy Made Simple, enjoy the benefits to your health, the easy way!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How Much Can Hypnotherapy Really Do?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sit Back, Relax, And…

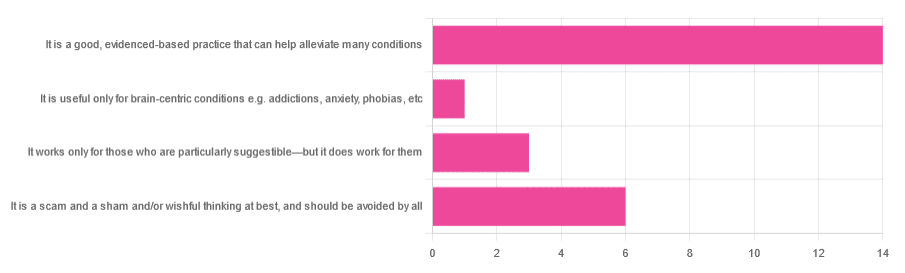

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinions of hypnotherapy, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 58% said “It is a good, evidenced-based practice that can help alleviate many conditions”

- Exactly 25% said “It is a scam and sham and/or wishful thinking at best, and should be avoided by all”

- About 13% said “It works only for those who are particularly suggestible—but it does work for them”

- One (1) person said “It is useful only for brain-centric conditions e.g. addictions, anxiety, phobias, etc”

So what does the science say?

Hypnotherapy is all in the patient’s head: True or False?

True! But guess which part of your body controls much of the rest of it.

So while hypnotherapy may be “all in the head”, its effects are not.

Since placebo effect, nocebo effect, and psychosomatic effect in general are well-documented, it’s quite safe to say at the very least that hypnotherapy thus “may be useful”.

Which prompts the question…

Hypnotherapy is just placebo: True or False?

False, probably. At the very least, if it’s placebo, it’s an unusually effective placebo.

And yes, even though testing against placebo is considered a good method of doing randomized controlled trials, some placebos are definitely better than others. If a placebo starts giving results much better than other placebos, is it still a placebo? Possibly a philosophical question whose answer may be rooted in semantics, but happily we do have a more useful answer…

Here’s an interesting paper which: a) begins its abstract with the strong, unequivocal statement “Hypnosis has proven clinical utility”, and b) goes on to examine the changes in neural activity during hypnosis:

Brain Activity and Functional Connectivity Associated with Hypnosis

It works only for the very suggestible: True or False?

False, broadly. As with any medical and/or therapeutic procedure, a patient’s expectations can affect the treatment outcome.

And, especially worthy of note, a patient’s level of engagement will vastly affect it treatment that has patient involvement. So for example, if a doctor prescribes a patient pills, which the patient does not think will work, so the patient takes them intermittently, because they’re slow to get the prescription refilled, etc, then surprise, the pills won’t get as good results (since they’re often not being taken).

How this plays out in hypnotherapy: because hypnotherapy is a guided process, part of its efficacy relies on the patient following instructions. If the hypnotherapist guides the patient’s mind, and internally the patient is just going “nope nope nope, what a lot of rubbish” then of course it will not work, just like if you ask for directions in the street and then ignore them, you won’t get to where you want to be.

For those who didn’t click on the above link by the way, you might want to go back and have a look at it, because it included groups of individuals with “high/low hypnotizability” per several ways of scoring such.

It works only for brain-centric things, e.g. addictions, anxieties, phobias, etc: True or False?

False—but it is better at those. Here for example is the UK’s Royal College of Psychiatrists’ information page, and if you go to “What conditions can hypnotherapy help to treat”, you’ll see two broad categories; the first is almost entirely brain-stuff; the second is more varied, and includes pain relief of various kinds, burn care, cancer treatment side effects, and even menopause symptoms. Finally, warts and other various skin conditions get their own (positive) mention, per “this is possible through the positive effects hypnosis has on the immune system”:

RCPsych | Hypnosis And Hypnotherapy

Wondering how much psychosomatic effect can do?

You might like this previous article; it’s not about hypnotherapy, but it is about the difference the mind can make on physical markers of aging:

Aging, Counterclockwise: When Age Is A Flexible Number

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What are ‘collarium’ sunbeds? Here’s why you should stay away

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Reports have recently emerged that solariums, or sunbeds – largely banned in Australia because they increase the risk of skin cancer – are being rebranded as “collarium” sunbeds (“coll” being short for collagen).

Commercial tanning and beauty salons in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria are marketing collariums, with manufacturers and operators claiming they provide a longer lasting tan and stimulate collagen production, among other purported benefits.

A collarium sunbed emits both UV radiation and a mix of visible wavelength colours to produce a pink or red light. Like an old-school sunbed, the user lies in it for ten to 20 minute sessions to quickly develop a tan.

But as several experts have argued, the providers’ claims about safety and effectiveness don’t stack up.

Why were sunbeds banned?

Commercial sunbeds have been illegal across Australia since 2016 (except for in the Northern Territory) under state-based radiation safety laws. It’s still legal to sell and own a sunbed for private use.

Their dangers were highlighted by young Australians including Clare Oliver who developed melanoma after using sunbeds. Oliver featured in the No Tan Is Worth Dying For campaign and died from her melanoma at age 26 in 2007.

Sunbeds lead to tanning by emitting UV radiation – as much as six times the amount of UV we’re exposed to from the summer sun. When the skin detects enough DNA damage, it boosts the production of melanin, the brown pigment that gives you the tanned look, to try to filter some UV out before it hits the DNA. This is only partially successful, providing the equivalent of two to four SPF.

Essentially, if your body is producing a tan, it has detected a significant amount of DNA damage in your skin.

Research shows people who have used sunbeds at least once have a 41% increased risk of developing melanoma, while ten or more sunbed sessions led to a 100% increased risk.

In 2008, Australian researchers estimated that each year, sunbeds caused 281 cases of melanoma, 2,572 cases of squamous cell carcinoma (another common type of skin cancer), and $3 million in heath-care costs, mostly to Medicare.

How are collarium sunbeds supposed to be different?

Australian sellers of collarium sunbeds imply they are safe, but their machine descriptions note the use of UV radiation, particularly UVA.

UVA is one part of the spectrum of UV radiation. It penetrates deeper into the skin than UVB. While UVB promotes cancer-causing mutations by discharging energy straight into the DNA strand, UVA sets off damage by creating reactive oxygen species, which are unstable compounds that react easily with many types of cell structures and molecules. These damage cell membranes, protein structures and DNA.

Evidence shows all types of sunbeds increase the risk of melanoma, including those that use only UVA.

Some manufacturers and clinics suggest the machine’s light spectrum increases UV compatibility, but it’s not clear what this means. Adding red or pink light to the mix won’t negate the harm from the UV. If you’re getting a tan, you have a significant amount of DNA damage.

Collagen claims

One particularly odd claim about collarium sunbeds is that they stimulate collagen.

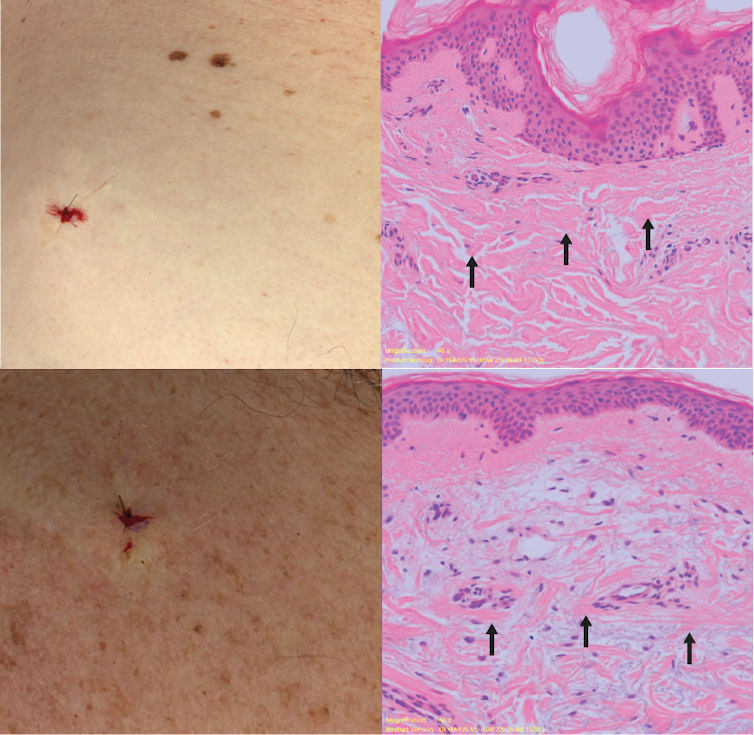

Collagen is the main supportive tissue in our skin. It provides elasticity and strength, and a youthful appearance. Collagen is constantly synthesised and broken down, and when the balance between production and recycling is lost, the skin loses strength and develops wrinkles. The collagen bundles become thin and fragmented. This is a natural part of ageing, but is accelerated by UV exposure.

Sun-protected skin (top) has thick bands of pink collagen (arrows) in the dermis, as seen on microscopic examination. Chronically sun-damaged skin (bottom) has much thinner collagen bands.

Katie Lee/UQThe reactive oxygen species generated by UVA light damage existing collagen structures and kick off a molecular chain of events that downgrades collagen-producing enzymes and increases collagen-destroying enzymes. Over time, a build-up of degraded collagen fragments in the skin promotes even more destruction.

While there is growing evidence red light therapy alone could be useful in wound healing and skin rejuvenation, the UV radiation in collarium sunbeds is likely to undo any benefit from the red light.

What about phototherapy?

There are medical treatments that use controlled UV radiation doses to treat chronic inflammatory skin diseases like psoriasis.

The anti-collagen effects of UVA can also be used to treat thickened scars and keloids. Side-effects of UV phototherapy include tanning, itchiness, dryness, cold sore virus reactivation and, notably, premature skin ageing.

These treatments use the minimum exposure necessary to treat the condition, and are usually restricted to the affected body part to minimise risks of future cancer. They are administered under medical supervision and are not recommended for people already at high risk of skin cancer, such as people with atypical moles.

So what happens now?

It looks like many collariums are just sunbeds rebranded with red light. Queensland Health is currently investigating whether these salons are breaching the state’s Radiation Safety Act, and operators could face large fines.

As the 2024 Australians of the Year – melanoma treatment pioneers Georgina Long and Richard Scolyer – highlighted in their acceptance speech, “there is nothing healthy about a tan”, and we need to stop glamorising tanning.

However, if you’re desperate for the tanned look, there is a safer and easy way to get one – out of a bottle or by visiting a salon for a spray tan.

Katie Lee, PhD Candidate, Dermatology Research Centre, The University of Queensland and Anne Cust, Professor of Cancer Epidemiology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Antihistamines’ Generation Gap

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Are You Ready For Allergy Season?

For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, fall will be upon us soon, and we have a few weeks to be ready for it. A common seasonal ailment is of course seasonal allergies—it’s not serious for most of us, but it can be very annoying, and can disrupt a lot of our normal activities.

Suddenly, a thing that notionally does us no real harm, is making driving dangerous, cooking take three times as long, sex laughable if not off-the-table (so to speak), and the lightest tasks exhausting.

So, what to do about it?

Antihistamines: first generation

Ye olde antihistamines such as diphenhydramine and chlorpheniramine are probably not what to do about it.

They are small molecules that cross the blood-brain barrier and affect histamine receptors in the central nervous system. This will generally get the job done, but there’s a fair bit of neurological friendly-fire going on, and while they will produce drowsiness, the sleep will usually be of poor quality. They also tax the liver rather.

If you are using them and not experiencing unwanted side effects, then don’t let us stop you, but do be aware of the risks.

See also: Long-term use of diphenhydramine ← this is the active ingredient in Benadryl in the US and Canada, but safety regulations in many other countries mean that Benadryl has different, safer active ingredients elsewhere.

Antihistamines: later generations

We’re going to aggregate 2nd gen, 3rd gen, and 4th gen antihistamines here, because otherwise we’ll be writing a history article and we don’t have room for that. But suffice it to say, later generations of antihistamines do not come with the same problems.

Instead of going in all-guns-blazing to the CNS like first-gens, they are more specific in their receptor-targetting, resulting in negligible collateral damage:

Special shout-out to cetirizine and loratadine, which are the drugs behind half the brand names you’ll see on pharmacy shelves around most of the world these days (including many in the US and Canada).

Note that these two are very often discussed in the same sentence, sit next to each other on the shelf, and often have identical price and near-identical packaging. Their effectiveness (usually: moderate) and side effects (usually: low) are similar and comparable, but they are genuinely different drugs that just happen to do more or less the same thing.

This is relevant because if one of them isn’t working for you (and/or is creating an unwanted side effect), you might want to try the other one.

Another honorable mention goes to fexofenadine, for which pretty much all the same as the above goes, though it gets talked about less (and when it does get mentioned, it’s usually by its most popular brand name, Allegra).

Finally, one that’s a little different and also deserving of a special mention is azelastine. It was recently (ish, 2021) moved from being prescription-only to being non-prescription (OTC), and it’s a nasal spray.

It can cause drowsiness, but it’s considered safe and effective for most people. Its main benefit is not really the difference in drug, so much as the difference in the route of administration (nasal rather than oral). Because the drug is in liquid spray form, it can be absorbed through the mucus lining of the nose and get straight to work on blocking the symptoms—in contrast, oral antihistamines usually have to go into your stomach and take their chances there (we say “usually”, because there are some sublingual antihistamines that dissolve under the tongue, but they are less common.)

Better than antihistamines?

Writer’s note: at this point, I was given to wonder: “wait, what was I squirting up my nose last time anyway?”—because, dear readers, at the time I got it I just bought one of every different drug on the shelf, desperate to find something that worked. What worked for me, like magic, when nothing else had, was beclometasone dipropionate, which a) smelled delightfully of flowers, which might just be the brand I got, b) needs replacing now because I got it in March 2023 and it expired July 2024, and c) is not an antihistamine at all.

But, that brings us to the final chapter for today: systemic corticosteroids

They’re not ok for everyone (check with your doctor if unsure), and definitely should not be taken if immunocompromised and/or currently suffering from an infection (including colds, flu, COVID, etc) unless your doctor tells you otherwise (and even then, honestly, double-check).

But! They can work like magic when other things don’t. Unlike antihistamines, which only block the symptoms, systemic corticosteroids tackle the underlying inflammation, which can stop the whole thing in its tracks.

Here’s how they measure up against antihistamines:

❝The results of this systematic review, together with data on safety and cost effectiveness, support the use of intranasal corticosteroids over oral antihistamines as first line treatment for allergic rhinitis.❞

~ Dr. Robert Puy et al.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: