If I’m diagnosed with one cancer, am I likely to get another?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is life-changing and can cause a range of concerns about ongoing health.

Fear of cancer returning is one of the top health concerns. And managing this fear is an important part of cancer treatment.

But how likely is it to get cancer for a second time?

Why can cancer return?

While initial cancer treatment may seem successful, sometimes a few cancer cells remain dormant. Over time, these cancer cells can grow again and may start to cause symptoms.

This is known as cancer recurrence: when a cancer returns after a period of remission. This period could be days, months or even years. The new cancer is the same type as the original cancer, but can sometimes grow in a new location through a process called metastasis.

Actor Hugh Jackman has gone public about his multiple diagnoses of basal cell carcinoma (a type of skin cancer) over the past decade.

The exact reason why cancer returns differs depending on the cancer type and the treatment received. Research is ongoing to identify genes associated with cancers returning. This may eventually allow doctors to tailor treatments for high-risk people.

What are the chances of cancer returning?

The risk of cancer returning differs between cancers, and between sub-types of the same cancer.

New screening and treatment options have seen reductions in recurrence rates for many types of cancer. For example, between 2004 and 2019, the risk of colon cancer recurring dropped by 31-68%. It is important to remember that only someone’s treatment team can assess an individual’s personal risk of cancer returning.

For most types of cancer, the highest risk of cancer returning is within the first three years after entering remission. This is because any leftover cancer cells not killed by treatment are likely to start growing again sooner rather than later. Three years after entering remission, recurrence rates for most cancers decrease, meaning that every day that passes lowers the risk of the cancer returning.

Every day that passes also increases the numbers of new discoveries, and cancer drugs being developed.

What about second, unrelated cancers?

Earlier this year, we learned Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, had been diagnosed with malignant melanoma (a type of skin cancer) shortly after being treated for breast cancer.

Although details have not been confirmed, this is likely a new cancer that isn’t a recurrence or metastasis of the first one.

Australian research from Queensland and Tasmania shows adults who have had cancer have around a 6-36% higher risk of developing a second primary cancer compared to the risk of cancer in the general population.

Who’s at risk of another, unrelated cancer?

With improvements in cancer diagnosis and treatment, people diagnosed with cancer are living longer than ever. This means they need to consider their long-term health, including their risk of developing another unrelated cancer.

Reasons for such cancers include different types of cancers sharing the same kind of lifestyle, environmental and genetic risk factors.

The increased risk is also likely partly due to the effects that some cancer treatments and imaging procedures have on the body. However, this increased risk is relatively small when compared with the (sometimes lifesaving) benefits of these treatment and procedures.

While a 6-36% greater chance of getting a second, unrelated cancer may seem large, only around 10-12% of participants developed a second cancer in the Australian studies we mentioned. Both had a median follow-up time of around five years.

Similarly, in a large US study only about one in 12 adult cancer patients developed a second type of cancer in the follow-up period (an average of seven years).

The kind of first cancer you had also affects your risk of a second, unrelated cancer, as well as the type of second cancer you are at risk of. For example, in the two Australian studies we mentioned, the risk of a second cancer was greater for people with an initial diagnosis of head and neck cancer, or a haematological (blood) cancer.

People diagnosed with cancer as a child, adolescent or young adult also have a greater risk of a second, unrelated cancer.

What can I do to lower my risk?

Regular follow-up examinations can give peace of mind, and ensure any subsequent cancer is caught early, when there’s the best chance of successful treatment.

Maintenance therapy may be used to reduce the risk of some types of cancer returning. However, despite ongoing research, there are no specific treatments against cancer recurrence or developing a second, unrelated cancer.

But there are things you can do to help lower your general risk of cancer – not smoking, being physically active, eating well, maintaining a healthy body weight, limiting alcohol intake and being sun safe. These all reduce the chance of cancer returning and getting a second cancer.

Sarah Diepstraten, Senior Research Officer, Blood Cells and Blood Cancer Division, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and Terry Boyle, Senior Lecturer in Cancer Epidemiology, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Are Waist Trainers Just A Waste, And Are Posture Fixers A Quick Fix?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Are Waist Trainers Just A Waste, And Are Posture Fixers A Quick Fix?

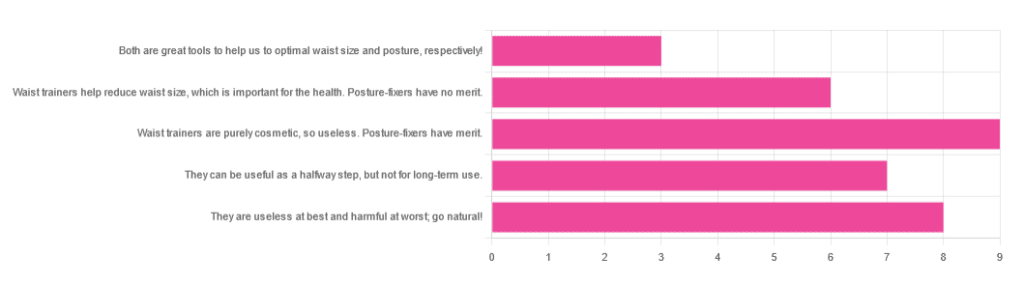

Yesterday, we asked you for your opinions on waist trainers and posture-fixing harnesses, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of results:

- The most popular response was “Waist trainers are purely cosmetic, so useless. Posture-fixers have merit”, with a little over a quarter of the votes.

- The least popular response was “Both are great tools to help us to optimal waist size and posture, respectively!”

- The other three answers each got a little under a quarter of the vote. In terms of discrete data, these were all 7±1, so basically, there was nothing in it.

The sample size was smaller than usual—perhaps the cluster of American holiday dates yesterday and today kept people busy! But, pressing on…

What does the science say?

Waist trainers are purely cosmetic, so, useless. True or False?

True, simply. Honestly, they’re not even that great for cosmetic purposes. They will indeed cinch in your middle, and this shape will be retained for a (very) short while after uncinching, because your organs have been squished inwards and may take a short while to get back to where they are supposed to be.

The American Board of Cosmetic Surgery may not be an unbiased source, but we’re struggling to find scientists who will even touch one of these, so, let’s see what these doctors have to say:

- Waist training can damage vital organs

- You will be slowly suffocating yourself

- Waist training simply doesn’t work

- You cannot drastically change your body shape with a piece of fabric*

Read: ABCS | 4 Reasons to Throw Your Waist Trainer in the Trash

*”But what about foot-binding?”—feet have many bones, whose growth can be physically restricted. Your waist has:

- organs: necessary! (long-term damage possible, but they’re not going away)

- muscles: slightly restrictable! (temporary restriction; no permanent change)

- fat: very squeezable! (temporary muffin; no permanent change)

Posture correctors have merit: True or False?

True—probably, and as a stepping-stone measure only.

The Ergonomics Health Association (a workplace health & safety organization) says:

❝Looking at the clinical evidence of posture correctors, we can say without a doubt that they do work, just not for everyone and not in the same way for all patients.❞

Source: Do Posture Correctors Work? Here’s What Our Experts Think

That’s not very compelling, so we looked for studies, and found… Not much, actually. However, what we did find supported the idea that “they probably do help, but we seriously need better studies with less bias”:

That is also not a compelling title, but here is where it pays to look at the studies and not just the titles. Basically, they found that the results were favorable to the posture-correctors—the science itself was just trash:

❝ The overall findings were that posture-correcting shirts change posture and subjectively have a positive effect on discomfort, energy levels and productivity.

The quality of the included literature was poor to fair with only one study being of good quality. The risk of bias was serious or critical for the included studies. Overall, this resulted in very low confidence in available evidence.❞

Since the benefit of posture correctors like this one is due to reminding the wearer to keep good posture, there is a lot more (good quality!) science for wearable biofeedback tech devices, such as this one:

Spine Cop: Posture Correction Monitor and Assistant

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Pine Nuts vs Macadamia Nuts – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pine nuts to macadamias, we picked the pine nuts.

Why?

In terms of macros, it’s subjective depending on what you want to prioritize; the two nuts are equal in carbs, but pine nuts have more protein and macadamias have more fiber. We’d generally prioritize the fiber, which so far would give macadamias a win in this category, but if you prefer the protein, then consider it pine nuts. Next, we must consider fats; macadamias have slightly more fat, and of which, proportionally more saturated fat, resulting in 3x the total saturated fat compared to pine nuts, gram for gram. With this in mind, we consider this category a tie or a marginal nominal win for pine nuts.

In the category of vitamins, pine nuts have more of vitamins A, B2, B3, B9, E, K, and choline, while macadamias have more of vitamins B1, B5, B6, and C. A clear win for pine nuts this time, especially with pine nuts having more than 17x the vitamin E of macadamias.

When it comes to minerals, pine nuts have more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc, while macadamias have more calcium and selenium. Another easy win for pine nuts.

In short, enjoy either or both (diversity is good), but pine nuts are the healthier by most metrics.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Support For Long COVID & Chronic Fatigue

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Long COVID and Chronic Fatigue

Getting COVID-19 can be very physically draining, so it’s no surprise that getting Long COVID can (and usually does) result in chronic fatigue.

But, what does this mean and what can we do about it?

What makes Long COVID “long”

Long COVID is generally defined as COVID-19 whose symptoms last longer than 28 days, but in reality the symptoms not only tend to last for much longer than that, but also, they can be quite distinct.

Here’s a large (3,762 participants) study of Long COVID, which looked at 203 symptoms:

Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact

Three symptoms stood at out as most prevalent:

- Chronic fatigue (CFS)

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Post-exertional malaise (PEM)

The latter means “the symptoms get worse following physical or mental exertion”.

CFS, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, is also called Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME).

What can be done about it?

The main “thing that people do about it” is to reduce their workload to what they can do, but this is not viable for everyone. Note that work doesn’t just mean “one’s profession”, but anything that requires physical or mental energy, including:

- Childcare

- Housework

- Errand-running

- Personal hygiene/maintenance

For many, this means having to get someone else to do the things—either with support of family and friends, or by hiring help. For many who don’t have those safety nets available, this means things simply not getting done.

That seems bleak; isn’t there anything more we can do?

Doctors’ recommendations are chiefly “wait it out and hope for the best”, which is not encouraging. Some people do recover from Long COVID; for others, it so far appears it might be lifelong. We just don’t know yet.

Doctors also recommend to journal, not for the usual mental health benefits, but because that is data collection. Patients who journal about their symptoms and then discuss those symptoms with their doctors, are contributing to the “big picture” of what Long COVID and its associated ME/CFS look like.

You may notice that that’s not so much saying what doctors can do for you, so much as what you can do for doctors (and in the big picture, eventually help them help people, which might include you).

So, is there any support for individuals with Long COVID ME/CFS?

Medically, no. Not that we could find.

However! Socially, there are grassroots support networks, that may be able to offer direct assistance, or at least point individuals to useful local resources.

Grassroots initiatives include Long COVID SOS and the Patient-Led Research Collaborative.

The patient-led organization Body Politic also used to have such a group, until it shut down due to lack of funding, but they do still have a good resource list:

Click here to check out the Body Politic resource list (it has eight more specific resources)

Stay strong!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Surprising Link Between Type 2 Diabetes & Alzheimer’s

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Surprising Link Between Type 2 Diabetes & Alzheimer’s

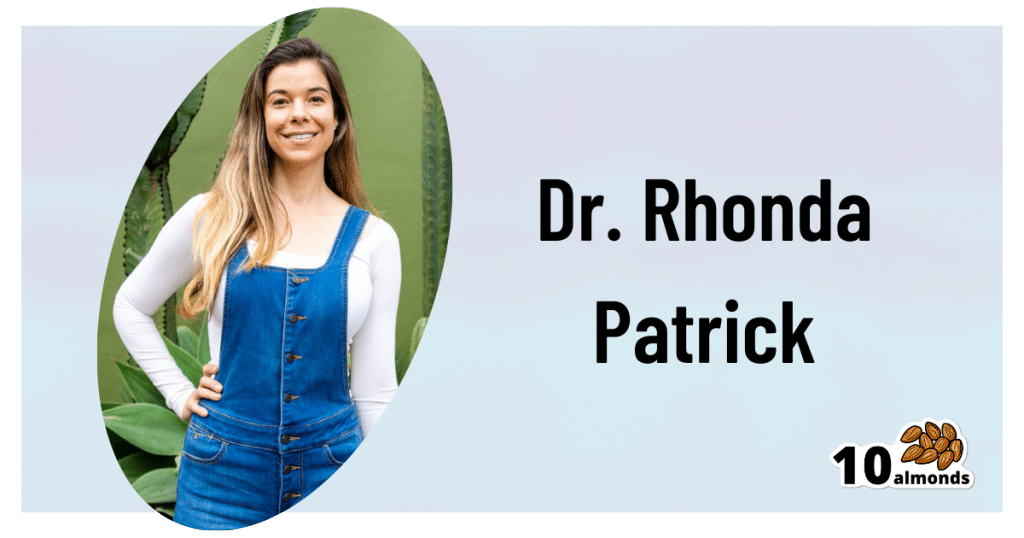

This is Dr. Rhonda Patrick. She’s a biomedical scientist with expertise in the areas of aging, cancer, and nutrition. In the past five years she has expanded her research of aging to focus more on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as she has a genetic predisposition to both.

What does that genetic predisposition look like? People who (like her) have the APOE-ε4 allele have a twofold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease—and if you have two copies (i.e., one from each of two parents), the risk can be up to tenfold. Globally, 13.7% of people have at least one copy of this allele.

So while getting Alzheimer’s or not is not, per se, hereditary… The predisposition to it can be passed on.

What’s on her mind?

Dr. Patrick has noted that, while we don’t know for sure the causes of Alzheimer’s disease, and can make educated guesses only from correlations, the majority of current science seems to be focusing on just one: amyloid plaques in the brain.

This is a worthy area of research, but ignores the fact that there are many potential Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms to explore, including (to count only mainstream scientific ideas):

- The amyloid hypothesis

- The tau hypothesis

- The inflammatory hypothesis

- The cholinergic hypothesis

- The cholesterol hypothesis

- The Reelin hypothesis

- The large gene instability hypothesis

…as well as other strongly correlated factors such as glucose hypometabolism, insulin signalling, and oxidative stress.

If you lost your keys and were looking for them, and knew at least half a dozen places they might be, how often would you check the same place without paying any attention to the others?

To this end, she notes about those latter-mentioned correlated factors:

❝50–80% of people with Alzheimer’s disease have type 2 diabetes; there is definitely something going on❞

There’s another “smoking gun” for this too, because dysfunction in the blood vessels and capillaries that line the blood-brain barrier seem to be a very early event that is common between all types of dementia (including Alzheimer’s) and between type 2 diabetes and APOE-ε4.

Research is ongoing, and Dr. Patrick is at the forefront of that. However, there’s a practical take-away here meanwhile…

What can we do about it?

Dr. Patrick hypothesizes that if we can reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, we may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s with it.

Obviously, avoiding diabetes if possible is a good thing to do anyway, but if we’re aware of an added risk factor for Alzheimer’s, it becomes yet more important.

Of course, all the usual advices apply here, including a Mediterranean diet and regular moderate exercise.

Three other things Dr. Patrick specifically recommends (to reduce both type 2 diabetes risk and to reduce Alzheimer’s risk) include:

(links are to her blog, with lots of relevant science for each)

You can also hear more from Dr. Patrick personally, as a guest on Dr. Peter Attia’s podcast recently. She discusses these topics in much greater detail than we have room for in our newsletter:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Healthy Longevity As A Lifestyle Choice

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

7 Keys To Healthy Longevity

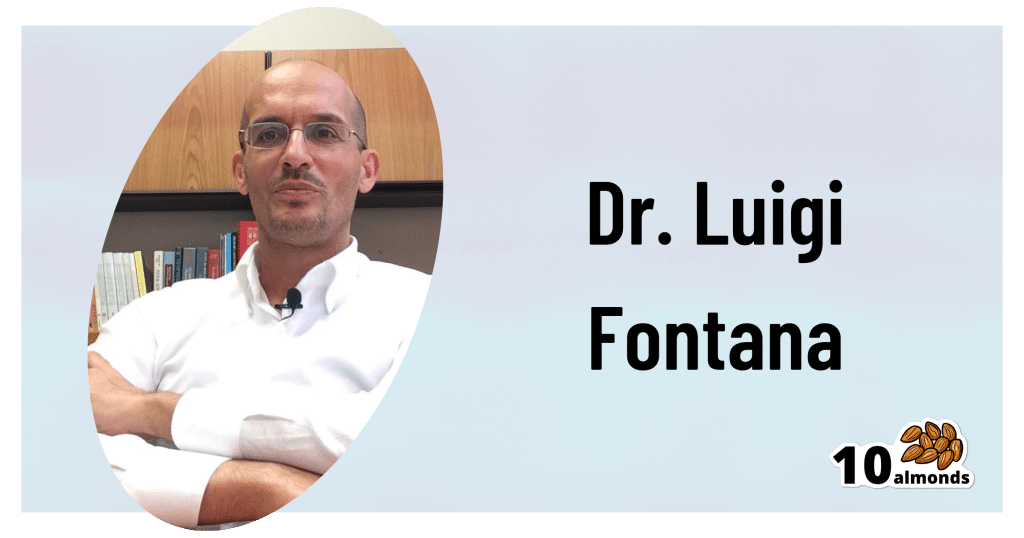

This is Dr. Luigi Fontana. He’s a research professor of Geriatrics & Nutritional Science, and co-director of the Longevity Research Program at Washington University in St. Louis.

What does he want us to know?

He has a many-fold approach to healthy longevity, most of which may not be news to you, but you might want to prioritize some things:

Consider caloric restriction with optimal nutrition (CRON)

This is about reducing the metabolic load on your body, which frees up bodily resources for keeping yourself young.

Keeping your body young and healthy is your body’s favorite thing to do, but it can’t do that if it never gets a chance because of all the urgent metabolic tasks you’re giving it.

If CRON isn’t your thing (isn’t practicable for you, causes undue suffering, etc) then intermittent fasting is a great CR mimetic, and he recommends that too. See also:

- Is Cutting Calories The Key To Healthy Long Life?

- Fasting Without Crashing? We Sort The Science From The Hype

Keep your waistline small

Whichever approach you prefer to use to look after your metabolic health, keeping your waistline down is much more important for health than BMI.

Specifically, he recommends keeping it:

- under 31.5” for women

- under 37” for men

The disparity here is because of hormonal differences that influence both metabolism and fat distribution.

Exercise as part of your lifestyle

For Dr. Fontana, he loves mountain-biking (this writer could never!) and weight-lifting (also not my thing). But what’s key is not the specifics, but what’s going on:

- Some kind of frequent movement

- Some kind of high-intensity interval training

- Some kind of resistance training

Frequent movement because our bodies are evolved to be moving more often than not:

The Doctor Who Wants Us To Exercise Less, & Move More

High-Intensity Interval Training because unlike most forms of exercise (which slow metabolism afterwards to compensate), it boosts metabolism for up to 2 hours after training:

How To Do HIIT (Without Wrecking Your Body)

Resistance training because strength (of muscles and bones) matters too:

Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

Writer’s examples:

So while I don’t care for mountain-biking or weight-lifting, what I do is:

1) movement: walk (briskly!) everywhere and also use a standing desk

2) HIIT: 2-minute bursts of hindu squats and/or exercise bike sprints

3) resistance: pilates and other calisthenicsModeration is not key

Dr. Fontana advises that we do not smoke, and that we do not drink alcohol, for example. He also notes that just as the only healthy amount of alcohol is zero, less ultra-processed food is always better than more.

Maybe you don’t want to abstain completely, but mindful wilful consumption of something unhealthy is preferable to believing “moderate consumption is good for the health” and an unhealthy habit develops!

Greens and beans

Shocking absolutely nobody, Dr. Fontana advocates for (what has been the most evidence-based gold standard of healthy-aging diets for quite some years now) the Mediterranean diet.

See also: Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet ← this is about tweaking the Mediterranean diet per personal area of focus, e.g. anti-inflammatory bonus, best for gut, heart healthiest, and most neuroprotective.

Take it easy

Dr. Fontana advises us (again, with a wealth of evidence) Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and to get good sleep.

Not shocked?

To quote the good doctor,

❝There are no shortcuts. No magic pills or expensive procedures can replace the beneficial effects of a healthy diet, exercise, mindfulness, or a regenerating night’s sleep.❞

Always a good reminder!

Want to know more?

You might enjoy his book “The Path to Longevity: How to Reach 100 with the Health and Stamina of a 40-Year-Old”, which we reviewed previously

You might also like this video of his, about changing the conversation from “chronic disease” to “chronic health”:

Want to watch it, but not right now? Bookmark it for later

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Working Smarter < Working Brighter!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When it comes to working smarter, not harder, there’s plenty of advice and honestly, it’s mostly quite sensible. For example:

(Nice to see they featured a method we talked about last week—great minds!)

But, as standards of productivity rise, the goalposts get moved too, and the treadmill just keeps on going…

- 49% of entrepreneurs say they’ve struggled with some kind of mental illness

- Millennial women are one of the workforce groups at the highest risk of anxiety

- About 7 in 10 millennials experience burnout at work

Not that these things are confined to Millennials, by any stretch, but Millennials make up a huge portion of working people. Ideally, this age group should be able to bring the best of both worlds to the workplace by combining years of experience with youthful energy.

So clearly something is going wrong; the question is: what can be done about it?

Workers of the World, Unwind

A knee-jerk response might be “work to rule”—a tactic long-used by disgruntled exploited workers to do no more than the absolute minimum required to not get fired. And it’s arguably better for them than breaking themselves at work, but that’s not exactly enriching, is it?

This is Brittany Berger, founder of “Work Brighter”.

She’s a content marketing consultant, mental health advocate, and (in her words) a highly ridiculous human who always has a pop culture reference at the ready.

What, besides pop culture references, is she bringing to the table? What is Working Brighter?

❝Working brighter means going beyond generic “work smarter” advice on the internet and personalizing it to work FOR YOU. It means creating your own routines for work, productivity, and self-care.❞

Brittany Berger

Examples of working brighter include…

Asking:

- What would your work involve, if it were more fun?

- How can you make your work more comfortable for you?

- What changes could you make that would make your work more sustainable (i.e., to avoid burnout)?

Remembering:

- Mental health is just health

- Self-care is a “soft skill”

- Rest is work when it’s needed

This is not one of those “what workers really want is not more pay, it’s beanbags” things, by the way (but if you want a beanbag, then by all means, get yourself a beanbag).

It’s about making time to rest, it’s about having the things that make you feel good while you’re working, and making sure you can enjoy working. You’re going to spend a lot of your life doing it; you might as well enjoy it.

❝Nobody goes to their deathbed wishing they’d spent more time at the office❞

Anon

On the contrary, having worked too hard is one of the top reported regrets of the dying!

Article: The Top Five Regrets Of The Dying

And no, they don’t wish they’d “worked smarter, not harder”. They wish (also in the above list, in fact) that they’d had the courage to live a life more true to themselves.

You can do that in your work. Whatever your work is. And if your work doesn’t permit that (be it the evil boss trope, or even that you are the boss and your line of work just doesn’t work that way), time to change that up. Stop focusing on what you can’t do, and look for what you can do.

Spoiler: you can have a blast just trying things out!

That doesn’t mean you should quit your job, or replace your PC with a Playstation, or whatever.

It just means that you deserve comfort and happiness while working, and around your work!

Need a helping hand getting started?

- Create your own self-care plan to avoid burnout

- ⏳ Complete your first “time audit”

- ❣️ Zip through to self-awareness with bullet-journalling

Like A Boss

And pssst, if you’re a business-owner who is thinking “but I have quotas to meet”, your customers are going to love your staff being happier, and will enjoy their interactions with your company much more. Or if your staff aren’t customer-facing, then still, they’ll work better when they enjoy doing it. This isn’t rocket science, but all too many companies give a cursory nod to it before proceeding to ignore it for the rest of the life of the company.

So where do you start, if you’re in those particular shoes?

Read on…

*straightens tie because this is the serious bit* —just kidding, I’m wearing my comfiest dress and fluffy-lined slipper-socks. But that makes this absolutely no less serious:

The Institute for Health and Productivity Management (IHPM) and WorkPlace Wellness Alliance (WPWA) might be a good place to get you on the right track!

❝IHPM/WPWA is a global nonprofit enterprise devoted to establishing the full economic value of employee health as a business asset—a neglected investment in the increased productivity of human capital.

IHPM helps employers identify the full economic cost impact of employee health issues on business performance, design and implement the best programs to reduce this impact by improving functional health and productivity, and measure the success of their efforts in financial terms.❞

The Institute for Health and Productivity Management

They offer courses and consultations, but they also have free downloadables and videos, which are awesome and in many cases may already be enough to seriously improve things for your business already:

Check Out IHPM’s Resources Here!

What can you do to make your working life better for you? We’d love to hear about any changes you make inspired by Brittany’s work—you can always just hit reply, and we’re always glad to hear from you!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: