How to Vary Breakfast for Digestion?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Would appreciate your thoughts on how best to promote good digestion. For years, my breakfast has consisted of flaxseeds, sunflower seeds, and almonds – all well ground up – eaten with a generous amount of kefir. This works a treat as far as my digestion is concerned. But I sometimes wonder whether it would be better for my health if I varied or supplemented this breakfast. How might I do this without jeopardising my good digestion?❞

Sounds like you’re already doing great! Those ingredients are all very nutrient-dense, and grinding them up improves digestion greatly, to the point that you’re getting nutrients your body couldn’t get at otherwise. And the kefir, of course, is a top-tier probiotic.

Also, you’re getting plenty of protein and healthy fats in with your carbs, which results in the smoothest blood sugar curve.

As for variety…

Variety is good in diet, but variety within a theme. Our gut microbiota change according to what we eat, so sudden changes in diet are often met with heavy resistance from our gut.

- For example, people who take up a 100% plant-based diet overnight often spend the next day in the bathroom, and wonder what happened.

- Conversely, a long-time vegan who (whether by accident or design) consumes meat or dairy will likely find themself quickly feeling very unwell, because their gut microbiota have no idea what to do with this.

So, variety yes, but within a theme, and make any changes gradual for the easiest transition.

All in all, the only obvious suggestion for improvement is to consider adding some berries. These can be fresh, dried, or frozen, and will confer many health benefits (most notably a lot of antioxidant activity).

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

“You Just Need to Lose Weight” And 19 Other Myths About Fat People – by Aubrey Gordon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed another book by this author, “What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat”, and this time, she’s doing some important mythbusting.

The titular “you just need to lose weight” is a commonly-taken easy-out for many doctors, to avoid having to dispense actual treatment for an actual condition. Whether or not weight loss would help in a given situation is often immaterial; “kicking the can down the road” is the goal.

Most of the book is divided into 20 chapters, each of them devoted to debunking one myth. Think of it like 10almonds’ “Mythbusting Friday” edition (indeed, we did one about obesity), but with an entire book, and as much room as she needs to provide much more detail than we can ever get into in a single article.

And far from being a mere polemic, she does indeed provide that detail—this is clearly a very well-researched book, above and beyond the author’s own personal experience. Further, all the key points are illustrated and articulated clearly, making the book’s ideas very comprehensible.

The style is pop-science, but with frequent bibliographical references for relevant sources.

Bottom line: for some readers, this book will come as a great validation; for others, it may be eye-opening. Either way, it’s a very worthwhile read.

Share This Post

The Worry Trick – by Dr. David Carbonell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Worry is a time-sink that rarely does us any good, and often does us harm. Many books have been written on how to fight anxiety… That’s not what this book’s about.

Dr. David Carbonell, in contrast, encourages the reader to stop trying to avoid/resist anxiety, and instead, lean into it in a way that detoothes it.

He offers various ways of doing this, from scheduling time to worry, to substituting “what if…” with “let’s pretend…”, and guides the reader through exercises to bring about a sort of worry-desensitization.

The style throughout is very much pop-psychology and is very readable.

If the book has a weak point, it’s that it tends to focus on worrying less about unlikely outcomes, rather than tackling worry that occurs relating to outcomes that are likely, or even known in advance. However, some of the techniques will work for such also! That’s when Dr. Carbonell draws from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Bottom line: if you would like to lose less time and energy to worrying, then this is a fine book for you.

Click here to check out The Worry Trick, and repurpose your energy reserves!

Share This Post

New research suggests intermittent fasting increases the risk of dying from heart disease. But the evidence is mixed

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Kaitlin Day, RMIT University and Sharayah Carter, RMIT University

Intermittent fasting has gained popularity in recent years as a dietary approach with potential health benefits. So you might have been surprised to see headlines last week suggesting the practice could increase a person’s risk of death from heart disease.

The news stories were based on recent research which found a link between time-restricted eating, a form of intermittent fasting, and an increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, or heart disease.

So what can we make of these findings? And how do they measure up with what else we know about intermittent fasting and heart disease?

The study in question

The research was presented as a scientific poster at an American Heart Association conference last week. The full study hasn’t yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The researchers used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a long-running survey that collects information from a large number of people in the United States.

This type of research, known as observational research, involves analysing large groups of people to identify relationships between lifestyle factors and disease. The study covered a 15-year period.

It showed people who ate their meals within an eight-hour window faced a 91% increased risk of dying from heart disease compared to those spreading their meals over 12 to 16 hours. When we look more closely at the data, it suggests 7.5% of those who ate within eight hours died from heart disease during the study, compared to 3.6% of those who ate across 12 to 16 hours.

We don’t know if the authors controlled for other factors that can influence health, such as body weight, medication use or diet quality. It’s likely some of these questions will be answered once the full details of the study are published.

It’s also worth noting that participants may have eaten during a shorter window for a range of reasons – not necessarily because they were intentionally following a time-restricted diet. For example, they may have had a poor appetite due to illness, which could have also influenced the results.

Other research

Although this research may have a number of limitations, its findings aren’t entirely unique. They align with several other published studies using the NHANES data set.

For example, one study showed eating over a longer period of time reduced the risk of death from heart disease by 64% in people with heart failure.

Another study in people with diabetes showed those who ate more frequently had a lower risk of death from heart disease.

A recent study found an overnight fast shorter than ten hours and longer than 14 hours increased the risk dying from of heart disease. This suggests too short a fast could also be a problem.

But I thought intermittent fasting was healthy?

There are conflicting results about intermittent fasting in the scientific literature, partly due to the different types of intermittent fasting.

There’s time restricted eating, which limits eating to a period of time each day, and which the current study looks at. There are also different patterns of fast and feed days, such as the well-known 5:2 diet, where on fast days people generally consume about 25% of their energy needs, while on feed days there is no restriction on food intake.

Despite these different fasting patterns, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) consistently demonstrate benefits for intermittent fasting in terms of weight loss and heart disease risk factors (for example, blood pressure and cholesterol levels).

RCTs indicate intermittent fasting yields comparable improvements in these areas to other dietary interventions, such as daily moderate energy restriction.

There are a variety of intermittent fasting diets. Fauxels/Pexels So why do we see such different results?

RCTs directly compare two conditions, such as intermittent fasting versus daily energy restriction, and control for a range of factors that could affect outcomes. So they offer insights into causal relationships we can’t get through observational studies alone.

However, they often focus on specific groups and short-term outcomes. On average, these studies follow participants for around 12 months, leaving long-term effects unknown.

While observational research provides valuable insights into population-level trends over longer periods, it relies on self-reporting and cannot demonstrate cause and effect.

Relying on people to accurately report their own eating habits is tricky, as they may have difficulty remembering what and when they ate. This is a long-standing issue in observational studies and makes relying only on these types of studies to help us understand the relationship between diet and disease challenging.

It’s likely the relationship between eating timing and health is more complex than simply eating more or less regularly. Our bodies are controlled by a group of internal clocks (our circadian rhythm), and when our behaviour doesn’t align with these clocks, such as when we eat at unusual times, our bodies can have trouble managing this.

So, is intermittent fasting safe?

There’s no simple answer to this question. RCTs have shown it appears a safe option for weight loss in the short term.

However, people in the NHANES dataset who eat within a limited period of the day appear to be at higher risk of dying from heart disease. Of course, many other factors could be causing them to eat in this way, and influence the results.

When faced with conflicting data, it’s generally agreed among scientists that RCTs provide a higher level of evidence. There are too many unknowns to accept the conclusions of an epidemiological study like this one without asking questions. Unsurprisingly, it has been subject to criticism.

That said, to gain a better understanding of the long-term safety of intermittent fasting, we need to be able follow up individuals in these RCTs over five or ten years.

In the meantime, if you’re interested in trying intermittent fasting, you should speak to a health professional first.

Kaitlin Day, Lecturer in Human Nutrition, RMIT University and Sharayah Carter, Lecturer Nutrition and Dietetics, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

Do We Need Supplements, And Do They Work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Does our diet need a little help?

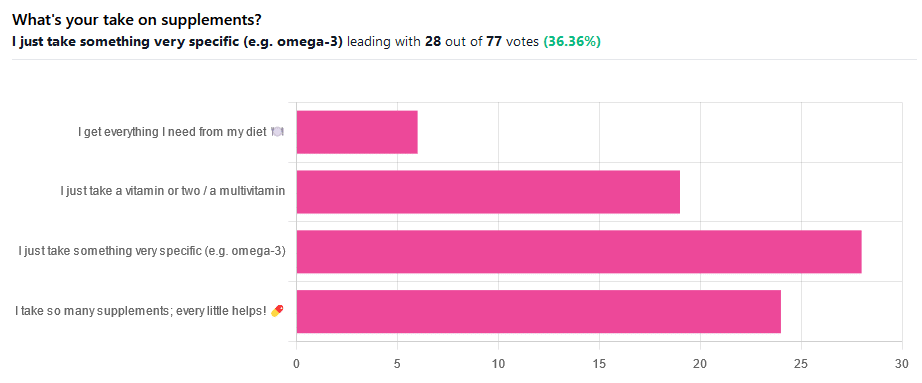

We asked you for your take on supplements, and got the above-illustrated, below-described set of results.

- The largest minority of respondents (a little over a third) voted for “I just take something very specific”

- The next most respondents voted for “I take so many supplements; every little helps!”

- Almost as many voted for “I just take a vitamin or two / a multivitamin”

- Fewest, about 8%, voted for “I get everything I need from my diet”

But what does the science say?

Food is less nutritious now than it used to be: True or False?

True or False depending on how you measure it.

An apple today and an apple from a hundred years ago are likely to contain the same amounts of micronutrients per apple, but a lower percentage of micronutrients per 100g of apple.

The reason for this is that apples (and many other food products; apples are just an arbitrary example) have been selectively bred (and in some cases, modified) for size, and because the soil mineral density has remained the same, the micronutrients per apple have not increased commensurate to the increase in carbohydrate weight and/or water weight. Thus, the resultant percentage will be lower, despite the quantity remaining the same.

We’re going to share some science on this, and/but would like to forewarn readers that the language of this paper is a bit biased, as it looks to “debunk” claims of nutritional values dropping while skimming over “yes, they really have dropped percentage-wise” in favor of “but look, the discrete mass values are still the same, so that’s just a mathematical illusion”.

The reality is, it’s no more a mathematical illusion than is the converse standpoint of saying the nutritional value is the same, despite the per-100g values dropping. After all, sometimes we eat an apple as-is; sometimes we buy a bag of frozen chopped fruit. That 500g bag of chopped fruit is going to contain less copper (for example) than one from decades past.

Here’s the paper, and you’ll see what we mean:

Supplements aren’t absorbed properly and thus are a waste of money: True or False?

True or False depending on the supplement (and your body, and the rest of your diet)

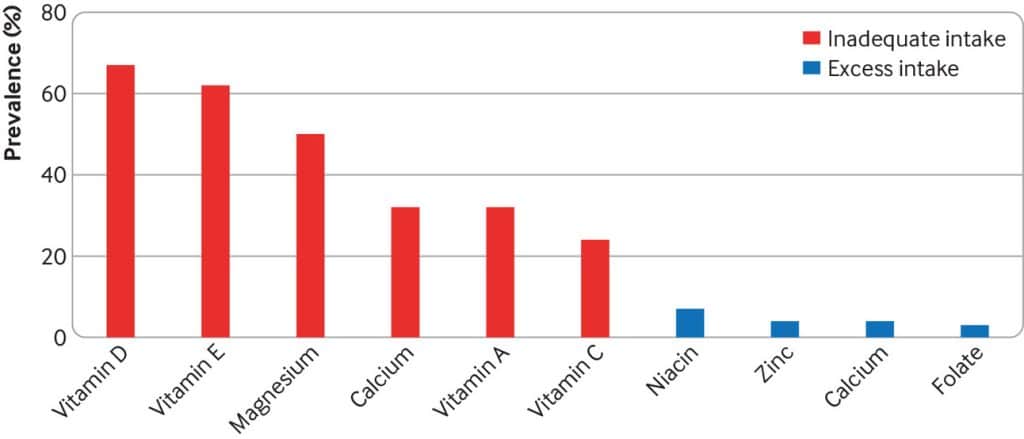

Many people are suffering from dietary deficiencies of vitamins and minerals, that could be easily correctable by supplementation:

However, as this study by Dr. Fang Fang Zhang shows, a lot of vitamin and mineral supplementation does not appear to have much of an effect on actual health outcomes, vis-à-vis specific diseases. She looks at:

- Cardiovascular disease

- Cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Osteoporosis

Her key take-aways from this study were:

- Randomised trial evidence does not support use of vitamin, mineral, and fish oil supplements to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases

- People using supplements tend to be older, female, and have higher education, income, and healthier lifestyles than people who do not use them

- Use of supplements appreciably reduces the prevalence of inadequate intake for most nutrients but also increases the prevalence of excess intake for some nutrients

- Further research is needed to assess the long term effects of supplements on the health of the general population and in individuals with specific nutritional needs, including those from low and middle income countries

Read her damning report: Health effects of vitamin and mineral supplements

On the other hand…

This is almost entirely about blanket vitamin-and-mineral supplementation. With regard to fish oil supplementation, many commercial fish oil supplements break down in the stomach rather than the intestines, and don’t get absorbed well. Additionally, many people take them in forms that aren’t pleasant, and thus result in low adherence (i.e., they nominally take them, but in fact they just sit on the kitchen counter for a year).

One thing we can conclude from this is that it’s good to check the science for any given supplement before taking it, and know what it will and won’t help for. Our “Monday Research Review” editions of 10almonds do this a lot, although we tend to focus on herbal supplements rather than vitamins and minerals.

We can get everything we need from our diet: True or False?

Contingently True (but here be caveats)

In principle, if we eat the recommended guideline amounts of various macro- and micro-nutrients, we will indeed get all that we are generally considered to need. Obviously.

However, this may come with:

- Make sure to get enough protein… Without too much meat, and also without too much carbohydrate, such as from most plant sources of protein

- Make sure to get enough carbohydrates… But only the right kinds, and not too much, nor at the wrong time, and without eating things in the wrong order

- Make sure to get enough healthy fats… Without too much of the unhealthy fats that often exist in the same foods

- Make sure to get the right amount of vitamins and minerals… We hope you have your calculators out to get the delicate balance of calcium, magnesium, potassium, phosphorus, and vitamin D right.

That last one’s a real pain, by the way. Too much or too little of one or another and the whole set start causing problems, and several of them interact with several others, and/or compete for resources, and/or are needed for the others to do their job.

And, that’s hard enough to balance when you’re taking supplements with the mg/µg amount written on them, never mind when you’re juggling cabbages and sardines.

On the topic of those sardines, don’t forget to carefully balance your omega-3, -6, and -9, and even within omega-3, balancing ALA, EPA, and DHA, and we hope you’re juggling those HDL and LDL levels too.

So, when it comes to getting everything we need from our diet, for most of us (who aren’t living in food deserts and/or experiencing food poverty, or having a medical condition that restricts our diet), the biggest task is not “getting enough”, it’s “getting enough of the right things without simultaneously overdoing it on the others”.

With supplements, it’s a lot easier to control what we’re putting in our bodies.

And of course, unless our diet includes things that usually can’t be bought in supermarkets, we’re not going to get the benefits of taking, as a supplement, such things as:

Etc.

So, there definitely are supplements with strong science-backed benefits, that probably can’t be found on your plate!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Plant-Based Healthy Cream Cheese

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cream cheese is a delicious food, and having a plant-based diet isn’t a reason to miss out. Here we have a protein-forward nuts-based cream cheese that we’re sure you’ll love (unless you’re allergic to nuts, in which case, maybe skip this one).

You will need

- 1½ cups raw cashews, soaked in warm water and then drained

- ½ cup water

- ½ cup coconut cream

- Juice of ½ lemon

- 3 tbsp nutritional yeast

- ½ tsp onion powder

- ½ tsp garlic powder

- ½ tsp black pepper

- ½ tsp cayenne pepper

- ¼ tsp MSG, or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

- Optional: ⅓ cup fresh basil

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Blend all of the ingredients until creamy.

2) Optional: leave on the countertop, covered, for 1–2 hours, if you want a more fermented (effectively: cheesy) taste.

3) Refrigerate, ideally overnight, before serving. Serving on bagels is a classic, but you can also enjoy with the Healthy Homemade Flatbreads we made yesterday

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Pistachios vs Cashews – Which is Healthier? ← Pistachios actually won here, but cashews are also great and are better (from a culinary perspective) for making cream cheese

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Spinach vs Kale – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing spinach to kale, we picked the spinach.

Why?

In terms of macros, spinach and kale are very similar. They are mostly water wrapped in fiber, with very small amounts of carbohydrates and protein and trace amounts of fat.

Spinach has a lot more vitamins and minerals—a wider variety, and in most cases, more of them.

Kale is notably higher in vitamin C, though. Everything else, spinach is higher or close to equal.

Spinach is especially notably a lot higher in B vitamins, as well as iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc.

One downside to spinach, though, which is that it’s high in oxalates, which can increase the risk of kidney stones. If your kidneys are in good health and you eat spinach in moderation, this is not a problem for most people—but if your kidneys aren’t in good health (or you are, for whatever reason, consuming Popeye levels of spinach), you might consider switching to kale.

While spinach swept the board in most categories, kale remains a very good option too, and a diet diverse in many kinds of plants is usually best.

Want to learn more?

Spinach and kale are very both good sources of carotenoids; check out:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: