State Regulators Know Health Insurance Directories Are Full of Wrong Information. They’re Doing Little to Fix It.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Series: America’s Mental Barrier:How Insurers Interfere With Mental Health Care

- Extensive Errors: Many states have sought to make insurers clean up their health plans’ provider directories over the past decade. But the errors are still widespread.

- Paltry Penalties: Most state insurance agencies haven’t issued a fine for provider directory errors since 2019. When companies have been penalized, the fines have been small and sporadic.

- Ghostbusters: Experts said that stricter regulations and stronger fines are needed to protect insurance customers from these errors, which are at the heart of so-called ghost networks.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

To uncover the truth about a pernicious insurance industry practice, staffers with the New York state attorney general’s office decided to tell a series of lies.

So, over the course of 2022 and 2023, they dialed hundreds of mental health providers in the directories of more than a dozen insurance plans. Some staffers pretended to call on behalf of a depressed relative. Others posed as parents asking about their struggling teenager.

They wanted to know two key things about the supposedly in-network providers: Do you accept insurance? And are you accepting new patients?

The more the staffers called, the more they realized that the providers listed either no longer accepted insurance or had stopped seeing new patients. That is, if they heard back from the providers at all.

In a report published last December, the office described rampant evidence of these “ghost networks,” where health plans list providers who supposedly accept that insurance but who are not actually available to patients. The report found that 86% of the listed mental health providers who staffers had called were “unreachable, not in-network, or not accepting new patients.” Even though insurers are required to publish accurate directories, New York Attorney General Letitia James’ office didn’t find evidence that the state’s own insurance regulators had fined any insurers for their errors.

Shortly after taking office in 2021, Gov. Kathy Hochul vowed to combat provider directory misinformation, so there seemed to be a clear path to confronting ghost networks.

Yet nearly a year after the publication of James’ report, nothing has changed. Regulators can’t point to a single penalty levied for ghost networks. And while a spokesperson for New York state’s Department of Financial Services has said that “nation-leading consumer protections” are in the works, provider directories in the state are still rife with errors.

A similar pattern of errors and lax enforcement is happening in other states as well.

In Arizona, regulators called hundreds of mental health providers listed in the networks of the state’s most popular individual health plans. They couldn’t schedule visits with nearly 2 out of every 5 providers they called. None of those companies have been fined for their errors.

In Massachusetts, the state attorney general investigated alleged efforts by insurers to restrict their customers’ mental health benefits. The insurers agreed to audit their mental health provider listings but were largely allowed to police themselves. Insurance regulators have not fined the companies for their errors.

In California, regulators received hundreds of complaints about provider listings after one of the nation’s first ghost network regulations took effect in 2016. But under the new law, they have actually scaled back on fining insurers. Since 2016, just one plan was fined — a $7,500 penalty — for posting inaccurate listings for mental health providers.

ProPublica reached out to every state insurance commission to see what they have done to curb rampant directory errors. As part of the country’s complex patchwork of regulations, these agencies oversee plans that employers purchase from an insurer and that individuals buy on exchanges. (Federal agencies typically oversee plans that employers self-fund or that are funded by Medicare.)

Spokespeople for the state agencies told ProPublica that their “many actions” resulted in “significant accountability.” But ProPublica found that the actual actions taken so far do not match the regulators’ rhetoric.

“One of the primary reasons insurance commissions exist is to hold companies accountable for what they are advertising in their contracts,” said Dr. Robert Trestman, a leading American Psychiatric Association expert who has testified about ghost networks to the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance. “They’re not doing their job. If they were, we would not have an ongoing problem.”

Most states haven’t fined a single company for publishing directory errors since 2019. When they do, the penalties have been small and sporadic. In an average year, fewer than a dozen fines are issued by insurance regulators for directory errors, according to information obtained by ProPublica from almost every one of those agencies. All those fines together represent a fraction of 1% of the billions of dollars in profits made by the industry’s largest companies. Health insurance experts told ProPublica that the companies treat the fines as a “cost of doing business.”

Insurers acknowledge that errors happen. Providers move. They retire. Their open appointments get booked by other patients. The industry’s top trade group, AHIP, has told lawmakers that companies contact providers to verify that their listings are accurate. The trade group also has stated that errors could be corrected faster if the providers did a better job updating their listings.

But providers have told us that’s bogus. Even when they formally drop out of a network, they’re not always removed from the insurer’s lists.

The harms from ghost networks are real. ProPublica reported on how Ravi Coutinho, a 36-year-old entrepreneur from Arizona, had struggled for months to access the mental health and addiction treatment that was covered by his health plan. After nearly two dozen calls to the insurer and multiple hospitalizations, he couldn’t find a therapist. Last spring, he died, likely due to complications from excessive drinking.

Health insurance experts said that, unless agencies can crack down and issue bigger fines, insurers will keep selling error-ridden plans.

“You can have all the strong laws on the books,” said David Lloyd, chief policy officer with the mental health advocacy group Inseparable. “But if they’re not being enforced, then it’s kind of all for nothing.”

The problem with ghost networks isn’t one of awareness. States, federal agencies, researchers and advocates have documented them time and again for years. But regulators have resisted penalizing insurers for not fixing them.

Two years ago, the Arizona Department of Insurance and Financial Institutions began to probe the directories used by five large insurers for plans that they sold on the individual market. Regulators wanted to find out if they could schedule an appointment with mental health providers listed as accepting new patients, so their staff called 580 providers in those companies’ directories.

Thirty-seven percent of the calls did not lead to an appointment getting scheduled.

Even though this secret-shopper survey found errors at a lower rate than what had been found in New York, health insurance experts who reviewed Arizona’s published findings said that the results were still concerning.

Ghost network regulations are intended to keep provider listings as close to error-free as possible. While the experts don’t expect any insurer to have a perfect directory, they said that double-digit error rates can be harmful to customers.

Arizona’s regulators seemed to agree. In a January 2023 report, they wrote that a patient could be clinging to the “last few threads of hope, which could erode if they receive no response from a provider (or cannot easily make an appointment).”

Secret-shopper surveys are considered one of the best ways to unmask errors. But states have limited funding, which restricts how often they can conduct that sort of investigation. Michigan, for its part, mostly searches for inaccuracies as part of an annual review of a health plan. Nevada investigates errors primarily if someone files a complaint. Christine Khaikin, a senior health policy attorney for the nonprofit advocacy group Legal Action Center, said fewer surveys means higher odds that errors go undetected.

Some regulators, upon learning that insurers may not be following the law, still take a hands-off approach with their enforcement. Oregon’s Department of Consumer and Business Services, for instance, conducts spot checks of provider networks to see if those listings are accurate. If they find errors, insurers are asked to fix the problem. The department hasn’t issued a fine for directory errors since 2019. A spokesperson said the agency doesn’t keep track of how frequently it finds network directory errors.

Dave Jones, a former insurance commissioner in California, said some commissioners fear that stricter enforcement could drive companies out of their states, leaving their constituents with fewer plans to choose from.

Even so, staffers at the Arizona Department of Insurance and Financial Institutions wrote in the report that there “needs to be accountability from insurers” for the errors in their directories. That never happened, and the agency concealed the identities of the companies in the report. A department spokesperson declined to provide the insurers’ names to ProPublica and did not answer questions about the report.

Since January 2023, Arizonans have submitted dozens of complaints to the department that were related to provider networks. The spokesperson would not say how many were found to be substantiated, but the department was able to get insurers to address some of the problems, documents obtained through an open records request show.

According to the department’s online database of enforcement actions, not a single one of those companies has been fined.

Sometimes, when state insurance regulators fail to act, attorneys general or federal regulators intervene in their stead. But even then, the extra enforcers haven’t addressed the underlying problem.

For years, the Massachusetts Division of Insurance didn’t fine any company for ghost networks, so the state attorney general’s office began to investigate whether insurers had deceived consumers by publishing inaccurate directories. Among the errors identified: One plan had providers listed as accepting new patients but no actual appointments were available for months; another listed a single provider more than 10 times at different offices.

In February 2020, Maura Healey, who was then the Massachusetts attorney general, announced settlements with some of the state’s largest health plans. No insurer admitted wrongdoing. The companies, which together collect billions in premiums each year, paid a total of $910,000. They promised to remove providers who left their networks within 30 days of learning about that decision. Healey declared that the settlements would lead to “unprecedented changes to help ensure patients don’t have to struggle to find behavioral health services.”

But experts who reviewed the settlements for ProPublica identified a critical shortcoming. While the insurers had promised to audit directories multiple times a year, the companies did not have to report those findings to the attorney general’s office. Spokespeople for Healey and the attorney general’s office declined to answer questions about the experts’ assessments of the settlements.

After the settlements were finalized, Healey became the governor of Massachusetts and has been responsible for overseeing the state’s insurance division since she took office in January 2023. Her administration’s regulators haven’t brought any fines over ghost networks.

Healey’s spokesperson declined to answer questions and referred ProPublica to responses from the state’s insurance division. A division spokesperson said the state has taken steps to strengthen its provider directory regulations and streamline how information about in-network providers gets collected. Starting next year, the spokesperson said that the division “will consider penalties” against any insurer whose “provider directory is found to be materially noncompliant.”

States that don’t have ghost network laws have seen federal regulators step in to monitor directory errors.

In late 2020, Congress passed the No Surprises Act, which aimed to cut down on the prevalence of surprise medical bills from providers outside of a patient’s insurance network. Since then, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which oversees the two large public health insurance programs, has reached out to every state to see which ones could handle enforcement of the federal ghost network regulations.

At least 15 states responded that they lacked the ability to enforce the new regulation. So CMS is now tasked with watching out for errors in directories used by millions of insurance customers in those states.

Julie Brookhart, a spokesperson for CMS, told ProPublica that the agency takes enforcement of the directory error regulations “very seriously.” She said CMS has received a “small number” of provider directory complaints, which the agency is in the process of investigating. If it finds a violation, Brookhart said regulators “will take appropriate enforcement action.”

But since the requirement went into effect in January 2022, CMS hasn’t fined any insurer for errors. Brookhart said that CMS intends to develop further guidelines with other federal agencies. Until that happens, Brookhart said that insurers are expected to make “good-faith” attempts to follow the federal provider directory rules.

Last year, five California lawmakers proposed a bill that sought to get rid of ghost networks around the state. If it passed, AB 236 would limit the number of errors allowed in a directory — creating a cap of 5% of all providers listed — and raise penalties for violations. California would become home to one of the nation’s toughest ghost network regulations.

The state had already passed one of America’s first such regulations in 2015, requiring insurers to post directories online and correct inaccuracies on a weekly basis.

Since the law went into effect in 2016, insurance customers have filed hundreds of complaints with the California Department of Managed Health Care, which oversees health plans for nearly 30 million enrollees statewide.

Lawyers also have uncovered extensive evidence of directory errors. When San Diego’s city attorney, Mara Elliott, sued several insurers over publishing inaccurate directories in 2021, she based the claims on directory error data collected by the companies themselves. Citing that data, the lawsuits noted that error rates for the insurers’ psychiatrist listings were between 26% and 83% in 2018 and 2019. The insurers denied the accusations and convinced a judge to dismiss the suits on technical grounds. A panel of California appeals court judges recently reversed those decisions; the cases are pending.

The companies have continued to send that data to the DMHC each year — but the state has not used it to examine ghost networks. California is among the states that typically waits for a complaint to be filed before it investigates errors.

“The industry doesn’t take the regulatory penalties seriously because they’re so low,” Elliott told ProPublica. “It’s probably worth it to take the risk and see if they get caught.”

California’s limited enforcement has resulted in limited fines. Over the past eight years, the DMHC has issued just $82,500 in fines for directory errors involving providers of any kind. That’s less than one-fifth of the fines issued in the two years before the regulation went into effect.

A spokesperson for the DMHC said its regulators continue “to hold health plans accountable” for violating ghost network regulations. Since 2018, the DMHC has discovered scores of problems with provider directories and pushed health plans to correct the errors. The spokesperson said that the department’s oversight has also helped some customers get reimbursed for out-of-network costs incurred due to directory errors.

“A lower fine total does not equate to a scaling back on enforcement,” the spokesperson said.

Dr. Joaquin Arambula, one of the state Assembly members who co-sponsored AB 236, disagreed. He told ProPublica that California’s current ghost network regulation is “not effectively being enforced.” After clearing the state Assembly this past winter, his bill, along with several others that address mental health issues, was suddenly tabled this summer. The roadblock came from a surprising source: the administration of the state’s Democratic governor.

Officials with the DMHC, whose director was appointed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, estimated that more than $15 million in extra funding would be needed to carry out the bill’s requirements over the next five years. State lawmakers accused officials of inflating the costs. The DMHC’s spokesperson said that the estimate was accurate and based on the department’s “real experience” overseeing health plans.

Arambula and his co-sponsors hope that their colleagues will reconsider the measure during next year’s session. Sitting before state lawmakers in Sacramento this year, a therapist named Sarah Soroken told the story of a patient who had called 50 mental health providers in her insurer’s directory. None of them could see her. Only after the patient attempted suicide did she get the care she’d sought.

“We would be negligent,” Soroken told the lawmakers, “if we didn’t do everything in our power to ensure patients get the health care they need.”

Paige Pfleger of WPLN/Nashville Public Radio contributed reporting.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Hard to Kill – by Dr. Jaime Seeman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written before about Dr. Seeman’s method for robust health at all ages, focussing on:

- Nutrition

- Movement

- Sleep

- Mindset

- Environment

In this book, she expands on these things far more than we have room to in our little newsletter, including (importantly!) how each interplays with the others. She also follows up with an invitation to take the “Hard to Kill 30-Day Challenge”.

That said, in the category of criticism, it’s only 152 pages, and she takes some of that to advertise her online services in an effort to upsell the reader.

Nevertheless, there’s a lot of worth in the book itself, and the writing style is certainly easy-reading and compelling.

Bottom line: this book is half instructional, half motivational, and covers some very important areas of health.

Click here to check out “Hard to Kill”, and enjoy robust health at every age!

Share This Post

-

The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work – by Dr. John Gottman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A lot of relationship advice can seem a little wishy-washy. Hardline clinical work, on the other hand, can seem removed from the complex reality of married life. Dr. Gottman, meanwhile, strikes a perfect balance.

He looks at huge datasets, and he listens to very many couples. He famously isolated four relational factors that predict divorce with 91% accuracy, his “Four Horsemen”:

- Criticism

- Contempt

- Defensiveness

- Stonewalling

He also, as the title of this book promises (and we get a chapter-by-chapter deep-dive on each of them) looks at “Seven principles for making marriage work”. They’re not one-word items, so including them here would take up the rest of our space, and this is a book review not a book summary. However…

Dr. Gottman’s seven principles are, much like his more famous “four horsemen”, deeply rooted in science, while also firmly grounded in the reality of individual couples. Essentially, by listening to very many couples talk about their relationships, and seeing how things panned out with each of them in the long-term, he was able to see what things kept on coming up each time in the couples that worked out. What did they do differently?

And, that’s the real meat of the book. Science yes, but lots of real-world case studies and examples, from couples that worked and couples that didn’t.

In so doing, he provides a roadmap for couples who are serious about making their marriage the best it can be.

Bottom line: this is a must-have book for couples in general, no matter how good or bad the relationship.

- For some it’ll be a matter of realising “You know what; this isn’t going to work”

- For others, it’ll be a matter of “Ah, relief, this is how we can resolve that!”

- For still yet others, it’ll be a matter of “We’re doing these things right; let’s keep them forefront in our minds and never get complacent!”

- And for everyone who is in a relationship or thinking of getting into one, it’s a top-tier manual.

Share This Post

-

Blood-Brain Barrier Breach Blamed For Brain-Fog

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Move Over, Leaky Gut. Now It’s A Leaky Brain.

…which is not a headline that promises good news, and indeed, the only good news about this currently is “now we know another thing that’s happening, and thus can work towards a treatment for it”.

Back in February (most popular media outlets did not rush to publish this, as it rather goes against the narrative of “remember when COVID was a thing?” as though the numbers haven’t risen since the state of emergency was declared over), a team of Irish researchers made a discovery:

❝For the first time, we have been able to show that leaky blood vessels in the human brain, in tandem with a hyperactive immune system may be the key drivers of brain fog associated with long covid❞

~ Dr. Matthew Campbell (one of the researchers)

Let’s break that down a little, borrowing some context from the paper itself:

- the leaky blood vessels are breaching the blood-brain-barrier

- that’s a big deal, because that barrier is our only filter between our brain and Things That Definitely Should Not Go In The Brain™

- a hyperactive immune system can also be described as chronic inflammation

- in this case, that includes chronic neuroinflammation which, yes, is also a major driver of dementia

You may be wondering what COVID has to do with this, and well:

- these blood-brain-barrier breaches were very significantly associated (in lay terms: correlated, but correlated is only really used as an absolute in write-ups) with either acute COVID infection, or Long Covid.

- checking this in vitro, exposure of brain endothelial cells to serum from patients with Long Covid induced the same expression of inflammatory markers.

How important is this?

As another researcher (not to mention: professor of neurology and head of the school of medicine at Trinity) put it:

❝The findings will now likely change the landscape of how we understand and treat post-viral neurological conditions.

It also confirms that the neurological symptoms of long covid are measurable with real and demonstrable metabolic and vascular changes in the brain.❞

~ Dr. Colin Doherty (see mini-bio above)

You can read a pop-science article about this here:

Irish researchers discover underlying cause of “brain fog” linked with long covid

…and you can read the paper in full here:

Want to stay safe?

Beyond the obvious “get protected when offered boosters/updates” (see also: The Truth About Vaccines), other good practices include the same things most people were doing when the pandemic was big news, especially avoiding enclosed densely-populated places, washing hands frequently, and looking after your immune system. For that latter, see also:

Beyond Supplements: The Real Immune-Boosters!

Take care!

Share This Post

- the leaky blood vessels are breaching the blood-brain-barrier

Related Posts

-

Keep Inflammation At Bay

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How to Prevent (or Reduce) Inflammation

You asked us to do a main feature on inflammation, so here we go!

Before we start, it’s worth noting an important difference between acute and chronic inflammation:

- Acute inflammation is generally when the body detects some invader, and goes to war against it. This (except in cases such as allergic responses) is usually helpful.

- Chronic inflammation is generally when the body does a civil war. This is almost never helpful.

We’ll be tackling the latter, which frees up your body’s resources to do better at the former.

First, the obvious…

These five things are as important for this as they are for most things:

- Get a good diet—the Mediterranean diet is once again a top-scorer

- Exercise—move and stretch your body; don’t overdo it, but do what you reasonably can, or the inflammation will get worse.

- Reduce (or ideally eliminate) alcohol consumption. When in pain, it’s easy to turn to the bottle, and say “isn’t this one of red wine’s benefits?” (it isn’t, functionally*). Alcohol will cause your inflammation to flare up like little else.

- Don’t smoke—it’s bad for everything, and that goes for inflammation too.

- Get good sleep. Obviously this can be difficult with chronic pain, but do take your sleep seriously. For example, invest in a good mattress, nice bedding, a good bedtime routine, etc.

*Resveratrol (which is a polyphenol, by the way), famously found in red wine, does have anti-inflammatory properties. However, to get enough resveratrol to be of benefit would require drinking far more wine than will be good for your inflammation or, indeed, the rest of you. So if you’d like resveratrol benefits, consider taking it as a supplement. Superficially it doesn’t seem as much fun as drinking red wine, but we assure you that the results will be much more fun than the inflammation flare-up after drinking.

About the Mediterranean Diet for this…

There are many causes of chronic inflammation, but here are some studies done with some of the most common ones:

- Beneficial effect of Mediterranean diet in systemic lupus erythematosus patients

- How the Mediterranean diet and some of its components modulate inflammatory pathways in arthritis

- The effects of the Mediterranean diet on biomarkers of vascular wall inflammation and plaque vulnerability in subjects with high risk for cardiovascular disease

- Adherence to Mediterranean diet and 10-year incidence of diabetes: correlations with inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers*

*Type 1 diabetes is a congenital autoimmune disorder, as the pancreas goes to war with itself. Type 2 diabetes is different, being a) acquired and b) primarily about insulin resistance, and/but this is related to chronic inflammation regardless. It is also possible to have T1D and go on to develop insulin resistance, and that’s very bad, and/but beyond the scope of today’s newsletter, in which we are focusing on the inflammation aspects.

Some specific foods to eat or avoid…

Eat these:

- Leafy greens

- Cruciferous vegetables

- Tomatoes

- Fruits in general (berries in particular)

- Healthy fats, e.g. olives and olive oil

- Almonds and other nuts

- Dark chocolate (choose high cocoa, low sugar)

Avoid these:

- Processed meats (absolute worst offenders are hot dogs, followed by sausages in general)

- Red meats

- Sugar (includes most fruit juices, but not most actual fruits—the difference with actual fruits is they still contain plenty of fiber, and in many cases, antioxidants/polyphenols that reduce inflammation)

- Dairy products (unless fermented, in which case it seems to be at worst neutral, sometimes even a benefit, in moderation)

- White flour (and white flour products, e.g. white bread, white pasta, etc)

- Processed vegetable oils

See also: 9 Best Drinks To Reduce Inflammation, Says Science

Supplements?

Some supplements that have been found to reduce inflammation include:

(links are to studies showing their efficacy)

Consider Intermittent Fasting

Remember when we talked about the difference between acute and chronic inflammation? It’s fair to wonder “if I reduce my inflammatory response, will I be weakening my immune system?”, and the answer is: generally, no.

Often, as with the above supplements and dietary considerations, reducing inflammation actually results in a better immune response when it’s actually needed! This is because your immune system works better when it hasn’t been working in overdrive constantly.

Here’s another good example: intermittent fasting reduces the number of circulating monocytes (a way of measuring inflammation) in healthy humans—but doesn‘t compromise antimicrobial (e.g. against bacteria and viruses) immune response.

See for yourself: Dietary Intake Regulates the Circulating Inflammatory Monocyte Pool ← the study is about the anti-inflammatory effects of fasting

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Vaping: A Lot Of Hot Air?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Vaping: A Lot Of Hot Air?

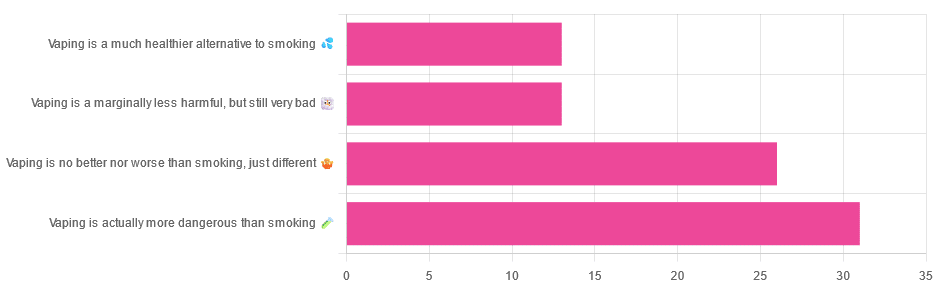

Yesterday, we asked you for your (health-related) opinions on vaping, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- A little over a third of respondents said it’s actually more dangerous than smoking

- A little under a third of respondents said it’s no better nor worse, just different

- A little over 10% of respondents said it’s marginally less harmful, but still very bad

- A little over 10% of respondents said it’s a much healthier alternative to smoking

So what does the science say?

Vaping is basically just steam inhalation, plus the active ingredient of your choice (e.g. nicotine, CBD, THC, etc): True or False?

False! There really are a lot of other chemicals in there.

And “chemicals” per se does not necessarily mean evil green glowing substances that a comicbook villain would market, but there are some unpleasantries in there too:

- Potential harmful health effects of inhaling nicotine-free shisha-pen vapor: a chemical risk assessment of the main components propylene glycol and glycerol

- Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses Induced by Exposure to Commonly Used e-Cigarette Flavoring Chemicals and Flavored e-Liquids without Nicotine

So, the substrate itself can cause irritation, and flavorings (with cinnamaldehyde, the cinnamon flavoring, being one of the worst) can really mess with our body’s inflammatory and oxidative responses.

Vaping can cause “popcorn lung”: True or False?

True and False! Popcorn lung is so-called after it came to attention when workers at a popcorn factory came down with it, due to exposure to diacetyl, a chemical used there.

That chemical was at that time also found in most vapes, but has since been banned in many places, including the US, Canada, the EU and the UK.

Vaping is just as bad as smoking: True or False?

False, per se. In fact, it’s recommended as a means of quitting smoking, by the UK’s famously thrifty NHS, that absolutely does not want people to be sick because that costs money:

Of course, the active ingredients (e.g. nicotine, in the assumed case above) will still be the same, mg for mg, as they are for smoking.

Vaping is causing a health crisis amongst “kids nowadays”: True or False?

True—it just happens to be less serious on a case-by-case basis to the risks of smoking.

However, it is worth noting that the perceived harmlessness of vapes is surely a contributing factor in their widespread use amongst young people—decades after actual smoking (thankfully) went out of fashion.

On the other hand, there’s a flipside to this:

Flavored vape restrictions lead to higher cigarette sales

So, it may indeed be the case of “the lesser of two evils”.

Want to know more?

For a more in-depth science-ful exploration than we have room for here…

BMJ | Impact of vaping on respiratory health

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gut Health for Women – by Aurora Bloom

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First things first: though the title says “For Women”, almost all of it applies to men too—and the things that don’t apply, don’t cause a problem. So if you’re cooking for your family that contains one or more men, this is still great.

Bloom gives us a good, simple, practical introduction to gut health. Her overview also covers gut-related ailments beyond the obvious “tummy hurts”. On which note:

A very valuable section of this book covers dealing with any stomach-upsets that do occur… without harming your trillions of tiny friends (friendly gut microbiota). This alone can make a big difference!

The book does of course also cover the things you’d most expect: things to eat or avoid. But it goes beyond that, looking at optimizing and maintaining your gut health. It’s not just dietary advice here, because the gut affects—and is affected by—other lifestyle factors too. Ranges from mindful eating, to a synchronous sleep schedule, to what kinds of exercise are best to keep your gut ticking over nicely.

There’s also a two-week meal plan, and an extensive appendix of resources, not to mention a lengthy bibliography for sourcing health claims (and suggesting further reading).

In short, a fine and well-written guide to optimizing your gut health and enjoying the benefits.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: