Fennel vs Artichoke – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing fennel to artichoke, we picked the artichoke.

Why?

Both are great! But artichoke wins on nutritional density.

In terms of macros, artichoke has more protein and more fiber, for only slightly more carbs.

Vitamins are another win for artichoke, boasting more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, and choline. Meanwhile, fennel has more of vitamins A, E, and K, which is also very respectable but does allow artichoke a 6:3 lead.

In the category of minerals, artichoke has a lot more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus, while fennel has a little more calcium, potassium, and selenium.

One other relevant factor is that fennel is a moderate appetite suppressant, which may be good or bad depending on your food-related goals.

All in all though, we say the artichoke wins by virtue of its greater abundance of nutrients!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What Matters Most For Your Heart? ← appropriately enough, with fennel hearts and artichoke hearts!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Quinoa vs Couscous – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing quinoa to couscous, we picked the quinoa.

Why?

Firstly, quinoa is the least processed by far. Couscous, even if wholewheat, has by necessity been processed to make what is more or less the same general “stuff” as pasta. Now, the degree to which something has or has not been processed is a common indicator of healthiness, but not necessarily declarative. There are some processed foods that are healthy (e.g. many fermented products) and there are some unprocessed plant or animal products that can kill you (e.g. red meat’s health risks, or the wrong mushrooms). But in this case—quinoa vs couscous—it’s all borne out pretty much as expected.

For the purposes of the following comparisons, we’ll be looking at uncooked/dry weights.

In terms of macros, quinoa has a little more protein, slightly lower carbs, and several times the fiber. The amino acids making up quinoa’s protein are also much more varied.

In the category of vitamins, quinoa has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, and B9, while couscous boasts a little more of vitamins B3 and B5. Given the respective margins of difference, as well as the total vitamins contained, this category is an easy win for quinoa.

When it comes to minerals, this one’s not even more clear. Quinoa has a lot more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Couscous, meanwhile has more of just one mineral: sodium. So, maybe not one you want more of.

All in all, today’s is an easy pick: quinoa!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Carbohydrate Mythbusting: Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

- What’s The Real Deal With The Paleo Diet?

- Gluten Mythbusting: What’s The Truth? ← we didn’t mention it above, but couscous is by default gluten-free, and couscous, being made of wheat, is by default not gluten-free, which may be another reason for some to choose quinoa

Take care!

Share This Post

-

From banning junk food ads to a sugar tax: with diabetes on the rise, we can’t afford to ignore the evidence any longer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are renewed calls this week for the Australian government to implement a range of measures aimed at improving our diets. These include restrictions on junk food advertising, improvements to food labelling, and a levy on sugary drinks.

This time the recommendations come from a parliamentary inquiry into diabetes in Australia. Its final report, tabled in parliament on Wednesday, was prepared by a parliamentary committee comprising members from across the political spectrum.

The release of this report could be an indication that Australia is finally going to implement the evidence-based healthy eating policies public health experts have been recommending for years.

But we know Australian governments have historically been unwilling to introduce policies the powerful food industry opposes. The question is whether the current government will put the health of Australians above the profits of companies selling unhealthy food.

benjamas11/Shutterstock Diabetes in Australia

Diabetes is one of the fastest growing chronic health conditions in the nation, with more than 1.3 million people affected. Projections show the number of Australians diagnosed with the condition is set to rise rapidly in coming decades.

Type 2 diabetes accounts for the vast majority of cases of diabetes. It’s largely preventable, with obesity among the strongest risk factors.

This latest report makes it clear we need an urgent focus on obesity prevention to reduce the burden of diabetes. Type 2 diabetes and obesity cost the Australian economy billions of dollars each year and preventive solutions are highly cost-effective.

This means the money spent on preventing obesity and diabetes would save the government huge amounts in health care costs. Prevention is also essential to avoid our health systems being overwhelmed in the future.

What does the report recommend?

The report puts forward 23 recommendations for addressing diabetes and obesity. These include:

- restrictions on the marketing of unhealthy foods to children, including on TV and online

- improvements to food labelling that would make it easier for people to understand products’ added sugar content

- a levy on sugary drinks, where products with higher sugar content would be taxed at a higher rate (commonly called a sugar tax).

These key recommendations echo those prioritised in a range of reports on obesity prevention over the past decade. There’s compelling evidence they’re likely to work.

Restrictions on unhealthy food marketing

There was universal support from the committee for the government to consider regulating marketing of unhealthy food to children.

Public health groups have consistently called for comprehensive mandatory legislation to protect children from exposure to marketing of unhealthy foods and related brands.

An increasing number of countries, including Chile and the United Kingdom, have legislated unhealthy food marketing restrictions across a range of settings including on TV, online and in supermarkets. There’s evidence comprehensive policies like these are having positive results.

In Australia, the food industry has made voluntary commitments to reduce some unhealthy food ads directly targeting children. But these promises are widely viewed as ineffective.

The government is currently conducting a feasibility study on additional options to limit unhealthy food marketing to children.

But the effectiveness of any new policies will depend on how comprehensive they are. Food companies are likely to rapidly shift their marketing techniques to maximise their impact. If any new government restrictions do not include all marketing channels (such as TV, online and on packaging) and techniques (including both product and brand marketing), they’re likely to fail to adequately protect children.

Food labelling

Food regulatory authorities are currently considering a range of improvements to food labelling in Australia.

For example, food ministers in Australia and New Zealand are soon set to consider mandating the health star rating front-of-pack labelling scheme.

Public health groups have consistently recommended mandatory implementation of health star ratings as a priority for improving Australian diets. Such changes are likely to result in meaningful improvements to the healthiness of what we eat.

Regulators are also reviewing potential changes to how added sugar is labelled on product packages. The recommendation from the committee to include added sugar labelling on the front of product packaging is likely to support this ongoing work.

But changes to food labelling laws are notoriously slow in Australia. And food companies are known to oppose and delay any policy changes that might hurt their profits.

Health star ratings are not compulsory in Australia. BLACKDAY/Shutterstock A sugary drinks tax

Of the report’s 23 recommendations, the sugary drinks levy was the only one that wasn’t universally supported by the committee. The four Liberal and National party members of the committee opposed implementation of this policy.

As part of their rationale, the dissenting members cited submissions from food industry groups that argued against the measure. This follows a long history of the Liberal party siding with the sugary drinks industry to oppose a levy on their products.

The dissenting members didn’t acknowledge the strong evidence that a sugary drinks levy has worked as intended in a wide range of countries.

In the UK, for example, a levy on sugary drinks implemented in 2018 has successfully lowered the sugar content in UK soft drinks and reduced sugar consumption.

The dissenting committee members argued a sugary drinks levy would hurt families on lower incomes. But previous Australian modelling has shown the two most disadvantaged quintiles would reap the greatest health benefits from such a levy, and accrue the highest savings in health-care costs.

What happens now?

Improvements to population diets and prevention of obesity will require a comprehensive and coordinated package of policy reforms.

Globally, a range of countries facing rising epidemics of obesity and diabetes are starting to take such strong preventive action.

In Australia, after years of inaction, this week’s report is the latest sign that long-awaited policy change may be near.

But meaningful and effective policy change will require politicians to listen to the public health evidence rather than the protestations of food companies concerned about their bottom line.

Gary Sacks, Professor of Public Health Policy, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Asparagus vs Eggplant – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing asparagus to eggplant, we picked the asparagus.

Why?

In terms of macros, they’re very similar. Technically asparagus has twice the protein, but it’s at 2.2g/100g compared to eggplant’s 0.98g/100g, so it’s not too meaningful. They’re both mostly water, low in carbs, with a little fiber, and negligible fat (though eggplant technically has more fat, but again, these numbers are miniscule). For practical purposes, the two vegetables are even in this category, or if you really want decisive answers, a tiny margin of a win for asparagus.

In the category of vitamins, asparagus is much higher in vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, E, & K, as well as choline. Eggplant is not higher in any vitamins. A clear win for asparagus.

When it comes to minerals, asparagus is much higher in calcium, copper, iron, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while eggplant is a little higher in manganese. Another easy win for asparagus.

Lastly, asparagus wins on polyphenols too, with its high quercetin content. Eggplant does contain some polyphenols, but in such tiny amounts that even added up they’re less than 7% of what asparagus has to offer in quercetin alone.

Obviously, enjoy both, though! Diversity is healthy.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Fight Inflammation & Protect Your Brain, With Quercetin

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Tourette’s Syndrome Treatment Options

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Is there anything special that might help someone with Tourette’s syndrome?❞

There are of course a lot of different manifestations of Tourette’s syndrome, and some people’s tics may be far more problematic to themselves and/or others, while some may be quite mild and just something to work around.

It’s an interesting topic for sure, so we’ll perhaps do a main feature (probably also covering the related-and-sometimes-overlapping OCD umbrella rather than making it hyperspecific to Tourette’s), but meanwhile, you might consider some of these options:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

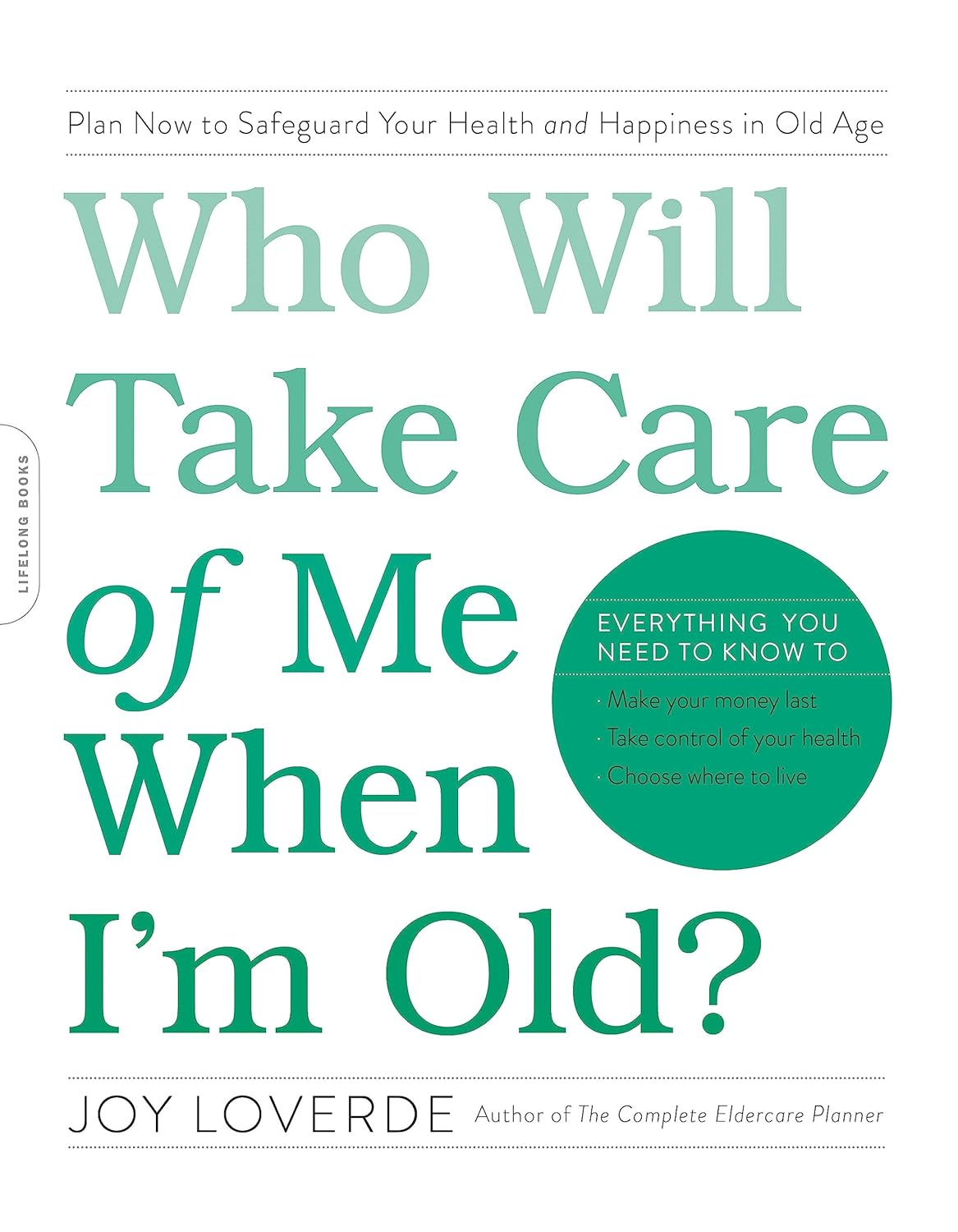

Who Will Take Care of Me When I’m Old? – by Joy Loverde

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Regular readers of 10almonds will know we’ve written before about how isolation kills (in numerous ways), and this book tackles that in much greater length and depth than we ever have room for here.

Specifically, she talks about preparing for medical and related (financial, living will in case of dementia, housing, etc) considerations down the line, with checklists and worksheets and such to make it easy, and help you make sure it actually gets done.

She also talks about creating a support network, from scratch if necessary (“foraging a family”), so that even if you will now be prepared to handle things alone, you’ll become a lot less likely to need to do so.

Unlike many books of this genre, she also covers managing your mortality; that “just shoot me” is not a plan, and what lessons can be learned from the dying to make our own last years the best they can be.

The style is upbeat and positive in outlook; less “prepare for doom” and more “get ready to do things right”, and it’s worth mentioning that the format is particularly helpful, outlining objectives towards the beginning of each chapter, and additional resources at the end of each chapter.

Over on Amazon, most of the reviews that contain any criticism are some manner of “I’m in my 70s and wish I had read this sooner”. Still, better late than never.

Bottom line: if you do not have an overabundance of support network around you, then this is an important book to read and to put into action.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Oscar contender Poor Things is a film about disability. Why won’t more people say so?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Readers are advised this article includes an offensive and outdated disability term in a quote from the film.

Poor Things is a spectacular film that has garnered critical praise, scooped up awards and has 11 Oscar nominations. That might be the problem. Audiences become absorbed in another world, so much so our usual frames of reference disappear.

There has been much discussion about the film’s feminist potential (or betrayal). What’s not being talked about in mainstream reviews is disability. This seems strange when two of the film’s main characters are disabled.

Set in a fantasy version of Victorian London, unorthodox Dr Godwin Baxter (William Dafoe) finds the just-dead body of a heavily pregnant woman in the Thames River. In keeping with his menagerie of hybrid animals, Godwin removes the unborn baby’s brain and puts it into the skull of its mother, who becomes Bella Baxter (Emma Stone).

Is Bella really disabled?

Stone has been praised for her ability to embody a small child who rapidly matures into a hypersexual person – one who has not had time to absorb the restrictive rules of gender or patriarchy.

But we also see a woman using her behaviour to express herself because she has complex communication barriers. We see a woman who is highly sensitive and responsive to the sensory world around her. A woman moving through and seeing the world differently – just like the fish-eye lens used in many scenes.

Women like this exist and they have historically been confined, studied and monitored like Bella. When medical student Max McCandless (Ramy Youssef) first meets Bella, he offensively exclaims “what a very pretty retard!” before being told the truth and promptly declared her future husband.

Even if Bella is not coded as disabled through her movements, speech and behaviour, her onscreen creator and guardian is. Godwin Baxter has facial differences and other impairments which require assistive technology.

So ignoring disability as a theme of the film seems determined and overt. The absurd humour for which the film is being lauded is often at Bella’s “primitive”, “monstrous” or “damaged” actions: words which aren’t usually used to describe children, but have been used to describe disabled people throughout history.

In reviews, Bella’s walk and speech are compared to characters like the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, rather than a disabled woman. So why the resistance?

Freak shows and displays

Disability studies scholar Rosemarie Gardland-Thomson writes “the history of disabled people in the Western world is in part the history of being on display”.

In the 19th century, when Poor Things is set, “freak shows” featuring disabled people, Indigenous people and others with bodily differences were extremely popular.

Doctors used freak shows to find specimens – like Joseph Merrick (also known as the Elephant Man and later depicted on screen) who was used for entertainment before he was exhibited in lecture halls. In the mid-1800s, as medicine became a profession, observing the disabled body shifted from a public spectacle to a private medical gaze that labelled disability as “sick” and pathologised it.

Poor Things doesn’t just circle around these discourses of disability. Bella’s body is a medical experiment, kept locked away for the private viewing of male doctors who take notes about her every move in small pads. While there is something glorious, intimate and familiar about Bella’s discovery of her own sexual pleasure, she immediately recognises it as worth recording in the third person:

I’ve discovered something that I must share […] Bella discover happy when she want!

The film’s narrative arc ends with Bella herself training to be a doctor but one whose more visible disabilities have disappeared.

Framing charity and sexual abuse

Even the film’s title is an expression often used to describe disabled people. The charity model of disability sees disabled people as needing pity and support from others. Financial poverty is briefly shown at a far-off port in the film and Bella initially becomes a sex worker in Paris for money – but her more pressing concern is sexual pleasure.

Disabled women’s sexuality is usually seen as something that needs to be controlled. It is frequently assumed disabled women are either hypersexual or de-gendered and sexually innocent.

In the real world disabled people experience much higher rates of abuse, including sexual assault, than others. Last year’s Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability found women with disability are nearly twice as likely as women without disability to have been assaulted. Almost a third of women with disability have experienced sexual assault by the age of 15. Bella’s hypersexual curiosity appears to give her some layer of protection – but that portrayal denies the lived experience of many.

Watch but don’t ignore

Poor Things is a stunning film. But ignoring disability in the production ignores the ways in which the representation of disabled bodies play into deep and historical stereotypes about disabled people.

These representations continue to shape lives.

Louisa Smith, Senior lecturer, Deakin University; Gemma Digby, Lecturer – Health & Social Development, Deakin University, and Shane Clifton, Associate Professor of Practice, School of Health Sciences and the Centre for Disability Research and Policy, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: