Why Many Nonprofit (Wink, Wink) Hospitals Are Rolling in Money

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One owns a for-profit insurer, a venture capital company, and for-profit hospitals in Italy and Kazakhstan; it has just acquired its fourth for-profit hospital in Ireland. Another owns one of the largest for-profit hospitals in London, is partnering to build a massive training facility for a professional basketball team, and has launched and financed 80 for-profit start-ups. Another partners with a wellness spa where rooms cost $4,000 a night and co-invests with “leading private equity firms.”

Do these sound like charities?

These diversified businesses are, in fact, some of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital systems. And they have somehow managed to keep myriad for-profit enterprises under their nonprofit umbrella — a status that means they pay little or no taxes, float bonds at preferred rates, and gain numerous other financial advantages.

Through legal maneuvering, regulatory neglect, and a large dollop of lobbying, they have remained tax-exempt charities, classified as 501(c)(3)s.

“Hospitals are some of the biggest businesses in the U.S. — nonprofit in name only,” said Martin Gaynor, an economics and public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “They realized they could own for-profit businesses and keep their not-for-profit status. So the parking lot is for-profit; the laundry service is for-profit; they open up for-profit entities in other countries that are expressly for making money. Great work if you can get it.”

Many universities’ most robust income streams come from their technically nonprofit hospitals. At Stanford University, 62% of operating revenue in fiscal 2023 was from health services; at the University of Chicago, patient services brought in 49% of operating revenue in fiscal 2022.

To be sure, many hospitals’ major source of income is still likely to be pricey patient care. Because they are nonprofit and therefore, by definition, can’t show that thing called “profit,” excess earnings are called “operating surpluses.” Meanwhile, some nonprofit hospitals, particularly in rural areas and inner cities, struggle to stay afloat because they depend heavily on lower payments from Medicaid and Medicare and have no alternative income streams.

But investments are making “a bigger and bigger difference” in the bottom line of many big systems, said Ge Bai, a professor of health care accounting at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. Investment income helped Cleveland Clinic overcome the deficit incurred during the pandemic.

When many U.S. hospitals were founded over the past two centuries, mostly by religious groups, they were accorded nonprofit status for doling out free care during an era in which fewer people had insurance and bills were modest. The institutions operated on razor-thin margins. But as more Americans gained insurance and medical treatments became more effective — and more expensive — there was money to be made.

Not-for-profit hospitals merged with one another, pursuing economies of scale, like joint purchasing of linens and surgical supplies. Then, in this century, they also began acquiring parts of the health care systems that had long been for-profit, such as doctors’ groups, as well as imaging and surgery centers. That raised some legal eyebrows — how could a nonprofit simply acquire a for-profit? — but regulators and the IRS let it ride.

And in recent years, partnerships with, and ownership of, profit-making ventures have strayed further and further afield from the purported charitable health care mission in their community.

“When I first encountered it, I was dumbfounded — I said, ‘This not charitable,’” said Michael West, an attorney and senior vice president of the New York Council of Nonprofits. “I’ve long questioned why these institutions get away with it. I just don’t see how it’s compliant with the IRS tax code.” West also pointed out that they don’t act like charities: “I mean, everyone knows someone with an outstanding $15,000 bill they can’t pay.”

Hospitals get their tax breaks for providing “charity care and community benefit.” But how much charity care is enough and, more important, what sort of activities count as “community benefit” and how to value them? IRS guidance released this year remains fuzzy on the issue.

Academics who study the subject have consistently found the value of many hospitals’ good work pales in comparison with the value of their tax breaks. Studies have shown that generally nonprofit and for-profit hospitals spend about the same portion of their expenses on the charity care component.

Here are some things listed as “community benefit” on hospital systems’ 990 tax forms: creating jobs; building energy-efficient facilities; hiring minority- or women-owned contractors; upgrading parks with lighting and comfortable seating; creating healing gardens and spas for patients.

All good works, to be sure, but health care?

What’s more, to justify engaging in for-profit business while maintaining their not-for-profit status, hospitals must connect the business revenue to that mission. Otherwise, they pay an unrelated business income tax.

“Their CEOs — many from the corporate world — spout drivel and turn somersaults to make the case,” said Lawton Burns, a management professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They do a lot of profitable stuff — they’re very clever and entrepreneurial.”

The truth is that a number of not-for-profit hospitals have become wealthy diversified business organizations. The most visible manifestation of that is outsize executive compensation at many of the country’s big health systems. Seven of the 10 most highly paid nonprofit CEOs in the United States run hospitals and are paid millions, sometimes tens of millions, of dollars annually. The CEOs of the Gates and Ford foundations make far less, just a bit over $1 million.

When challenged about the generous pay packages — as they often are — hospitals respond that running a hospital is a complicated business, that pharmaceutical and insurance execs make much more. Also, board compensation committees determine the payout, considering salaries at comparable institutions as well as the hospital’s financial performance.

One obvious reason for the regulatory tolerance is that hospital systems are major employers — the largest in many states (including Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Arizona, and Delaware). They are big-time lobbying forces and major donors in Washington and in state capitals.

But some patients have had enough: In a suit brought by a local school board, a judge last year declared that four Pennsylvania hospitals in the Tower Health system had to pay property taxes because its executive pay was “eye popping” and it demonstrated “profit motives through actions such as charging management fees from its hospitals.”

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report chided the IRS for its lack of vigilance in reviewing nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit and recommended ways to “improve IRS oversight.” A follow-up GAO report to Congress in 2023 said, “IRS officials told us that the agency had not revoked a hospital’s tax-exempt status for failing to provide sufficient community benefits in the previous 10 years” and recommended that Congress lay out more specific standards. The IRS declined to comment for this column.

Attorneys general, who regulate charity at the state level, could also get involved. But, in practice, “there is zero accountability,” West said. “Most nonprofits live in fear of the AG. Not hospitals.”

Today’s big hospital systems do miraculous, lifesaving stuff. But they are not channeling Mother Teresa. Maybe it’s time to end the community benefit charade for those that exploit it, and have these big businesses pay at least some tax. Communities could then use those dollars in ways that directly benefit residents’ health.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Mental Health First-Aid That You’ll Hopefully Never Need

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Take Your Mental Health As Seriously As General Health!

Sometimes, health and productivity means excelling—sometimes, it means avoiding illness and unproductivity. Both are essential, and today we’re going to tackle some ground-up stuff. If you don’t need it right now, great; we suggest to read it for when and if you do. But how likely is it that you will?

- One in four of us are affected by serious mental health issues in any given year.

- One in five of us have suicidal thoughts at some point in our lifetime.

- One in six of us are affected to at least some extent by the most commonly-reported mental health issues, anxiety and depression, in any given week.

…and that’s just what’s reported, of course. These stats are from a UK-based source but can be considered indicative generally. Jokes aside, the UK is not a special case and is not measurably worse for people’s mental health than, say, the US or Canada.

While this is not an inherently cheery topic, we think it’s an important one.

Depression, which we’re going to focus on today, is very very much a killer to both health and productivity, after all.

One of the most commonly-used measures of depression is known by the snappy name of “PHQ9”. It stands for “Patient Health Questionnaire Nine”, and you can take it anonymously online for free (without signing up for anything; it’s right there on the page already):

Take The PHQ9 Test Here! (under 2 minutes, immediate results)

There’s a chance you took that test and your score was, well, depressing. There’s also a chance you’re doing just peachy, or maybe somewhere in between. PHQ9 scores can fluctuate over time (because they focus on the past two weeks, and also rely on self-reports in the moment), so you might want to bookmark it to test again periodically. It can be interesting to track over time.

In the event that you’re struggling (or: in case one day you find yourself struggling, or want to be able to support a loved one who is struggling), some top tips that are useful:

Accept that it’s a medical condition like any other

Which means some important things:

- You/they are not lazy or otherwise being a bad person by being depressed

- You/they will probably get better at some point, especially if help is available

- You/they cannot, however, “just snap out of it”; illness doesn’t work that way

- Medication might help (it also might not)

Do what you can, how you can, when you can

Everyone knows the advice to exercise as a remedy for depression, and indeed, exercise helps many. Unfortunately, it’s not always that easy.

Did you ever see the 80s kids’ movie “The Neverending Story”? There’s a scene in which the young hero Atreyu must traverse the “Swamp of Sadness”, and while he has a magical talisman that protects him, his beloved horse Artax is not so lucky; he slows down, and eventually stops still, sinking slowly into the swamp. Atreyu pulls at him and begs him to keep going, but—despite being many times bigger and stronger than Atreyu, the horse just sinks into the swamp, literally drowning in despair.

See the scene: The Neverending Story movie clip – Artax and the Swamp of Sadness (1984)

Wow, they really don’t make kids’ movies like they used to, do they?

But, depression is very much like that, and advice “exercise to feel less depressed!” falls short of actually being helpful, when one is too depressed to do it.

If you’re in the position of supporting someone who’s depressed, the best tool in your toolbox will be not “here’s why you should do this” (they don’t care; not because they’re an uncaring person by nature, but because they are physiologically impeded from caring about themself at this time), but rather:

“please do this with me”

The reason this has a better chance of working is because the depressed person will in all likelihood be unable to care enough to raise and/or maintain an objection, and while they can’t remember why they should care about themself, they’re more likely to remember that they should care about you, and so will go with your want/need more easily than with their own. It’s not a magic bullet, but it’s worth a shot.

What if I’m the depressed person, though?

Honestly, the same, if there’s someone around you that you do care about; do what you can to look after you, for them, if that means you can find some extra motivation.

But I’m all alone… what now?

Firstly, you don’t have to be alone. There are free services that you can access, for example:

- US: https://nami.org/help

- Canada: https://www.wellnesstogether.ca/en-CA

- UK: https://www.samaritans.org/

…which varyingly offer advice, free phone services, webchats, and the like.

But also, there are ways you can look after yourself a little bit; do the things you’d advise someone else to do, even if you’re sure they won’t work:

- Take a little walk around the block

- Put the lights on when you’re not sleeping

- For that matter, get out of bed when you’re not sleeping. Literally lie on the floor if necessary, but change your location.

- Change your bedding, or at least your clothes

- If changing the bedding is too much, change just the pillowcase

- If changing your clothes is too much, change just one item of clothing

- Drink some water; it won’t magically cure you, but you’ll be in slightly better order

- On the topic of water, splash some on your face, if showering/bathing is too much right now

- Do something creative (that’s not self-harm). You may scoff at the notion of “art therapy” helping, but this is a way to get at least some of the lights on in areas of your brain that are a little dark right now. Worst case scenario is it’ll be a distraction from your problems, so give it a try.

- Find a connection to community—whatever that means to you—even if you don’t feel you can join it right now. Discover that there are people out there who would welcome you if you were able to go join them. Maybe one day you will!

- Hiding from the world? That’s probably not healthy, but while you’re hiding, take the time to read those books (write those books, if you’re so inclined), learn that new language, take up chess, take up baking, whatever. If you can find something that means anything to you, go with that for now, ride that wave. Motivation’s hard to come by during depression and you might let many things slide; you might as well get something out of this period if you can.

If you’re not depressed right now but you know you’re predisposed to such / can slip that way?

Write yourself instructions now. Copy the above list if you like.

Most of all: have a “things to do when I don’t feel like doing anything” list.

If you only take one piece of advice from today’s newsletter, let that one be it!

Share This Post

-

What’s the difference between shyness and social anxiety?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

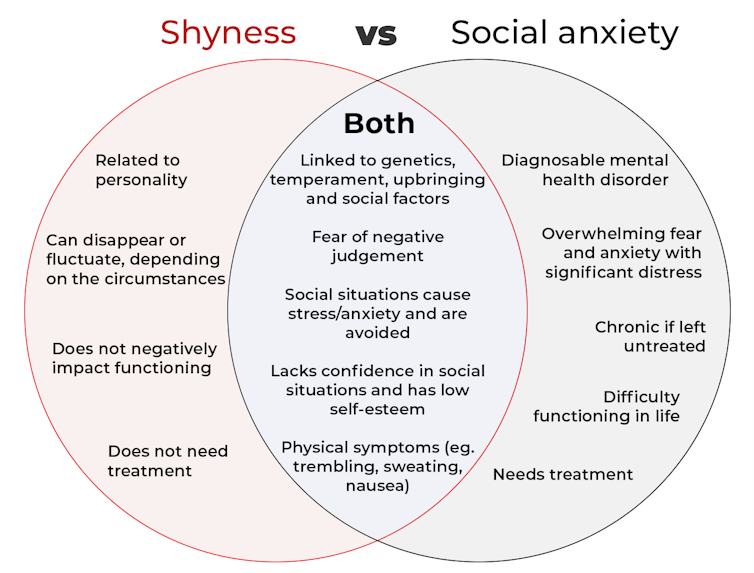

The terms “shyness” and “social anxiety” are often used interchangeably because they both involve feeling uncomfortable in social situations.

However, feeling shy, or having a shy personality, is not the same as experiencing social anxiety (short for “social anxiety disorder”).

Here are some of the similarities and differences, and what the distinction means.

pathdoc/Shutterstock How are they similar?

It can be normal to feel nervous or even stressed in new social situations or when interacting with new people. And everyone differs in how comfortable they feel when interacting with others.

For people who are shy or socially anxious, social situations can be very uncomfortable, stressful or even threatening. There can be a strong desire to avoid these situations.

People who are shy or socially anxious may respond with “flight” (by withdrawing from the situation or avoiding it entirely), “freeze” (by detaching themselves or feeling disconnected from their body), or “fawn” (by trying to appease or placate others).

A complex interaction of biological and environmental factors is also thought to influence the development of shyness and social anxiety.

For example, both shy children and adults with social anxiety have neural circuits that respond strongly to stressful social situations, such as being excluded or left out.

People who are shy or socially anxious commonly report physical symptoms of stress in certain situations, or even when anticipating them. These include sweating, blushing, trembling, an increased heart rate or hyperventilation.

How are they different?

Social anxiety is a diagnosable mental health condition and is an example of an anxiety disorder.

For people who struggle with social anxiety, social situations – including social interactions, being observed and performing in front of others – trigger intense fear or anxiety about being judged, criticised or rejected.

To be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, social anxiety needs to be persistent (lasting more than six months) and have a significant negative impact on important areas of life such as work, school, relationships, and identity or sense of self.

Many adults with social anxiety report feeling shy, timid and lacking in confidence when they were a child. However, not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. Also, feeling shy does not necessarily mean a person meets the criteria for social anxiety disorder.

People vary in how shy or outgoing they are, depending on where they are, who they are with and how comfortable they feel in the situation. This is particularly true for children, who sometimes appear reserved and shy with strangers and peers, and outgoing with known and trusted adults.

Individual differences in temperament, personality traits, early childhood experiences, family upbringing and environment, and parenting style, can also influence the extent to which people feel shy across social situations.

Not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. 249 Anurak/Shutterstock However, people with social anxiety have overwhelming fears about embarrassing themselves or being negatively judged by others; they experience these fears consistently and across multiple social situations.

The intensity of this fear or anxiety often leads people to avoid situations. If avoiding a situation is not possible, they may engage in safety behaviours, such as looking at their phone, wearing sunglasses or rehearsing conversation topics.

The effect social anxiety can have on a person’s life can be far-reaching. It may include low self-esteem, breakdown of friendships or romantic relationships, difficulties pursuing and progressing in a career, and dropping out of study.

The impact this has on a person’s ability to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life, and the distress this causes, differentiates social anxiety from shyness.

Children can show similar signs or symptoms of social anxiety to adults. But they may also feel upset and teary, irritable, have temper tantrums, cling to their parents, or refuse to speak in certain situations.

If left untreated, social anxiety can set children and young people up for a future of missed opportunities, so early intervention is key. With professional and parental support, patience and guidance, children can be taught strategies to overcome social anxiety.

Why does the distinction matter?

Social anxiety disorder is a mental health condition that persists for people who do not receive adequate support or treatment.

Without treatment, it can lead to difficulties in education and at work, and in developing meaningful relationships.

Receiving a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder can be validating for some people as it recognises the level of distress and that its impact is more intense than shyness.

A diagnosis can also be an important first step in accessing appropriate, evidence-based treatment.

Different people have different support needs. However, clinical practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioural therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that teaches people practical coping skills). This is often used with exposure therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that helps people face their fears by breaking them down into a series of step-by-step activities). This combination is effective in-person, online and in brief treatments.

Treatment is available online as well as in-person. ImYanis/Shutterstock For more support or further reading

Online resources about social anxiety include:

- This Way Up’s online program for managing excessive shyness and fear of social situations

- Beyond Blue’s resources on social anxiety

- a guide to looking after yourself if you have social anxiety, from the Western Australian health department

- social anxiety online program for children and teens from the University of Queensland

- inroads, a self-guided online program for young adults who drink alcohol to manage their anxiety.

We thank the Black Dog Institute Lived Experience Advisory Network members for providing feedback and input for this article and our research.

Kayla Steele, Postdoctoral research fellow and clinical psychologist, UNSW Sydney and Jill Newby, Professor, NHMRC Emerging Leader & Clinical Psychologist, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

7 Kinds Of Rest When Sleep Is Not Enough

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Taking Rest Seriously (More Than Just Sleep)

This is Dr. Matthew Edlund. He has 44 years experience as a psychiatrist, and is also a sleep specialist. He has a holistic view of health, which is reflected in his practice; he advocates for “a more complete health: physical, mental, social, and spiritual well-being”.

What does he want us to know?

Sleep, yes

Sleep cannot do all things for us in terms of rest, but it can do a lot, and it is critical. It is, in short, a necessary-but-not-sufficient condition for being well-rested.

See also: Why You Probably Need More Sleep

Rest actively

Rest is generally thought of as a passive activity, if you’ll pardon the oxymoron. Popular thinking is that it’s not something defined by what we do, so much what we stop doing.

In contrast, Dr. Edlund argues that to take rest seriously, we need do restful things.

Rest is as important as eating, and we wouldn’t want for that to “just happen”, would we?

Dr. Edlund advocates for restful activities such as going to the garden (or a nearby park) to relax. He also suggests we not underestimate the power of sex as an actively restful activity—this one is generally safer in the privacy of one’s home, though!

Rest physically

This is about actively relaxing our body—yoga is a great option here, practised in a way that is not physically taxing, but is physically rejuvenating; gentle stretches are key. Without such things, our body will keep tension, and that is not restful.

For the absolute most restful yogic practice? Check out:

Non-Sleep Deep Rest: A Neurobiologist’s Take

this is about yoga nidra!

Rest mentally

The flipside of the above is that we do need to rest our mind also. When we try to rest from a mental activity by taking on a different mental activity that uses the same faculties of the brain, it is not restful.

Writer’s example: as a writer, I could not rest from my writing by writing recreationally, or even by reading. An accountant, however, could absolutely rest from accounting by picking up a good book, should they feel so inclined.

Rest socially

While we all have our preferences when it comes to how much or how little social interaction we like in our lives, humans are fundamentally social creatures, and it is hardwired into us by evolution to function at our best in a community.

This doesn’t mean you have to go out partying every night, but it does mean you should take care to spend at least a little time with friends, even if just once or twice per week, and yes, even if it’s just a videocall (in person is best, but not everyone lives close by!)

If your social life is feeling a little thin on the ground these days, that’s a very common thing—not only as we get older, but also as many social institutions took a dive in functionality on account of the pandemic, and many are still floundering. Nevertheless, there are more options than you probably realize; yes, even for the naturally reclusive:

How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

Rest spiritually

Be we religious or not, there are scientifically well-evidenced benefits to religious practices—some are because of the social aspect, and follow on from what we talked about just above. Other benefits come from activities such as prayer or meditation (which means that having some kind of faith, while beneficial, is not actually a requirement for spiritual rest—comparable practices without faith are fine too).

We discussed the overlapping practices of prayer and meditation, here:

The Science Of Mantra Meditation

Rest at home

Obviously, most people sleep at home. But…

Busy family homes can sometimes need a bit of conscious effort to create a restful environment, even if just for a while. A family dinner together is one great way to achieve this, and also ties in with the social element we mentioned before!

A different challenge faced by a lot of older people without live-in families, on the other hand, is the feeling of too much opportunity for rest—and then a feeling of shame for taking it. The view is commonly held that, for example, taking an afternoon nap is a sign of weakness.

On the contrary: taking an afternoon nap can be a good source of strength! Check out:

How To Nap Like A Pro (No More “Sleep Hangovers”!)

Rest at work

Our readership has a lot of retirees, but we know that’s not the case for everyone. How then, to rest while at work? Ideally we have breaks, of course, but most workplaces do not exactly have an amusement arcade in the break room. Nevertheless, there are some quick resets that can be done easily, anywhere, and (almost) any time:

Meditation Games: Meditation That You’ll Actually Enjoy

Want to know more?

You might also like:

How To Rest More Efficiently (Yes, Really)

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Think Again – by Adam Grant

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Warning: this book may cause some feelings of self-doubt! Ride them out and see where they go, though.

It was Socrates who famously (allegedly) said “ἓν οἶδα ὅτι οὐδὲν οἶδα”—”I know that I know nothing”.

Adam Grant wants us to take this philosophy and apply it usefully to modern life. How?

The main premise is that rethinking our plans, answers and decisions is a good thing… Not a weakness. In contrast, he says, a fixed mindset closes us to opportunities—and better alternatives.

He wants us to be sure that we don’t fall into the trap of the Dunning-Kruger Effect (overestimating our abilities because of being unaware of how little we know), but he also wants us to rethink whole strategies, too. For example:

Grant’s approach to interpersonal conflict is very remniscent of another book we might review sometime, “Aikido in Everyday Life“. The idea here is to not give in to our knee-jerk responses to simply retaliate in kind, but rather to sidestep, pivot, redirect. This is, admittedly, the kind of “rethinking” that one usually has to rethink in advance—it’s too late in the moment! Hence the value of a book.

Nor is the book unduly subjective. “Wishy-washiness” has a bad rep, but Grant gives us plenty in the way of data and examples of how we can, for example, avoid losses by not doubling down on a mistake.

What, then, of strongly-held core principles? Rethinking doesn’t mean we must change our mind—it simply means being open to the possibility in contexts where such makes sense.

Grant borrows, in effect, from:

❝Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better… do better!❞

So, not so much undercutting the principles we hold dear, and instead rather making sure they stand on firm foundations.

All in all, a thought-provokingly inspiring read!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Traveling To Die: The Latest Form of Medical Tourism

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In the 18 months after Francine Milano was diagnosed with a recurrence of the ovarian cancer she thought she’d beaten 20 years ago, she traveled twice from her home in Pennsylvania to Vermont. She went not to ski, hike, or leaf-peep, but to arrange to die.

“I really wanted to take control over how I left this world,” said the 61-year-old who lives in Lancaster. “I decided that this was an option for me.”

Dying with medical assistance wasn’t an option when Milano learned in early 2023 that her disease was incurable. At that point, she would have had to travel to Switzerland — or live in the District of Columbia or one of the 10 states where medical aid in dying was legal.

But Vermont lifted its residency requirement in May 2023, followed by Oregon two months later. (Montana effectively allows aid in dying through a 2009 court decision, but that ruling doesn’t spell out rules around residency. And though New York and California recently considered legislation that would allow out-of-staters to secure aid in dying, neither provision passed.)

Despite the limited options and the challenges — such as finding doctors in a new state, figuring out where to die, and traveling when too sick to walk to the next room, let alone climb into a car — dozens have made the trek to the two states that have opened their doors to terminally ill nonresidents seeking aid in dying.

At least 26 people have traveled to Vermont to die, representing nearly 25% of the reported assisted deaths in the state from May 2023 through this June, according to the Vermont Department of Health. In Oregon, 23 out-of-state residents died using medical assistance in 2023, just over 6% of the state total, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Oncologist Charles Blanke, whose clinic in Portland is devoted to end-of-life care, said he thinks that Oregon’s total is likely an undercount and he expects the numbers to grow. Over the past year, he said, he’s seen two to four out-of-state patients a week — about one-quarter of his practice — and fielded calls from across the U.S., including New York, the Carolinas, Florida, and “tons from Texas.” But just because patients are willing to travel doesn’t mean it’s easy or that they get their desired outcome.

“The law is pretty strict about what has to be done,” Blanke said.

As in other states that allow what some call physician-assisted death or assisted suicide, Oregon and Vermont require patients to be assessed by two doctors. Patients must have less than six months to live, be mentally and cognitively sound, and be physically able to ingest the drugs to end their lives. Charts and records must be reviewed in the state; neglecting to do so constitutes practicing medicine out of state, which violates medical licensing requirements. For the same reason, the patients must be in the state for the initial exam, when they request the drugs, and when they ingest them.

State legislatures impose those restrictions as safeguards — to balance the rights of patients seeking aid in dying with a legislative imperative not to pass laws that are harmful to anyone, said Peg Sandeen, CEO of the group Death With Dignity. Like many aid-in-dying advocates, however, she said such rules create undue burdens for people who are already suffering.

Diana Barnard, a Vermont palliative care physician, said some patients cannot even come for their appointments. “They end up being sick or not feeling like traveling, so there’s rescheduling involved,” she said. “It’s asking people to use a significant part of their energy to come here when they really deserve to have the option closer to home.”

Those opposed to aid in dying include religious groups that say taking a life is immoral, and medical practitioners who argue their job is to make people more comfortable at the end of life, not to end the life itself.

Anthropologist Anita Hannig, who interviewed dozens of terminally ill patients while researching her 2022 book, “The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Assisted Dying in America,” said she doesn’t expect federal legislation to settle the issue anytime soon. As the Supreme Court did with abortion in 2022, it ruled assisted dying to be a states’ rights issue in 1997.

During the 2023-24 legislative sessions, 19 states (including Milano’s home state of Pennsylvania) considered aid-in-dying legislation, according to the advocacy group Compassion & Choices. Delaware was the sole state to pass it, but the governor has yet to act on it.

Sandeen said that many states initially pass restrictive laws — requiring 21-day wait times and psychiatric evaluations, for instance — only to eventually repeal provisions that prove unduly onerous. That makes her optimistic that more states will eventually follow Vermont and Oregon, she said.

Milano would have preferred to travel to neighboring New Jersey, where aid in dying has been legal since 2019, but its residency requirement made that a nonstarter. And though Oregon has more providers than the largely rural state of Vermont, Milano opted for the nine-hour car ride to Burlington because it was less physically and financially draining than a cross-country trip.

The logistics were key because Milano knew she’d have to return. When she traveled to Vermont in May 2023 with her husband and her brother, she wasn’t near death. She figured that the next time she was in Vermont, it would be to request the medication. Then she’d have to wait 15 days to receive it.

The waiting period is standard to ensure that a person has what Barnard calls “thoughtful time to contemplate the decision,” although she said most have done that long before. Some states have shortened the period or, like Oregon, have a waiver option.

That waiting period can be hard on patients, on top of being away from their health care team, home, and family. Blanke said he has seen as many as 25 relatives attend the death of an Oregon resident, but out-of-staters usually bring only one person. And while finding a place to die can be a problem for Oregonians who are in care homes or hospitals that prohibit aid in dying, it’s especially challenging for nonresidents.

When Oregon lifted its residency requirement, Blanke advertised on Craigslist and used the results to compile a list of short-term accommodations, including Airbnbs, willing to allow patients to die there. Nonprofits in states with aid-in-dying laws also maintain such lists, Sandeen said.

Milano hasn’t gotten to the point where she needs to find a place to take the meds and end her life. In fact, because she had a relatively healthy year after her first trip to Vermont, she let her six-month approval period lapse.

In June, though, she headed back to open another six-month window. This time, she went with a girlfriend who has a camper van. They drove six hours to cross the state border, stopping at a playground and gift shop before sitting in a parking lot where Milano had a Zoom appointment with her doctors rather than driving three more hours to Burlington to meet in person.

“I don’t know if they do GPS tracking or IP address kind of stuff, but I would have been afraid not to be honest,” she said.

That’s not all that scares her. She worries she’ll be too sick to return to Vermont when she is ready to die. And, even if she can get there, she wonders whether she’ll have the courage to take the medication. About one-third of people approved for assisted death don’t follow through, Blanke said. For them, it’s often enough to know they have the meds — the control — to end their lives when they want.

Milano said she is grateful she has that power now while she’s still healthy enough to travel and enjoy life. “I just wish more people had the option,” she said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Eating Disorders: More Varied (And Prevalent) Than People Think

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Disordered Eating Beyond The Stereotypes

Around 10% of Americans* have (or have had) an eating disorder. That might not seem like a high percentage, but that’s one in ten; do you know 10 people? If so, it might be a topic that’s near to you.

*Source: Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States of Americ

Our hope is that even if you yourself have never had such a problem in your life, today’s article will help arm you with knowledge. You never know who in your life might need your support.

Very misunderstood

Eating disorders are so widely misunderstood in so many ways that we nearly made this a Friday Mythbusting edition—but we preface those with a poll that we hope to be at least somewhat polarizing or provide a spectrum of belief. In this case, meanwhile, there’s a whole cluster of myths that cannot be summed up in one question. So, here we are doing a Psychology Sunday edition instead.

“Eating disorders aren’t that important”

Eating disorders are the second most deadly category of mental illness, second only to opioid addiction.

Anorexia specifically has the highest case mortality rate of any mental illness:

Source: National Association of Anorexia Nervosa & Associated Disorders: Eating Disorder Statistics

So please, if someone needs help with an eating disorder (including if it’s you), help them.

“Eating disorders are for angsty rebellious teens”

While there’s often an element of “this is the one thing I can control” to some eating disorders (including anorexia and bulimia), eating disorders very often present in early middle-age, very often amongst busy career-driven individuals using it as a coping mechanism to have a feeling of control in their hectic lives.

13% of women over 50 report current core eating disorder symptoms, and that is probably underreported.

Source: as above; scroll to near the bottom!

“Eating disorders are a female thing”

Nope. Officially, men represent around 25% of people diagnosed with eating disorders, but women are 5x more likely to get diagnosed, so you can do the math there. Women are also 1.5% more likely to receive treatment for it.

By the time men do get diagnosed, they’ve often done a lot more damage to their bodies because they, as well as other people, have overlooked the possibility of their eating being disordered, due to the stereotype of it being a female thing.

Source: as above again!

“Eating disorders are about body image”

They can be, but that’s far from the only kind!

Some can be about control of diet, not just for the sake of controlling one’s body, but purely for the sake of controlling the diet itself.

Still yet others can be not about body image or control, like “Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder”, which in lay terms sometimes gets dismissed as “being a picky eater” or simply “losing one’s appetite”, but can be serious.

For example, a common presentation of the latter might be a person who is racked with guilt and/or anxiety, and simply stops eating, because either they don’t feel they deserve it, or “how can I eat at a time like this, when…?” but the time is an ongoing thing so their impromptu fast is too.

Still yet even more others might be about trying to regulate emotions by (in essence) self-medicating with food—not in the healthy “so eat some fruit and veg and nuts etc” sense, but in the “Binge-Eating Disorder” sense.

And that latter accounts for a lot of adults.

You can read more about these things here:

Psychology Today | Types of Eating Disorder ← it’s pop-science, but it’s a good overview

Take care! And if you have, or think you might have, an eating disorder, know that there are organizations that can and will offer help/support in a non-judgmental fashion. Here’s the ANAD’s eating disorder help resource page, for example.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: