CLA for Weight Loss?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Conjugated Linoleic Acid for Weight Loss?

You asked us to evaluate the use of CLA for weight loss, so that’s today’s main feature!

First, what is CLA?

Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) is a fatty acid made by grazing animals. Humans don’t make it ourselves, and it’s not an essential nutrient.

Nevertheless, it’s a popular supplement, mostly sold as a fat-burning helper, and thus enjoyed by slimmers and bodybuilders alike.

❝CLA reduces bodyfat❞—True or False?

True! Contingently. Specifically, it will definitely clearly help in some cases. For example:

- This study found it doubled fat loss in chickens

- It significantly increased delipidation of white adipose tissue in these mice

- The mice in this study enjoyed a 43–88% reduction in (fatty) weight gain

- Over the course of a six-week weight-loss program, these mice got 70% more weight loss on CLA, compared to placebo

- In this study, pigs that took CLA on a high-calorie diet gained 50% less weight than those not taking CLA

- On a heart-unhealthy diet, these hamsters taking CLA gained much less white adipose tissue than their comrades not taking CLA

- Another study with pigs found that again, CLA supplementation resulted in much less weight gained

- These hamsters being fed a high-cholesterol diet found that those taking CLA ended up with a leaner body mass than those not taking CLA

- This study with mice found that CLA supplementation promoted fat loss and lean muscle gain

Did you notice a theme? It’s Animal Farm out there!

❝CLA reduces bodyfat in humans❞—True or False?

False—practically. Technically it appears to give non-significantly better results than placebo.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 18 different studies (in which CLA was provided to humans in randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials and in which body composition was assessed by using a validated technique) found that, on average, human CLA-takers lost…

Drumroll please…

00.00–00.05 kg per week. That’s between 0–50g per week. That’s less than two ounces. Put it this way: if you were to quickly drink an espresso before stepping on the scale, the weight of your very tiny coffee would cover your fat loss.

The reviewers concluded:

❝CLA produces a modest loss in body fat in humans❞

Modest indeed!

See for yourself: Efficacy of conjugated linoleic acid for reducing fat mass: a meta-analysis in humans

But what about long-term? Well, as it happens (and as did show up in the non-human animal studies too, by the way) CLA works best for the first four weeks or so, and then effects taper off.

Another review of longer-term randomized clinical trials (in humans) found that over the course of a year, CLA-takers enjoyed on average a 1.33kg total weight loss benefit over placebo—so that’s the equivalent of about 25g (0.8 oz) per week. We’re talking less than a shot glass now.

They concluded:

❝The evidence from RCTs does not convincingly show that CLA intake generates any clinically relevant effects on body composition on the long term❞

A couple of other studies we’ll quickly mention before closing this section:

- CLA supplementation does not affect waist circumference in humans (at all).

- Amongst obese women doing aerobic exercise, CLA supplementation has no effect (at all) on body fat reduction compared to placebo

What does work?

You may remember this headline from our “What’s happening in the health world” section a few days ago:

Research reveals self-monitoring behaviors and tracking tools key to long-term weight loss success

On which note, we’ve mentioned before, we’ll mention again, and maybe one of these days we’ll do a main feature on it, there’s a psychology-based app/service “Noom” that’s very personalizable and helps you reach your own health goals, whatever they might be, in a manner consistent with any lifestyle considerations you might want to give it.

Curious to give it a go? Check it out at Noom.com (you can get the app there too, if you want)

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Good to Go – by Christie Aschwanden

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many of us may more often need to recover from a day of moving furniture than running a marathon, but the science of recovery can still teach us a lot. The author, herself an endurance athlete and much-decorated science journalist, sets out to do just that.

She explores a lot of recovery methods, and examines whether the science actually backs them up, and if so, to what degree. She also, in true science journalism style, talks to a lot of professionals ranging from fellow athletes to fellow scientists, to get their input too—she is nothing if not thorough, and this is certainly not a book of one person’s opinion with something to sell.

Indeed, on the contrary, her findings show that some of the best recovery methods are the cheapest, or even free. She also looks at the psychological aspect though, and why many people are likely to continue with things that objectively do not work better than placebo.

The style is very easy-reading jargon-free pop-science, while nevertheless being backed up with hundreds of studies cited in the bibliography—a perfect balance of readability and reliability.

Bottom line: for those who wish to be better informed about how to recover quickly and easily, this book is a treasure trove of information well-presented.

Click here to check out Good To Go, and always be good to go!

Share This Post

-

Finding Peace at the End of Life – by Henry Fersko-Weiss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is not the most cheery book we’ve reviewed, but it is an important one. From its first chapter, with “a tale of two deaths”, one that went as well as can be reasonably expected, and the other one not so much, it presents a lot of choices.

The book is not prescriptive in its advice regarding how to deal with these choices, but rather, investigative. It’s thought-provoking, and asks questions—tacitly and overtly.

While the subtitle says “for families and caregivers”, it’s as much worth when it comes to managing one’s own mortality, too, by the way.

As for the scope of the book, it covers everything from terminal diagnosis, through the last part of life, to the death itself, to all that goes on shortly afterwards.

Stylewise, it’s… We’d call it “easy-reading” for style, but obviously the content is very heavy, so you might want to read it a bit at a time anyway, depending on how sensitive to such topics you are.

Bottom line: this book is not exactly a fun read, but it’s a very worthwhile one, and a good way to avoid regrets later.

Share This Post

-

Overcoming Gravity – by Steven Low

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The author, a professional gymnast and coach with a background in the sciences, knows his stuff here. This is what it says on the tin: it’s rigorously systematic. It’s also the most science-based calisthenics book this reviewer has read to date.

If you just wanted to know how to do some exercises, then this book would be very much overkill, but if you want to be able to go from no knowledge to expert knowledge, then the nearly 600 pages of this weighty tome will do that for you.

This is a textbook, it’s a “the bible of…” style book, it’s the one that if you’re serious, will engage you thoroughly and enable you to craft the calisthenics-forged body you want, head to toe.

As if it weren’t already overdelivering, it also has plenty of information on injury avoidance (or injury/condition management if you have some existing injury or chronic condition), and building routines in a dynamic fashion that avoids becoming a grind, because it’s going from strength to strength while cycling through different body parts.

Bottom line: if you’d like to get serious about calisthenics, then this is the book for you.

Click here to check out Overcoming Gravity, and do just that!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Sugary Food That Lowers Blood Sugars

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Loved the article on goji berries! I read they are good for blood sugars, is that true despite the sugar content?❞

Most berries are! Fruits that are high in polyphenols (even if they’re high in sugar), like berries, have a considerable net positive impact on glycemic health:

- Polyphenols and Glycemic Control

- Polyphenols and their effects on diabetes management: A review

- Dietary polyphenols as antidiabetic agents: Advances and opportunities

And more specifically:

Dietary berries, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: an overview of human feeding trials

Read more: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

As for goji berries specifically, they’re very high indeed in polyphenols, and also have a hypoglycemic effect, i.e., they lower blood sugar levels (and as a bonus, increases HDL (“good” cholesterol) levels too, but that’s not the topic here):

❝The results of our study indicated a remarkable protective effect of LBP in patients with type 2 diabetes. Serum glucose was found to be significantly decreased and insulinogenic index increased during OMTT after 3 months administration of LBP. LBP also increased HDL levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. It showed more obvious hypoglycemic efficacy for those people who did not take any hypoglycemic medicine compared to patients taking hypoglycemic medicines. This study showed LBP to be a good potential treatment aided-agent for type 2 diabetes.❞

- LBP = Lycium barbarum polysaccharide, i.e. polysaccharide in/from goji berries

- OMTT = Oral metabolic tolerance test, a test of how well the blood sugars avoid spiking after a meal

For more about goji berries (and also where to get them), for reference our previous article is at:

Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gut Health 101

We have so many microorganisms inside us, that by cell count, their cells outnumber ours more than ten-to-one. By gene count, we have 23,000 and they have more than 3,000,000. In effect, we are more microbe than we are human. And, importantly: they form a critical part of what keeps our overall organism ticking on.

Read all about it: The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health

Our trillions of tiny friends keep us alive, so it really really pays to return the favor.

But how?

Probiotics and fermented foods

You probably guessed this one, but it’d be remiss not to mention it first. It’s no surprise that probiotics help; the clue is in the name. In short, they help add diversity to your microbiome (that’s a good thing).

Read from the NIH: Probiotics: What You Need To Know

As for fermented foods, not every fermented food will boost your microbiota, but great options include…

- Fermented vegetables (sauerkraut, pickles, etc)

- You’ll often hear kimchi mentioned; that is also pickled vegetables, usually mostly cabbage. It’s just the culinary experience that differs. Unlike sauerkraut, kimchi is usually spiced, for example.

- Kombucha (a fermented sweet tea)

- Miso & tempeh (different preparations of fermented soy)

The health benefits vary based on the individual strains of bacteria involved in the fermentation, so don’t get too caught up on which is best.

The best one is the one you enjoy, because then you’ll have it regularly!

Feed them plenty of prebiotic fibers

Those probiotics you took? The bacteria in them eat the fiber that you can’t digest without them. So, feed them those sorts of fibers.

Great options include:

- Bananas

- Garlic

- Onions

- Whole grains

Read more: Effects of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics on Human Health

Don’t feed them sugar and sweeteners

Sugar and (and, counterintuitively, aspartame) can cause unfortunate gut microbe imbalances. Put simply, they kill some of your friends and feed some of your enemies. For example…

Candida, which we all have in us to some degree, feeds on sugar (including the sugar formed from breaking down alcohol, by the way) and refined carbs. Then it grows, and puts its roots through your intestinal walls, linking with your neural system. Then it makes you crave the very things that will feed it and allow it to put bigger holes in your intestinal walls.

Do not feed the Candida.

Don’t believe us? Read: Candida albicans-Induced Epithelial Damage Mediates Translocation through Intestinal Barriers

(That’s scientist-speak for “Candida puts holes in your intestines, and stuff can then go through those holes”)

And as for how that comes about, it’s like we said:

❝Colonization of the intestine and translocation through the intestinal barrier are fundamental aspects of the processes preceding life-threatening systemic candidiasis. In this review, we discuss the commensal lifestyle of C. albicans in the intestine, the role of morphology for commensalism, the influence of diet, and the interactions with bacteria of the microbiota.❞

Source: Candida albicans as a commensal and opportunistic pathogen in the intestine

The usual five things

- Good diet (Mediterranean Diet is good; plant-based version of it is by far the best for this)

- Good exercise (yes, really)

- Good sleep (helps them, and they’ll help you get better sleep in return)

- Limit or eliminate alcohol consumption (what a shocker)

- Don’t smoke (it’s bad for everything, including gut health)

One last thing you should know:

If you’re used to having animal products in your diet, and make a sudden change to all plants, your gut will object very strongly. This is because your gut microbiome is used to animal products, and a plant-based diet will cause many helpful microbes to flourish in great abundance, and many less helpful microbes will starve and die. And they will make it officially Not Fun™ for you.

So, you have two options to consider:

- Do it anyway, and sit it out (and believe us, you’ll be sitting), get the change over with quickly, and enjoy the benefits and much happier gut that follows.

- Make the change gradual. Reduce portions of animal products slowly, have “Meatless Mondays” etc, and slowly make the change over. This—for most people—is pretty comfortable, easy, and effective.

And remember: the effects of these things we’ve talked about today compound when you do more than one of them, but if you don’t want to take probiotics or really hate kombucha or absolutely won’t consider a plant-based diet or struggle to give up sugar or alcohol, etc… Just do what you can do, and you’ll still have a net improvement!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

- Fermented vegetables (sauerkraut, pickles, etc)

-

Migraine Mythbusting

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Migraine: When Headaches Are The Tip Of The Neurological Iceberg

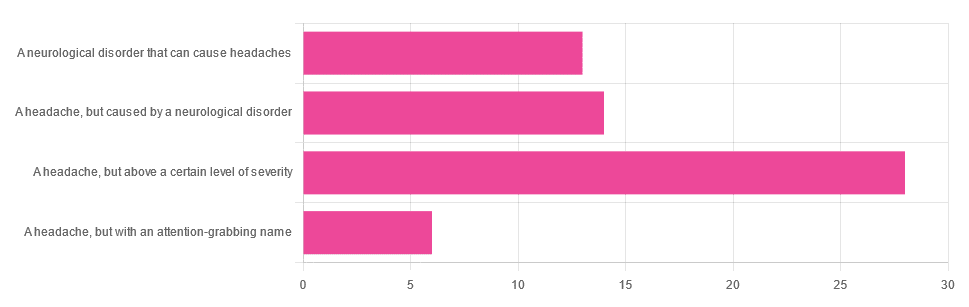

Yesterday, we asked you “What is a migraine?” and got the above-depicted, below-described spread of responses:

- Just under 46% said “a headache, but above a certain level of severity”

- Just under 23% said “a headache, but caused by a neurological disorder”

- Just over 21% said “a neurological disorder that can cause headaches”

- Just under 10% said “a headache, but with an attention-grabbing name”

So… What does the science say?

A migraine is a headache, but above a certain level of severity: True or False?

While that’s usually a very noticeable part of it… That’s only one part of it, and not a required diagnostic criterion. So, in terms of defining what a migraine is, False.

Indeed, migraine may occur without any headache, let alone a severe one, for example: Abdominal Migraine—though this is much less well-researched than the more common with-headache varieties.

Here are the defining characteristics of a migraine, with the handy mnemonic 5-4-3-2-1:

- 5 or more attacks

- 4 hours to 3 days in duration

- 2 or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affects only one side of the head)

- Pulsating

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Worsened by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

- 1 or more of the following:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to both light and sound

Source: Cephalalgia | ICHD-II Classification: Parts 1–3: Primary, Secondary and Other

As one of our subscribers wrote:

❝I have chronic migraine, and it is NOT fun. It takes away from my enjoyment of family activities, time with friends, and even enjoying alone time. Anyone who says a migraine is just a bad headache has not had to deal with vertigo, nausea, loss of balance, photophobia, light sensitivity, or a host of other symptoms.❞

Migraine is a neurological disorder: True or False?

True! While the underlying causes aren’t known, what is known is that there are genetic and neurological factors at play.

❝Migraine is a recurrent, disabling neurological disorder. The World Health Organization ranks migraine as the most prevalent, disabling, long-term neurological condition when taking into account years lost due to disability.

Considerable progress has been made in elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine, associated genetic factors that may influence susceptibility to the disease❞

Source: JHP | Mechanisms of migraine as a chronic evolutive condition

Migraine is just a headache with a more attention-grabbing name: True or False?

Clearly, False.

As we’ve already covered why above, we’ll just close today with a nod to an old joke amongst people with chronic illnesses in general:

“Are you just saying that because you want attention?”

“Yes… Medical attention!”

Want to learn more?

You can find a lot of resources at…

NIH | National Institute of Neurological Disorders & Stroke | Migraine

and…

The Migraine Trust ← helpfully, this one has a “Calm mode” to tone down the colorscheme of the website!

Particularly useful from the above site are its pages:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: