Chaga Mushrooms’ Immune & Anticancer Potential

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Do Chaga Mushrooms Do?

Chaga mushrooms, which also go by other delightful names including “sterile conk trunk rot” and “black mass”, are a type of fungus that grow on birch trees in cold climates such as Alaska, Northern Canada, Northern Europe, and Siberia.

They’ve enjoyed a long use as a folk remedy in Northern Europe and Siberia, mostly to boost immunity, mostly in the form of a herbal tea.

Let’s see what the science says…

Does it boost the immune system?

It definitely does if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Immunomodulatory Activity of the Water Extract from Medicinal Mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Inonotus obliquus extracts suppress antigen-specific IgE production through the modulation of Th1/Th2 cytokines in ovalbumin-sensitized mice

(cytokines are special proteins that regulate the immune system, and Chaga tells them to tell the body to produce more white blood cells)

Wait, does that mean it increases inflammation?

Definitely not if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Anti-inflammatory effects of orally administered Inonotus obliquus in ulcerative colitis

- Orally administered aqueous extract of Inonotus obliquus ameliorates acute inflammation

Anti-inflammatory things often fight cancer. Does chaga?

Definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies in human cancer patients yet. But for example:

While in vivo human studies are conspicuous by their absence, there have been in vitro human studies, i.e., studies performed on cancerous human cell samples in petri dishes. They are promising:

- Anticancer activities of extracts and compounds from the mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Extract of Innotus obliquus induces G1 cell cycle arrest in human colon cancer cells

- Anticancer activity of Inonotus obliquus extract in human cancer cells

I heard it fights diabetes; does it?

You’ll never see this coming, but: definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any human studies yet. But for example:

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice and potential mechanism

Is it safe?

Honestly, there simply have been no human safety studies to know for sure, or even to establish an appropriate dosage.

Its only-partly-understood effects on blood sugar levels and the immune system may make it more complicated for people with diabetes and/or autoimmune disorders, and such people should definitely seek medical advice before taking chaga.

Additionally, chaga contains a protein that can prevent blood clotting. That might be great by default if you are at risk of blood clots, but not so great if you are already on blood-thinning medication, or otherwise have a bleeding disorder, or are going to have surgery soon.

As with anything, we’re not doctors, let alone your doctors, so please consult yours before trying chaga.

Where can we get it?

We don’t sell it (or anything else), but for your convenience, here’s an example product on Amazon.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Loss, Trauma, and Resilience – by Dr. Pauline Boss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most books about bereavement are focused on grieving healthily and then moving on healthily. And, while it may be said “everyone’s grief is on their own timescale”… society’s expectation is often quite fixed:

“Time will heal”, they say.

But what if it doesn’t? What happens when that’s not possible?

Ambiguous loss occurs when someone is on the one hand “gone”, but on the other hand, not necessarily.

This can be:

- Someone was lost in a way that didn’t leave a body to 100% confirm it

- (e.g. disaster, terrorism, war, murder, missing persons)

- Someone remains physically present but in some ways already “gone”

- (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia, brain injury, coma)

These things stop us continuing as normal, and/but also stop us from moving on as normal.

When either kind of moving forward is made impossible, everything gets frozen in place. How does one deal with that?

Dr. Boss wrote this book for therapists, but its content is equally useful for anyone struggling with ambiguous loss—or who has a loved one who is, in turn, struggling with that.

The book looks at the impact of ambiguous loss on continuing life, and how to navigate that:

- How to be resilient, in the sense of when life tries to break you, to have ways to bend instead.

- How to live with the cognitive dissonance of a loved one who is a sort of “Schrödinger’s person”.

- How, and this is sometimes the biggest one, to manage ambiguous loss in a society that often pushes toward: “it’s been x period of time, come on, get over it now, back to normal”

Will this book heal your heart and resolve your grief? No, it won’t. But what it can do is give a roadmap for nonetheless thriving in life, while gently holding onto whatever we need to along the way.

Click here to check out “Ambiguous loss, Trauma, and Resilience” on Amazon—it can really help

Share This Post

- Someone was lost in a way that didn’t leave a body to 100% confirm it

-

Oven-Roasted Ratatouille

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a supremely low-effort, high-yield dish. It’s a nutritional tour-de-force, and very pleasing to the tastebuds too. We use flageolet beans in this recipe; they are small immature kidney beans. If they’re not available, using kidney beans or really any other legume is fine.

You will need

- 2 large zucchini, sliced

- 2 red peppers, sliced

- 1 large eggplant, sliced and cut into semicircles

- 1 red onion, thinly sliced

- 2 cans chopped tomatoes

- 2 cans flageolet beans, drained and rinsed (or 2 cups same, cooked, drained, and rinsed)

- ½ bulb garlic, crushed

- 2 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 1 tbsp balsamic vinegar

- 1 tbsp black pepper, coarse ground

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tbsp red chili pepper flakes (omit or adjust per your heat preferences)

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Mixed herbs, per your preference. It’s hard to go wrong with this one, but we suggest leaning towards either basil and oregano or rosemary and thyme. We also suggest having some finely chopped to go into the dish, and some held back to go on the dish as a garnish.

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 350℉ / 180℃.

2) Mix all the ingredients (except the tomatoes and herbs) in a big mixing bowl, ensuring even distribution.

2) Add the tomatoes. The reason we didn’t add these before is because it would interfere with the oil being distributed evenly across the vegetables.

3) Transfer to a deep-walled oven tray or an ovenproof dish, and roast for 30 minutes.

4) Stir, add the chopped herbs, stir again, and return to the oven for another 30 minutes.

5) Serve (hot or cold), adding any herb garnish you wish to use.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Lycopene’s Benefits For The Gut, Heart, Brain, & More

- Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

- Capsaicin For Weight Loss And Against Inflammation

- The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

- Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Toe-Tapping Tip For Better Balance

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Balance is critical for health especially in older age, since it’s amazing how much else can go dramatically and suddenly wrong after a fall. So, here’s an exercise to give great balance and stability:

How to do it

You will need:

- Something to hold onto, such as a countertop

- A target on the floor, such as a mark or a coin

The steps:

- Lift one leg up, bring your foot forward, and tap the object in front of you.

- Then, bring that foot back to where it started.

- Next, switch to the other leg and tap.

- Alternate between your right and left legs, shifting back and forth.

- Your goal is to do this for 10 repetitions on each leg without holding on.

How it works:

Whenever you tap, you have to lift one leg up and reach it out in front of you. Doing this requires you to stand on one leg while moving a weight (namely: your other leg), which is something many people, especially upon getting older, are hesitant to do. If you’re unable to stand on one leg, let alone move your center of gravity (per the counterbalance of the other leg) while doing so, you may end up shuffling and walking with your feet sliding across the ground—something you really want to avoid.

For more on all of this plus a visual demonstration, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Fall Special ← this is about not falling, or, failing that, minimizing injury if you do

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

4 things ancient Greeks and Romans got right about mental health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

According to the World Health Organization, about 280 million people worldwide have depression and about one billion have a mental health problem of any kind.

People living in the ancient world also had mental health problems. So, how did they deal with them?

As we’ll see, some of their insights about mental health are still relevant today, even though we might question some of their methods.

Jr Morty/Shutterstock 1. Our mental state is important

Mental health problems such as depression were familiar to people in the ancient world. Homer, the poet famous for the Iliad and Odyssey who lived around the eighth century BC, apparently died after wasting away from depression.

Already in the late fifth century BC, ancient Greek doctors recognised that our health partly depends on the state of our thoughts.

In the Epidemics, a medical text written in around 400BC, an anonymous doctor wrote that our habits about our thinking (as well as our lifestyle, clothing and housing, physical activity and sex) are the main determinants of our health.

Homer, the ancient Greek poet, had depression. Thirasia/Shutterstock 2. Mental health problems can make us ill

Also writing in the Epidemics, an anonymous doctor described one of his patients, Parmeniscus, whose mental state became so bad he grew delirious, and eventually could not speak. He stayed in bed for 14 days before he was cured. We’re not told how.

Later, the famous doctor Galen of Pergamum (129-216AD) observed that people often become sick because of a bad mental state:

It may be that under certain circumstances ‘thinking’ is one of the causes that bring about health or disease because people who get angry about everything and become confused, distressed and frightened for the slightest reason often fall ill for this reason and have a hard time getting over these illnesses.

Galen also described some of his patients who suffered with their mental health, including some who became seriously ill and died. One man had lost money:

He developed a fever that stayed with him for a long time. In his sleep he scolded himself for his loss, regretted it and was agitated until he woke up. While he was awake he continued to waste away from grief. He then became delirious and developed brain fever. He finally fell into a delirium that was obvious from what he said, and he remained in this state until he died.

3. Mental illness can be prevented and treated

In the ancient world, people had many different ways to prevent or treat mental illness.

The philosopher Aristippus, who lived in the fifth century BC, used to advise people to focus on the present to avoid mental disturbance:

concentrate one’s mind on the day, and indeed on that part of the day in which one is acting or thinking. Only the present belongs to us, not the past nor what is anticipated. The former has ceased to exist, and it is uncertain if the latter will exist.

The philosopher Clinias, who lived in the fourth century BC, said that whenever he realised he was becoming angry, he would go and play music on his lyre to calm himself.

Doctors had their own approaches to dealing with mental health problems. Many recommended patients change their lifestyles to adjust their mental states. They advised people to take up a new regime of exercise, adopt a different diet, go travelling by sea, listen to the lectures of philosophers, play games (such as draughts/checkers), and do mental exercises equivalent to the modern crossword or sudoku.

Galen, a famous doctor, believed mental problems were caused by some idea that had taken hold of the mind. Pierre Roche Vigneron/Wikimedia For instance, the physician Caelius Aurelianus (fifth century AD) thought patients suffering from insanity could benefit from a varied diet including fruit and mild wine.

Doctors also advised people to take plant-based medications. For example, the herb hellebore was given to people suffering from paranoia. However, ancient doctors recognised that hellebore could be dangerous as it sometimes induced toxic spasms, killing patients.

Other doctors, such as Galen, had a slightly different view. He believed mental problems were caused by some idea that had taken hold of the mind. He believed mental problems could be cured if this idea was removed from the mind and wrote:

a person whose illness is caused by thinking is only cured by taking care of the false idea that has taken over his mind, not by foods, drinks, [clothing, housing], baths, walking and other such (measures).

Galen thought it was best to deflect his patients’ thoughts away from these false ideas by putting new ideas and emotions in their minds:

I put fear of losing money, political intrigue, drinking poison or other such things in the hearts of others to deflect their thoughts to these things […] In others one should arouse indignation about an injustice, love of rivalry, and the desire to beat others depending on each person’s interest.

4. Addressing mental health needs effort

Generally speaking, the ancients believed keeping our mental state healthy required effort. If we were anxious or angry or despondent, then we needed to do something that brought us the opposite of those emotions.

Watch some comedy, said physician Caelius Aurelianus. VCU Tompkins-McCaw Library/Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA This can be achieved, they thought, by doing some activity that directly countered the emotions we are experiencing.

For example, Caelius Aurelianus said people suffering from depression should do activities that caused them to laugh and be happy, such as going to see a comedy at the theatre.

However, the ancients did not believe any single activity was enough to make our mental state become healthy. The important thing was to make a wholesale change to one’s way of living and thinking.

When it comes to experiencing mental health problems, we clearly have a lot in common with our ancient ancestors. Much of what they said seems as relevant now as it did 2,000 years ago, even if we use different methods and medicines today.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Konstantine Panegyres, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, researching Greco-Roman antiquity, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Love Changes Your Brain

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When we fall in love, have a romantic attachment, or have a sad breakup, there’s a lot going on neurochemically, and also with different parts of the brain taking the wheel. Dr. Shannon Odell explains:

The neurochemistry of love

Of course, not every love will follow this exact pattern, but here’s perhaps the most common one:

Infatuation stage: This early phase is characterized by obsessive thoughts and a strong desire to be with the person. The ventral tegmental area (VTA), the brain’s reward center, becomes highly active, releasing dopamine, one of the feel-good neurotransmitters, which makes love feel intoxicating, similar to addictive substances. Additionally, activity in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for critical thinking and judgment, decreases, causing people to see their partners through “rose-tinted glasses”. However, this intense stage usually lasts only a few months.

Attachment stage: As the relationship progresses, it shifts into a more stable and long-lasting phase. This stage is driven by oxytocin and vasopressin, hormones that promote trust/bonding and arousal, respectively. These same hormones also play a role in family and friendship connections. Oxytocin, in particular, reduces stress hormones, which is why spending time with a loved one can feel so calming.

Heartbreak stage: When a relationship ends, the insular cortex processes emotional and physical pain, making heartbreak feel as painful as a physical injury. Meanwhile, the VTA remains active, leading to intense longing and cravings for the lost partner, similar to withdrawal symptoms. The stress axis also activates, causing distress and restlessness. Over time, higher brain regions help regulate these emotions. Healing strategies such as exercise, socializing, and listening to music can help by triggering dopamine release and easing the pain of heartbreak.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why do some people’s hair and nails grow quicker than mine?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Throughout recorded history, our hair and nails played an important role in signifying who we are and our social status. You could say, they separate the caveman from businessman.

It was no surprise then that many of us found a new level of appreciation for our hairdressers and nail artists during the COVID lockdowns. Even Taylor Swift reported she cut her own hair during lockdown.

So, what would happen if all this hair and nail grooming got too much for us and we decided to give it all up. Would our hair and nails just keep on growing?

The answer is yes. The hair on our head grows, on average, 1 centimeter per month, while our fingernails grow an average of just over 3 millimetres.

When left unchecked, our hair and nails can grow to impressive lengths. Aliia Nasyrova, known as the Ukrainian Rapunzel, holds the world record for the longest locks on a living woman, which measure an impressive 257.33 cm.

When it comes to record-breaking fingernails, Diana Armstrong from the United States holds that record at 1,306.58 cm.

Most of us, however, get regular haircuts and trim our nails – some with greater frequency than others. So why do some people’s hair and nails grow more quickly?

Jari Lobo/Pexels Remind me, what are they made out of?

Hair and nails are made mostly from keratin. Both grow from matrix cells below the skin and grow through different patterns of cell division.

Nails grow steadily from the matrix cells, which sit under the skin at the base of the nail. These cells divide, pushing the older cells forward. As they grow, the new cells slide along the nail bed – the flat area under the fingernail which looks pink because of its rich blood supply.

Nails, like hair, are made mostly of keratin. Scott Gruber/Unsplash A hair also starts growing from the matrix cells, eventually forming the visible part of the hair – the shaft. The hair shaft grows from a root that sits under the skin and is wrapped in a sac known as the hair follicle.

This sac has a nerve supply (which is why it hurts to pull out a hair), oil-producing glands that lubricate the hair and a tiny muscle that makes your hair stand up when it’s cold.

At the follicle’s base is the hair bulb, which contains the all-important hair papilla that supplies blood to the follicle.

Matrix cells near the papilla divide to produce new hair cells, which then harden and form the hair shaft. As the new hair cells are made, the hair is pushed up above the skin and the hair grows.

But the papilla also plays an integral part in regulating hair growth cycles, as it sends signals to the stem cells to move to the base of the follicle and form a hair matrix. Matrix cells then get signals to divide and start a new growth phase.

Unlike nails, our hair grows in cycles

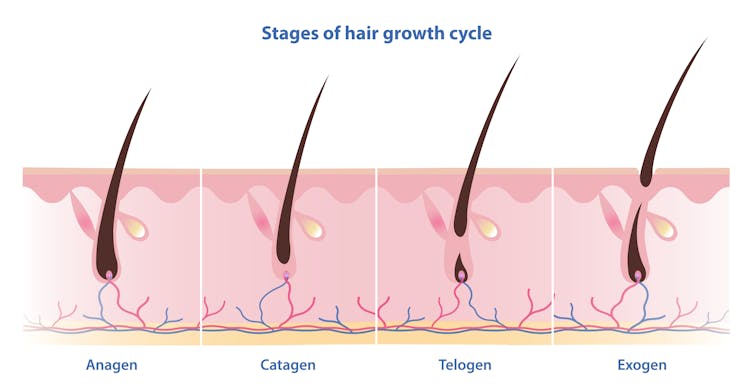

Scientists have identified four phases of hair growth, the:

- anagen or growth phase, which lasts between two and eight years

- catagen or transition phase, when growth slows down, lasting around two weeks

- telogen or resting phase, when there is no growth at all. This usually lasts two to three months

- exogen or shedding phase, when the hair falls out and is replaced by the new hair growing from the same follicle. This starts the process all over again.

Hair follicles enter these phases at different times so we’re not left bald. Mosterpiece/Shutterstock Each follicle goes through this cycle 10–30 times in its lifespan.

If all of our hair follicles grew at the same rate and entered the same phases simultaneously, there would be times when we would all be bald. That doesn’t usually happen: at any given time, only one in ten hairs is in the resting phase.

While we lose about 100–150 hairs daily, the average person has 100,000 hairs on their head, so we barely notice this natural shedding.

So what affects the speed of growth?

Genetics is the most significant factor. While hair growth rates vary between individuals, they tend to be consistent among family members.

Nails are also influenced by genetics, as siblings, especially identical twins, tend to have similar nail growth rates.

Genetics have the biggest impact on growth speed. Cottonbro Studio/Pexels But there are also other influences.

Age makes a difference to hair and nail growth, even in healthy people. Younger people generally have faster growth rates because of the slowing metabolism and cell division that comes with ageing.

Hormonal changes can have an impact. Pregnancy often accelerates hair and nail growth rates, while menopause and high levels of the stress hormone cortisol can slow growth rates.

Nutrition also changes hair and nail strength and growth rate. While hair and nails are made mostly of keratin, they also contain water, fats and various minerals. As hair and nails keep growing, these minerals need to be replaced.

That’s why a balanced diet that includes sufficient nutrients to support your hair and nails is essential for maintaining their health.

Nutrition can impact hair and nail growth. Cottonbro Studio/Pexels Nutrient deficiencies may contribute to hair loss and nail breakage by disrupting their growth cycle or weakening their structure. Iron and zinc deficiencies, for example, have both been linked to hair loss and brittle nails.

This may explain why thick hair and strong, well-groomed nails have long been associated with perception of good health and high status.

However, not all perceptions are true.

No, hair and nails don’t grow after death

A persistent myth that may relate to the legends of vampires is that hair and nails continue to grow after we die.

In reality, they only appear to do so. As the body dehydrates after death, the skin shrinks, making hair and nails seem longer.

Morticians are well aware of this phenomenon and some inject tissue filler into the deceased’s fingertips to minimise this effect.

So, it seems that living or dead, there is no escape from the never-ending task of caring for our hair and nails.

Michelle Moscova, Adjunct Associate Professor, Anatomy, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: