Aspirin, CVD Risk, & Potential Counter-Risks

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Aspirin Pros & Cons

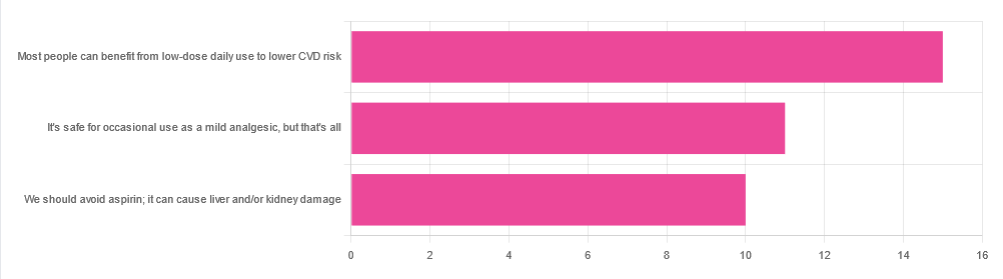

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked your health-related opinion of aspirin, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of responses:

- About 42% said “Most people can benefit from low-dose daily use to lower CVD risk”

- About 31% said “It’s safe for occasional use as a mild analgesic, but that’s all”

- About 28% said “We should avoid aspirin; it can cause liver and/or kidney damage”

So, what does the science say?

Most people can benefit from low-dose daily aspirin use to lower the risk of cardiovascular disease: True or False?

True or False depending on what we mean by “benefit from”. You see, it works by inhibiting platelet function, which means it simultaneously:

- decreases the risk of atherothrombosis

- increases the risk of bleeding, especially in the gastrointestinal tract

When it comes to balancing these things and deciding whether the benefit merits the risk, you might be asking yourself: “which am I most likely to die from?” and the answer is: neither

While aspirin is associated with a significant improvement in cardiovascular disease outcomes in total, it is not significantly associated with reductions in cardiovascular disease mortality or all-cause mortality.

In other words: speaking in statistical generalizations of course, it may improve your recovery from minor cardiac events but is unlikely to help against fatal ones

The current prevailing professional (amongst cardiologists) consensus is that it may be recommended for secondary prevention of ASCVD (i.e. if you have a history of CVD), but not for primary prevention (i.e. if you have no history of CVD). Note: this means personal history, not family history.

In the words of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology:

❝Low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg orally daily) might be considered for the primary prevention of ASCVD among select adults 40 to 70 years of age who are at higher ASCVD risk but not at increased bleeding risk (S4.6-1–S4.6-8).

Low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg orally daily) should not be administered on a routine basis for the primary prevention of ASCVD among adults >70 years of age (S4.6-9).

Low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg orally daily) should not be administered for the primary prevention of ASCVD among adults of any age who are at increased risk of bleeding (S4.6-10).❞

~ Dr. Donna Arnett et al. (those section references are where you can find this information in the document)

Read in full: Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology

Or if you’d prefer a more pop-science presentation:

Many older adults still use aspirin for CVD prevention, contrary to clinical guidance

Aspirin can cause liver and/or kidney damage: True or False?

True, but that doesn’t mean we must necessarily abstain, so much as exercise caution.

Aspirin is (at recommended doses) not usually hepatotoxic (toxic to the liver), but there is a strong association between aspirin use in children and the development of Reye’s syndrome, a disease involving encephalopathy and a fatty liver. For this reason, most places have an official recommendation that aspirin not be used by children (cut-off age varies from place to place, for example 12 in the US and 16 in the UK, but the key idea is: it’s potentially dangerous for those who are not fully grown).

Aspirin is well-established as nephrotoxic (toxic to the kidneys), however, the toxicity is sufficiently low that this is not expected to be a problem to otherwise healthy adults taking it at no more than the recommended dose.

For numbers, symptoms, and treatment, see this very clear and helpful resource:

An evidence based flowchart to guide the management of acute salicylate (aspirin) overdose

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Older adults need another COVID-19 vaccine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- The CDC recommends people 65 and older and immunocompromised people receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring—if at least four months have passed since they received a COVID-19 vaccine.

- Updated COVID-19 vaccines are effective at protecting against severe illness, hospitalization, death, and long COVID.

- The CDC also shortened the isolation period for people who are sick with COVID-19.

Last week, the CDC said people 65 and older should receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring. The recommendation also applies to immunocompromised people, who were already eligible for an additional dose.

Older adults made up two-thirds of COVID-19-related hospitalizations between October 2023 and January 2024, so enhancing protection for this group is critical.

The CDC also shortened the isolation period for people who are sick with COVID-19, although the contagiousness of COVID-19 has not changed.

Read on to learn more about the CDC’s updated vaccination and isolation recommendations.

Who is eligible for another COVID-19 vaccine this spring?

The CDC recommends that people ages 65 and older and immunocompromised people receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring—if at least four months have passed since they received a COVID-19 vaccine. It’s safe to receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer, Moderna, or Novavax, regardless of which COVID-19 vaccines you received in the past.

Updated COVID-19 vaccines are available at pharmacies, local clinics, or doctor’s offices. Visit Vaccines.gov to find an appointment near you.

Under- and uninsured adults can get the updated COVID-19 vaccine for free through the CDC’s Bridge Access Program. If you’re over 60 and unable to leave your home, call the Aging Network at 1-800-677-1116 to learn about free at-home vaccination options.

What are the benefits of staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines?

Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines prevents severe illness, hospitalization, death, and long COVID.

Additionally, the CDC says staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines is a safer and more reliable way to build protection against COVID-19 than getting sick from COVID-19.

What are the new COVID-19 isolation guidelines?

According to the CDC’s general respiratory virus guidance, people who are sick with COVID-19 or another common respiratory illness, like the flu or RSV, should isolate until they’ve been fever-free for at least 24 hours without the use of fever-reducing medication and their symptoms improve.

After that, the CDC recommends taking additional precautions for the next five days: wearing a well-fitting mask, limiting close contact with others, and improving ventilation in your home if you live with others.

If you’re sick with COVID-19, you can infect others for five to 12 days, or longer. Moderately or severely immunocompromised patients may remain infectious beyond 20 days.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

-

Guava vs Pineapple – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing guava to pineapple, we picked the guava.

Why?

Pineapple is great, but guava just beats it in most ways:

In terms of macros, guava has nearly 4x the fiber and nearly 5x the protein, for the same carbs, giving it the notably lower glycemic index. An easy win for guava in this category.

In the category of vitamins, guava has a lot more of vitamins A, B2, B3, B5, B9, C, E, K, and choline, while pineapple has marginally more vitamin B1. Another clear win for guava.

When it comes to minerals, guava has more calcium, copper, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while pineapple has more iron and manganese. One more win for guava.

One big thing in pineapple’s favor is that it contains bromelain, which is an enzyme* found in pineapple (and only in pineapple), that has many very healthful properties, some of them unique to bromelain (and thus: unique to pineapple)

*actually a combination of enzymes, but most often referred to collectively in the singular. But when you do see it referred to as “they”, that’s what that means.

However cool that is, we think it unfair to weight it against guava winning in every other category, so we still say guava gets the overall win.

Of course, enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Let’s Get Fruity: Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Built to Move – by Kelly starrett & Juliet Starrett

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In our everyday lives, for most of us anyway, it’s not too important to be able to run a marathon or leg-press a car. Rather more important, however, are such things as:

- being able to get up from the floor comfortably

- reach something on a high shelf without twinging a shoulder

- being able to put our socks on without making a whole plan around this task

- get accidentally knocked by an energetic dog or child and not put our back out

- etc

Starrett and Starrett, of “becoming a supple leopard” fame, lay out for us how to make sure our mobility stays great. And, if it’s not already where it needs to be, how to get there.

The “ten essential habits” mentioned in the subtitle “ten essential habits to help you move freely and live fully”, in fact also come with ten tests. No, not in the sense of arduous trials, but rather, mobility tests.

For each test, it’s explained to us how to score it out of ten (this is an objective assessment, not subjective). It’s then explained how to “level up” whatever score we got, with different advices for different levels of mobility or immobility. And if we got a ten, then of course, we just build the appropriate recommended habit into our daily life, to keep it that way.

The writing style is casual throughout, and a strong point of the book is its very clear illustrations, too.

Bottom line: if you’d like to gain/maintain good mobility (at any age), this book gives a very reliable outline for doing so.

Click here to check out Built to Move, and take care of your body!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Kidney Beans vs Pinto Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kidney beans to pinto beans, we picked the pinto.

Why?

Looking at the macros first, pinto beans have slightly more protein and carbs, and a lot more fiber, making them the all-round “more food per food” choice.

In the vitamins category, kidney beans have more of vitamins B3, C, and K, while pinto beans have more of vitamins B1, B2, B6, B9, E, and choline; another win for pinto beans. In kidney beans’ defense though, with the exception of vitamin E (31x more in pinto beans) the margins of difference are small for the rest of these vitamins, making kidney beans a close runner-up. Still, at least a nominal win for pinto beans here, by the numbers.

When it comes to minerals, kidney beans are not higher in any minerals, while pinto beans have more calcium, copper, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium. In kidney beans’ defense, though, with the exception of selenium (5–6x more in pinto beans) the margins of difference are small for the rest of these minerals, making kidney beans a fine choice here too. Once again though, a winner is declarable here by the numbers, and it’s pinto beans.

Adding up the three wins makes for one big win for pinto beans. Still, enjoy either or both, because kidney beans are great too, and so is diversity!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Oh She Glows Cookbook – by Angela Liddon

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Let’s get the criticism out of the way first: notwithstanding the subtitle promising over 100 recipes, there are about 80-odd here, if we discount recipes that are no-brainer things like smoothies, sides such as for example “roasted garlic”, or meta-ingredients such as oat flour (instructions: blend the oats and you get oat flour).

The other criticism is more subjective: if you are like this reviewer, you will want to add more seasonings than recommended to most of the recipes. But that’s easy enough to do.

As for the rest: this is a very healthy cookbook, and quite wide-ranging and versatile, with recipes that are homely, with a lot of emphasis on comfort foods (but still, healthy), though certainly some are perfectly worthy of entertaining too.

A nice bonus of this book is that it offers a lot of available substitutions (much like we do at 10almonds), and also ways of turning the recipe into something else entirely with just a small change. This trait more than makes up for the slight swindle in terms of number of recipes, since some of the recipes have bonus recipes snuck in.

Bottom line: if you’d like to broaden your plant-based cooking range, this book is a fine option for expanding your repertoire.

Click here to check out The Oh She Glows Cookbook, and indeed glow!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Calm Your Inflammation – by Dr. Brenda Tidwell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The book starts with an overview of inflammation, both acute and chronic, before diving into how to reduce the latter kind (acute inflammation being usually necessary and helpful, usually fighting disease rather than creating it).

The advice in the book is not just dietary, and covers lifestyle interventions too, including exercise etc—and how to strike the right balance, since the wrong kind of exercise or too much of it can sabotage our efforts. Similarly, Dr. Tidwell doesn’t just say such things as “manage stress” but also provides 10 ways of doing so, and so forth for other vectors of inflammation-control. She does cover dietary things as well though, including supplements where applicable, and the role of gut health, sleep, and other factors.

The style of the book is quite entry-level pop-science, designed to be readable and comprehensible to all, without unduly dumbing-down. In terms of hard science or jargon, there are 6 pages of bibliography and 3 pages of glossary, so it’s neither devoid of such nor overwhelmed by it.

Bottom line: if fighting inflammation is a priority for you, then this book is an excellent primer.

Click here to check out Calm Your Inflammation, and indeed calm your inflammation!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: