Are Supplements Worth Taking?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝There seems to be a lot of suggestions to take supplements for every thing, from your head to your toes. I know it’s up to the individual but what are the facts or stats to support taking them versus not?❞

Short answer:

- supplementary vitamins and minerals are probably neither needed nor beneficial for most (more on this later) people, with the exception of vitamin D which most people over a certain age need unless they are white and getting a lot of sun.

- other kinds of supplement can be very beneficial or useless, depending on what they are, of course, and also your own personal physiology.

With regard to vitamins and minerals, in most cases they should be covered by a healthy balanced diet, and the bioavailability is usually better from food anyway (bearing in mind, we say vitamin such-and-such, or name an elemental mineral, but there are usually multiple, often many, forms of each—and supplements will usually use whatever is cheapest to produce and most chemically stable).

However! It is also quite common for food to be grown in whatever way is cheapest and produces the greatest visible yield, rather than for micronutrient coverage.

This goes for most if not all plants, and it goes extra for animals (because of the greater costs and inefficiencies involved in rearing animals).

We wrote about this a while back in a mythbusting edition of 10almonds, covering:

- Food is less nutritious now than it used to be: True or False?

- Supplements aren’t absorbed properly and thus are a waste of money: True or False?

- We can get everything we need from our diet: True or False?

You can read the answers and explanations, and see the science that we presented, here:

Do We Need Supplements, And Do They Work?

You may be wondering: what was that about “most (more on this later) people”?

Sometimes someone will have a nutrient deficiency that can’t be easily remedied with diet. Often this occurs when their body:

- has trouble absorbing that nutrient, or

- does something inconvenient with it that makes a lot of it unusable when it gets it.

…which is why calcium, iron, vitamin B12, and vitamin D are quite common supplements to get prescribed by doctors after a certain age.

Still, it’s best to try getting things from one’s diet first all of all, of course.

Things we can’t (reasonably) get from food

This is another category entirely. There are many supplements that are convenient forms of things readily found in a lot of food, such as vitamins and minerals, or phytochemicals like quercetin, fisetin, and lycopene (to name just a few of very many).

Then there are things not readily found in food, or at least, not in food that’s readily available in supermarkets.

For example, if you go to your local supermarket and ask where the mimosa is, they’ll try to sell you a cocktail mix instead of the roots, bark, or leaves of a tropical tree. It is also unlikely they’ll stock lion’s mane mushroom, or reishi.

If perchance you do get the chance to acquire fresh lion’s mane mushroom, by the way, give it a try! It’s delicious shallow-fried in a little olive oil with black pepper and garlic.

In short, this last category, the things most of us can’t reasonably get from food without going far out of our way, are the kind of thing whereby supplements actually can be helpful.

And yet, still, not every supplement has evidence to support the claims made by its sellers, so it’s good to do your research beforehand. We do that on Mondays, with our “Research Review Monday” editions, of which you can find in our searchable research review archive ← we also review some drugs that can’t be classified as supplements, but mostly, it’s supplements.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Exercises for Aging-Ankles

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Can Ankles Deterioration be Stopped?

As we all know (or have experienced!), Ankle mobility deteriorates with age.

We’re here to argue that it’s not all doom and gloom!

(In fact, we’ve written about keeping our feet, and associated body parts, healthy here).

This video by “Livinleggings” (below) provides a great argument that yes, ankle deterioration can be stopped, or even reversed. It’s a must-watch for anyone from yoga enthusiasts to gym warriors who might be unknowingly crippling their ankle-health.

How We Can Prioritise Our Ankles

Poor ankle flexibility isn’t just an inconvenience – it’s a direct route to knee issues, hip hiccups, and back pain. More importantly, ankle strength is a core component of building overall mobility.

With 12 muscles in the ankle, it can be overwhelming to work out which to strengthen – and how. But fear not, we can prioritise three of the twelve: the calf duo (gastrocnemius and soleus) and the shin’s main muscle, the tibialis anterior.

The first step is to test yourself! A simple wall test reveals any hidden truths about your ankle flexibility. Go to the 1:55 point in the video to see how it’s done.

If you can’t do it, you’ve got work to be done.

If you read the book we recommended on great functional exercises for seniors, then you may already be familiar with some super ankle exercises.

Otherwise, these four ankle exercises are a great starting point:

How did you find that video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

The Problem With Sweeteners

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The WHO’s view on sugar-free sweeteners

The WHO has released a report offering guidance regards the use of sugar-free sweeteners as part of a weight-loss effort.

In a nutshell, the guidance is: don’t

- Here’s the report itself: Use of non-sugar sweeteners: WHO guideline

- Here’s the WHO’s own press release about it: WHO advises not to use non-sugar sweeteners for weight control in newly released guideline

- And it was based on this huge systematic review: Health effects of the use of non-sugar sweeteners: a systematic review and meta-analysis

They make for interesting reading, so if you don’t have time now, you might want to just quickly open and bookmark them for later!

Some salient bits and pieces:

Besides that some sweeteners can cause gastro-intestinal problems, a big problem is desensitization:

Because many sugar substitutes are many times (in some cases, hundreds of times) sweeter than sugar, this leads to other sweet foods tasting more bland, causing people to crave sweeter and sweeter foods for the same satisfaction level.

You can imagine how that’s not a spiral that’s good for the health!

The WHO recommendation applies to artificial and naturally-occurring non-sugar sweeteners, including:

- Acesulfame K

- Advantame

- Aspartame

- Cyclamates

- Neotame

- Saccharin

- Stevia

Sucralose and erythritol, by the way, technically are sugars, just not “that kind of sugar” so they didn’t make the list of non-sugar sweeteners.

That said, a recent study did find that erythritol was linked to a higher risk of heart attack, stroke, and early death, so it may not be an amazing sweetener either:

Read: The artificial sweetener erythritol and cardiovascular event risk

Want to know a good way of staying healthy in the context of sweeteners?

Just get used to using less. Your taste buds will adapt, and you’ll get just as much pleasure as before, from progressively less sweetening agent.

Share This Post

-

Why are tall people more likely to get cancer? What we know, don’t know and suspect

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People who are taller are at greater risk of developing cancer. The World Cancer Research Fund reports there is strong evidence taller people have a higher chance of of developing cancer of the:

- pancreas

- large bowel

- uterus (endometrium)

- ovary

- prostate

- kidney

- skin (melanoma) and

- breast (pre- and post-menopausal).

But why? Here’s what we know, don’t know and suspect.

Pexels/Andrea Piacquadio Height does increase your cancer risk – but only by a very small amount. Christian Vinces/Shutterstock A well established pattern

The UK Million Women Study found that for 15 of the 17 cancers they investigated, the taller you are the more likely you are to have them.

It found that overall, each ten-centimetre increase in height increased the risk of developing a cancer by about 16%. A similar increase has been found in men.

Let’s put that in perspective. If about 45 in every 10,000 women of average height (about 165 centimetres) develop cancer each year, then about 52 in each 10,000 women who are 175 centimetres tall would get cancer. That’s only an extra seven cancers.

So, it’s actually a pretty small increase in risk.

Another study found 22 of 23 cancers occurred more commonly in taller than in shorter people.

Why?

The relationship between height and cancer risk occurs across ethnicities and income levels, as well as in studies that have looked at genes that predict height.

These results suggest there is a biological reason for the link between cancer and height.

While it is not completely clear why, there are a couple of strong theories.

The first is linked to the fact a taller person will have more cells. For example, a tall person probably has a longer large bowel with more cells and thus more entries in the large bowel cancer lottery than a shorter person.

Scientists think cancer develops through an accumulation of damage to genes that can occur in a cell when it divides to create new cells.

The more times a cell divides, the more likely it is that genetic damage will occur and be passed onto the new cells.

The more damage that accumulates, the more likely it is that a cancer will develop.

A person with more cells in their body will have more cell divisions and thus potentially more chance that a cancer will develop in one of them.

Some research supports the idea having more cells is the reason tall people develop cancer more and may explain to some extent why men are more likely to get cancer than women (because they are, on average, taller than women).

However, it’s not clear height is related to the size of all organs (for example, do taller women have bigger breasts or bigger ovaries?).

One study tried to assess this. It found that while organ mass explained the height-cancer relationship in eight of 15 cancers assessed, there were seven others where organ mass did not explain the relationship with height.

It is worth noting this study was quite limited by the amount of data they had on organ mass.

Is it because tall people have more cells? Halfpoint/Shutterstock Another theory is that there is a common factor that makes people taller as well as increasing their cancer risk.

One possibility is a hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). This hormone helps children grow and then continues to have an important role in driving cell growth and cell division in adults.

This is an important function. Our bodies need to produce new cells when old ones are damaged or get old. Think of all the skin cells that come off when you use a good body scrub. Those cells need to be replaced so our skin doesn’t wear out.

However, we can get too much of a good thing. Some studies have found people who have higher IGF-1 levels than average have a higher risk of developing breast or prostate cancer.

But again, this has not been a consistent finding for all cancer types.

It is likely that both explanations (more cells and more IGF-1) play a role.

But more research is needed to really understand why taller people get cancer and whether this information could be used to prevent or even treat cancers.

I’m tall. What should I do?

If you are more LeBron James than Lionel Messi when it comes to height, what can you do?

Firstly, remember height only increases cancer risk by a very small amount.

Secondly, there are many things all of us can do to reduce our cancer risk, and those things have a much, much greater effect on cancer risk than height.

We can take a look at our lifestyle. Try to:

- eat a healthy diet

- exercise regularly

- maintain a healthy weight

- be careful in the sun

- limit alcohol consumption.

And, most importantly, don’t smoke!

If we all did these things we could vastly reduce the amount of cancer.

You can also take part in cancer screening programs that help pick up cancers of the breast, cervix and bowel early so they can be treated successfully.

Finally, take heart! Research also tells us that being taller might just reduce your chance of having a heart attack or stroke.

Susan Jordan, Associate Professor of Epidemiology, The University of Queensland and Karen Tuesley, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Public Health, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

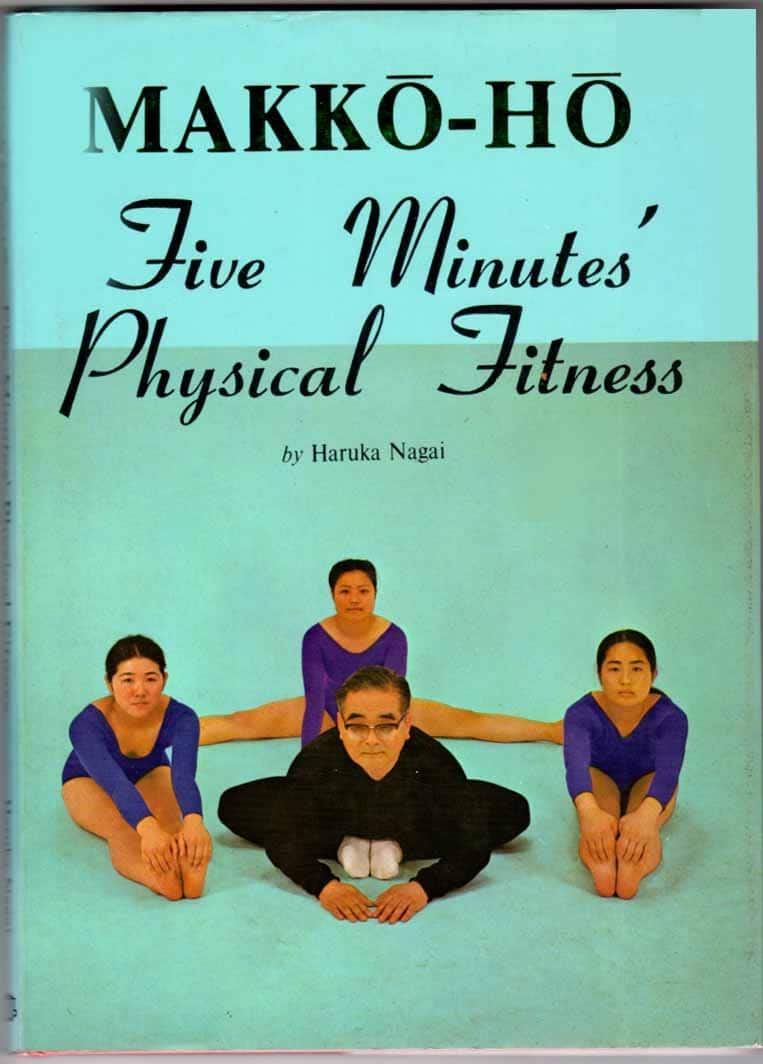

Makkō-Hō – by Haruka Nagai

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve all heard the claims, “Fluent in 3 Months!”, “Russian in Two Weeks!”, “Overnight Mandarin Chinese”, “15-Minute Arabic!”, “Instant Italian!”.

We see the same in the world of health and fitness too. So how does this one’s claim of “five minutes’ physical fitness” hold up?

Well, it is 5 minutes per day. And indeed, the author writes:

❝The total time [to do these exercises], then, is only one minute and thirty seconds. This series I call one round. When it has been completed, execute another complete round. You should find the exercises easier to do the second time. Executed this way, the exercsies will prove very effective, though they take only three minutes in all. After you have leaned back into the final position, you must remain in that posture for one minute. That brings the total time to four minutes. Even when [some small additions] are added, it takes only five minutes at most.❞

The exercises themselves are from makkō-hō, which is a kind of Japanese dynamic yoga. They involve repetitions of (mostly) moving stretches with good form, and are excellent for mobility and general health, keeping us supple and robust as we get older.

The text descriptions are clear, as are the diagrams and photos. The language is a little dated, as this book was written in the 1970s, but the techniques themselves are timeless.

Bottom line: consider it a 5-minute anti-aging regimen. And, as Nagai says, “the person who cannot find 5 minutes out of 24 hours, was never truly interested in their health”.

Click here to check out Makkō-Hō and schedule your five minutes!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

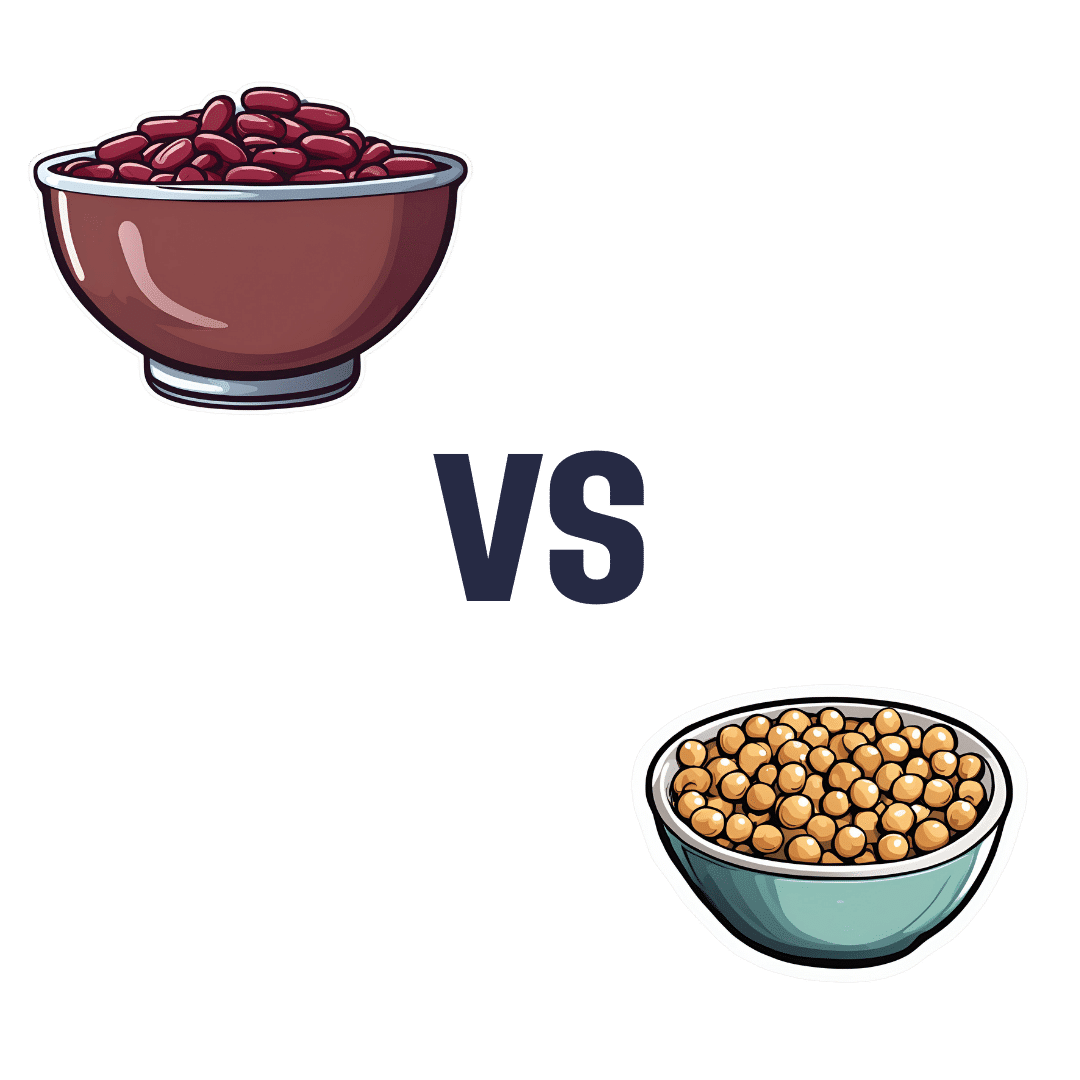

Kidney Beans vs Chickpeas – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kidney beans to chickpeas, we picked the chickpeas.

Why?

Both are great! But there’s a clear winner here today:

In terms of macros, chickpeas have more protein, carbs, and fiber, making them the more nutrient-dense option in this category.

In the category of vitamins, kidney beans have more of vitamins B1, B3, and K, while chickpeas have more of vitamins A, B2, B5, B6, B7, B9, C, E, and choline, taking the victory again here.

When it comes to minerals, it’s a similar story: kidney beans have more potassium, while chickpeas have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc. Another easy win for chickpeas.

Adding up the three wins makes chickpeas the clear overall winner, but of course, as ever, enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can a child legally take puberty blockers? What if their parents disagree?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Young people’s access to gender-affirming medical care has been making headlines this week.

Today, federal Health Minister Mark Butler announced a review into health care for trans and gender-diverse children and adolescents. The National Health and Medical Research Council will conduct the review.

Yesterday, The Australian published an open letter to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese calling for a federal inquiry, and a nationwide pause on puberty blockers and hormone therapy for minors.

This followed Queensland Health Minister Tim Nicholls earlier this week announcing an immediate pause on access to puberty blockers and hormone therapies for new patients under 18 in the state’s public health system, pending a review.

In the United States, President Donald Trump signed an executive order this week directing federal agencies to restrict access to gender-affirming care for anyone under 19.

This recent wave of political attention might imply gender-affirming care for young people is risky, controversial, perhaps even new.

But Australian courts have already extensively tested questions about its legitimacy, the conditions under which it can be provided, and the scope and limits of parental powers to authorise it.

MirasWonderland/Shutterstock What are puberty blockers?

Puberty blockers suppress the release of oestrogen and testosterone, which are primarily responsible for the physical changes associated with puberty. They are generally safe and used in paediatric medicine for various conditions, including precocious (early) puberty, hormone disorders and some hormone-sensitive cancers.

International and domestic standards of care state that puberty blockers are reversible, non-harmful, and can prevent young people from experiencing the distress of undergoing a puberty that does not align with their gender identity. They also give young people time to develop the maturity needed to make informed decisions about more permanent medical interventions further down the line.

Puberty blockers are one type of gender-affirming care. This care includes medical, psychological and social interventions to support transgender, gender-diverse and, in some cases, intersex people.

Young people in Australia need a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria to receive this care. Gender dysphoria is defined as the psychological distress that can arise when a person’s gender identity does not align with their sex assigned at birth. This diagnosis is only granted after an exhaustive and often onerous medical assessment.

After a diagnosis, treatment may involve hormones such as oestrogen or testosterone and/or puberty-blocking medications.

Hormone therapies involving oestrogen and testosterone are only prescribed in Australia once a young person has been deemed capable of giving informed consent, usually around the age of 16. For puberty blockers, parents can consent at a younger age.

Gender dysphoria comes with considerable psychological distress. slexp880/Shutterstock Can a child legally access puberty blockers?

Gender-affirming care has been the subject of extensive debate in the Family Court of Australia (now the Federal Circuit and Family Court).

Between 2004 and 2017, every minor who wanted to access gender-affirming care had to apply for a judge to approve it. However, medical professionals, human rights organisations and some judges condemned this process.

In research for my forthcoming book, I found the Family Court has heard at least 99 cases about a young person’s gender-affirming care since 2004. Across these cases, the court examined the potential risks of gender-affirming treatment and considered whether parents should have the authority to consent on their child’s behalf.

When determining whether parents can consent to a particular medical procedure for their child, the court must consider whether the treatment is “therapeutic” and whether there is a significant risk of a wrong decision being made.

However, in a landmark 2017 case, the court ruled that judicial oversight was not required because gender-affirming treatments meet the standards of normal medical care.

It reasoned that because these therapies address an internationally recognised medical condition, are supported by leading professional medical organisations, and are backed by robust clinical research, there is no justification for treating them differently from any other standard medical intervention. These principles still stand today.

What if parents disagree?

Sometimes parents disagree with decisions about gender-affirming care made by their child, or each other.

As with all forms of health care, under Australian law, parents and legal guardians are responsible for making medical decisions on behalf of their children. That responsibility usually shifts once those children reach a sufficient age and level of maturity to make their own decisions.

However, in another landmark case in 2020, the court ruled gender-affirming treatments cannot be given to minors without consent from both parents, even if the child is capable of providing their own consent. This means that if there is any disagreement among parents and the young person about either their capacity to consent or the legitimacy of the treatment, only a judge can authorise it.

In such instances, the court must assess whether the proposed treatment is in the child’s best interests and make a determination accordingly. Again, these principals apply today.

If a parent disagrees with their child, the matter can go to court. PeopleImages.com – Yuri A/Shutterstock Have the courts ever denied care?

Across the at least 99 cases the court has heard about gender-affirming care since 2004, 17 have involved a parent opposing the treatment and one has involved neither parent supporting it.

Regardless of parental support, in every case, the court has been responsible for determining whether gender-affirming treatment was in the child’s best interests. These decisions were based on medical evidence, expert testimony, and the specific circumstances of the young person involved.

In all cases bar one, the court has found overwhelming evidence to support gender-affirming care, and approved it.

Supporting transgender young people

The history of Australia’s legal debates about gender-affirming care shows it has already been the subject of intense legal and medical scrutiny.

Gender-affirming care is already difficult for young people to access, with many lacking the parental support required or facing other barriers to care.

Gender-affirming care is potentially life-saving, or at the very least life-affirming. It almost invariably leads to better social and emotional outcomes. Further restricting access is not the “protection” its opponents claim.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. For LGBTQIA+ peer support and resources, you can also contact Switchboard, QLife (call 1800 184 527), Queerspace, Transcend Australia (support for trans, gender-diverse, and non-binary young people and their families) or Minus18 (resources and community support for LGBTQIA+ young people).

Matthew Mitchell, Lecturer in Criminology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: