Apples vs Carrots – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apples to carrots, we picked the carrots.

Why?

Both are sweet crunchy snacks, both rightly considered very healthy options, but one comes out clearly on top…

Both contain lots of antioxidants, albeit mostly different ones. They’re both good for this.

Looking at their macros, however, apples have more carbs while carrots have more fiber. The carb:fiber ratio in apples is already sufficient to make them very healthy, but carrots do win.

In the category of vitamins, carrots have many times more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, C, E, K, and choline. Apples are not higher in any vitamins.

In terms of minerals, carrots have a lot more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Apples are not higher in any minerals.

If “an apple a day keeps the doctor away”, what might a carrot a day do?

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Sugar: From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose C’s

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We speak often about the importance of dietary diversity, and of that, especially diversity of plants in one’s diet, but we’ve never really focused on it as a main feature, so that’s what we’re going to do today.

Specifically, you may have heard the advice to “eat 30 different kinds of plants per week”. But where does that come from, and is it just a number out of a hat?

The magic number?

It is not, in fact, a number out of a hat. It’s from a big (n=11,336) study into what things affect the gut microbiome for better or for worse. It was an observational population study, championing “citizen science” in which volunteers tracked various things and collected and sent in various samples for analysis.

The most significant finding of this study was that those who consumed more than 30 different kinds of plants per week, had a much better gut microbiome than those who consumed fewer than 10 different kinds of plants per week (there is a bell curve at play, and it gets steep around 10 and 30):

American Gut: an Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research

Why do I care about having a good gut microbiome?

Gut health affects almost every other kind of health; it’s been called “the second brain” for the various neurotransmitters and other hormones it directly makes or indirectly regulates (which in turn affect every part of your body), and of course there is the vagus nerve connecting it directly to the brain, impacting everything from food cravings to mood swings to sleep habits.

See also:

Any other benefits?

Yes there are! Let’s not forget: as we see often in our “This or That” section, different foods can be strong or weak in different areas of nutrition, so unless we want to whip out a calculator and database every time we make food choices, a good way to cover everything is to simply eat a diverse diet.

And that goes not just for vitamins and minerals (which would be true of animal products also), but in the case of plants, a wide range of health-giving phytochemicals too:

Measuring Dietary Botanical Diversity as a Proxy for Phytochemical Exposure

Ok, I’m sold, but 30 is a lot!

It is, but you don’t have to do all 30 in your first week of focusing on this, if you’re not already accustomed to such diversity. You can add in one or two new ones each time you go shopping, and build it up.

As for “what counts”: we’re counting unprocessed or minimally-processed plants. So for example, an apple is an apple, as are dried apple slices, as is apple sauce. Any or all of those would count as 1 plant type.

Note also that we’re counting types, not totals. If you’re having apple slices with apple sauce, for some reason? That still only counts as 1.

However, while apple sauce still counts as apples (minimally processed), you cannot eat a cake and say “that’s 2 because there was wheat and sugar cane somewhere in its dim and distant history”.

Nor is your morning espresso a fruit (by virtue of coffee beans being the fruit of the plant, botanically speaking). However, it would count as 1 plant type if you eat actual coffee beans—this writer has been known to snack on such; they’re only healthy in very small portions though, because their saturated fat content is a little high.

You, however, count grains in general, as well as nuts and seeds, not just fruits and vegetables. As for herbs and spices, they count for ¼ each, except for salt, which might get lumped in with spices but is of course not a plant.

How to do it

There’s a reason we’re doing this in our Saturday Life Hacks edition. Here are some tips for getting in far more plants than you might think, a lot more easily than you might think:

- Buy things ready-mixed. This means buying the frozen mixed veg, the frozen mixed chopped fruit, the mixed nuts, the mixed salad greens etc. This way, when you’re reaching for one pack of something, you’re getting 3–5 different plants instead of one.

- Buy things individually, and mix them for storage. This is a more customized version of the above, but in the case of things that keep for at least a while, it can make lazy options a lot more plentiful. Suddenly, instead of rice with your salad you’re having sorghum, millet, buckwheat, and quinoa. This trick also works great for dried berries that can just be tipped into one’s morning oatmeal. Or, you know, millet, oats, rye, and barley. Suddenly, instead of 1 or 2 plants for breakfast you have maybe 7 or 8.

- Keep a well-stocked pantry of shelf-stable items. This is good practice anyway, in case of another supply-lines shutdown like at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. But for plant diversity, it means that if you’re making enchiladas, then instead using kidney beans because that’s what’s in the cupboard, you can raid your pantry for kidney beans, black beans, pinto beans, fava beans, etc etc. Yes, all of them; that’s a list, not a menu.

- Shop in the discount section of the supermarket. You don’t have shop exclusively there, but swing by that area, see what plants are available for next to nothing, and buy at least one of each. Figure out what to do with it later, but the point here is that it’s a good way to get suggestions of plants that you weren’t actively looking for—and novelty is invariably a step into diversity.

- Shop in a different store. You won’t be able to beeline the products you want on autopilot, so you’ll see other things on the way. Also, they may have things your usual store doesn’t.

- Shop in person, not online—at least as often as is practical. This is because when shopping for groceries online, the store will tend to prioritize showing you items you’ve bought before, or similar items to those (i.e. actually the same item, just a different brand). Not good for trying new things!

- Consider a meal kit delivery service. Because unlike online grocery shopping, this kind of delivery service will (usually) provide you with things you wouldn’t normally buy. Our sometimes-sponsor Purple Carrot is a fine option for this, but there are plenty of others too.

- Try new recipes, especially if they have plants you don’t normally use. Make a note of the recipe, and go out of your way to get the ingredients; if it seems like a chore, reframe it as a little adventure instead. Honestly, it’s things like this that keep us young in more ways than just what polyphenols can do!

- Hide the plants. Whether or not you like them; hide them just because it works in culinary terms. By this we mean; blend beans into that meaty sauce; thicken the soup with red lentils, blend cauliflower into the gravy. And so on.

One more “magic 30”, while we’re at it…

30g fiber per day makes a big (positive) difference to many aspects of health. Obviously, plants are where that comes from, so there’s a big degree of overlap here, but most of the tips we gave are different, so for double the effectiveness, check out:

Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

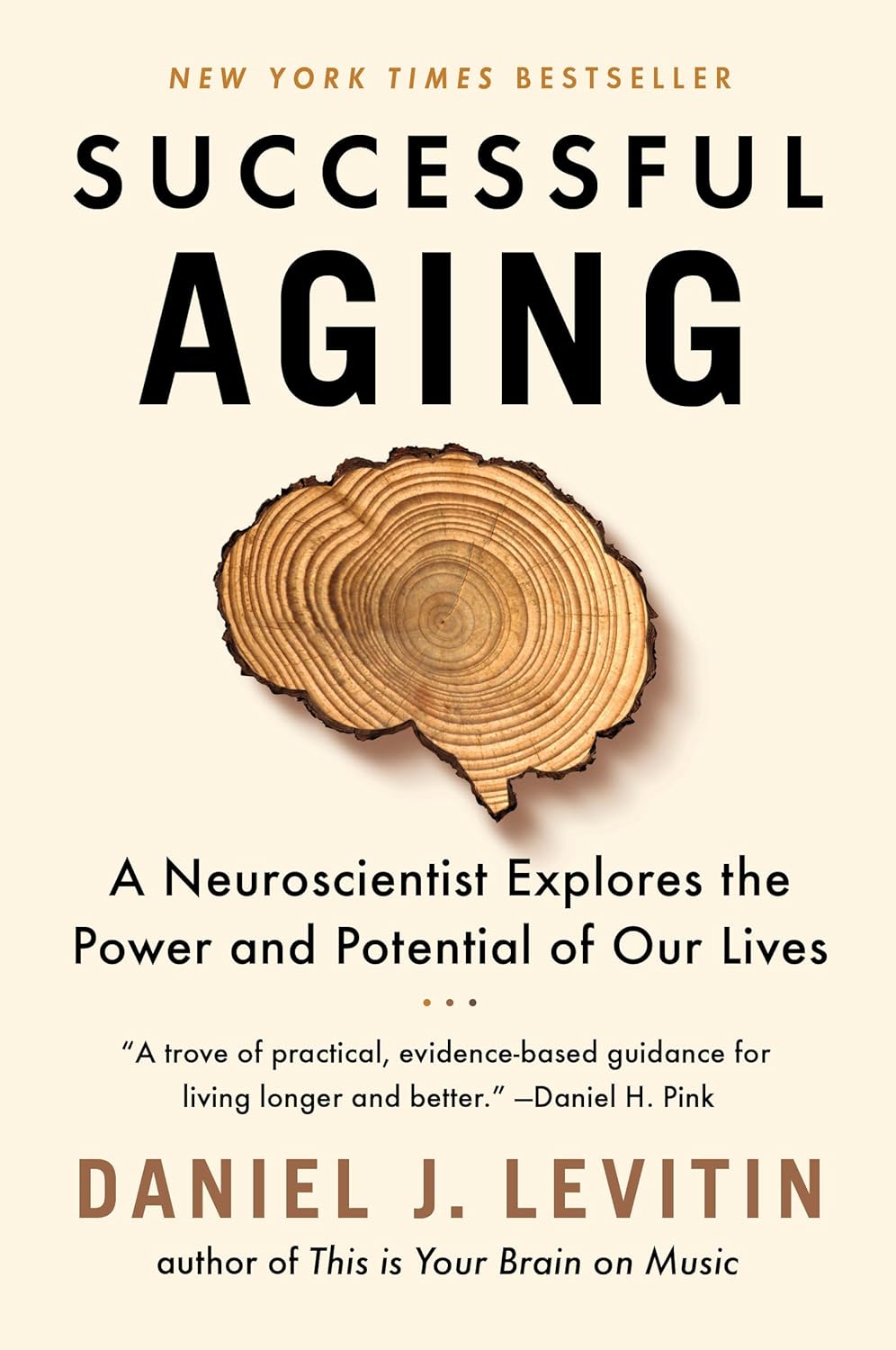

Successful Aging – by Dr. Daniel Levitin

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We all know about age-related cognitive decline. What if there’s a flipside, though?

Neuroscientist Dr. Daniel Levitin explores the changes that the brain undergoes with age, and notes that it’s not all downhill.

From cumulative improvements in the hippocampi to a dialling-down of the (often overfunctioning) amygdalae, there are benefits too.

The book examines the things that shape our brains from childhood into our eighties and beyond. Many milestones may be behind us, but neuroplasticity means there’s always time for rewiring. Yes, it also covers the “how”.

We learn also about the neurogenesis promoted by such simple acts as taking a different route and/or going somewhere new, and what other things improve the brain’s healthspan.

The writing style is very accessible “pop-science”, and is focused on being of practical use to the reader.

Bottom line: if you want to get the most out of your aging wizening brain, this book is a great how-to manual.

Click here to check out Successful Aging and level up your later years!

Share This Post

-

Nicotine pouches are being marketed to young people on social media. But are they safe, or even legal?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Flavoured nicotine pouches are being promoted to young people on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram.

Although some viral videos have been taken down following a series of reports in The Guardian, clips featuring Australian influencers have claimed nicotine pouches are a safe and effective way to quit vaping. A number of the videos have included links to websites selling these products.

With the rapid rise in youth vaping and the subsequent implementation of several reforms to restrict access to vaping products, it’s not entirely surprising the tobacco industry is introducing more products to maintain its future revenue stream.

The major trans-national tobacco companies, including Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco, all manufacture nicotine pouches. British American Tobacco’s brand of nicotine pouches, Velo, is a leading sponsor of the McLaren Formula 1 team.

But what are nicotine pouches, and are they even legal in Australia?

Like snus, but different

Nicotine pouches are available in many countries around the world, and their sales are increasing rapidly, especially among young people.

Nicotine pouches look a bit like small tea bags and are placed between the lip and gum. They’re typically sold in small, colourful tins of about 15 to 20 pouches. While the pouches don’t contain tobacco, they do contain nicotine that is either extracted from tobacco plants or made synthetically. The pouches come in a wide range of strengths.

As well as nicotine, the pouches commonly contain plant fibres (in place of tobacco, plant fibres serve as a filler and give the pouches shape), sweeteners and flavours. Just like for vaping products, there’s a vast array of pouch flavours available including different varieties of fruit, confectionery, spices and drinks.

The range of appealing flavours, as well as the fact they can be used discreetly, may make nicotine pouches particularity attractive to young people.

Vaping has recently been subject to tighter regulation in Australia.

Aleksandr Yu/ShutterstockUsers absorb the nicotine in their mouths and simply replace the pouch when all the nicotine has been absorbed. Tobacco-free nicotine pouches are a relatively recent product, but similar style products that do contain tobacco, known as snus, have been popular in Scandinavian countries, particularly Sweden, for decades.

Snus and nicotine pouches are however different products. And given snus contains tobacco and nicotine pouches don’t, the products are subject to quite different regulations in Australia.

What does the law say?

Pouches that contain tobacco, like snus, have been banned in Australia since 1991, as part of a consumer product ban on all forms of smokeless tobacco products. This means other smokeless tobacco products such as chewing tobacco, snuff, and dissolvable tobacco sticks or tablets, are also banned from sale in Australia.

Tobacco-free nicotine pouches cannot legally be sold by general retailers, like tobacconists and convenience stores, in Australia either. But the reasons for this are more complex.

In Australia, under the Poisons Standard, nicotine is a prescription-only medicine, with two exceptions. Nicotine can be used in tobacco prepared and packed for smoking, such as cigarettes, roll-your-own tobacco, and cigars, as well as in preparations for therapeutic use as a smoking cessation aid, such as nicotine patches, gum, mouth spray and lozenges.

If a nicotine-containing product does not meet either of these two exceptions, it cannot be legally sold by general retailers. No nicotine pouches have currently been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration as a therapeutic aid in smoking cessation, so in short they’re not legal to sell in Australia.

However, nicotine pouches can be legally imported for personal use only if users have a prescription from a medical professional who can assess if the product is appropriate for individual use.

We only have anecdotal reports of nicotine pouch use, not hard data, as these products are very new in Australia. But we do know authorities are increasingly seizing these products from retailers. It’s highly unlikely any young people using nicotine pouches are accessing them through legal channels.

Health concerns

Nicotine exposure may induce effects including dizziness, headache, nausea and abdominal cramps, especially among people who don’t normally smoke or vape.

Although we don’t yet have much evidence on the long term health effects of nicotine pouches, we know nicotine is addictive and harmful to health. For example, it can cause problems in the cardiovascular system (such as heart arrhythmia), particularly at high doses. It may also have negative effects on adolescent brain development.

The nicotine contents of some of the nicotine pouches on the market is alarmingly high. Certain brands offer pouches containing more than 10mg of nicotine, which is similar to a cigarette. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, pouches deliver enough nicotine to induce and sustain nicotine addiction.

Pouches are also being marketed as a product to use when it’s not possible to vape or smoke, such as on a plane. So instead of helping a person quit they may be used in addition to smoking and vaping. And importantly, there’s no clear evidence pouches are an effective smoking or vaping cessation aid.

A Velo product display at Dubai airport in October 2022. Nicotine pouches are marketed as safe to use on planes.

Becky FreemanFurther, some nicotine pouches, despite being tobacco-free, still contain tobacco-specific nitrosamines. These compounds can damage DNA, and with long term exposure, can cause cancer.

Overall, there’s limited data on the harms of nicotine pouches because they’ve been on the market for only a short time. But the WHO recommends a cautious approach given their similarities to smokeless tobacco products.

For anyone wanting advice and support to quit smoking or vaping, it’s best to talk to your doctor or pharmacist, or access trusted sources such as Quitline or the iCanQuit website.

Becky Freeman, Associate Professor, School of Public Health, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Milk Thistle For The Brain, Bones, & More

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Thistle Do Nicely”

Milk thistle is a popular supplement; it comes from the milk thistle plant (Silybum marianum), commonly just called thistles. There are other kinds of thistle too, but these are one of the most common.

So, what does it do?

Liver health

Milk thistle enjoys popular use to support liver health; the liver is a remarkably self-regenerative organ if given the chance, but sometimes it can use a helping hand.

See for example: How To Undo Liver Damage

As for milk thistle’s beneficence, it is very well established:

- Milk thistle in liver diseases: past, present, future

- Hepatoprotective effect of silymarin

- Silybum Marianum and Chronic Liver Disease: A Marriage of Many Years

Brain health

For this one the science is less well-established, as studies so far have been on non-human animals, or have been in vitro studies.

Nevertheless, the results so far are promising, and the mechanism of action seems to be a combination of reducing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, as well as suppressing amyloid β-protein (Aβ) fibril formation, in other words, reducing amyloid plaques.

General overview: A Mini Review on the Chemistry and Neuroprotective Effects of Silymarin

All about the plaques, but these are non-human animal studies:

- Mouse model: Silymarin attenuated the amyloid β plaque burden and improved behavioral abnormalities in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model

- Rat model: Silymarin effect on amyloid-β plaque accumulation and gene expression of APP in an Alzheimer’s disease rat model

Against diabetes

Milk thistle improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces fasting blood sugar levels and HbA1c levels. The research so far is mostly in type 2 diabetes, however (at least, so far as we could find). For example:

Studies we could find for T1D were very far from translatable to human usefulness, for example, “we poisoned these rats with streptozotocin then gave them megadoses of silymarin (10–15 times the dose usually recommended for humans) and found very small benefits to the lenses of their eyes” (source).

Against osteoporosis

In this case, milk thistle’s estrogenic effects may be of merit to those at risk of menopause-induced osteoporosis:

If you’d like a quick primer about such things as what antiosteoclastic activity is, here’s a quick recap:

Which Osteoporosis Medication, If Any, Is Right For You?

Is it safe?

It is “Generally Recognized As Safe”, and even when taken at high doses for long periods, side effects are very rare.

Contraindications include if you’re pregnant, nursing, or allergic.

Potential reasons for caution (but not necessarily contraindication) include if you’re diabetic (its blood-sugar lowering effects will decrease the risk of hyperglycemia while increasing the risk of hypoglycemia), or have a condition that could be exacerbated by its estrogenic effects—including if you are on HRT, because it’s an estrogen receptor agonist in some ways (for example those bone benefits we mentioned before) but an estrogen antagonist in others (for example, in the uterus, if you have one, or in nearby flat muscles, if you don’t).

As ever, speak with your doctor/pharmacist to be sure.

Want to try it?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Is Unnoticed Environmental Mold Harming Your Health?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Environmental mold can be a lot more than just the famously toxic black mold that sometimes makes the headlines, and many kinds you might not notice, but it can colonizes your sinuses and gut just the same:

Breaking the mold

Around 25% of homes in North America are estimated to have mold, though the actual number is likely to be higher, affecting both older and new homes. For that matter, mold can grow in unexpected areas, like inside air conditioning units, even in dry regions.

If mold just sat where it is minding its own business, it might not be so bad, but instead they release their spores, which are de facto airborne mycotoxins, which can colonize places like the sinuses or gut, causing significant health issues.

Not everyone in the same household is affected the same way by mold due to genetic differences and varying pre-existing health conditions. But as a general rule of thumb, mold inflames the brain, nerves, gut, and skin, and can negatively impact the vagal nerve, which is linked to the gut-brain connection. Mycotoxins also damage mitochondria, leading to symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, and cognitive issues. To complicate matters further, mold illness can mimic other conditions like anxiety, chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, IBS, and more, making it difficult to diagnose.

Testing is possible, though they all have limitations, e.g:

- Home testing: testing the home for mold spores and mycotoxins is crucial for effective treatment; professional mold remediation companies are a good idea (to do a thorough job of cleaning, without also breathing in half the mold while cleaning it).

- Mold allergy testing: mold allergy testing (IgE testing or skin tests) is often used, but it doesn’t diagnose mold-related illnesses linked to severe symptoms like fatigue or neurodegeneration.

- Serum antibody testing: tests for immune reactions (IgG) to mycotoxins may not always show positive results if the immune system is weakened by long-term exposure.

- Urine mycotoxin testing: urine tests can detect mycotoxins in the body, though are likely to be more expensive, being probably not covered by public health in Canada or insurance in the US.

- Organic acid testing: this urine test can indicate mold colonization in areas like the sinuses or gut. Again, cost/availability may vary, though.

For more information on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

7 Principles of Becoming a Leader – by Riku Vuorenmaa

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We urge you to overlook the cliché cover art (we don’t know what they were thinking, going for the headless suited torso) because…

This one could be the best investment you make in your career this year! You may be wondering what the titular 7 principles are. We won’t keep you guessing; they are:

- Professional development: personal excellence, productivity, and time management

- Leadership development: mindset and essential leadership skills

- Personal development: your motivation, character, and confidence as a leader

- Career management: plan your career, get promoted and paid well

- Social skills & networking: work and connect with the right people

- Business- & company-understanding: the big picture

- Commitment: make the decision and commit to becoming a great leader

A lot of leadership books repeat the same old fluff that we’ve all read many times before… padded with a lot of lengthy personal anecdotes and generally editorializing fluff. Not so here!

While yes, this book does also cover some foundational things first, it’d be remiss not to. It also covers a whole (much deeper) range of related skills, with down-to-earth, brass tacks advice on putting them into practice.

This is the kind of book you will want to set as a recurring reminder in your phone, to re-read once a year, or whatever schedule seems sensible to you.

There aren’t many books we’d put in that category!

Pick Up Your Copy of the “7 Principles of Becoming a Leader” on Amazon Today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: