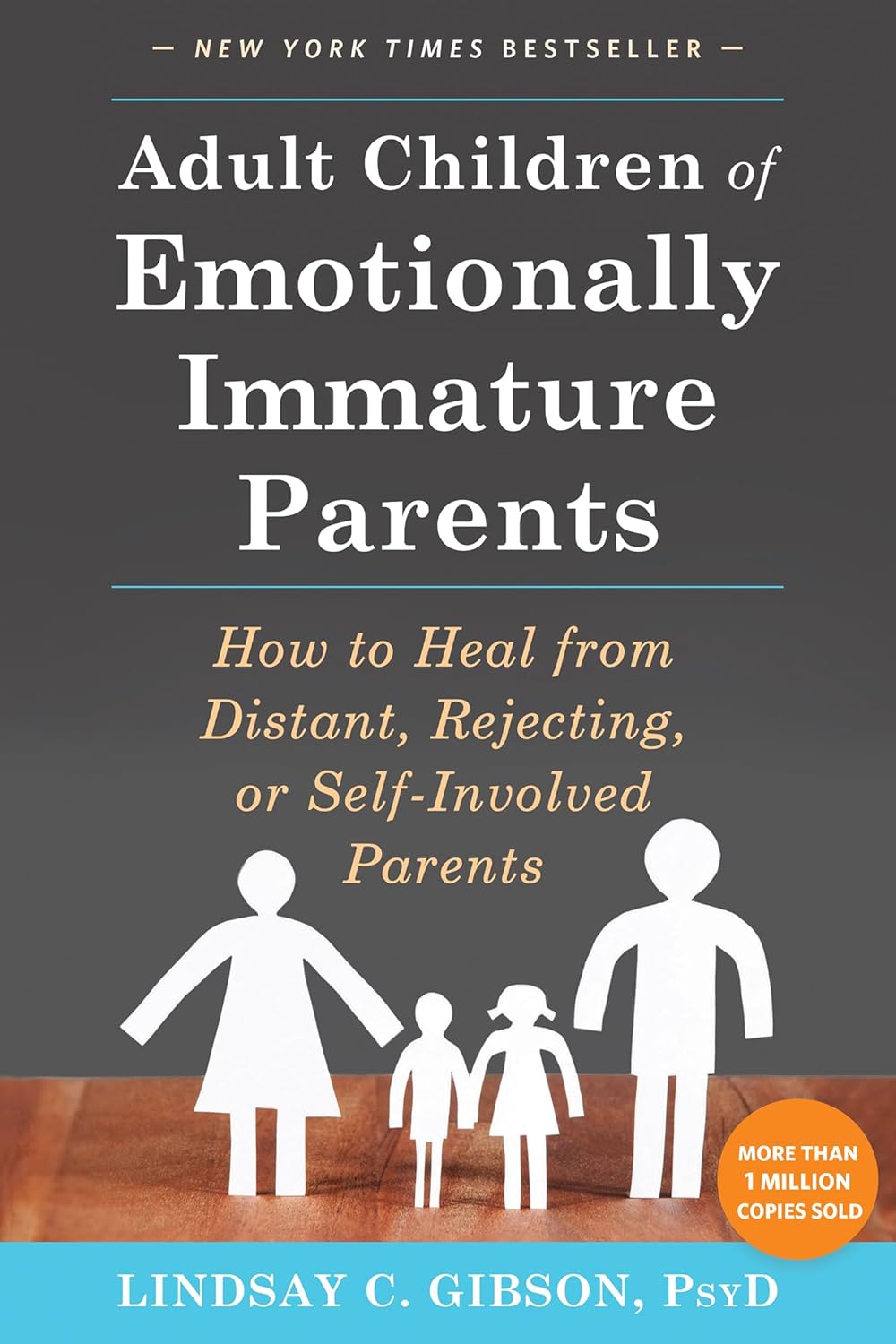

Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents – by Dr. Lindsay Gibson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Not everyone had the best of parents, and the harm done can last well beyond childhood. This book looks at healing that.

Dr. Gibson talks about four main kinds of “difficult” parents, though of course they can overlap:

- The emotional parent, with their unpredictable outbursts

- The driven parent, with their projected perfectionism

- The passive parent, with their disinterest and unreliability

- The rejecting parent, with their unavailability and insults

For all of them, it’s common that nothing we could do was ever good enough, and that leaves a deep scar. To add to it, the unfavorable dynamic often persists in adult life, assuming everyone involved is still alive and in contact.

So, what to do about it? Dr. Gibson advocates for first getting a good understanding of what wasn’t right/normal/healthy, because it’s easy for a lot of us to normalize the only thing we’ve ever known. Then, beyond merely noting that no child deserved that lack of compassion, moving on to pick up the broken pieces one by one, and address each in turn.

The style of the book is anecdote-heavy (case studies, either anonymized or synthesized per common patterns) in a way that will probably be all-too-relatable to a lot of readers (assuming that if you buy this book, it’s for a reason), science-moderate (references peppered into the text; three pages of bibliography), and practicality-dense—that is to say, there are lots of clear usable examples, there are self-assessment questionnaires, there are worksheets for now making progress forward, and so forth.

Bottom line: if one or more of the parent types above strikes a chord with you, there’s a good chance you could benefit from this book.

Click here to check out Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents, and rebuild yourself!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

ADHD medication – can you take it long term? What are the risks and do benefits continue?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a condition that can affect all stages of life. Medication is not the only treatment, but it is often the treatment that can make the most obvious difference to a person who has difficulties focusing attention, sitting still or not acting on impulse.

But what happens once you’ve found the medication that works for you or your child? Do you just keep taking it forever? Here’s what to consider.

What are ADHD medications?

The mainstay of medication for ADHD is stimulants. These include methylphenidate (with brand names Ritalin, Concerta) and dexamfetamine. There is also lisdexamfetamine (branded Vyvanse), a “prodrug” of dexamfetamine (it has a protein molecule attached, which is removed in the body to release dexamfetamine).

There are also non-stimulants, in particular atomoxetine and guanfacine, which are used less often but can also be highly effective. Non-stimulants can be prescribed by GPs but this may not always be covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and could cost more.

How stimulants work

Some stimulants prescribed for ADHD are “short acting”. This means the effect comes on after around 20 minutes and lasts around four hours.

Longer-acting stimulants give a longer-lasting effect, usually by releasing medication more slowly. The choice between the two will be guided by whether the person wants to take medication once a day or prefers to target the medication effect to specific times or tasks.

For the stimulants (with the possible exception of lisdexamfetamine) there is very little carry-over effect to the next day. This means the symptoms of ADHD may be very obvious until the first dose of the morning takes effect.

One of the main aims of treatment is the person with ADHD should live their best life and achieve their goals. In young children it is the parents who have to consider the risks and benefits on behalf of the child. As children mature, their role in decision making increases.

What about side effects?

The most consistent side effects of the stimulants are they suppress appetite, resulting in weight loss. In children this is associated with temporary slowing of the growth rate and perhaps a slight delay in pubertal development. They can also increase the heart rate and may cause a rise in blood pressure. Stimulants often cause insomnia.

These changes are largely reversible on stopping medication. However, there is concern the small rises in blood pressure could accelerate the rate of heart disease, so people who take medication over a number of years might have heart attacks or strokes slightly sooner than would have happened otherwise.

This does not mean older adults should not have their ADHD treated. Rather, they should be aware of the potential risks so they can make an informed decision. They should also make sure high blood pressure and attacks of chest pain are taken seriously.

Stimulants can be associated with stomach ache or headache. These effects may lessen over time or with a reduction in dose. While there have been reports about stimulants being misused by students, research on the risks of long-term prescription stimulant dependence is lacking.

Will medication be needed long term?

Although ADHD can affect a person’s functioning at all stages of their life, most people stop medication within the first two years.

People may stop taking it because they don’t like the way it makes them feel, or don’t like taking medication at all. Their short period on medication may have helped them develop a better understanding of themselves and how best to manage their ADHD.

In teenagers the medication may lose its effectiveness as they outgrow their dose and so they stop taking it. But this should be differentiated from tolerance, when the dose becomes less effective and there are only temporary improvements with dose increases.

Tolerance may be managed by taking short breaks from medication, switching from one stimulant to another or using a non-stimulant.

Medication is usually prescribed by a specialist but rules differ around Australia.

Ground Picture/ShutterstockToo many prescriptions?

ADHD is becoming increasingly recognised, with more people – 2–5% of adults and 5–10% of children – being diagnosed. In Australia stimulants are highly regulated and mainly prescribed by specialists (paediatricians or psychiatrists), though this differs from state to state. As case loads grow for this lifelong diagnosis, there just aren’t enough specialists to fit everyone in.

In November, a Senate inquiry report into ADHD assessment and support services highlighted the desperation experienced by people seeking treatment.

There have already been changes to the legislation in New South Wales that may lead to more GPs being able to treat ADHD. Further training could help GPs feel more confident to manage ADHD. This could be in a shared-care arrangement or independent management of ADHD by GPs like a model being piloted at Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District, with GPs training within an ADHD clinic (where I am a specialist clinician).

Not every person with ADHD will need or want to take medication. However, it should be more easily available for those who could find it helpful.

Alison Poulton, Senior Lecturer, Brain Mind Centre Nepean, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

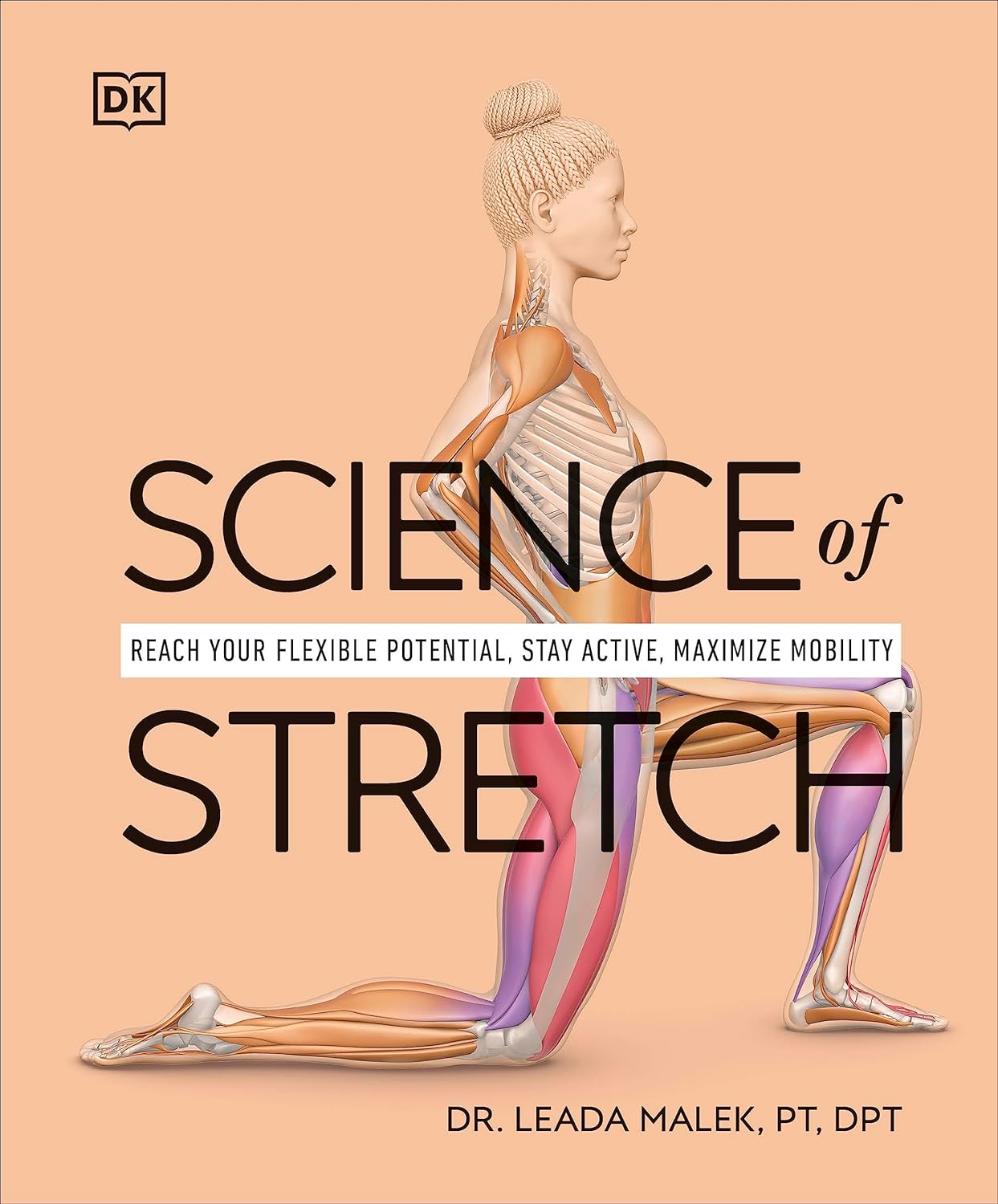

Science of Stretch – by Dr. Leada Malek

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book is part of a “Science of…” series, of which we’ve reviewed some others before (Yoga | HIIT | Pilates), and needless to say, we like them.

You may be wondering: is this just that thing where a brand releases the same content under multiple names to get more sales, and no, it’s not (long-time 10almonds readers will know: if it were, we’d say so!).

While flexibility and mobility are indeed key benefits in yoga and Pilates, they looked into the science of what was going on in yoga asanas and Pilates exercises, stretchy or otherwise, so the stretching element was not nearly so deep as in this book.

In this one, Dr. Malek takes us on a wonderful tour of (relevant) human anatomy and physiology, far deeper than most pop-science books go into when it comes to stretching, so that the reader can really understand every aspect of what’s going on in there.

This is important, because it means busting a lot of myths (instead of busting tendons and ligaments and things), understanding why certain things work and (critically!) why certain things don’t, how certain stretching practices will sabotage our progress, things like that.

It’s also beautifully clearly illustrated! The cover art is a fair representation of the illustrations inside.

Bottom line: if you want to get serious about stretching, this is a top-tier book and you won’t regret it.

Click here to check out Science of Stretching, and learn what you can do and how!

Share This Post

-

Boundary-Setting Beyond “No”

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

More Than A “No”

A lot of people struggle with boundary-setting, and it’s not always the way you might think.

The person who “can’t say no” to people probably comes to mind, but the problem is more far-reaching than that, and it’s rooted in not being clear over what a boundary actually is.

For example: “Don’t bring him here again!”

Pretty clear, right?

And while it is indeed clear, it’s not a boundary; it’s a command. Which may or may not be obeyed, and at the end of the day, what right have we to command people in general?

Same goes for less dramatic things like “Don’t talk to me about xyz”, which can still be important or trivial, depending on whether the topic of xyz is deeply traumatizing for you, or mildly annoying, or something else entirely.

Why this becomes a problem

It becomes a problem not because of any lack of clarity about your wishes, but rather, because it opens the floor for a debate. The listener may be given to wonder whether your right to not experience xyz is greater or lesser than their right to do/say/etc xyz.

“My right to swing my fist ends where someone else’s nose begins”

…does not help here, firstly because both sides will believe themself (or nobody) to be the injured party; for the fist-swinger, the other person’s nose made a vicious assault on their freedom. Or secondly, maybe there was some higher principle at stake; a reason why violence was justified. And then ten levels of philosophical debate. We see this a lot when it comes to freedom of expression, and vigorous debate over whether this entails freedom from social consequences of one’s words/actions.

How a good boundary-setting works (if this, then that)

Consider two signs:

- No trespassing!

- Trespassers will be shot!

Superficially, the second just seems like a more violent rendition of the first. But in fact, the second is more informationally useful: it explains what will happen if the boundary is not respected, and allows the reader to make their own informed decision with regard to what to do with that information.

We can employ this method (and can even do so gently, if we so wish and hopefully we mostly do wish to be gentle) when it comes to social and interpersonal boundary-setting:

- If you bring him here again, I will refuse you entrance

- If you bring up that topic again, I will ask you to leave

- If you do that, I will never speak to you again

- If you don’t stop drinking, I will divorce you

This “if-this-then-that” model does the very first thing that any good boundary does: make itself clear.

It doesn’t rely on moral arguments; it doesn’t invite debate. For example in that last case, it doesn’t argue that the partner doesn’t have the right to drink—it simply expresses what the speaker will exercise their own right to do, in that eventuality.

(as an aside, the situation that occurs when one is enmeshed with someone who is dependent on a substance is a complex topic, and if you’re interested in that, check out: Codependency Isn’t What Most People Think)

Back on track: boundary-setting is not about what’s right or good—it’s about nothing more nor less than a clear delineation between what we will and won’t accept, and how we’ll enforce that.

We can also, in particularly personal boundary-setting (such as with sexual boundaries’ oft-claimed “gray areas”), fix an improperly-set boundary that forgot to do the above, e.g:

“How about [proposition]?”

“No thank you” ← casually worded answer; contextually reasonable, and yet not a clear boundary per what we discussed above

“Come on, I think you’d like it”

“I said no. No means no. Ask me again and I will [consequences that are appropriate and actionable]”What’s “appropriate and actionable” may vary a lot from one situation to another, but it’s important that it’s something you can do and are prepared to do and will do if the condition for doing it is met.

Anything less than that is not a boundary—it’s just a request.

Note: this does not require that we have power, by the way. If we have zero power in a situation, well, that definitely sucks, but even then we can still express what is actionable, e.g. “I will never trust you again”.

“Price of entry”

You may have wondered, upon reading “boundary-setting is not about what’s right or good—it’s about nothing more nor less than a clear delineation between what we will and won’t accept, and how we’ll enforce that”, can’t that be used to control and manipulate people, essentially coercing them to do or not do things with the threat of consequences (specifically: bad ones)?

And the answer is: yes, yes it can.

But that’s where the flipside comes into play—the other person gets to set their boundaries, too.

For all of us, if we have any boundaries at all, there is a “price of entry” and all who want to be in our lives, or be close to us, have to decide for themselves whether that price of entry is worth it.

- If a person says “do not talk about topic xyz to me or I will leave”, that is a price of entry for being close to them.

- If you are passionate about talking about topic xyz to the point that you are unwilling to shelve it when in their presence, then that is the price of entry for being close to you.

- If one or more of you is not willing to pay the price of entry, then guess what, you’re just not going to be close.

In cases of forced proximity (e.g. workplaces or families) this is likely to get resolved by the workplace’s own rules (i.e. the price of entry that you agreed to when signing a contract to work there), and if something like that doesn’t exist (such as in families), well, that forced proximity is going to reach a breaking point, and somebody may discover it wasn’t enforceable after all.

See also: Family Estrangement: More Common Than Most People Think

…which also details how to fix it, where possible.

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

War in Ukraine affected wellbeing worldwide, but people’s speed of recovery depended on their personality

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The war in Ukraine has had impacts around the world. Supply chains have been disrupted, the cost of living has soared and we’ve seen the fastest-growing refugee crisis since World War II. All of these are in addition to the devastating humanitarian and economic impacts within Ukraine.

Our international team was conducting a global study on wellbeing in the lead up to and after the Russian invasion. This provided a unique opportunity to examine the psychological impact of the outbreak of war.

As we explain in a new study published in Nature Communications, we learned the toll on people’s wellbeing was evident across nations, not just in Ukraine. These effects appear to have been temporary – at least for the average person.

But people with certain psychological vulnerabilities struggled to recover from the shock of the war.

Tracking wellbeing during the outbreak of war

People who took part in our study completed a rigorous “experience-sampling” protocol. Specifically, we asked them to report their momentary wellbeing four times per day for a whole month.

Data collection began in October 2021 and continued throughout 2022. So we had been tracking wellbeing around the world during the weeks surrounding the outbreak of war in February 2022.

We also collected measures of personality, along with various sociodemographic variables (including age, gender, political views). This enabled us to assess whether different people responded differently to the crisis. We could also compare these effects across countries.

Our analyses focused primarily on 1,341 participants living in 17 European countries, excluding Ukraine itself (44,894 experience-sampling reports in total). We also expanded these analyses to capture the experiences of 1,735 people living in 43 countries around the world (54,851 experience-sampling reports) – including in Australia.

A global dip in wellbeing

On February 24 2022, the day Russia invaded Ukraine, there was a sharp decline in wellbeing around the world. There was no decline in the month leading up to the outbreak of war, suggesting the change in wellbeing was not already occurring for some other reason.

However, there was a gradual increase in wellbeing during the month after the Russian invasion, suggestive of a “return to baseline” effect. Such effects are commonly reported in psychological research: situations and events that impact our wellbeing often (though not always) do so temporarily.

Unsurprisingly, people in Europe experienced a sharper dip in wellbeing compared to people living elsewhere around the world. Presumably the war was much more salient for those closest to the conflict, compared to those living on an entirely different continent.

Interestingly, day-to-day fluctuations in wellbeing mirrored the salience of the war on social media as events unfolded. Specifically, wellbeing was lower on days when there were more tweets mentioning Ukraine on Twitter/X.

Our results indicate that, on average, it took around two months for people to return to their baseline levels of wellbeing after the invasion.

Different people, different recoveries

There are strong links between our wellbeing and our individual personalities.

However, the dip in wellbeing following the Russian invasion was fairly uniform across individuals. None of the individual factors assessed in our study, including personality and sociodemographic factors, predicted people’s response to the outbreak of war.

On the other hand, personality did play a role in how quickly people recovered. Individual differences in people’s recovery were linked to a personality trait called “stability”. Stability is a broad dimension of personality that combines low neuroticism with high agreeableness and conscientiousness (three traits from the Big Five personality framework).

Stability is so named because it reflects the stability of one’s overall psychological functioning. This can be illustrated by breaking stability down into its three components:

- low neuroticism describes emotional stability. People low in this trait experience less intense negative emotions such as anxiety, fear or anger, in response to negative events

- high agreeableness describes social stability. People high in this trait are generally more cooperative, kind, and motivated to maintain social harmony

- high conscientiousness describes motivational stability. People high in this trait show more effective patterns of goal-directed self-regulation.

So, our data show that people with less stable personalities fared worse in terms of recovering from the impact the war in Ukraine had on wellbeing.

In a supplementary analysis, we found the effect of stability was driven specifically by neuroticism and agreeableness. The fact that people higher in neuroticism recovered more slowly accords with a wealth of research linking this trait with coping difficulties and poor mental health.

These effects of personality on recovery were stronger than those of sociodemographic factors, such as age, gender or political views, which were not statistically significant.

Overall, our findings suggest that people with certain psychological vulnerabilities will often struggle to recover from the shock of global events such as the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

Luke Smillie, Professor in Personality Psychology, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

8 Signs Of High Cortisol & How To Reverse “Cortisol Face”

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Shereene Idriss has insights about the facial features that might indicate chronically elevated cortisol levels, and what to do about same:

At face value

Dr. Idriss notes that for most people, this should not be cause for undue concern, although hypercortisolism can also be associated with genetic disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome, as well as prolonged use of certain medication, or the presence of certain tumors. As well as facial swelling, hypercortisolism can also result in other physical changes like acne, weight gain, skin thinning, stretch marks, infections, and hair loss.

As for what to do about it, she recommends addressing lifestyle factors like poor sleep, unhealthy diet, alcohol consumption, and lack of hydration to reduce facial puffiness related to stress. Diet suggestions include incorporating foods rich in magnesium, vitamin C, and omega-3s, such as leafy greens, fatty fish, nuts and seeds, and berries.

She also suggests some supplements to consider, such as ashwagandha, magnesium, omega-3s, and/or l-theanine, but you might want to speak to your doctor/pharmacist to check in case of contraindications per any other conditions you may have, or medications you may be on.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

- Ashwagandha: The Root of All Even-Mindedness?

- L-Theanine: What’s The Tea?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Vaping: A Lot Of Hot Air?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Vaping: A Lot Of Hot Air?

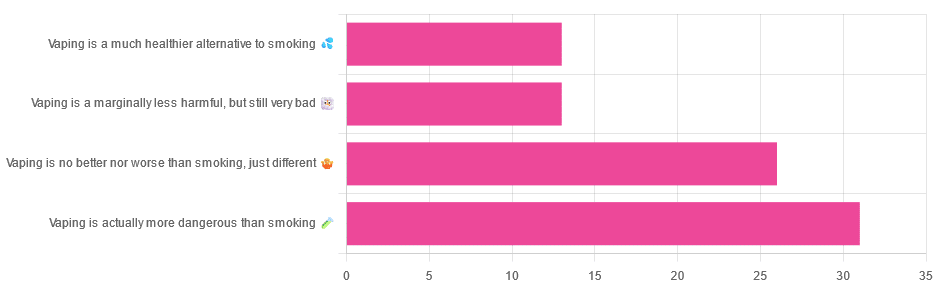

Yesterday, we asked you for your (health-related) opinions on vaping, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- A little over a third of respondents said it’s actually more dangerous than smoking

- A little under a third of respondents said it’s no better nor worse, just different

- A little over 10% of respondents said it’s marginally less harmful, but still very bad

- A little over 10% of respondents said it’s a much healthier alternative to smoking

So what does the science say?

Vaping is basically just steam inhalation, plus the active ingredient of your choice (e.g. nicotine, CBD, THC, etc): True or False?

False! There really are a lot of other chemicals in there.

And “chemicals” per se does not necessarily mean evil green glowing substances that a comicbook villain would market, but there are some unpleasantries in there too:

- Potential harmful health effects of inhaling nicotine-free shisha-pen vapor: a chemical risk assessment of the main components propylene glycol and glycerol

- Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses Induced by Exposure to Commonly Used e-Cigarette Flavoring Chemicals and Flavored e-Liquids without Nicotine

So, the substrate itself can cause irritation, and flavorings (with cinnamaldehyde, the cinnamon flavoring, being one of the worst) can really mess with our body’s inflammatory and oxidative responses.

Vaping can cause “popcorn lung”: True or False?

True and False! Popcorn lung is so-called after it came to attention when workers at a popcorn factory came down with it, due to exposure to diacetyl, a chemical used there.

That chemical was at that time also found in most vapes, but has since been banned in many places, including the US, Canada, the EU and the UK.

Vaping is just as bad as smoking: True or False?

False, per se. In fact, it’s recommended as a means of quitting smoking, by the UK’s famously thrifty NHS, that absolutely does not want people to be sick because that costs money:

Of course, the active ingredients (e.g. nicotine, in the assumed case above) will still be the same, mg for mg, as they are for smoking.

Vaping is causing a health crisis amongst “kids nowadays”: True or False?

True—it just happens to be less serious on a case-by-case basis to the risks of smoking.

However, it is worth noting that the perceived harmlessness of vapes is surely a contributing factor in their widespread use amongst young people—decades after actual smoking (thankfully) went out of fashion.

On the other hand, there’s a flipside to this:

Flavored vape restrictions lead to higher cigarette sales

So, it may indeed be the case of “the lesser of two evils”.

Want to know more?

For a more in-depth science-ful exploration than we have room for here…

BMJ | Impact of vaping on respiratory health

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: