Ginger Does A Lot More Than You Think

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ginger’s benefits go deep!

You are doubtlessly already familiar with what ginger is, so let’s skip right into the science.

The most relevant active compound in the ginger root is called gingerol, and people enjoy it not just for its taste, but also a stack of health reasons, such as:

- For weight loss

- Against nausea

- Against inflammation

- For cardiovascular health

- Against neurodegeneration

Quite a collection! So, what does the science say?

For weight loss

This one’s quite straightforward. It not only helps overall weight loss, but also specifically improves waist-hip ratio, which is a much more important indicator of health than BMI.

Against nausea & pain

Ginger has proven its effectiveness in many high quality clinical trials, against general nausea, post-surgery nausea, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and pregnancy-related nausea.

Source: Ginger on Human Health: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of 109 Randomized Controlled Trials

However! While it very clearly has been shown to be beneficial in the majority of cases, there are some small studies that suggest it may not be safe to take close to the time of giving birth, or in people with a history of pregnancy loss, or unusual vaginal bleeding, or clotting disorders.

See specifically: Ginger for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy

As a side note on the topic of “trouble down there”, ginger has also been found to be as effective as Novafen (a combination drug of acetaminophen (Tylenol), caffeine, and ibuprofen), in the task of relieving menstrual pain:

See: Effect of Ginger and Novafen on menstrual pain: A cross-over trial

Against inflammation & pain

Ginger has well-established anti-inflammatory (and, incidentally, which affects many of the same systems, antioxidant) effects. Let’s take a look at that first:

Read: Effect of Ginger on Inflammatory Diseases

Attentive readers will note that this means that ginger is not merely some nebulous anti-inflammatory agent. Rather, it also specifically helps alleviate delineable inflammatory diseases, ranging from colitis to Crohn’s, arthritis to lupus.

We’ll be honest (we always are!), the benefits in this case are not necessarily life-changing, but they are a statistically significant improvement, and if you are living with one of those conditions, chances are you’ll be glad of even things described in scientific literature as “modestly efficacious”.

What does “modestly efficacious” look like? Here are the numbers from a review of 593 patients’ results in clinical trials (against placebo):

❝Following ginger intake, a statistically significant pain reduction SMD = −0.30 ([95% CI: [(−0.50, −0.09)], P = 0.005]) with a low degree of inconsistency among trials (I2 = 27%), and a statistically significant reduction in disability SMD = −0.22 ([95% CI: ([−0.39, −0.04)]; P = 0.01; I2 = 0%]) were seen, both in favor of ginger.❞

To de-mathify that:

- Ginger reduced pain by 30%

- Ginger reduced disability by 22%

Read the source: Efficacy and safety of ginger in osteoarthritis patients: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials

Because (in part) of the same signalling pathways, it also has benefits against cancer (and you’ll remember, it also reduces the symptoms of chemotherapy).

See for example: Ginger’s Role in Prevention and Treatment of Gastrointestinal Cancer

For cardiovascular health

In this case, its benefits are mostly twofold:

- It significantly reduces triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, while increasing HDL cholesterol

- It significantly reduces fasting blood sugar levels and HbA1c levels (both risk factors for CVD)

Against neurodegeneration

This is in large part because it reduces inflammation, which we discussed earlier.

But, not everything passes the blood-brain barrier, so it’s worth noting when something (like gingerol) does also have an effect on brain health as well as the rest of the body.

You do not want inflammation in your brain; that is Bad™ and strongly associated with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

As well as reducing neuroinflammation, ginger has other relevant mechanisms too:

❝Its bioactive compounds may improve neurological symptoms and pathological conditions by modulating cell death or cell survival signaling molecules.

The cognitive enhancing effects of ginger might be partly explained via alteration of both the monoamine and the cholinergic systems in various brain areas.

Moreover, ginger decreases the production of inflammatory related factors❞

Check it out in full, as this is quite interesting:

Role of Ginger in the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases

How much to take?

In most studies, doses of 1–3 grams/day were used.

Where to get it?

Your local supermarket, as a first port-of-call. Especially given the dose you want, it may be nicer for you to have a touch of sliced ginger root in your cooking, rather than taking 2–6 capsules per day to get the same dose.

Obviously, this depends on your culinary preferences, and ginger certainly doesn’t go with everything!

If you do want it as a supplement, here is an example product on Amazon, for your convenience.

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

From straight to curly, thick to thin: here’s how hormones and chemotherapy can change your hair

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Head hair comes in many colours, shapes and sizes, and hairstyles are often an expression of personal style or cultural identity.

Many different genes determine our hair texture, thickness and colour. But some people’s hair changes around the time of puberty, pregnancy or after chemotherapy.

So, what can cause hair to become curlier, thicker, thinner or grey?

Curly or straight? How hair follicle shape plays a role

Hair is made of keratin, a strong and insoluble protein. Each hair strand grows from its own hair follicle that extends deep into the skin.

Curly hair forms due to asymmetry of both the hair follicle and the keratin in the hair.

Follicles that produce curly hair are asymmetrical and curved and lie at an angle to the surface of the skin. This kinks the hair as it first grows.

The asymmetry of the hair follicle also causes the keratin to bunch up on one side of the hair strand. This pulls parts of the hair strand closer together into a curl, which maintains the curl as the hair continues to grow.

Follicles that are symmetrical, round and perpendicular to the skin surface produce straight hair.

Each hair strand grows from its own hair follicle.

Mosterpiece/ShutterstockLife changes, hair changes

Our hair undergoes repeated cycles throughout life, with different stages of growth and loss.

Each hair follicle contains stem cells, which multiply and grow into a hair strand.

Head hairs spend most of their time in the growth phase, which can last for several years. This is why head hair can grow so long.

Let’s look at the life of a single hair strand. After the growth phase is a transitional phase of about two weeks, where the hair strand stops growing. This is followed by a resting phase where the hair remains in the follicle for a few months before it naturally falls out.

The hair follicle remains in the skin and the stems cells grow a new hair to repeat the cycle.

Each hair on the scalp is replaced every three to five years.

Each hair on the scalp is replaced every three to five years.

Just Life/ShutterstockHormone changes during and after pregnancy alter the usual hair cycle

Many women notice their hair is thicker during pregnancy.

During pregnancy, high levels of oestrogen, progesterone and prolactin prolong the resting phase of the hair cycle. This means the hair stays in the hair follicle for longer, with less hair loss.

A drop in hormones a few months after delivery causes increased hair loss. This is due to all the hairs that remained in the resting phase during pregnancy falling out in a fairly synchronised way.

Hair can change around puberty, pregnancy or after chemotherapy

This is related to the genetics of hair shape, which is an example of incomplete dominance.

Incomplete dominance is when there is a middle version of a trait. For hair, we have curly hair and straight hair genes. But when someone has one curly hair gene and one straight hair gene, they can have wavy hair.

Hormonal changes that occur around puberty and pregnancy can affect the function of genes. This can cause the curly hair gene of someone with wavy hair to become more active. This can change their hair from wavy to curly.

Researchers have identified that activating specific genes can change hair in pigs from straight to curly.

Chemotherapy has very visible effects on hair. Chemotherapy kills rapidly dividing cells, including hair follicles, which causes hair loss. Chemotherapy can also have genetic effects that influence hair follicle shape. This can cause hair to regrow with a different shape for the first few cycles of hair regrowth.

Your hair can change at different stages of your life.

Igor Ivakhno/ShutterstockHormonal changes as we age also affect our hair

Throughout life, thyroid hormones are essential for production of keratin. Low levels of thyroid hormones can cause dry and brittle hair.

Oestrogen and androgens also regulate hair growth and loss, particularly as we age.

Balding in males is due to higher levels of androgens. In particular, high dihydrotestosterone (sometimes shortened to DHT), which is produced in the body from testosterone, has a role in male pattern baldness.

Some women experience female pattern hair loss. This is caused by a combination of genetic factors plus lower levels of oestrogen and higher androgens after menopause. The hair follicles become smaller and smaller until they no longer produce hairs.

Reduced function of the cells that produce melanin (the pigment that gives our hair colour) is what causes greying.

Theresa Larkin, Associate professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Retrain Your Brain – by Dr. Seth Gillihan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

15-Minute Arabic”, “Sharpen Your Chess Tactics in 24 Hours”, “Change Your Life in 7 Days”, “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 weeks”—all real books from this reviewer’s shelves.

The thing with books with these sorts of time periods in the titles is that the time period in the title often bears little relation to how long it takes to get through the book. So what’s the case here?

You’ll probably get through it in more like 7 days, but the pacing is more important than the pace. By that we mean:

Dr. Gillihan starts by assuming the reader is at best “in a rut”, and needs to first pick a direction to head in (the first “week”) and then start getting one’s life on track (the second “week”).

He then gives us, one by one, an array of tools and power-ups to do increasingly better. These tools aren’t just CBT, though of course that features prominently. There’s also mindfulness exercises, and holistic / somatic therapy too, for a real “bringing it all together” feel.

And that’s where this book excels—at no point is the reader left adrift with potential stumbling-blocks left unexamined. It’s a “whole course”.

Bottom line: whether it takes you 7 hours or 7 months, “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 Weeks” is a CBT-and-more course for people who like courses to work through. It’ll get you where you’re going… Wherever you want that to be for you!

Share This Post

-

The Paleo Diet

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s The Real Deal With The Paleo Diet?

The Paleo diet is popular, and has some compelling arguments for it.

Detractors, meanwhile, have derided Paleo’s inclusion of modern innovations, and have also claimed it’s bad for the heart.

But where does the science stand?

First: what is it?

The Paleo diet looks to recreate the diet of the Paleolithic era—in terms of nutrients, anyway. So for example, you’re perfectly welcome to use modern cooking techniques and enjoy foods that aren’t from your immediate locale. Just, not foods that weren’t a thing yet. To give a general idea:

Paleo includes:

- Meat and animal fats

- Eggs

- Fruits and vegetables

- Nuts and seeds

- Herbs and spices

Paleo excludes:

- Processed foods

- Dairy products

- Refined sugar

- Grains of any kind

- Legumes, including any beans or peas

Enjoyers of the Mediterranean Diet or the DASH heart-healthy diet, or those with a keen interest in nutritional science in general, may notice they went off a bit with those last couple of items at the end there, by excluding things that scientific consensus holds should be making up a substantial portion of our daily diet.

But let’s break it down…

First thing: is it accurate?

Well, aside from the modern cooking techniques, the global market of goods, and the fact it does include food that didn’t exist yet (most fruits and vegetables in their modern form are the result of agricultural engineering a mere few thousand years ago, especially in the Americas)…

…no, no it isn’t. Best current scientific consensus is that in the Paleolithic we ate mostly plants, with about 3% of our diet coming from animal-based foods. Much like most modern apes.

Ok, so it’s not historically accurate. No biggie, we’re pragmatists. Is it healthy, though?

Well, health involves a lot of factors, so that depends on what you have in mind. But for example, it can be good for weight loss, almost certainly because of cutting out refined sugar and, by virtue of cutting out all grains, that means having cut out refined flour products, too:

Diet Review: Paleo Diet for Weight Loss

Measured head-to-head with the Mediterranean diet for all-cause mortality and specific mortality, it performed better than the control (Standard American Diet, or “SAD”), probably for the same reasons we just mentioned. However, it was outperformed by the Mediterranean Diet:

So in lay terms: the Paleo is definitely better than just eating lots of refined foods and sugar and stuff, but it’s still not as good as the Mediterranean Diet.

What about some of the health risk claims? Are they true or false?

A common knee-jerk criticism of the paleo-diet is that it’s heart-unhealthy. So much red meat, saturated fat, and no grains and legumes.

The science agrees.

For example, a recent study on long-term adherence to the Paleo diet concluded:

❝Results indicate long-term adherence is associated with different gut microbiota and increased serum trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a gut-derived metabolite associated with cardiovascular disease. A variety of fiber components, including whole grain sources may be required to maintain gut and cardiovascular health.❞

Bottom line:

The Paleo Diet is an interesting concept, and certainly can be good for short-term weight loss. In the long-term, however (and: especially for our heart health) we need less meat and more grains and legumes.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Steps For Keeping Your Feet A Healthy Foundation

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Important Steps For Good Health

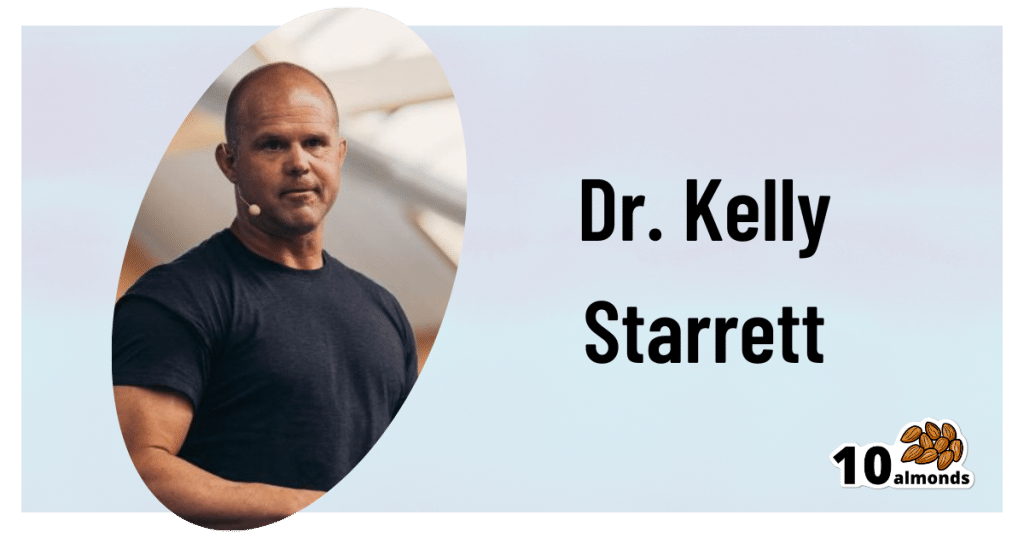

This is Dr. Kelly Starrett. He’s a physiotherapist, author, speaker, trainer. He has been described as a “celebrity” and “founding father” of CrossFit. He mostly speaks and writes about mobility in general; today we’re going to be looking at what he has to say specifically about our feet.

A strong foundation

“An army marches on its stomach”, Napoleon famously wrote.

More prosaically: an army marches on its feet, and good foot-care is a top priority for soldiers—indeed, in some militaries, even so much as negligently getting blisters is a military offense.

Most of us are not soldiers, but there’s a lesson to be learned here:

Your feet are the foundation for much of the rest of your health and effectiveness.

KISS for feet

No, not like that.

Rather: “Keep It Simple, Stupid”

Dr. Starrett is not only a big fan of not overcomplicating things, but also, he tells us how overcomplicating things can actively cause problems. When it comes to footwear, for example, he advises:

❝When you wear shoes, wear the flat kind. If you’re walking the red carpet on Oscar night, fine, go ahead and wear a shoe with a heel. Once in a while is okay.

But most of the time, you should wear shoes that are flat and won’t throw your biological movement hardware into disarray.

When you have to wear shoes, whether it’s running shoes, work shoes, or combat boots, buy the flat kind, also known as “zero drop”—meaning that the heel is not raised above the forefoot (at all).

What you want to avoid, or wean yourself away from, are shoes with the heels raised higher off the ground than the forefeet.❞

Of course, going barefoot is great for this, but may not be an option for all of us when out and about. And in the home, going barefoot (or shod in just socks) will only confer health benefits if we’re actually on our feet! So… How much time do you spend on your feet at home?

Allow your feet to move like feet

By evolution, the human body is built for movement—especially walking and running. That came with moving away from hanging around in trees for fruit, to hunting and gathering between different areas of the savannah. Today, our hunting and gathering may be done at the local grocery store, but we still need to keep our mobility, especially when it comes to our feet.

Now comes the flat footwear you don’t want: flip-flops and similar

If we wear flip-flops, or other slippers or shoes that hold onto our feet only at the front, we’re no longer walking like we’re supposed to. Instead of being the elegant product of so much evolution, we’re now walking like those AT-AT walkers in Star Wars, you know, the ones that fell over so easily?

Our feet need to be able to tilt naturally while walking/running, without our footwear coming off.

Golden rule for this: if you can’t run in them, you shouldn’t be walking in them

Exception: if for example you need something on your feet for a minute or two in the shower at the gym/pool, flip-flops are fine. But anything more than that, and you want something better.

Watch your step

There’s a lot here that’s beyond the scope of what we can include in this short newsletter, but:

If we stand or walk or run incorrectly, we’re doing gradual continual damage to our feet and ankles (potentially also our knees and hips, which problems in turn have a knock-on effect for our spine, and you get the idea—this is Bad™)

Some general pointers for keeping things in good order include:

- Your weight should be mostly on the balls of your feet, not your heels

- Your feet should be pretty much parallel, not turned out or in

- When standing, your center of gravity should be balanced between heel and forefoot

Quick tip for accomplishing this last one: Stand comfortably, your feet parallel, shoulder-width apart. Now, go up on your tip-toes. When you’ve done so, note where your spine is, and keep it there (apart from in its up-down axis) when you slowly go back to having your feet flat on the ground, so it’s as though your spine is sliding down a pole that’s fixed in place.

If you do this right, your center of gravity will now be perfectly aligned with where it’s supposed to be. It might feel a bit weird at first, but you’ll get used to it, and can always reset it whenever you want/need, by repeating the exercise.

If you’d like to know more from Dr. Starrett, you can check out his website here 🙂

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The #1 Foot Health Secret Everyone Over 50 Should Know

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our favorite over-50s specialist physio Will Harlow is here to keep us on our toes:

Mobility requires mobilization

As we age, our toes are inclined to become stiffer. Stiff toes lead to balance issues and increased risk of falling.

A study cited in the video showed that two weeks of toe mobilization improved foot-ground contact by 30% in older adults, enhancing balance and reducing falls.

Here’s the routine:

- Toe flexion:

- Apply moisturizer or oil to your hands.

- Pull your toes downwards, then let them return their normal position.

- Repeat for one minute per foot.

- Toe extension:

- Rub hands from the heel under the toes.

- Push your toes upwards, then let them return to their normal position.

- Repeat for one minute per foot.

- Foot rotation:

- Hold both sides of your foot and twist it in one direction, then the other.

- This helps loosen foot joints and improve flexibility.

- Perform for one minute in each direction per foot.

For more on each of these plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Steps For Keeping Your Feet A Healthy Foundation

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

- Toe flexion:

-

What pathogen might spark the next pandemic? How scientists are preparing for ‘disease X’

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Before the COVID pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) had made a list of priority infectious diseases. These were felt to pose a threat to international public health, but where research was still needed to improve their surveillance and diagnosis. In 2018, “disease X” was included, which signified that a pathogen previously not on our radar could cause a pandemic.

While it’s one thing to acknowledge the limits to our knowledge of the microbial soup we live in, more recent attention has focused on how we might systematically approach future pandemic risks.

Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously talked about “known knowns” (things we know we know), “known unknowns” (things we know we don’t know), and “unknown unknowns” (the things we don’t know we don’t know).

Although this may have been controversial in its original context of weapons of mass destruction, it provides a way to think about how we might approach future pandemic threats.

Anna Shvets/Pexels Influenza: a ‘known known’

Influenza is largely a known entity; we essentially have a minor pandemic every winter with small changes in the virus each year. But more major changes can also occur, resulting in spread through populations with little pre-existing immunity. We saw this most recently in 2009 with the swine flu pandemic.

However, there’s a lot we don’t understand about what drives influenza mutations, how these interact with population-level immunity, and how best to make predictions about transmission, severity and impact each year.

The current H5N1 subtype of avian influenza (“bird flu”) has spread widely around the world. It has led to the deaths of many millions of birds and spread to several mammalian species including cows in the United States and marine mammals in South America.

Human cases have been reported in people who have had close contact with infected animals, but fortunately there’s currently no sustained spread between people.

While detecting influenza in animals is a huge task in a large country such as Australia, there are systems in place to detect and respond to bird flu in wildlife and production animals.

Scientists are continually monitoring a range of pathogens with pandemic potential. Edward Jenner/Pexels It’s inevitable there will be more influenza pandemics in the future. But it isn’t always the one we are worried about.

Attention had been focused on avian influenza since 1997, when an outbreak in birds in Hong Kong caused severe disease in humans. But the subsequent pandemic in 2009 originated in pigs in central Mexico.

Coronaviruses: an ‘unknown known’

Although Rumsfeld didn’t talk about “unknown knowns”, coronaviruses would be appropriate for this category. We knew more about coronaviruses than most people might have thought before the COVID pandemic.

We’d had experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) causing large outbreaks. Both are caused by viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID. While these might have faded from public consciousness before COVID, coronaviruses were listed in the 2015 WHO list of diseases with pandemic potential.

Previous research into the earlier coronaviruses proved vital in allowing COVID vaccines to be developed rapidly. For example, the Oxford group’s initial work on a MERS vaccine was key to the development of AstraZeneca’s COVID vaccine.

Similarly, previous research into the structure of the spike protein – a protein on the surface of coronaviruses that allows it to attach to our cells – was helpful in developing mRNA vaccines for COVID.

It would seem likely there will be further coronavirus pandemics in the future. And even if they don’t occur at the scale of COVID, the impacts can be significant. For example, when MERS spread to South Korea in 2015, it only caused 186 cases over two months, but the cost of controlling it was estimated at US$8 billion (A$11.6 billion).

COVID could be regarded as an ‘unknown known’. Markus Spiske/Pexels The 25 viral families: an approach to ‘known unknowns’

Attention has now turned to the known unknowns. There are about 120 viruses from 25 families that are known to cause human disease. Members of each viral family share common properties and our immune systems respond to them in similar ways.

An example is the flavivirus family, of which the best-known members are yellow fever virus and dengue fever virus. This family also includes several other important viruses, such as Zika virus (which can cause birth defects when pregnant women are infected) and West Nile virus (which causes encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain).

The WHO’s blueprint for epidemics aims to consider threats from different classes of viruses and bacteria. It looks at individual pathogens as examples from each category to expand our understanding systematically.

The US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has taken this a step further, preparing vaccines and therapies for a list of prototype pathogens from key virus families. The goal is to be able to adapt this knowledge to new vaccines and treatments if a pandemic were to arise from a closely related virus.

Pathogen X, the ‘unknown unknown’

There are also the unknown unknowns, or “disease X” – an unknown pathogen with the potential to trigger a severe global epidemic. To prepare for this, we need to adopt new forms of surveillance specifically looking at where new pathogens could emerge.

In recent years, there’s been an increasing recognition that we need to take a broader view of health beyond only thinking about human health, but also animals and the environment. This concept is known as “One Health” and considers issues such as climate change, intensive agricultural practices, trade in exotic animals, increased human encroachment into wildlife habitats, changing international travel, and urbanisation.

This has implications not only for where to look for new infectious diseases, but also how we can reduce the risk of “spillover” from animals to humans. This might include targeted testing of animals and people who work closely with animals. Currently, testing is mainly directed towards known viruses, but new technologies can look for as yet unknown viruses in patients with symptoms consistent with new infections.

We live in a vast world of potential microbiological threats. While influenza and coronaviruses have a track record of causing past pandemics, a longer list of new pathogens could still cause outbreaks with significant consequences.

Continued surveillance for new pathogens, improving our understanding of important virus families, and developing policies to reduce the risk of spillover will all be important for reducing the risk of future pandemics.

This article is part of a series on the next pandemic.

Allen Cheng, Professor of Infectious Diseases, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: