Avocado vs Olives – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing avocado to olives, we picked the avocado.

Why?

Both are certainly great! And when it comes to their respective oils, olive oil wins out as it retains many micronutrients that avocado oil loses. But, in their whole form, avocado beats olive:

In terms of macros, avocado has more protein, carbs, fiber, and (healthy) fats. Simply, it’s more nationally-dense than the already nutritionally-dense food that is olives.

When it comes to vitamins, olives are great but avocados really shine; avocado has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7 B9, C, E, K, and choline, while olives boast only more vitamin A.

In the category of minerals, things are closer to even; avocado has more magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc, while olives have a lot more calcium, copper, iron, and selenium. Still, a marginal victory for avocado here.

In short, this is another case of one very healthy food looking bad by standing next to an even better one, so by all means enjoy both—if you’re going to pick one though, avocado is the more nutritionally dense.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Avocado Oil vs Olive Oil – Which is Healthier? ← when made into oils, olive oil wins, but avocado oil is still a good option too

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why Many Nonprofit (Wink, Wink) Hospitals Are Rolling in Money

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One owns a for-profit insurer, a venture capital company, and for-profit hospitals in Italy and Kazakhstan; it has just acquired its fourth for-profit hospital in Ireland. Another owns one of the largest for-profit hospitals in London, is partnering to build a massive training facility for a professional basketball team, and has launched and financed 80 for-profit start-ups. Another partners with a wellness spa where rooms cost $4,000 a night and co-invests with “leading private equity firms.”

Do these sound like charities?

These diversified businesses are, in fact, some of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital systems. And they have somehow managed to keep myriad for-profit enterprises under their nonprofit umbrella — a status that means they pay little or no taxes, float bonds at preferred rates, and gain numerous other financial advantages.

Through legal maneuvering, regulatory neglect, and a large dollop of lobbying, they have remained tax-exempt charities, classified as 501(c)(3)s.

“Hospitals are some of the biggest businesses in the U.S. — nonprofit in name only,” said Martin Gaynor, an economics and public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “They realized they could own for-profit businesses and keep their not-for-profit status. So the parking lot is for-profit; the laundry service is for-profit; they open up for-profit entities in other countries that are expressly for making money. Great work if you can get it.”

Many universities’ most robust income streams come from their technically nonprofit hospitals. At Stanford University, 62% of operating revenue in fiscal 2023 was from health services; at the University of Chicago, patient services brought in 49% of operating revenue in fiscal 2022.

To be sure, many hospitals’ major source of income is still likely to be pricey patient care. Because they are nonprofit and therefore, by definition, can’t show that thing called “profit,” excess earnings are called “operating surpluses.” Meanwhile, some nonprofit hospitals, particularly in rural areas and inner cities, struggle to stay afloat because they depend heavily on lower payments from Medicaid and Medicare and have no alternative income streams.

But investments are making “a bigger and bigger difference” in the bottom line of many big systems, said Ge Bai, a professor of health care accounting at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. Investment income helped Cleveland Clinic overcome the deficit incurred during the pandemic.

When many U.S. hospitals were founded over the past two centuries, mostly by religious groups, they were accorded nonprofit status for doling out free care during an era in which fewer people had insurance and bills were modest. The institutions operated on razor-thin margins. But as more Americans gained insurance and medical treatments became more effective — and more expensive — there was money to be made.

Not-for-profit hospitals merged with one another, pursuing economies of scale, like joint purchasing of linens and surgical supplies. Then, in this century, they also began acquiring parts of the health care systems that had long been for-profit, such as doctors’ groups, as well as imaging and surgery centers. That raised some legal eyebrows — how could a nonprofit simply acquire a for-profit? — but regulators and the IRS let it ride.

And in recent years, partnerships with, and ownership of, profit-making ventures have strayed further and further afield from the purported charitable health care mission in their community.

“When I first encountered it, I was dumbfounded — I said, ‘This not charitable,’” said Michael West, an attorney and senior vice president of the New York Council of Nonprofits. “I’ve long questioned why these institutions get away with it. I just don’t see how it’s compliant with the IRS tax code.” West also pointed out that they don’t act like charities: “I mean, everyone knows someone with an outstanding $15,000 bill they can’t pay.”

Hospitals get their tax breaks for providing “charity care and community benefit.” But how much charity care is enough and, more important, what sort of activities count as “community benefit” and how to value them? IRS guidance released this year remains fuzzy on the issue.

Academics who study the subject have consistently found the value of many hospitals’ good work pales in comparison with the value of their tax breaks. Studies have shown that generally nonprofit and for-profit hospitals spend about the same portion of their expenses on the charity care component.

Here are some things listed as “community benefit” on hospital systems’ 990 tax forms: creating jobs; building energy-efficient facilities; hiring minority- or women-owned contractors; upgrading parks with lighting and comfortable seating; creating healing gardens and spas for patients.

All good works, to be sure, but health care?

What’s more, to justify engaging in for-profit business while maintaining their not-for-profit status, hospitals must connect the business revenue to that mission. Otherwise, they pay an unrelated business income tax.

“Their CEOs — many from the corporate world — spout drivel and turn somersaults to make the case,” said Lawton Burns, a management professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They do a lot of profitable stuff — they’re very clever and entrepreneurial.”

The truth is that a number of not-for-profit hospitals have become wealthy diversified business organizations. The most visible manifestation of that is outsize executive compensation at many of the country’s big health systems. Seven of the 10 most highly paid nonprofit CEOs in the United States run hospitals and are paid millions, sometimes tens of millions, of dollars annually. The CEOs of the Gates and Ford foundations make far less, just a bit over $1 million.

When challenged about the generous pay packages — as they often are — hospitals respond that running a hospital is a complicated business, that pharmaceutical and insurance execs make much more. Also, board compensation committees determine the payout, considering salaries at comparable institutions as well as the hospital’s financial performance.

One obvious reason for the regulatory tolerance is that hospital systems are major employers — the largest in many states (including Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Arizona, and Delaware). They are big-time lobbying forces and major donors in Washington and in state capitals.

But some patients have had enough: In a suit brought by a local school board, a judge last year declared that four Pennsylvania hospitals in the Tower Health system had to pay property taxes because its executive pay was “eye popping” and it demonstrated “profit motives through actions such as charging management fees from its hospitals.”

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report chided the IRS for its lack of vigilance in reviewing nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit and recommended ways to “improve IRS oversight.” A follow-up GAO report to Congress in 2023 said, “IRS officials told us that the agency had not revoked a hospital’s tax-exempt status for failing to provide sufficient community benefits in the previous 10 years” and recommended that Congress lay out more specific standards. The IRS declined to comment for this column.

Attorneys general, who regulate charity at the state level, could also get involved. But, in practice, “there is zero accountability,” West said. “Most nonprofits live in fear of the AG. Not hospitals.”

Today’s big hospital systems do miraculous, lifesaving stuff. But they are not channeling Mother Teresa. Maybe it’s time to end the community benefit charade for those that exploit it, and have these big businesses pay at least some tax. Communities could then use those dollars in ways that directly benefit residents’ health.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

-

The Diabetes Drugs That Can Cut Asthma Attacks By 70%

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Asthma, obesity, and type 2 diabetes are closely linked, with the latter two greatly increasing asthma attack risk.

While bronchodilators / corticosteroids can have immediate adverse effects due to sympathetic nervous system activation, and lasting adverse effects due to the damage it does to metabolic health, diabetes drugs, on the other hand, can improve things with (for most people) fewer unwanted side effects.

Great! Which drugs?

Metformin, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs).

Specifically, researchers have found:

- Metformin is associated with a 30% reduction in asthma attacks

- GLP-1RAs are associated with a 40% reduction in asthma attacks

…and yes, they stack, making for a 70% reduction in the case of people taking both. Furthermore, the results are independent of weight, glycemic control, or asthma phenotype.

In terms of what was counted, the primary outcome was asthma attacks at 12-month follow-up, defined by oral corticosteroid use, emergency visits, hospitalizations, or death.

The effect of metformin on asthma attacks was not affected by BMI, HbA1c levels, eosinophil count, asthma severity, or sex.

Of the various extra antidiabetic drugs trialled in this study, only GLP-1 receptor agonists showed a further and sustained reduction in asthma attacks.

Here’s the study itself, hot off the press, published on Monday:

JAMA Int. Med. | Antidiabetic Medication and Asthma Attacks

“But what if I’m not diabetic?”

Good news:

More than half of all US adults are eligible for semaglutide therapy ← this is because they’ve expanded the things that semaglutide (the widely-used GLP-1 receptor agonist drug) can be prescribed for, now going beyond just diabetes and/or weight loss 😎

And metformin, of course, is more readily available than semaglutide, so by all means speak with your doctor/pharmacist about that, if it’s of interest to you.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Top 10 Foods That Promote Lymphatic Drainage and Lymph Flow

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Melissa Gallagher, a naturopath by profession, recommends the following 10 foods that she says promote lymphatic drainage and lymph flow, as well as the below-mentioned additional properties:

Ginger

Ginger is a natural anti-inflammatory, which we wrote about here:

Ginger Does A Lot More Than You Think

Turmeric

Turmeric is another natural anti-inflammatory, which we wrote about here:

Why Curcumin (Turmeric) Is Worth Its Weight In Gold

Garlic

Garlic is—you guessed it—another natural anti-inflammatory which we wrote about here:

The Many Health Benefits Of Garlic

Pineapple

Pineapple contains a collection of enzymes collectively called bromelain—which is a unique kind of anti-inflammatory, and which we have written about here:

Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

Citrus

Citrus fruits like oranges, lemons, and grapefruits are rich in vitamin C, which can help support the immune system in general.

Cranberry

Cranberries contain antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, which we wrote about here:

Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

The video also explains how cranberry bioactives inhibit adipogenesis and reduces fat congestion in your lymphatic system.

Dandelion Tea

Dandelion is a natural diuretic and anti-inflammatory herb, which we’ve not written about yet!

Nettle Tea

Nettle is a natural diuretic and anti-inflammatory herb, which we’ve also not written about yet!

Healthy Fats

Healthy fats like avocado, nuts, and olive oil can help reduce inflammation and support the immune system.

Fermented Foods

Fermented foods, such as kimchi and sauerkraut, contain probiotics that can improve gut health, which in turn boosts the immune system. You can read all about it here:

Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

Want the full explanation? Here’s the video:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

My dance school is closed for the summer, how can I keep up my fitness?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Once the end-of-year dance concert and term wrap up for the year it is important to take a break. Both physical and mental rest are important and taking a few weeks off can help your body repair and have a mental break from dance.

If your mind and body are in need of an extended break (such as more than a few weeks), then it’s more than OK to take longer off, especially if you are training at a competitive or pre-professional level.

There is benefit in enjoying other aspects of your life outside of dance such as spending time with family, friends and enjoying hobbies.

Tatyana Vyc/Shutterstock A safe, fulfilling dancing life

Creating meaning and value in life outside of dance and expanding sense of self can make it easier to lean into other aspects when experiencing change or difficult times during dance training such as being injured.

Taking an extended break from dance training will, however, mean losing some fitness and physical capacity. When you return to dance your body will take time to return to full capacity again.

Approaches such as being “whipped back into shape” can promote sudden spikes in training load (hours and intensity of training) which can increase the risk of injury. It is advised to gradually and progressively increase training load over time to allow the body to adapt and return to full capacity safely.

A four-to-six week period of gradually progressing training load and introducing jumping has been suggested in dance settings.

For dancers wanting to maintain fitness over the summer holidays, a great place to start is focusing on building a physical foundation.

Exercise like running can help build a physical foundation. Jacek Chabraszewski/Shutterstock Building a physical foundation means focusing on targeted areas of fitness such as full body strength, cardiovascular fitness or stamina (such as skipping, cycling walking, running, swimming), flexibility, and some dance-specific conditioning (for example, calf rises for ballet).

A good physical foundation will mean an improved capacity and fitness level so your body is ready to take on more challenging dance movements and routines once you return to the studio.

Building full body strength at home or at the park

A great place to start is by choosing movements that require your muscles to work to support your own body weight.

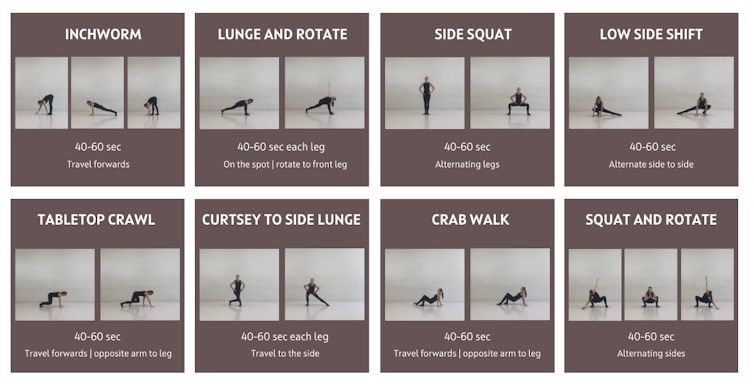

Fundamental movements such as crawling (moving on the floor on hands and feet) and locomotion (travelling movements such as lunging, hopping, sliding) are great for developing body control, arm and leg stability and coordinated movement patterns.

Below is a sequence that can be used as a warm up and even as a workout itself. The ten minute sequence is based on gross motor and fundamental movement patterns. It includes exercises that work through a range of joint movements and in multiple planes (forwards, sideways, rotating).

This fundamental movement sequence can be used as a warm-up or a workout. Joanna Nicholas, CC BY Once feeling comfortable with the above fundamental movements, it is time to introduce body weight resistance exercises.

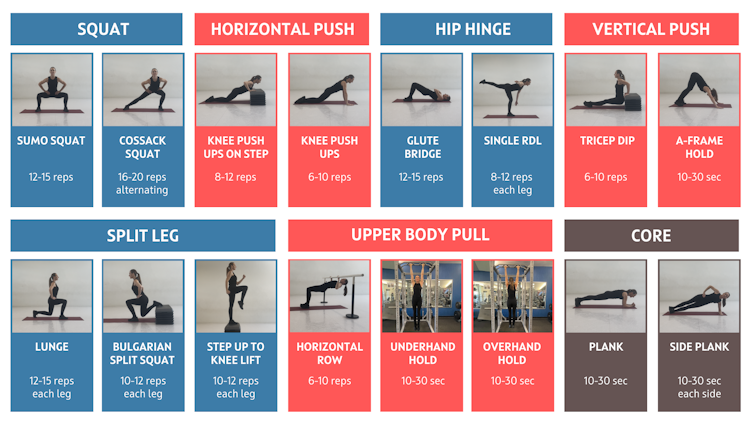

Body weight resistance exercises can be beneficial for developing a strong foundation for dance movements such as jumping, landing, floorwork, partnering and aerial work.

Exercises from the above sequence can be used to form a safe and effective neuromuscular warm up.

Aim to include one exercise from each of the below movement categories (squat, horizontal push etc) to build your own workout.

Aim to complete two to three sets (or rounds) of each exercise with about one minute rest between sets. An alternative is to complete one set of each exercise with minimal rest between, then complete a second or third time.

If training with friends, you could set a timer and do each exercise for up to 50 seconds (instead of counting reps) and take ten seconds to transition to the next exercise.

Depending on your level of strength you may need to do fewer repetitions and build up sets and repetitions overtime. After you have completed the body weight exercises complete a cool down including stretches for the upper and lower body muscles. Be sure to use a sturdy bar (such as an outdoor fitness station) for horizontal row and overhead hold.

Exercises may need to be modified depending on fitness level and physical limitations such as injury.

You can build your own full body strength workout using these movements. Joanna Nicholas, CC BY How often should I train?

A common misconception in dance is that “more is better”. This belief can lead to dancers training long hours on most or all days of the week which can lead to overtraining, plateauing and increased risk of injury.

Our bodies require sufficient time between training sessions to adapt and get stronger and fitter. The time between sessions is when our muscles and tissues repair and training gains are made.

By incorporating adequate recovery (including sleep and downtime) and including rest days throughout the week, our bodies can gain the most benefits from training.

Rest days are important, too. Manop Boonpeng/Shutterstock Muscles can take up to 48–72 hours to recover from most types of strength-based exercises (the more intense the longer they’ll need to recover).

Aerobic activity at low intensity, such as a brisk walk, can be done most days (24-hour recovery) while high stress anaerobic exercise such as high intensity intervals or sprints can take three days or more to recover from.

Aim to spread training sessions out over the week and allow time to recover between sessions.

Below is an example weekly schedule based on incorporating adequate recovery between sessions, and incorporating polarised training where some days are harder and others are easier.

Seek guidance from your healthcare provider and/or an exercise professional prior to undertaking a new exercise program.

Joanna Nicholas, Lecturer in Dance and Performance Science, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Topping Up Testosterone?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Testosterone Drop

Testosterone levels decline amongst men over a certain age. Exactly when depends on the individual and also how we measure it, but the age of 45 is a commonly-given waypoint for the start of this decline.

(the actual start is usually more like 20, but it’s a very small decline then, and speeds up a couple of decades later)

This has been called “the male menopause”, or “the andropause”.

Both terms are a little misleading, but for lack of a better term, “andropause” is perhaps not terrible.

Why “the male menopause” is misleading:

To call it “the male menopause” suggests that this is when men’s menstruation stops. Which for cis men at the very least, is simply not a thing they ever had in the first place, to stop (and for trans men it’s complicated, depending on age, hormones, surgeries, etc).

Why “the andropause” is misleading:

It’s not a pause, and unlike the menopause, it’s not even a stop. It’s just a decline. It’s more of an andro-pitter-patter-puttering-petering-out.

Is there a better clinical term?

Objectively, there is “late-onset hypogonadism” but that is unlikely to be taken up for cultural reasons—people stigmatize what they see as a loss of virility.

Terms aside, what are the symptoms?

❝Andropause or late-onset hypogonadism is a common disorder which increases in prevalence with advancing age. Diagnosis of late-onset of hypogonadism is based on presence of symptoms suggestive of testosterone deficiency – prominent among them are sexual symptoms like…❞

…and there we’d like to continue the quotation, but if we list the symptoms here, it won’t get past a lot of filters because of the words used. So instead, please feel free to click through:

Source: Andropause: Current concepts

Can it be safely ignored?

If you don’t mind the sexual symptoms, then mostly, yes!

However, there are a few symptoms we can mention here that are not so subjective in their potential for harm:

- Depression

- Loss of muscle mass

- Increased body fat

Depression kills, so this does need to be taken seriously. See also:

The Mental Health First-Aid That You’ll Hopefully Never Need

(the above is a guide to managing depression, in yourself or a loved one)

Loss of muscle mass means being less robust against knocks and falls later in life

Loss of muscle mass also means weaker bones (because the body won’t make bones stronger than it thinks they need to be, so bone will follow muscle in this regard—in either direction)

See also:

- Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

- Protein vs Sarcopenia

- Fall Special (How to Proof Yourself Against Falls)

Increased body fat means increased risk of diabetes and heart disease, as a general rule of thumb, amongst other problems.

Will testosterone therapy help?

That’s something to discuss with your endocrinologist, but for most men whose testosterone levels are lower than is ideal for them, then yes, taking testosterone to bring them [back] to “normal” levels can make you happier and healthier (though it’s certainly not a cure-all).

See for example:

Testosterone Therapy Improves […] and […] in Hypogonadal Men

(Sorry, we’re not trying to be clickbaity, there are just some words we can’t use without encountering software problems)

Here’s a more comprehensive study that looked at 790 men aged 65 or older, with testosterone levels below a certain level. It looked at the things we can’t mention here, as well as physical function and general vitality:

❝The increase in testosterone levels was associated with significantly increased […] activity, as assessed by the Psychosexual Daily Questionnaire (P<0.001), as well as significantly increased […] desire and […] function.

The percentage of men who had an increase of at least 50 m in the 6-minute walking distance did not differ significantly between the two study groups in the Physical Function Trial but did differ significantly when men in all three trials were included (20.5% of men who received testosterone vs. 12.6% of men who received placebo, P=0.003).

Testosterone had no significant benefit with respect to vitality, as assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue scale, but men who received testosterone reported slightly better mood and lower severity of depressive symptoms than those who received placebo❞

Source: Effects of Testosterone Treatment in Older Men

We strongly recommend, by the way, when a topic is of interest to you to read the paper itself, because even the extract above contains some subjectivity, for example what is “slightly better”, and what is “no significant benefit”.

That “slightly better mood and lower severity of depressive symptoms”, for example, has a P value of 0.004 in their data, which is an order of magnitude more significant than the usual baseline for significance (P<0.05).

And furthermore, that “no significant benefit with respect to vitality” is only looking at either the primary outcome aggregated goal or the secondary FACIT score whose secondary outcome had a P value of 0.06, which just missed the cut-off for significance, and neglects to mention that all the other secondary outcome metrics for men involved in the vitality trial were very significant (ranging from P=0.04 to P=0.001)

Click here to see the results table for the vitality trial

Will it turn me into a musclebound angry ragey ‘roidmonster?

Were you that kind of person before your testosterone levels declined? If not, then no.

Testosterone therapy seeks only to return your testosterone levels to where they were, and this is done through careful monitoring and adjustment. It’d take a lot more than (responsible) endocrinologist-guided hormonal therapy to turn you into Marvel’s “Wolverine”.

Is testosterone therapy safe?

A question to take to your endocrinologist because everyone’s physiology is different, but a lot of studies do support its general safety for most people who are prescribed it.

As with anything, there are risks to be aware of, though. Perhaps the most critical risk is prostate cancer, and…

❝In a large meta-analysis of 18 prospective studies that included over 3500 men, there was no association between serum androgen levels and the risk of prostate cancer development

For men with untreated prostate cancer on active surveillance, TRT remains controversial. However, several studies have shown that TRT is not associated with progression of prostate cancer as evidenced by either PSA progression or gleason grade upstaging on repeat biopsy.

Men on TRT should have frequent PSA monitoring; any major change in PSA (>1 ng/mL) within the first 3-6 months may reflect the presence of a pre-existing cancer and warrants cessation of therapy❞

Those are some select extracts, but any of this may apply to you or your loved one, we recommend to read in full about this and other risks:

Risks of testosterone replacement therapy in men

See also: Prostate Health: What You Should Know

Beyond that… If you are prone to baldness, then taking testosterone will increase that tendency. If that’s a problem for you, then it’s something to know about. There are other things you can take/use for that in turn, so maybe we’ll do a feature on those one of these days!

For now, take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Fat’s Real Barriers To Health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Fat Justice In Healthcare

This is Aubrey Gordon, an author, podcaster, and fat justice activist. What does that mean?

When it comes to healthcare, we previously covered some ideas very similar to her work, such as how…

There’s a lot of discrimination in healthcare settings

In this case, it often happens that a thin person goes in with a medical problem and gets treated for that, while a fat person can go in with the same medical problem and be told “you should try losing some weight”.

Top tip if this happens to you… Ask: “what would you advise/prescribe to a thin person with my same symptoms?”

Other things may be more systemic, for example:

When a thin person goes to get their blood pressure taken, and that goes smoothly, while a fat person goes to get their blood pressure taken, and there’s not a blood pressure cuff to fit them, is the problem the size of the person or the size of the cuff? It all depends on perspective, in a world built around thin people.

That’s a trivial-seeming example, but the same principle has far-reaching (and harmful) implications in healthcare in general, e.g:

- Surgeons being untrained (and/or unwilling) to operate on fat people

- Getting a one-size-fits-all dose that was calculated using average weight, and now doesn’t work

- MRI machines are famously claustrophobia-inducing for thin people; now try not fitting in it in the first place

…and so forth. So oftentimes, obesity will be correlated with a poor healthcare outcome, where the problem is not actually the obesity itself, but rather the system having been set up with thin people in mind.

It would be like saying “Having O- blood type results in higher risks when receiving blood transfusions”, while omitting to add “…because we didn’t stock O- blood”.

Read more on this topic: Shedding Some Obesity Myths

Does she have practical advice about this?

If she could have you understand one thing, it would be:

You deserve better.

Or if you are not fat: your fat friends deserve better.

How this becomes useful is: do not accept being treated as the problem!

Demand better!

If you meekly accept that you “just need to lose weight” and that thus you are the problem, you take away any responsibility from your healthcare provider(s) to actually do their jobs and provide healthcare.

See also Gordon’s book, which we’ve not reviewed yet but probably will one of these days:

“You Just Need to Lose Weight”: And 19 Other Myths About Fat People – by Aubrey Gordon

Are you saying fat people don’t need to lose weight?

That’s a little like asking “would you say office workers don’t need to exercise more?”; there are implicit assumptions built into the question that are going unaddressed.

Rather: some people might benefit healthwise from losing weight, some might not.

In fact, over the age of 65, being what is nominally considered “overweight” reduces all-cause mortality risk.

For details of that and more, see: When BMI Doesn’t Measure Up

But what if I do want/need to lose weight?

Gordon’s not interested in helping with that, but we at 10almonds are, so…

Check out: Lose Weight, But Healthily

Where can I find more from Aubrey Gordon?

You might enjoy her blog:

Aubrey Gordon | Your Fat Friend

Or her other book, which we reviewed previously:

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat – by Aubrey Gordon

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: