Knee Cracking & Popping: Should You Be Worried?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Tom Walters (Doctor of Physical Therapy) explains about what’s going on behind our musical knees, and whether or not this synovial symphony is cause for concern.

When to worry (and when not to)

If the clicking/cracking/popping/etc does not come with pain, then it is probably being caused by the harmless movement of fluid within the joints, in this case specifically the patellofemoral joint, just behind the kneecap.

As Dr. Walters says:

❝It is extremely important that people understand that noises from the knee are usually not associated with pathology and may actually be a sign of a healthy, well-lubricated joint. let’s be careful not to make people feel bad about their knee noise as it can negatively influence how they view their body!❞

On the other hand, there is also such a thing as patellofemoral joint pain syndrome (PFPS), which is very common, and involves pain behind the kneecap, especially upon over-stressing the knee(s).

In such cases, it is good to get that checked out by a doctor/physiotherapist.

Dr. Walters advises us to gradually build up strength, and not try for too much too quickly. He also advises us to take care to strengthen our glutes in particular, so our knees have adequate support. Gentle stretching of the quadriceps and soft tissue mobilization with a foam roller, are also recommended, to reduce tension on the kneecap.

For more on these things and especially about the exercises, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

How To Really Take Care Of Your Joints

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Not To Get Sick: A Cookbook – by Dr. Benjamin Bikman and Diana Keuilian

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Dr. Bikman’s excellent “Why We Get Sick”, and if you haven’t read that yet, we recommend doing so.

Nevertheless, you don’t need to have read it to benefit from this one, which is about cooking with those learnings (from the other book) in mind.

Before getting to the recipes, we get a section recapping what we learned previously, as well as adding some more general lifestyle advices beyond the kitchen. The science is also expanded a bit, to include such things as the two-way relationship between insulin and aging, as well as the interplay with other metrics of health, including blood lipids, for example.

The authors then provide a plan, in the three stages: reverse (insulin resistance), prevent (insulin resistance), maintain (insulin sensitivity).

The recipes themselves, of which there are 70, are of course tailored to do the above three things; they’re also quite diverse, albeit if you are vegetarian or vegan, you should know in advance that most of these recipes are not.

Bottom line: if the above doesn’t apply to you, and you would like to improve your insulin sensitivity, this book can indeed help.

Share This Post

-

If Your Adult Kid Calls In Crisis…

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Parent(s) To The Rescue?

We’ve written before about the very common (yes, really, it is common) phenomenon of estrangement between parents and adult children:

Family Estrangement & How To Fix It

We’ve also written about the juggling act that can be…

Managing Sibling Relationships In Adult Life

…which includes dealing with such situations as supporting each other through difficult times, while still maintaining healthy boundaries.

But what about when one’s [adult] child is in crisis?

When a parent’s job never ends

Hopefully, we have not been estranged (or worse, bereaved) by our children.

In which case, when crisis hits, we are likely to be amongst the first to whom our children will reach out for support. Naturally, we will want to help. But how can we do that, and where (if applicable) to draw the line?

No “helicopter parenting”

If you’ve not heard the term “helicopter parenting”, it refers to the sort of parents who hover around, waiting to swoop in at a moment’s notice.

This is most often applied to parents of kids of university age and downwards, but it’s worth keeping it in mind at any age.

After all, we do want our kids to be able to solve their own problems if possible!

So, if you’ve ever advised your kid to “take a deep breath and count to 10” (or even if you haven’t), then, consider doing that too, and then…

Listen first!

If your first reaction isn’t to join them in panic, it might be to groan and “oh not again”. But for now, quietly shelve that, and listen to whatever it is.

See also: Active Listening (Without Sounding Like A Furby)

And certainly, do your best to maintain your own calm while listening. Your kid is in all likelihood looking to you to be the rock in the storm, so let’s be that.

Empower them, if you can

Maybe they just needed to vent. If so, the above will probably cover it.

More likely, they need help.

Perhaps they need guidance, from your greater life experience. Sometimes things that can seem like overwhelming challenges to one person, are a thing we dealt with 20 or more years ago (it probably felt overwhelming to us at the time, too, but here we are, the other side of it).

Tip: ask “are you looking for my guidance/advice/etc?” before offering it. Doing so will make it much more likely to be accepted rather than rejected as unsolicited advice.

Chances are, they will take the life-ring offered.

It could be that that’s not what they had in mind, and they’re looking for material support. If so…

When it’s about money or similar

Tip: it’s worth thinking about this sort of thing in advance (now is great, if you have adult kids), and ask yourself nowwhat you’d be prepared to give in that regard, e.g:

- if they need money, how much (if any) are you willing and able to provide?

- if they want/need to come stay with you, how prepared are you for that (including: if they want/need to actually move back in with you for a while, which is increasingly common these days)?

Having these answers in your head ready will make the conversation a lot less difficult in the moment, and will avoid you giving a knee-jerk response you might regret (in either direction).

Have a counteroffer up your sleeve if necessary

Maybe:

- you can’t solve their life problem for them, but you can help them find a therapist (if applicable, for example)

- you can’t solve their money problem for them, but you can help them find a free debt advice service (if applicable, for example)

- you can’t solve their residence problem for them, but you can help them find a service that can help with that (if applicable, for example)

You don’t need to brainstorm now for every option; you’re a parent, not Batman. But it’s a lot easier to think through such hypothetical thought-experiments now, than it will be with your fraught kid on the phone later.

Magic words to remember: “Let’s find a way through this for you”

Don’t forget to look after yourself

Many of us, as parents, will tend to not think twice before sacrificing something for our kid(s). That’s generally laudable, but we must avoid accidentally becoming “the giving tree” who has nothing left for ourself, and that includes our mental energy and our personal peace.

That doesn’t mean that when our kid comes in crisis we say “Shh, stop disturbing my personal peace”, but it does mean that we remember to keep at least some boundaries (also figure out now what they are, too!), and to take care of ourselves too.

The following article was written with a slightly different scenario in mind, but the advice remains just as valid here:

How To Avoid Carer Burnout (Without Dropping Care)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

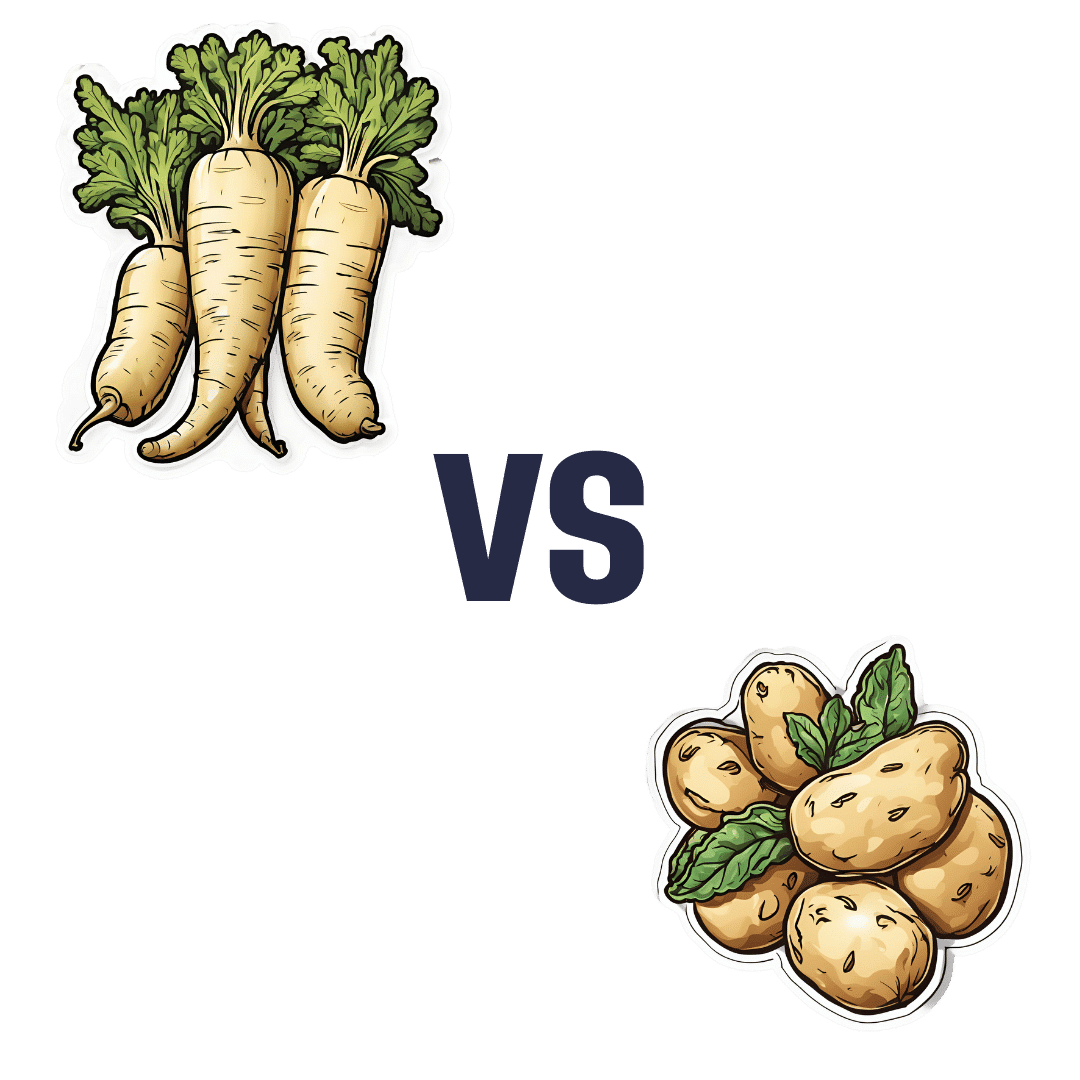

Parsnips vs Potatoes – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing parsnips to potatoes, we picked the parsnips.

Why?

To be more specific, we’re looking at russet potatoes, and in both cases we’re looking at cooked without fat or salt, skin on. In other words, the basic nutritional values of these plants in edible form, without adding anything. With this in mind, once we get to the root of things, there’s a clear winner:

Looking at the macros first, potatoes have more carbs while parsnips have more fiber. Potatoes do have more protein too, but given the small numbers involved when it comes to protein we don’t think this is enough of a plus to outweigh the extra fiber in the parsnips.

In the category of vitamins, again a champion emerges: parsnips have more of vitamins B1, B2, B5, B9, C, E, and K, while potatoes have more of vitamins B3, B6, and choline. So, a 7:3 win for parsnips.

When it comes to minerals, parsnips have more calcium copper, manganese, selenium, and zinc, while potatoes have more iron and potassium. Potatoes do also have more sodium, but for most people most of the time, this is not a plus, healthwise. Disregarding the sodium, this category sees a 5:2 win for parsnips.

In short: as with most starchy vegetables, enjoy both in moderation if you feel so inclined, but if you’re picking one, then parsnips are the nutritionally best choice here.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

- Should You Go Light Or Heavy On Carbs?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Purpose – by Gina Bianchini

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

To address the elephant in the room, this is not a rehash of Rick Warren’s best-selling “The Purpose-Driven Life”. Instead, this book is (in this reviewer’s opinion) a lot better. It’s a lot more comprehensive, and it doesn’t assume that what’s most important to the author will be what’s most important to you.

What’s it about, then? It’s about giving your passion (whatever it may be) the tools to have an enduring impact on the world. It recommends doing this by leveraging a technology that would once have been considered magic: social media.

Far from “grow your brand” business books, this one looks at what really matters the most to you. Nobody will look back on your life and say “what a profitable second quarter that was in such-a-year”. But if you do your thing well, people will look back and say:

- “he was a pillar of the community”

- “she raised that community around her”

- “they did so much for us”

- “finding my place in that community changed my life”

- …and so forth. Isn’t that something worth doing?

Bianchini takes the position of both “idealistic dreamer” and “realistic worker”.

Further, she blends the two beautifully, to give practical step-by-step instructions on how to give life to the community that you build.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Loving Someone Who Has Dementia – by Dr. Pauline Boss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We previously reviewed Dr. Boss’s excellent book “Loss, Trauma, and Resilience: Therapeutic Work With Ambiguous Loss”, which partially overlaps in ideas with this one. In that case, it was about grief when a loved one is “gone, but are they really?”, which can include missing persons, people killed in ways that weren’t 100% confirmed (e.g. no body to bury), and in contrast, people who are present in body but not entirely present mentally: perhaps in a coma, for example. It also includes people are for other reasons not entirely present in the way they used to be, which includes dementia. And that latter case is what this book focuses on.

In the case of dementia, we cannot, of course, simply focus on ourselves. Well, not if we care about the person with dementia, anyway. Much like with the other kinds of ambiguous loss, we cannot fully come to terms with things while on the cusp of presence and absence, and we cannot, as such, “give up” on our loved one.

What then, of hope? The author makes the case for—in absence of any kind of closure—making our peace with the situation as it is, making our peace with the uncertainty of things. And that means not only “at any moment could come a more clearly complete loss”, but also on the flipside at least a faint candle of hope, that we should not grasp with both hands (that is not how to treat a candle, literally or metaphorically), but rather, hold gently, and enjoy its gentle light.

Dr. Boss also covers more practical considerations; family rituals, celebrations, gatherings, and the idea of “the good-enough relationship”. Particularly helpfully, she gives her “seven guidelines for the journey”, which even if one decides against adopting them all, are definitely all good things to at least have considered.

The style is much more tailored to the lay reader than the other book of hers that we reviewed, which was intended more for clinicians, but useful also for those of us who have been hit by such kinds of grief. In this case, however, her intention is first and foremost for the family of a person who has dementia—there are still footnotes throughout though, for those who still want to read scientific papers that support the various ideas discussed in the book.

Bottom line: if a loved one has dementia or that seems a likely possibility for you, this book can help a lot!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Drug companies pay doctors over A$11 million a year for travel and education. Here’s which specialties received the most

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Drug companies are paying Australian doctors millions of dollars a year to fly to overseas conferences and meetings, give talks to other doctors, and to serve on advisory boards, our research shows.

Our team analysed reports from major drug companies, in the first comprehensive analysis of its kind. We found drug companies paid more than A$33 million to doctors in the three years from late 2019 to late 2022 for these consultancies and expenses.

We know this underestimates how much drug companies pay doctors as it leaves out the most common gift – food and drink – which drug companies in Australia do not declare.

Due to COVID restrictions, the timescale we looked at included periods where doctors were likely to be travelling less and attending fewer in-person medical conferences. So we suspect current levels of drug company funding to be even higher, especially for travel.

Monster Ztudio/Shutterstock What we did and what we found

Since 2019, Medicines Australia, the trade association of the brand-name pharmaceutical industry, has published a centralised database of payments made to individual health professionals. This is the first comprehensive analysis of this database.

We downloaded the data and matched doctors’ names with listings with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra). We then looked at how many doctors per medical specialty received industry payments and how much companies paid to each specialty.

We found more than two-thirds of rheumatologists received industry payments. Rheumatologists often prescribe expensive new biologic drugs that suppress the immune system. These drugs are responsible for a substantial proportion of drug costs on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

The specialists who received the most funding as a group were cancer doctors (oncology/haematology specialists). They received over $6 million in payments.

This is unsurprising given recently approved, expensive new cancer drugs. Some of these drugs are wonderful treatment advances; others offer minimal improvement in survival or quality of life.

A 2023 study found doctors receiving industry payments were more likely to prescribe cancer treatments of low clinical value.

Our analysis found some doctors with many small payments of a few hundred dollars. There were also instances of large individual payments.

Why does all this matter?

Doctors usually believe drug company promotion does not affect them. But research tells a different story. Industry payments can affect both doctors’ own prescribing decisions and those of their colleagues.

A US study of meals provided to doctors – on average costing less than US$20 – found the more meals a doctor received, the more of the promoted drug they prescribed.

Pizza anyone? Even providing a cheap meal can influence prescribing. El Nariz/Shutterstock Another study found the more meals a doctor received from manufacturers of opioids (a class of strong painkillers), the more opioids they prescribed. Overprescribing played a key role in the opioid crisis in North America.

Overall, a substantial body of research shows industry funding affects prescribing, including for drugs that are not a first choice because of poor effectiveness, safety or cost-effectiveness.

Then there are doctors who act as “key opinion leaders” for companies. These include paid consultants who give talks to other doctors. An ex-industry employee who recruited doctors for such roles said:

Key opinion leaders were salespeople for us, and we would routinely measure the return on our investment, by tracking prescriptions before and after their presentations […] If that speaker didn’t make the impact the company was looking for, then you wouldn’t invite them back.

We know about payments to US doctors

The best available evidence on the effects of pharmaceutical industry funding on prescribing comes from the US government-run program called Open Payments.

Since 2013, all drug and device companies must report all payments over US$10 in value in any single year. Payment reports are linked to the promoted products, which allows researchers to compare doctors’ payments with their prescribing patterns.

Analysis of this data, which involves hundreds of thousands of doctors, has indisputably shown promotional payments affect prescribing.

Medical students need to know about this. LightField Studios/Shutterstock US research also shows that doctors who had studied at medical schools that banned students receiving payments and gifts from drug companies were less likely to prescribe newer and more expensive drugs with limited evidence of benefit over existing drugs.

In general, Australian medical faculties have weak or no restrictions on medical students seeing pharmaceutical sales representatives, receiving gifts, or attending industry-sponsored events during their clinical training. They also have no restrictions on academic staff holding consultancies with manufacturers whose products they feature in their teaching.

So a first step to prevent undue pharmaceutical industry influence on prescribing decisions is to shelter medical students from this influence by having stronger conflict-of-interest policies, such as those mentioned above.

A second is better guidance for individual doctors from professional organisations and regulators on the types of funding that is and is not acceptable. We believe no doctor actively involved in patient care should accept payments from a drug company for talks, international travel or consultancies.

Third, if Medicines Australia is serious about transparency, it should require companies to list all payments – including those for food and drink – and to link health professionals’ names to their Ahpra registration numbers. This is similar to the reporting standard pharmaceutical companies follow in the US and would allow a more complete and clearer picture of what’s happening in Australia.

Patients trust doctors to choose the best available treatments to meet their health needs, based on scientific evidence of safety and effectiveness. They don’t expect marketing to influence that choice.

Barbara Mintzes, Professor, School of Pharmacy and Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney and Malcolm Forbes, Consultant psychiatrist and PhD candidate, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: