Zuranolone: What to know about the pill for postpartum depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In the year after giving birth, about one in eight people who give birth in the U.S. experience the debilitating symptoms of postpartum depression (PPD), including lack of energy and feeling sad, anxious, hopeless, and overwhelmed.

Postpartum depression is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition that can affect a person’s bond with their baby. Although it’s frequently confused with the so-called “baby blues,” it’s not the same.

The baby blues include similar, temporary symptoms that affect up to 80 percent of people who have recently given birth and usually go away within the first few weeks. PPD usually begins within the first month after giving birth and can last for months and interfere with a person’s daily life if left untreated. Thankfully, PPD is treatable and there is help available.

On August 4, the FDA approved zuranolone, branded as Zurzuvae, the first-ever oral medication to treat PPD. Until now, besides other common antidepressants, the only medication available to treat PPD specifically was the IV injection brexanolone, which is difficult to access and expensive and can only be administered in a hospital or health care setting.

Read on to find out more about zuranolone: what it is, how it works, how much it costs, and more.

What is zuranolone?

Zurzuvae is the brand name for zuranolone, an oral medication to treat postpartum depression. Developed by Sage Therapeutics in partnership with Biogen, it’s now available in the U.S. Zurzuvae is typically prescribed as two 25 mg capsules a day for 14 days. In clinical trials, the medication showed to be fast-acting, improving PPD symptoms in just three days.

How does zuranolone work?

Zuranolone is a neuroactive steroid, a type of medication that helps the neurotransmitter GABA’s receptors, which affect how the body reacts to anxiety, stress, and fear, function better.

“Zuranolone can be thought of as a synthetic version of [the neuroactive steroid] allopregnanolone,” says Dr. Katrina Furey, a reproductive psychiatrist, clinical instructor at Yale University, and co-host of the Analyze Scripts podcast. “Women with PPD have lower levels of allopregnenolone compared to women without PPD.”

How is it different from other antidepressants?

“What differentiates zuranolone from other previously available oral antidepressants is that it has a much more rapid response and a shorter course of treatment,” says Dr. Asima Ahmad, an OB-GYN, reproductive endocrinologist, and founder of Carrot Fertility.

“It can take effect as early as on day three of treatment, versus other oral antidepressants that can take up to six to 12 weeks to take full effect.”

What are Zurzuvae’s side effects?

According to the FDA, the most common side effects of Zurzuvae include dizziness, drowsiness, diarrhea, fatigue, the common cold, and urinary tract infection. Similar to other antidepressants, the medication may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions in people 24 and younger. However, NPR noted that this type of labeling is required for all antidepressants, and researchers didn’t see any reports of suicidal thoughts in their trials.

“Drug trials also noted that the side effects for zuranolone were not as severe,” says Ahmad. “[There was] no sudden loss of consciousness as seen with brexanolone or weight gain and sexual dysfunction, which can be seen with other oral antidepressants.”

She adds: “Given the lower incidence of side effects and more rapid-acting onset, zuranolone could be a viable option for many,” including those looking for a treatment that offers faster symptom relief.

Can someone breastfeed while taking zuranolone?

It’s complicated. In clinical trials, participants were asked to stop breastfeeding (which, according to Furey, is common in early clinical trials).

A small study of people who were nursing while taking zuranolone found that 0.3 percent of the medication dose was passed on to breast milk, which, Furey says, is a pretty low amount of exposure for the baby. Ahmad says that “though some data suggests that the risk of harm to the baby may be low, there is still overall limited data.”

Overall, people should talk to their health care provider about the risks and benefits of breastfeeding while on the medication.

“A lot of factors will need to be weighed, such as overall health of the infant, age of the infant, etc., when making this decision,” Furey says.

How much does Zurzuvae cost?

Zurzuvae’s price before insurance coverage is $15,900 for the 14-day treatment. However, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health says insurance companies and Medicaid are expected to cover it because it’s the only drug of its kind.

Less than 1 percent of U.S. insurers have issued coverage guidelines so far, so it’s still unknown how much it will cost patients after insurance. Some insurers require patients to try another antidepressant first (like the more common SSRIs) before covering Zurzuvae. For uninsured and underinsured people, Sage Therapeutics said it will offer copay assistance.

The hefty price tag and potential issues with coverage may widen existing health disparities, says Ahmad. “We need to ensure that we are seeking out solutions to enable wide-scale access to all PPD treatments so that people have access to whatever treatment may work best for them.”

If you or anyone you know is considering suicide or self-harm or is anxious, depressed, upset, or needs to talk, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741. For international resources, here is a good place to begin.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Tips for Avoiding PFAs

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Hi, do you have anything helpful on avoiding PFAs?❞

PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are “forever chemicals” made specifically to avoid degradation of industrial and chemical products. Which is great for providing stain and water resistance, but not so great for our bodies or the environment.

To go into all the harms they cause would take a main feature (maybe we will, one of these days), but suffice it to say, they’re not good, and range from cancer and insulin resistance to hypertension and reduced immune response.

To answer your question in a nutshell, avoiding them completely would be almost impossible, but we can reduce our exposure a lot by avoiding single-use food/drink products that have been waterproofed, e.g. paper/bamboo straws, utensils, cups, dishes, take-out containers, etc.

Also, anything advertised as “stain-resistant” that you suspect should be quite stainable by nature, is probably good to avoid too.

For more detailed information than we have room for here today, here’s a helpful overview:

Share This Post

-

As the U.S. Struggles With a Stillbirth Crisis, Australia Offers a Model for How to Do Better

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Series: Stillbirths:When Babies Die Before Taking Their First Breath

The U.S. has not prioritized stillbirth prevention, and American parents are losing babies even as other countries make larger strides to reduce deaths late in pregnancy.

The stillbirth of her daughter in 1999 cleaved Kristina Keneally’s life into a before and an after. It later became a catalyst for transforming how an entire country approaches stillbirths.

In a world where preventing stillbirths is typically far down the list of health care priorities, Australia — where Keneally was elected as a senator — has emerged as a global leader in the effort to lower the number of babies that die before taking their first breaths. Stillbirth prevention is embedded in the nation’s health care system, supported by its doctors, midwives and nurses, and touted by its politicians.

In 2017, funding from the Australian government established a groundbreaking center for research into stillbirths. The next year, its Senate established a committee on stillbirth research and education. By 2020, the country had adopted a national stillbirth plan, which combines the efforts of health care providers and researchers, bereaved families and advocacy groups, and lawmakers and government officials, all in the name of reducing stillbirths and supporting families. As part of that plan, researchers and advocates teamed up to launch a public awareness campaign. All told, the government has invested more than $40 million.

Meanwhile, the United States, which has a far larger population, has no national stillbirth plan, no public awareness campaign and no government-funded stillbirth research center. Indeed, the U.S. has long lagged behind Australia and other wealthy countries in a crucial measure: how fast the stillbirth rate drops each year.

According to the latest UNICEF report, the U.S. was worse than 151 countries in reducing its stillbirth rate between 2000 and 2021, cutting it by just 0.9%. That figure lands the U.S. in the company of South Sudan in Africa and doing slightly better than Turkmenistan in central Asia. During that period, Australia’s reduction rate was more than double that.

Definitions of stillbirth vary by country, and though both Australia and the U.S. mark stillbirths as the death of a fetus at 20 weeks or more of pregnancy, to fairly compare countries globally, international standards call for the use of the World Health Organization definition that defines stillbirth as a loss after 28 weeks. That puts the U.S. stillbirth rate in 2021 at 2.7 per 1,000 total births, compared with 2.4 in Australia the same year.

Every year in the United States, more than 20,000 pregnancies end in a stillbirth. Each day, roughly 60 babies are stillborn. Australia experiences six stillbirths a day.

Over the past two years, ProPublica has revealed systemic failures at the federal and local levels, including not prioritizing research, awareness and data collection, conducting too few autopsies after stillbirths and doing little to combat stark racial disparities. And while efforts are starting to surface in the U.S. — including two stillbirth-prevention bills that are pending in Congress — they lack the scope and urgency seen in Australia.

“If you ask which parts of the work in Australia can be done in or should be done in the U.S., the answer is all of it,” said Susannah Hopkins Leisher, a stillbirth parent, epidemiologist and assistant professor in the stillbirth research program at the University of Utah Health. “There’s no physical reason why we cannot do exactly what Australia has done.”

Australia’s goal, which has been complicated by the pandemic, is to, by 2025, reduce the country’s rate of stillbirths after 28 weeks by 20% from its 2020 rate. The national plan laid out the target, and it is up to each jurisdiction to determine how to implement it based on their local needs.

The most significant development came in 2019, when the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence — the headquarters for Australia’s stillbirth-prevention efforts — launched the core of its strategy, a checklist of five evidence-based priorities known as the Safer Baby Bundle. They include supporting pregnant patients to stop smoking; regular monitoring for signs that the fetus is not growing as expected, which is known as fetal growth restriction; explaining the importance of acting quickly if fetal movement changes or decreases; advising pregnant patients to go to sleep on their side after 28 weeks; and encouraging patients to talk to their doctors about when to deliver because in some cases that may be before their due date.

Officials estimate that at least half of all births in the country are covered by maternity services that have adopted the bundle, which focuses on preventing stillbirths after 28 weeks.

“These are babies whose lives you would expect to save because they would survive if they were born alive,” said Dr. David Ellwood, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Griffith University, director of maternal-fetal medicine at Gold Coast University Hospital and a co-director of the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence.

Australia wasn’t always a leader in stillbirth prevention.

In 2000, when the stillbirth rate in the U.S. was 3.3 per 1,000 total births, Australia’s was 3.7. A group of doctors, midwives and parents recognized the need to do more and began working on improving their data classification and collection to better understand the problem areas. By 2014, Australia published its first in-depth national report on stillbirth. Two years later, the medical journal The Lancet published the second report in a landmark series on stillbirths, and Australian researchers applied for the first grant from the government to create the stillbirth research center.

But full federal buy-in remained elusive.

As parent advocates, researchers, doctors and midwives worked to gain national support, they didn’t yet know they would find a champion in Keneally.

Keneally’s improbable journey began when she was born in Nevada to an American father and Australian mother. She grew up in Ohio, graduating from the University of Dayton before meeting the man who would become her husband and moving to Australia.

When she learned that her daughter, who she named Caroline, would be stillborn, she remembers thinking, “I’m smart. I’m educated. How did I let this happen? And why did nobody tell me this was a possible outcome?”

A few years later, in 2003, Keneally decided to enter politics. She was elected to the lower house of state parliament in New South Wales, of which Sydney is the capital. In Australia, newly elected members are expected to give a “first speech.” She was able to get through just one sentence about Caroline before starting to tear up.

As a legislator, Keneally didn’t think of tackling stillbirth as part of her job. There wasn’t any public discourse about preventing stillbirths or supporting families who’d had one. When Caroline was born still, all Keneally got was a book titled “When a Baby Dies.”

In 2009, Keneally became New South Wales’ first woman premier, a role similar to that of an American governor. Another woman who had suffered her own stillbirth and was starting a stillbirth foundation learned of Keneally’s experience. She wrote to Keneally and asked the premier to be the foundation’s patron.

What’s the point of being the first female premier, Keneally thought, if I can’t support this group?

Like the U.S., Australia had previously launched an awareness campaign that contributed to a staggering reduction in sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS. But there was no similar push for stillbirths.

“If we can figure out ways to reduce SIDS,” Keneally said, “surely it’s not beyond us to figure out ways to reduce stillbirth.”

She lost her seat after two years and took a break from politics, only to return six years later. In 2018, she was selected to serve as a senator at Australia’s federal level.

Keneally saw this as her second chance to fight for stillbirth prevention. In the short period between her election and her inaugural speech, she had put everything in place for a Senate inquiry into stillbirth.

In her address, Keneally declared stillbirth a national public health crisis. This time, she spoke at length about Caroline.

“When it comes to stillbirth prevention,” she said, “there are things that we know that we’re not telling parents, and there are things we don’t know, but we could, if we changed how we collected data and how we funded research.”

The day of her speech, March 27, 2018, she and her fellow senators established the Select Committee on Stillbirth Research and Education.

Things moved quickly over the next nine months. Keneally and other lawmakers traveled the country holding hearings, listening to testimony from grieving parents and writing up their findings in a report released that December.

“The culture of silence around stillbirth means that parents and families who experience it are less likely to be prepared to deal with the personal, social and financial consequences,” the report said. “This failure to regard stillbirth as a public health issue also has significant consequences for the level of funding available for research and education, and for public awareness of the social and economic costs to the community as a whole.”

It would be easy to swap the U.S. for Australia in many places throughout the report. Women of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds experienced double the rate of stillbirth of other Australian women; Black women in America are more than twice as likely as white women to have a stillbirth. Both countries faced a lack of coordinated research and corresponding funding, low autopsy rates following a stillbirth and poor public awareness of the problem.

The day after the report’s release, the Australian government announced that it would develop a national plan and pledged $7.2 million in funding for prevention. Nearly half was to go to education and awareness programs for women and their health care providers.

In the following months, government officials rolled out the Safer Baby Bundle and pledged another $26 million to support parents’ mental health after a loss.

Many in Australia see Keneally’s first speech as senator, in 2018, as the turning point for the country’s fight for stillbirth prevention. Her words forced the federal government to acknowledge the stillbirth crisis and launch the national action plan with bipartisan support.

Australia’s assistant minister for health and aged care, Ged Kearney, cited Keneally’s speech in an email to ProPublica where she noted that Australia has become a world leader in stillbirth awareness, prevention and supporting families after a loss.

“Kristina highlighted the power of women telling their story for positive change,” Kearney said, adding, “As a Labor Senator Kristina Keneally bravely shared her deeply personal story of her daughter Caroline who was stillborn in 1999. Like so many mothers, she helped pave the way for creating a more compassionate and inclusive society.”

Keneally, who is now CEO of Sydney Children’s Hospitals Foundation, said the number of stillbirths a day in Australia spurred the movement for change.

“Six babies a day,” Keneally said. “Once you hear that fact, you can’t unhear it.”

Australia’s leading stillbirth experts watched closely as the country moved closer to a unified effort. This was the moment for which they had been waiting.

“We had all the information needed, but that’s really what made it happen.” said Vicki Flenady, a perinatal epidemiologist, co-director of the Stillbirth Centre of Research Excellence based at the Mater Research Institute at the University of Queensland, and a lead author on The Lancet’s stillbirth series. “I don’t think there’s a person who could dispute that.”

Flenady and her co-director Ellwood had spent more than two decades focused on stillbirths. After establishing the center in 2017, they were now able to expand their team. As part of their work with the International Stillbirth Alliance, they reached out to other countries with a track record of innovation and evidence-based research: the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Ireland. They modeled the Safer Baby Bundle after a similar one in the U.K., though they added some elements.

In 2019, the state of Victoria, home to Melbourne, was the first to implement the Safer Baby Bundle. But 10 months into the program, the effort had to be paused for several months because of the pandemic, which forced other states to cancel their launches altogether.

“COVID was a major disruption. We stopped and started,” Flenady said.

Still, between 2019 and 2021, participating hospitals across Victoria were able to reduce their stillbirth rate by 21%. That improvement has yet to be seen at the national level.

A number of areas are still working on implementing the bundle. Westmead Hospital, one of Australia’s largest hospitals, planned to wrap that phase up last month. Like many hospitals, Westmead prominently displays the bundle’s key messages in the colorful posters and flyers hanging in patient rooms and in the hallways. They include easy-to-understand slogans such as, “Big or small. Your baby’s growth matters,” and, “Sleep on your side when baby’s inside.”

As patients at Westmead wait for their names to be called, a TV in the waiting room plays a video on stillbirth prevention, highlighting the importance of fetal movement. If a patient is concerned their baby’s movements have slowed down, they are instructed to come in to be seen within two hours. The patient’s chart gets a colorful sticker with a 16-point checklist of stillbirth risk factors.

Susan Heath, a senior clinical midwife at Westmead, came up with the idea for the stickers. Her office is tucked inside the hospital’s maternity wing, down a maze of hallways. As she makes the familiar walk to her desk, with her faded hospital badge bouncing against her navy blue scrubs, it’s clear she is a woman on a mission. The bundle gives doctors and midwives structure and uniform guidance, she said, and takes stillbirth out of the shadows. She reminds her staff of how making the practices a routine part of their job has the power to change their patients’ lives.

“You’re trying,” she said, “to help them prevent having the worst day of their life.”

Christine Andrews, a senior researcher at the Stillbirth Centre who is leading an evaluation of the program’s effectiveness, said the national stillbirth rate beyond 28 weeks has continued to slowly improve.

“It is going to take a while until we see the stillbirth rate across the whole entire country go down,” Andrews said. “We are anticipating that we’re going to start to see a shift in that rate soon.”

As officials wait to receive and standardize the data from hospitals and states, they are encouraged by a number of indicators.

For example, several states are reporting increases in the detection of babies that aren’t growing as they should, a major factor in many late-gestation stillbirths. Many also have seen an increase in the number of pregnant patients who stopped smoking. Health care providers also are more consistently offering post-stillbirth investigations, such as autopsies.

In addition to the Safer Baby Bundle, the national plan also calls for raising awareness and reducing racial disparities. The improvements it recommends for bereavement care are already gaining global attention.

To fulfill those directives, Australia has launched a “Still Six Lives” public awareness campaign, has implemented a national stillbirth clinical care standard and has spent two years developing a culturally inclusive version of the Safer Baby Bundle for First Nations, migrant and refugee communities. Those resources, which were recently released, incorporated cultural traditions and used terms like Stronger Bubba Born for the bundle and “sorry business babies,” which is how some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women refer to stillbirth. There are also audio versions for those who can’t or prefer not to read the information.

In May, nearly 50 people from the state of Queensland met in a large hotel conference room. Midwives, doctors and nurses sat at round tables with government officials, hospital administrators and maternal and infant health advocates. Some even wore their bright blue Safer Baby T-shirts.

One by one, they discussed their experiences implementing the Safer Baby Bundle. One midwifery group was able to get more than a third of its patients to stop smoking between their first visit and giving birth.

Officials from a hospital in one of the fastest-growing areas in the state discussed how they carefully monitored for fetal growth restriction.

And staff from another hospital, which serves many low-income and immigrant patients, described how 97% of pregnant patients who said their baby’s movements had decreased were seen for additional monitoring within two hours of voicing their concern.

As the midwives, nurses and doctors ticked off the progress they were seeing, they also discussed the fear of unintended consequences: higher rates of premature births or increased admissions to neonatal intensive care units. But neither, they said, has materialized.

“The bundle isn’t causing any harm and may be improving other outcomes, like reducing early-term birth,” Flenady said. “I think it really shows a lot of positive impact.”

As far behind as the U.S. is in prioritizing stillbirth prevention, there is still hope.

Dr. Bob Silver, who co-authored a study that estimated that nearly 1 in 4 stillbirths are potentially preventable, has looked to the international community as a model. Now, he and Leisher — the University of Utah epidemiologist and stillbirth parent — are working to create one of the first stillbirth research and prevention centers in the U.S. in partnership with stillbirth leaders from Australia and other countries. They hope to launch next year.

“There’s no question that Australia has done a better job than we have,” said Silver, who is also chair of the University of Utah Health obstetrics and gynecology department. “Part of it is just highlighting it and paying attention to it.”

It’s hard to know what parts of Australia’s strategy are making a difference — the bundle as a whole, just certain elements of it, the increased stillbirth awareness across the country, or some combination of those things. Not every component has been proven to decrease stillbirth.

The lack of U.S. research on the issue has made some cautious to adopt the bundle, Silver said, but it is clear the U.S. can and should do more.

There comes a point when an issue is so critical, Silver said, that people have to do the best they can with the information that they have. The U.S. has done that with other problems, such as maternal mortality, he said, though many of the tactics used to combat that problem have not been proven scientifically.

“But we’ve decided this problem is so bad, we’re going to try the things that we think are most likely to be helpful,” Silver said.

After more than 30 years of working on stillbirth prevention, Silver said the U.S. may be at a turning point. Parents’ voices are getting louder and starting to reach lawmakers. More doctors are affirming that stillbirths are not inevitable. And pressure is mounting on federal institutions to do more.

Of the two stillbirth prevention bills in Congress, one already sailed through the Senate. The second bill, the Stillbirth Health Improvement and Education for Autumn Act, includes features that also appeared in Australia’s plan, such as improving data, increasing awareness and providing support for autopsies.

And after many years, the National Institutes of Health has turned its focus back to stillbirths. In March, it released a report with a series of recommendations to reduce the nation’s stillbirth rate that mirror ProPublica’s reporting about some of the causes of the crisis. Since then, it has launched additional groups to begin to tackle three critical angles: prevention, data and bereavement. Silver co-chairs the prevention group.

In November, more than 100 doctors, parents and advocates gathered for a symposium in New York City to discuss everything from improving bereavement care in the U.S to tackling racial disparities in stillbirth. In 2022, after taking a page out of the U.K.’s book, the city’s Mount Sinai Hospital opened the first Rainbow Clinic in the U.S., which employs specific protocols to care for people who have had a stillbirth.

But given the financial resources in the U.S. and the academic capacity at American universities and research institutions, Leisher and others said federal and state governments aren’t doing nearly enough.

“The U.S. is not pulling its weight in relation either to our burden or to the resources that we have at our disposal,” she said. “We’ve got a lot of babies dying, and we’ve got a really bad imbalance of who those babies are as well. And yet we look at a country with a much smaller number of stillbirths who is leading the world.”

“We can do more. Much more. We’re just not,” she added. “It’s unacceptable.”

Share This Post

-

Seeds: The Good, The Bad, And The Not-Really-Seeds!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Doctors are great at saving lives like mine. I’m a two time survivor of colon cancer and have recently been diagnosed with Chron’s disease at 62. No one is the health system can or is prepared to tell me an appropriate diet to follow or what to avoid. Can you?❞

Congratulations on the survivorship!

As to Crohn’s, that’s indeed quite a pain, isn’t it? In some ways, a good diet for Crohn’s is the same as a good diet for most other people, with one major exception: fiber

…and unfortunately, that changes everything, in terms of a whole-foods majority plant-based diet.

What stays the same:

- You still ideally want to eat a lot of plants

- You definitely want to avoid meat and dairy in general

- Eating fish is still usually* fine, same with eggs

- Get plenty of water

What needs to change:

- Consider swapping grains for potatoes or pasta (at least: avoid grains)

- Peel vegetables that are peelable; discard the peel or use it to make stock

- Consider steaming fruit and veg for easier digestion

- Skip spicy foods (moderate spices, like ginger, turmeric, and black pepper, are usually fine in moderation)

Much of this latter list is opposite to the advice for people without Crohn’s Disease.

*A good practice, by the way, is to keep a food journal. There are apps that you can get for free, or you can do it the old-fashioned way on paper if prefer.

But the important part is: make a note not just of what you ate, but also of how you felt afterwards. That way, you can start to get a picture of patterns, and what’s working (or not) for you, and build up a more personalized set of guidelines than anyone else could give to you.

We hope the above pointers at least help you get going on the right foot, though!

❝Why do baked goods and deep fried foods all of a sudden become intolerable? I used to b able to ingest bakery foods and fried foods. Lately I developed an extreme allergy to Kiwi… what else should I “fear”❞

About the baked goods and the deep-fried foods, it’s hard to say without more information! It could be something in the ingredients or the method, and the intolerance could be any number of symptoms that we don’t know. Certainly, pastries and deep-fried foods are not generally substantial parts of a healthy diet, of course!

Kiwi, on the other hand, we can answer… Or rather, we can direct you to today’s “What’s happening in the health world” section below, as there is news on that front!

We turn the tables and ask you a question!

We’ll then talk about this tomorrow:

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Yes, you still need to use sunscreen, despite what you’ve heard on TikTok

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Summer is nearly here. But rather than getting out the sunscreen, some TikTokers are urging followers to chuck it out and go sunscreen-free.

They claim it’s healthier to forgo sunscreen to get the full benefits of sunshine.

Here’s the science really says.

Karolina Grabowska/Pexels How does sunscreen work?

Because of Australia’s extreme UV environment, most people with pale to olive skin or other risk factors for skin cancer need to protect themselves. Applying sunscreen is a key method of protecting areas not easily covered by clothes.

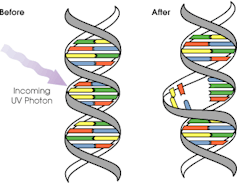

Sunscreen works by absorbing or scattering UV rays before they can enter your skin and damage DNA or supportive structures such as collagen.

When UV particles hit DNA, the excess energy can damage our DNA. This damage can be repaired, but if the cell divides before the mistake is fixed, it causes a mutation that can lead to skin cancers.

The energy from a particle of UV (a photon) causes DNA strands to break apart and reconnect incorrectly. This causes a bump in the DNA strand that makes it difficult to copy accurately and can introduce mutations. NASA/David Herring The most common skin cancers are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Melanoma is less common, but is the most likely to spread around the body; this process is called metastasis.

Two in three Australians will have at least one skin cancer in their lifetime, and they make up 80% of all cancers in Australia.

Around 99% of skin cancers in Australia are caused by excessive exposure to UV radiation.

Excessive exposure to UV radiation also affects the appearance of your skin. UVA rays are able to penetrate deep into the skin, where they break down supportive structures such as elastin and collagen.

This causes signs of premature ageing, such as deep wrinkling, brown or white blotches, and broken capillaries.

Sunscreen can help prevent skin cancers

Used consistently, sunscreen reduces your risk of skin cancer and slows skin ageing.

In a Queensland study, participants either used sunscreen daily for almost five years, or continued their usual use.

At the end of five years, the daily-use group had reduced their risk of squamous cell carcinoma by 40% compared to the other group.

Ten years later, the daily use group had reduced their risk of invasive melanoma by 73%

Does sunscreen block the health-promoting properties of sunlight?

The answer is a bit more complicated, and involves personalised risk versus benefit trade-offs.

First, the good news: there are many health benefits of spending time in the sun that don’t rely on exposure to UV radiation and aren’t affected by sunscreen use.

Sunscreen only filters UV rays, not all light. Ron Lach/Pexels Sunscreen only filters UV rays, not visible light or infrared light (which we feel as heat). And importantly, some of the benefits of sunlight are obtained via the eyes.

Visible light improves mood and regulates circadian rhythm (which influences your sleep-wake cycle), and probably reduces myopia (short-sightedness) in children.

Infrared light is being investigated as a treatment for several skin, neurological, psychiatric and autoimmune disorders.

So what is the benefit of exposing skin to UV radiation?

Exposing the skin to the sun produces vitamin D, which is critical for healthy bones and muscles.

Vitamin D deficiency is surprisingly common among Australians, peaking in Victoria at 49% in winter and being lowest in Queensland at 6% in summer.

Luckily, people who are careful about sun protection can avoid vitamin D deficiency by taking a supplement.

Exposing the skin to UV radiation might have benefits independent of vitamin D production, but these are not proven. It might reduce the risk of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis or cause release of a chemical that could reduce blood pressure. However, there is not enough detail about these benefits to know whether sunscreen would be a problem.

What does this mean for you?

There are some benefits of exposing the skin to UV radiation that might be blunted by sunscreen. Whether it’s worth foregoing those benefits to avoid skin cancer depends on how susceptible you are to skin cancer.

If you have pale skin or other factors that increase you risk of skin cancer, you should aim to apply sunscreen daily on all days when the UV index is forecast to reach 3.

If you have darker skin that rarely or never burns, you can go without daily sunscreen – although you will still need protection during extended times outdoors.

For now, the balance of evidence suggests it’s better for people who are susceptible to skin cancer to continue with sun protection practices, with vitamin D supplementation if needed.

Katie Lee, PhD Candidate, Dermatology Research Centre, The University of Queensland and Rachel Neale, Principal research fellow, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Body Image Dissatisfaction/Appreciation Across The Ages

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Every second news article about body image issues is talking about teens and social media use, but science tells a different story.

A large (n=1,327) study of people of mixed genders aged 16–88 examined matters relating to people’s body image, expecting…

❝We hypothesized that body dissatisfaction and importance of appearance would be higher in women than in men, that body dissatisfaction would remain stable across age in women, and that importance of appearance would be lower in older women compared to younger women. Body appreciation was predicted to be higher in men than in women.❞

As they discovered, only half of that turned out to be true:

❝In line with our hypotheses, body dissatisfaction was higher in women than in men and was unaffected by age in women, and importance of appearance was higher in women than in men.

However, only in men did age predict a lower level of the importance of appearance. Compared to men, women stated that they would invest more hours of their lives to achieve their ideal appearance.

Contrary to our assumption, body appreciation improved and was higher in women across all ages than in men.❞

You can read the study in full here:

That’s a lot of information, and we don’t have the space to go into all parts of it here, fascinating as that would be. So we’re going to put two pieces of information (from the above) next to each other:

- body dissatisfaction was higher in women than in men and was unaffected by age in women

- body appreciation improved and was higher in women across all ages than in men

…and resolve this apparent paradox.

Dissatisfied appreciation

How is it that women are both more dissatisfied with, and yet also more appreciative of, their bodies?

The answer is that we can have positive and negative feelings about the same thing, without them cancelling each other out. In short, simply, feeling more feelings about it.

Whether the gender-related disparity in this case comes more from hormones or society could be vigorously debated, but chances are, it’s both. And, for our gentleman-readers, note that the principle still applies to you, even if scaled down on average.

Call to action:

- be aware of the negative feelings of body dissatisfaction

- focus on the positive feelings of body appreciation

While in theory both could motivate us to action, in reality, the former will tend to inform us (about what we might wish to change), while the latter will actually motivate us in a useful way (to do something positive about it).

This is because the negative feelings about body image tend to be largely based in shame, and shame is a useless motivator (i.e., it simply doesn’t work) when it comes to taking positive actions:

Why Shame Only Works Negatively

You can’t hate yourself into a body you love

That may sound like a wishy-washy platitude, but given the evidence on how shame works (and doesn’t), it’s true.

Instead, once you’ve identified the things about your body with which you’re dissatisfied, you can then assess:

- what can reasonably be changed

- whether it is important enough to you to change it

- how to go about usefully changing it

While weight issues are perhaps the most commonly-discussed body image consideration, to the point that often all others get forgotten, let’s look at something that’s generally more specific to adults, and also a very common cause of distress for women and men alike: hair loss/thinning.

If your hair is just starting to thin and fall, then if this bothers you, there’s a lot that can be done about it quite easily, but (and this is important) you have to love yourself enough to actually do it. Merely feeling miserable about it, and perhaps like you don’t deserve better, or that it is somehow a personal failing on your part, will not help.

If your hair has been gone for years, then chances are you’ve made your peace with this by now, and might not even take it back if a fairy godmother came along and offered to restore it magically. On the other hand, let’s say that you’re just coming out the other end of a 10-year-long depression, and perhaps you let a lot of things go that you now wish you hadn’t, and maybe your hair is one of them. In this case, now you need to decide whether getting implants (likely the only solution at this late stage) is worth it.

Note that in both cases, whatever the starting point and whether the path ahead is easy or hard, the person who has dissatisfaction and/but still values themself and their body will get what they need.

In contrast, the person who has dissatisfaction and does not value themself and their body, will languish.

The person without dissatisfaction, of course, probably already has what they need.

In short: identification of dissatisfaction + love and appreciation of oneself and one’s body → motivation to usefully take action (out of love, not hate)

Now, dear reader, apply the same thinking to whatever body image issues you may have, and take it from there!

Embodiment

A quick note in closing: if you are a person with no body dissatisfactions, there are two main possible reasons:

- You are genuinely happy with your body in all respects. Congratulations!

- You have disassociated from your body to such an extent that it’s become a mere vehicle to you and you don’t care about it.

This latter may seem like a Zen-level win, but in fact it’s a warning sign for depression, so please do examine that even if you don’t “feel” depressed (depression is often characterized by a lack of feelings), perhaps by taking the (very quick) free PHQ9 Test ← under 2 minutes; immediate results; industry-standard diagnostic tool

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What are the most common symptoms of menopause? And which can hormone therapy treat?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Despite decades of research, navigating menopause seems to have become harder – with conflicting information on the internet, in the media, and from health care providers and researchers.

Adding to the uncertainty, a recent series in the Lancet medical journal challenged some beliefs about the symptoms of menopause and which ones menopausal hormone therapy (also known as hormone replacement therapy) can realistically alleviate.

So what symptoms reliably indicate the start of perimenopause or menopause? And which symptoms can menopause hormone therapy help with? Here’s what the evidence says.

Remind me, what exactly is menopause?

Menopause, simply put, is complete loss of female fertility.

Menopause is traditionally defined as the final menstrual period of a woman (or person female at birth) who previously menstruated. Menopause is diagnosed after 12 months of no further bleeding (unless you’ve had your ovaries removed, which is surgically induced menopause).

Perimenopause starts when menstrual cycles first vary in length by seven or more days, and ends when there has been no bleeding for 12 months.

Both perimenopause and menopause are hard to identify if a person has had a hysterectomy but their ovaries remain, or if natural menstruation is suppressed by a treatment (such as hormonal contraception) or a health condition (such as an eating disorder).

What are the most common symptoms of menopause?

Our study of the highest quality menopause-care guidelines found the internationally recognised symptoms of the perimenopause and menopause are:

- hot flushes and night sweats (known as vasomotor symptoms)

- disturbed sleep

- musculoskeletal pain

- decreased sexual function or desire

- vaginal dryness and irritation

- mood disturbance (low mood, mood changes or depressive symptoms) but not clinical depression.

However, none of these symptoms are menopause-specific, meaning they could have other causes.

In our study of Australian women, 38% of pre-menopausal women, 67% of perimenopausal women and 74% of post-menopausal women aged under 55 experienced hot flushes and/or night sweats.

But the severity of these symptoms varies greatly. Only 2.8% of pre-menopausal women reported moderate to severely bothersome hot flushes and night sweats symptoms, compared with 17.1% of perimenopausal women and 28.5% of post-menopausal women aged under 55.

So bothersome hot flushes and night sweats appear a reliable indicator of perimenopause and menopause – but they’re not the only symptoms. Nor are hot flushes and night sweats a western society phenomenon, as has been suggested. Women in Asian countries are similarly affected.

You don’t need to have night sweats or hot flushes to be menopausal.

Maridav/ShutterstockDepressive symptoms and anxiety are also often linked to menopause but they’re less menopause-specific than hot flushes and night sweats, as they’re common across the entire adult life span.

The most robust guidelines do not stipulate women must have hot flushes or night sweats to be considered as having perimenopausal or post-menopausal symptoms. They acknowledge that new mood disturbances may be a primary manifestation of menopausal hormonal changes.

The extent to which menopausal hormone changes impact memory, concentration and problem solving (frequently talked about as “brain fog”) is uncertain. Some studies suggest perimenopause may impair verbal memory and resolve as women transition through menopause. But strategic thinking and planning (executive brain function) have not been shown to change.

Who might benefit from hormone therapy?

The Lancet papers suggest menopause hormone therapy alleviates hot flushes and night sweats, but the likelihood of it improving sleep, mood or “brain fog” is limited to those bothered by vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats).

In contrast, the highest quality clinical guidelines consistently identify both vasomotor symptoms and mood disturbances associated with menopause as reasons for menopause hormone therapy. In other words, you don’t need to have hot flushes or night sweats to be prescribed menopause hormone therapy.

Often, menopause hormone therapy is prescribed alongside a topical vaginal oestrogen to treat vaginal symptoms (dryness, irritation or urinary frequency).

You don’t need to experience hot flushes and night sweats to take hormone therapy.

Monkey Business Images/ShutterstockHowever, none of these guidelines recommend menopause hormone therapy for cognitive symptoms often talked about as “brain fog”.

Despite musculoskeletal pain being the most common menopausal symptom in some populations, the effectiveness of menopause hormone therapy for this specific symptoms still needs to be studied.

Some guidelines, such as an Australian endorsed guideline, support menopause hormone therapy for the prevention of osteoporosis and fracture, but not for the prevention of any other disease.

What are the risks?

The greatest concerns about menopause hormone therapy have been about breast cancer and an increased risk of a deep vein clot which might cause a lung clot.

Oestrogen-only menopause hormone therapy is consistently considered to cause little or no change in breast cancer risk.

Oestrogen taken with a progestogen, which is required for women who have not had a hysterectomy, has been associated with a small increase in the risk of breast cancer, although any risk appears to vary according to the type of therapy used, the dose and duration of use.

Oestrogen taken orally has also been associated with an increased risk of a deep vein clot, although the risk varies according to the formulation used. This risk is avoided by using estrogen patches or gels prescribed at standard doses

What if I don’t want hormone therapy?

If you can’t or don’t want to take menopause hormone therapy, there are also effective non-hormonal prescription therapies available for troublesome hot flushes and night sweats.

In Australia, most of these options are “off-label”, although the new medication fezolinetant has just been approved in Australia for postmenopausal hot flushes and night sweats, and is expected to be available by mid-year. Fezolinetant, taken as a tablet, acts in the brain to stop the chemical neurokinin 3 triggering an inappropriate body heat response (flush and/or sweat).

Unfortunately, most over-the-counter treatments promoted for menopause are either ineffective or unproven. However, cognitive behaviour therapy and hypnosis may provide symptom relief.

The Australasian Menopause Society has useful menopause fact sheets and a find-a-doctor page. The Practitioner Toolkit for Managing Menopause is also freely available.

Susan Davis, Chair of Women’s Health, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: