Why is cancer called cancer? We need to go back to Greco-Roman times for the answer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One of the earliest descriptions of someone with cancer comes from the fourth century BC. Satyrus, tyrant of the city of Heracleia on the Black Sea, developed a cancer between his groin and scrotum. As the cancer spread, Satyrus had ever greater pains. He was unable to sleep and had convulsions.

Advanced cancers in that part of the body were regarded as inoperable, and there were no drugs strong enough to alleviate the agony. So doctors could do nothing. Eventually, the cancer took Satyrus’ life at the age of 65.

Cancer was already well known in this period. A text written in the late fifth or early fourth century BC, called Diseases of Women, described how breast cancer develops:

hard growths form […] out of them hidden cancers develop […] pains shoot up from the patients’ breasts to their throats, and around their shoulder blades […] such patients become thin through their whole body […] breathing decreases, the sense of smell is lost […]

Other medical works of this period describe different sorts of cancers. A woman from the Greek city of Abdera died from a cancer of the chest; a man with throat cancer survived after his doctor burned away the tumour.

Where does the word ‘cancer’ come from?

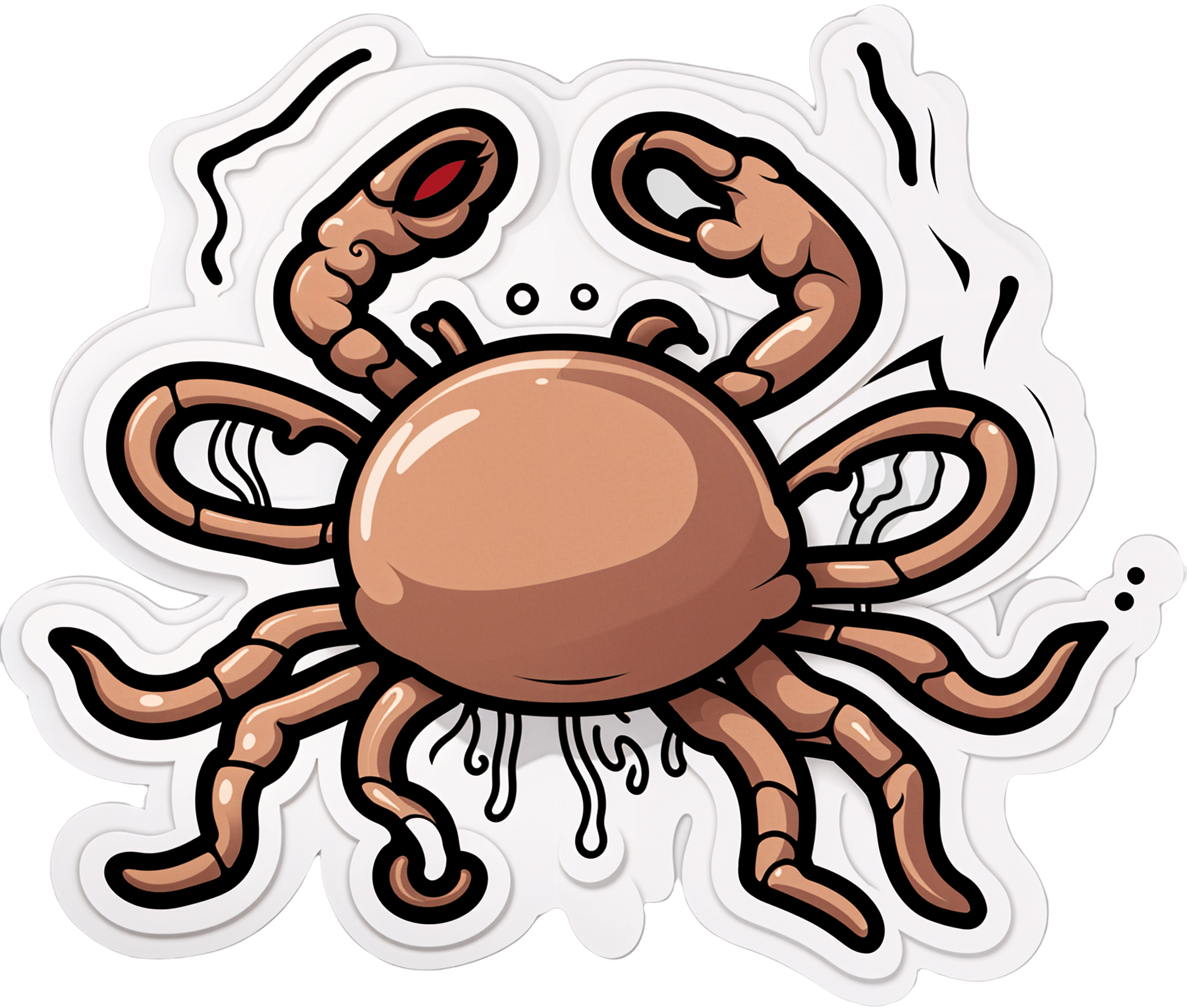

The word cancer comes from the same era. In the late fifth and early fourth century BC, doctors were using the word karkinos – the ancient Greek word for crab – to describe malignant tumours. Later, when Latin-speaking doctors described the same disease, they used the Latin word for crab: cancer. So, the name stuck.

Even in ancient times, people wondered why doctors named the disease after an animal. One explanation was the crab is an aggressive animal, just as cancer can be an aggressive disease; another explanation was the crab can grip one part of a person’s body with its claws and be difficult to remove, just as cancer can be difficult to remove once it has developed. Others thought it was because of the appearance of the tumour.

The physician Galen (129-216 AD) described breast cancer in his work A Method of Medicine to Glaucon, and compared the form of the tumour to the form of a crab:

We have often seen in the breasts a tumour exactly like a crab. Just as that animal has feet on either side of its body, so too in this disease the veins of the unnatural swelling are stretched out on either side, creating a form similar to a crab.

Not everyone agreed what caused cancer

In the Greco-Roman period, there were different opinions about the cause of cancer.

According to a widespread ancient medical theory, the body has four humours: blood, yellow bile, phlegm and black bile. These four humours need to be kept in a state of balance, otherwise a person becomes sick. If a person suffered from an excess of black bile, it was thought this would eventually lead to cancer.

The physician Erasistratus, who lived from around 315 to 240 BC, disagreed. However, so far as we know, he did not offer an alternative explanation.

How was cancer treated?

Cancer was treated in a range of different ways. It was thought that cancers in their early stages could be cured using medications.

These included drugs derived from plants (such as cucumber, narcissus bulb, castor bean, bitter vetch, cabbage); animals (such as the ash of a crab); and metals (such as arsenic).

Galen claimed that by using this sort of medication, and repeatedly purging his patients with emetics or enemas, he was sometimes successful at making emerging cancers disappear. He said the same treatment sometimes prevented more advanced cancers from continuing to grow. However, he also said surgery is necessary if these medications do not work.

Surgery was usually avoided as patients tended to die from blood loss. The most successful operations were on cancers of the tip of the breast. Leonidas, a physician who lived in the second and third century AD, described his method, which involved cauterising (burning):

I usually operate in cases where the tumours do not extend into the chest […] When the patient has been placed on her back, I incise the healthy area of the breast above the tumour and then cauterize the incision until scabs form and the bleeding is stanched. Then I incise again, marking out the area as I cut deeply into the breast, and again I cauterize. I do this [incising and cauterizing] quite often […] This way the bleeding is not dangerous. After the excision is complete I again cauterize the entire area until it is dessicated.

Cancer was generally regarded as an incurable disease, and so it was feared. Some people with cancer, such as the poet Silius Italicus (26-102 AD), died by suicide to end the torment.

Patients would also pray to the gods for hope of a cure. An example of this is Innocentia, an aristocratic lady who lived in Carthage (in modern-day Tunisia) in the fifth century AD. She told her doctor divine intervention had cured her breast cancer, though her doctor did not believe her.

From the past into the future

We began with Satyrus, a tyrant in the fourth century BC. In the 2,400 years or so since then, much has changed in our knowledge of what causes cancer, how to prevent it and how to treat it. We also know there are more than 200 different types of cancer. Some people’s cancers are so successfully managed, they go on to live long lives.

But there is still no general “cure for cancer”, a disease that about one in five people develop in their lifetime. In 2022 alone, there were about 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer deaths globally. We clearly have a long way to go.

Konstantine Panegyres, McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow, Historical and Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Unlock Your Air-Fryer’s Potential!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Unlock Your Air-Fryer’s Potential!

You know what they say:

“you get out of it what you put in”

…and in the case of an air-fryer, that’s very true!

More seriously:

A lot of people buy an air fryer for its health benefits and convenience, make fries a couple of times, and then mostly let it gather dust. But for those who want to unlock its potential, there’s plenty more it can do!

Let’s go over the basics first…

Isn’t it just a tiny convection oven?

Mechanically, yes. But the reason that it can be used to “air-fry” food rather than merely bake or roast the food is because of its tiny size allowing for much more rapid cooking at high temperatures.

On which note… If you’re shopping for an air-fryer:

- First of all, congratulations! You’re going to love it.

- Secondly: bigger is not better. If you go over more than about 4 liters capacity, then you don’t have an air-fryer; you have a convection oven. Which is great and all, but probably not what you wanted.

Are there health benefits beyond using less oil?

It also creates much less acrylamide than deep-frying starchy foods does. The jury is out on the health risks of acrylamide, but we can say with confidence: it’s not exactly a health food.

I tried it, but the food doesn’t cook or just burns!

The usual reason for this is either over-packing the fryer compartment (air needs to be able to circulate!), or not coating the contents in oil. The oil only needs to be a super-thin layer, but it does need to be there, or else again, you’re just baking things.

Two ways to get a super thin layer of oil on your food:

- (works for anything you can air-fry) spray the food with oil. You can buy spray-on oils at the grocery store (Fry-light and similar brands are great), or put oil in little spray bottle (of the kind that you might buy for haircare) yourself.

- (works with anything that can be shaken vigorously without harming it, e.g. root vegetables) chop the food, and put it in a tub (or a pan with a lid) with about a tablespoon of olive oil. Don’t worry if that looks like it’s not nearly enough—it will be! Now’s a great time to add your seasonings* too, by the way. Put the lid on, and holding the lid firmly in place, shake the tub/pan/whatever vigorously. Open it, and you’ll find the oil has now distributed itself into a very thin layer all over the food.

*About those seasonings…

Obviously not everything will go with everything, but some very healthful seasonings to consider adding are:

- Garlic minced/granules/powder (great for the heart and immune health)

- Black pepper (boosts absorption of other nutrients, and provides more benefits of its own than we can list here)

- Turmeric (slows aging and has anti-cancer properties)

- Cinnamon (great for the heart and has anti-inflammatory properties)

Garlic and black pepper can go with almost anything (and in this writer’s house, they usually do!)

Turmeric has a sweet nutty taste, and will add its color anything it touches. So if you want beautiful golden fries, perfect! If you don’t want yellow eggplant, maybe skip it.

Cinnamon is, of course, great as part of breakfast and dessert dishes

On which note, things most people don’t think of air-frying:

- Breakfast frittata—the healthy way!

- Omelets—no more accidental scrambled egg and you don’t have to babysit it! Just take out the tray that things normally sit on, and build it directly onto the (spray-oiled) bottom of the air-fryer pan. If you’re worried it’ll burn: a) it won’t, because the heat is coming from above, not below b) you can always use greaseproof paper or even a small heatproof plate

- French toast—again with no cooking skills required

- Fish cakes—make the patties as normal, spray-oil and lightly bread them

- Cauliflower bites—spray oil or do the pan-jiggle we described; for seasonings, we recommend adding smoked paprika and, if you like heat, your preferred kind of hot pepper! These are delicious, and an amazing healthy snack that feels like junk food.

- Falafel—make the balls as usual, spray-oil (do not jiggle violently; they won’t have the structural integrity for that) and air-fry!

- Calamari (vegan option: onion rings!)—cut the squid (or onions) into rings, and lightly coat in batter and refrigerate for about an hour before air-frying at the highest heat your fryer does. This is critical, because air-fryers don’t like wet things, and if you don’t refrigerate it and then use a high heat, the batter will just drip, and you don’t want that. But with those two tips, it’ll work just great.

Want more ideas?

Check out EatingWell’s 65+ Healthy Air-Fryer Recipes ← the recipes are right there, no need to fight one’s way to them in any fashion!

Share This Post

-

Mango vs Guava – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing mango to guava, we picked the guava.

Why?

Looking at macros first, these two fruits are about equal on carbs (nominally mango has more, but it’s by a truly tiny margin), while guava has more than 3x the protein and more than 3x the fiber. A clear win for guava.

In terms of vitamins, mango has more of vitamins A, E, and K, while guava has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B7, B9, and C. Another win for guava.

In the category of minerals, mango is not higher in any minerals, while guava is higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc.

In short, enjoy both; both are healthy. But if you’re choosing one, there’s a clear winner here, and it’s guava.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Meditation for Fidgety Skeptics – by Dan Harris

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you already meditate regularly, this book isn’t aimed at you (though you may learn a thing or two anyway—this reviewer, who has practiced meditation for the past 30 years, learned a thing!).

However, if you’re—as the title suggests—someone who hasn’t so far been inclined towards meditation, you could get the most out of this one. We’ll say more on this (obviously), but first, there’s one other group that may benefit from this book:

If you have already practiced meditation, and/or already understand and want its benefits, but never really made it stick as a habit.

Now, onto what you’ll get:

- A fair scientific overview of meditation as an increasingly evidence-based way to reduce stress and increase both happiness and productivity

- A good grounding in what meditation is and isn’t

- A how-to guide for building up a consistent meditation habit that won’t get kiboshed when you have a particularly hectic day—or a cold.

- An assortment of very common (and some less common) meditative practices to try

- Some great auxiliary tools to build cognitive restructuring into your meditation

We don’t usually cite other people’s reviews, but we love that one Amazon reviewer wrote:

❝I am 3 weeks into daily meditation practice, and I already notice that I am no longer constantly wishing for undercarriage rocket launchers while driving. I will always think your driving sucks, but I no longer wish you a violent death because of it. Yes, I live in Boston❞

Bottom line: if you’re not already meditating daily, this is definitely a book for you. And if you are, you may learn a thing or two anyway!

Click here to get your copy of Meditation For Fidgety Skeptics from Amazon today!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Blind Spots – by Dr. Marty Makary

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From the time the US recommended not giving peanuts to infants for the first three years of life “in order to avoid peanut allergies” (whereupon non-exposure to peanuts early in life led to, instead, an increase in peanut allergies and anaphylactic incidents), to the time the US recommended not taking HRT on the strength of the claim that “HRT causes breast cancer” (whereupon the reduced popularity of HRT led to, instead, an increase in breast cancer incidence and mortality), to many other such incidents of very bad public advice being given on the strength of a single badly-misrepresented study (for each respective thing), Dr. Makary puts the spotlight on what went wrong.

This is important, because this is not just a book of outrage, exclaiming “how could this happen?!”, but rather instead, is a book of inquisition, asking “how did this happen?”, in such a way that we the reader can spot similar patterns going forwards.

Oftentimes, this is a simple matter of having a basic understanding of statistics, and checking sources to see if the dataset really supports what the headlines are claiming—and indeed, whether sometimes it suggests rather the opposite.

The style is a little on the sensationalist side, but it’s well-supported with sound arguments, good science, and clear mathematics.

Bottom line: if you’d like to improve your scientific literacy, this book is an excellent illustrative guide.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

I’ve been given opioids after surgery to take at home. What do I need to know?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Opioids are commonly prescribed when you’re discharged from hospital after surgery to help manage pain at home.

These strong painkillers may have unwanted side effects or harms, such as constipation, drowsiness or the risk of dependence.

However, there are steps you can take to minimise those harms and use opioids more safely as you recover from surgery.

Flystock/Shutterstock Which types of opioids are most common?

The most commonly prescribed opioids after surgery in Australia are oxycodone (brand names include Endone, OxyNorm) and tapentadol (Palexia).

In fact, about half of new oxycodone prescriptions in Australia occur after a recent hospital visit.

Most commonly, people will be given immediate-release opioids for their pain. These are quick-acting and are used to manage short-term pain.

Because they work quickly, their dose can be easily adjusted to manage current pain levels. Your doctor will provide instructions on how to adjust the dosage based on your pain levels.

Then there are slow-release opioids, which are specially formulated to slowly release the dose over about half to a full day. These may have “sustained-release”, “controlled-release” or “extended-release” on the box.

Slow-release formulations are primarily used for chronic or long-term pain. The slow-release form means the medicine does not have to be taken as often. However, it takes longer to have an effect compared with immediate-release, so it is not commonly used after surgery.

Controlling your pain after surgery is important. This allows you get up and start moving sooner, and recover faster. Moving around sooner after surgery prevents muscle wasting and harms associated with immobility, such as bed sores and blood clots.

Everyone’s pain levels and needs for pain medicines are different. Pain levels also decrease as your surgical wound heals, so you may need to take less of your medicine as you recover.

But there are also risks

As mentioned above, side effects of opioids include constipation and feeling drowsy or nauseous. The drowsiness can also make you more likely to fall over.

Opioids prescribed to manage pain at home after surgery are usually prescribed for short-term use.

But up to one in ten Australians still take them up to four months after surgery. One study found people didn’t know how to safely stop taking opioids.

Such long-term opioid use may lead to dependence and overdose. It can also reduce the medicine’s effectiveness. That’s because your body becomes used to the opioid and needs more of it to have the same effect.

Dependency and side effects are also more common with slow-release opioids than immediate-release opioids. This is because people are usually on slow-release opioids for longer.

Then there are concerns about “leftover” opioids. One study found 40% of participants were prescribed more than twice the amount they needed.

This results in unused opioids at home, which can be dangerous to the person and their family. Storing leftover opioids at home increases the risk of taking too much, sharing with others inappropriately, and using without doctor supervision.

Don’t stockpile your leftover opioids in your medicine cupboard. Take them to your pharmacy for safe disposal. Archer Photo/Shutterstock How to mimimise the risks

Before using opioids, speak to your doctor or pharmacist about using over-the-counter pain medicines such as paracetamol or anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen (for example, Nurofen, Brufen) or diclofenac (for example, Voltaren, Fenac).

These can be quite effective at controlling pain and will lessen your need for opioids. They can often be used instead of opioids, but in some cases a combination of both is needed.

Other techniques to manage pain include physiotherapy, exercise, heat packs or ice packs. Speak to your doctor or pharmacist to discuss which techniques would benefit you the most.

However, if you do need opioids, there are some ways to make sure you use them safely and effectively:

- ask for immediate-release rather than slow-release opioids to lower your risk of side effects

- do not drink alcohol or take sleeping tablets while on opioids. This can increase any drowsiness, and lead to reduced alertness and slower breathing

- as you may be at higher risk of falls, remove trip hazards from your home and make sure you can safely get up off the sofa or bed and to the bathroom or kitchen

- before starting opioids, have a plan in place with your doctor or pharmacist about how and when to stop taking them. Opioids after surgery are ideally taken at the lowest possible dose for the shortest length of time.

A heat pack may help with pain relief, so you end up using fewer painkillers. New Africa/Shutterstock If you’re concerned about side effects

If you are concerned about side effects while taking opioids, speak to your pharmacist or doctor. Side effects include:

- constipation – your pharmacist will be able to give you lifestyle advice and recommend laxatives

- drowsiness – do not drive or operate heavy machinery. If you’re trying to stay awake during the day, but keep falling asleep, your dose may be too high and you should contact your doctor

- weakness and slowed breathing – this may be a sign of a more serious side effect such as respiratory depression which requires medical attention. Contact your doctor immediately.

If you’re having trouble stopping opioids

Talk to your doctor or pharmacist if you’re having trouble stopping opioids. They can give you alternatives to manage the pain and provide advice on gradually lowering your dose.

You may experience withdrawal effects, such as agitation, anxiety and insomnia, but your doctor and pharmacist can help you manage these.

How about leftover opioids?

After you have finished using opioids, take any leftovers to your local pharmacy to dispose of them safely, free of charge.

Do not share opioids with others and keep them away from others in the house who do not need them, as opioids can cause unintended harms if not used under the supervision of a medical professional. This could include accidental ingestion by children.

For more information, speak to your pharmacist or doctor. Choosing Wisely Australia also has free online information about managing pain and opioid medicines.

Katelyn Jauregui, PhD Candidate and Clinical Pharmacist, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney; Asad Patanwala, Professor, Sydney School of Pharmacy, University of Sydney; Jonathan Penm, Senior lecturer, School of Pharmacy, University of Sydney, and Shania Liu, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Alberta

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Foods For Managing Hypothyroidism (incl. Hashimoto’s)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Foods for Managing Hypothyroidism

For any unfamiliar, hypothyroidism is the condition of having an underactive thyroid gland. The thyroid gland lives at the base of the front of your neck, and, as the name suggests, it makes and stores thyroid hormones. Those are important for many systems in the body, and a shortage typically causes fatigue, weight gain, and other symptoms.

What causes it?

This makes a difference in some cases to how it can be treated/managed. Causes include:

- Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune condition

- Severe inflammation (end result is similar to the above, but more treatable)

- Dietary deficiencies, especially iodine deficiency

- Secondary endocrine issues, e.g. pituitary gland didn’t make enough TSH for the thyroid gland to do its thing

- Some medications (ask your pharmacist)

We can’t do a lot about those last two by leveraging diet alone, but we can make a big difference to the others.

What to eat (and what to avoid)

There is nuance here, which we’ll go into a bit, but let’s start by giving the

one-linetwo-line summary that tends to be the dietary advice for most things:- Eat a nutrient-dense whole-foods diet (shocking, we know)

- Avoid sugar, alcohol, flour, processed foods (ditto)

What’s the deal with meat and dairy?

- Meat: avoid red and processed meats; poultry and fish are fine or even good (unless fried; don’t do that)

- Dairy: limit/avoid milk; but unsweetened yogurt and cheese are fine or even good

What’s the deal with plants?

First, get plenty of fiber, because that’s important to ease almost any inflammation-related condition, and for general good health for most people (an exception is if you have Crohn’s Disease, for example).

If you have Hashimoto’s, then gluten (as found in wheat, barley, and rye) may be an issue, but the jury is still out, science-wise. Here’s an example study for “avoid gluten” and “don’t worry about gluten”, respectively:

- The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Thyroid Autoimmunity in Women with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

- Doubtful Justification of the Gluten-Free Diet in the Course of Hashimoto’s Disease

So, you might want to skip it, to be on the safe side, but that’s up to you (and the advice of your nutritionist/doctor, as applicable).

A word on goitrogens…

Goitrogens are found in cruciferous vegetables and soy, both of which are very healthy foods for most people, but need some extra awareness in the case of hypothyroidism. This means there’s no need to abstain completely, but:

- Keep serving sizes small, for example a 100g serving only

- Cook goitrogenic foods before eating them, to greatly reduce goitrogenic activity

For more details, reading even just the abstract (intro summary) of this paper will help you get healthy cruciferous veg content without having a goitrogenic effect.

(as for soy, consider just skipping that if you suffer from hypothyroidism)

What nutrients to focus on getting?

- Top tier nutrients: iodine, selenium, zinc

- Also important: vitamin B12, vitamin D, magnesium, iron

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: