What is PNF stretching, and will it improve my flexibility?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Whether improving your flexibility was one of your new year’s resolutions, or you’ve been inspired watching certain tennis stars warming up at the Australian Open, maybe 2025 has you keen to focus on regular stretching.

However, a quick Google search might leave you overwhelmed by all the different stretching techniques. There’s static stretching and dynamic stretching, which can be regarded as the main types of stretching.

But there are also some other potentially lesser known types of stretching, such as PNF stretching. So if you’ve come across PNF stretching and it piques your interest, what do you need to know?

What is PNF stretching?

PNF stretching stands for proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. It was developed in the 1940s in the United States by neurologist Herman Kabat and physical therapists Margaret Knott and Dorothy Voss.

PNF stretching was initially designed to help patients with neurological conditions that affect the movement of muscles, such as polio and multiple sclerosis.

By the 1970s, its popularity had seen PNF stretching expand beyond the clinic and into the sporting arena where it was used by athletes and fitness enthusiasts during their warm-up and to improve their flexibility.

Although the specifics have evolved over time, PNF essentially combines static stretching (where a muscle is held in a lengthened position for a short period of time) with isometric muscle contractions (where the muscle produces force without changing length).

PNF stretching is typically performed with the help of a partner.

There are 2 main types

The two most common types of PNF stretching are the “contract-relax” and “contract-relax-agonist-contract” methods.

The contract-relax method involves putting a muscle into a stretched position, followed immediately by an isometric contraction of the same muscle. When the person stops contracting, the muscle is then moved into a deeper stretch before the process is repeated.

For example, to improve your hamstring flexibility, you could lie down and get a partner to lift your leg up just to the point where you begin to feel a stretch in the back of your thigh.

Once this sensation eases, attempt to push your leg back towards the ground as your partner resists the movement. After this, your partner should now be able to lift your leg up slightly higher than before until you feel the same stretching sensation.

This technique was based on the premise that the contracted muscle would fall “electrically silent” following the isometric contraction and therefore not offer its usual level of resistance to further stretching (called “autogenic inhibition”). The contract-relax method attempts to exploit this brief window to create a deeper stretch than would otherwise be possible without the prior muscle contraction.

The contract-relax-agonist-contract method is similar. But after the isometric contraction of the stretched muscle, you perform an additional contraction of the muscle group opposing the muscle being stretched (referred to as the “agonist” muscle), before the muscle is moved into a static stretch once more.

Again, if you’re trying to improve hamstring flexibility, immediately after trying to push your leg towards the ground you would attempt to lift it back towards the ceiling (this bit without partner resistance). You would do this by contracting the muscles on the front of the thigh (the quadriceps, the agonist muscle in this case).

Likewise, after this, your partner should be able to lift your leg up slightly higher than before.

The contract-relax-agonist-contract method is said to take advantage of a phenomenon known as “reciprocal inhibition.” This is where contracting the muscle group opposite that of the muscle being stretched leads to a short period of reduced activation of the stretched muscle, allowing the muscle to stretch further than normal.

What does the evidence say?

Research has shown PNF stretching is associated with improved flexibility.

While it has been suggested that both PNF methods improve flexibility via changes in nervous system function, research suggests they may simply improve our ability to tolerate stretching.

It’s worth noting most of the research on PNF stretching and flexibility has focused on healthy populations. This makes it difficult to provide evidence-based recommendations for people with clinical conditions.

And it may not be the most effective method if you’re looking to improve your flexibility in the long term. A 2018 review found static stretching was better for improving flexibility compared to PNF stretching. But other research has found it could offer greater immediate benefits for flexibility than static stretching.

At present, similar to other types of stretching, research linking PNF stretching to injury prevention and improved athletic performance is relatively inconclusive.

PNF stretching may actually lead to small temporary deficits in performance of strength, power, and speed-based activities if performed immediately beforehand. So it’s probably best done after exercise or as a part of a standalone flexibility session.

How much should you do?

It appears that a single contract-relax or contract-relax-agonist-contract repetition per muscle, performed twice per week, is enough to improve flexibility.

The contraction itself doesn’t need to be hard and forceful – only about 20% of your maximal effort should suffice. The contraction should be held for at least three seconds, while the static stretching component should be maintained until the stretching sensation eases.

So PNF stretching is potentially a more time-efficient way to improve flexibility, compared to, for example, static stretching. In a recent study we found four minutes of static stretching per muscle during a single session is optimal for an immediate improvement in flexibility.

Is PNF stretching the right choice for me?

Providing you have a partner who can help you, PNF stretching could be a good option. It might also provide a faster way to become more flexible for those who are time poor.

However, if you’re about to perform any activities that require strength, power, or speed, it may be wise to limit PNF stretching to afterwards to avoid any potential deficits in performance.

Lewis Ingram, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of South Australia and Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Voluntary assisted dying is different to suicide. But federal laws conflate them and restrict access to telehealth

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Voluntary assisted dying is now lawful in every Australian state and will soon begin in the Australian Capital Territory.

However, it’s illegal to discuss it via telehealth. That means people who live in rural and remote areas, or those who can’t physically go to see a doctor, may not be able to access the scheme.

A federal private members bill, introduced to parliament last week, aims to change this. So what’s proposed and why is it needed?

What’s wrong with the current laws?

Voluntary assisted dying doesn’t meet the definition of suicide under state laws.

But the Commonwealth Criminal Code prohibits the discussion or dissemination of suicide-related material electronically.

This opens doctors to the risk of criminal prosecution if they discuss voluntary assisted dying via telehealth.

Successive Commonwealth attorneys-general have failed to address the conflict between federal and state laws, despite persistent calls from state attorneys-general for necessary clarity.

This eventually led to voluntary assistant dying doctor Nicholas Carr calling on the Federal Court of Australia to resolve this conflict. Carr sought a declaration to exclude voluntary assisted dying from the definition of suicide under the Criminal Code.

In November, the court declared voluntary assisted dying was considered suicide for the purpose of the Criminal Code. This meant doctors across Australia were prohibited from using telehealth services for voluntary assisted dying consultations.

Last week, independent federal MP Kate Chaney introduced a private members bill to create an exemption for voluntary assisted dying by excluding it as suicide for the purpose of the Criminal Code. Here’s why it’s needed.

Not all patients can physically see a doctor

Defining voluntary assisted dying as suicide in the Criminal Code disproportionately impacts people living in regional and remote areas. People in the country rely on the use of “carriage services”, such as phone and video consultations, to avoid travelling long distances to consult their doctor.

Other people with terminal illnesses, whether in regional or urban areas, may be suffering intolerably and unable to physically attend appointments with doctors.

The prohibition against telehealth goes against the principles of voluntary assisted dying, which are to minimise suffering, maximise quality of life and promote autonomy.

Some people aren’t able to attend doctors’ appointments in person.

Jeffrey M Levine/ShutterstockDoctors don’t want to be involved in ‘suicide’

Equating voluntary assisted dying with suicide has a direct impact on doctors, who fear criminal prosecution due to the prohibition against using telehealth.

Some doctors may decide not to help patients who choose voluntary assisted dying, leaving patients in a state of limbo.

The number of doctors actively participating in voluntary assisted dying is already low. The majority of doctors are located in metropolitan areas or major regional centres, leaving some locations with very few doctors participating in voluntary assisted dying.

It misclassifies deaths

In state law, people dying under voluntary assisted dying have the cause of their death registered as “the disease, illness or medical condition that was the grounds for a person to access voluntary assisted dying”, while the manner of dying is recorded as voluntary assisted dying.

In contrast, only coroners in each state and territory can make a finding of suicide as a cause of death.

In 2017, voluntary assisted dying was defined in the Coroners Act 2008 (Vic) as not a reportable death, and thus not suicide.

The language of suicide is inappropriate for explaining how people make a decision to die with dignity under the lawful practice of voluntary assisted dying.

There is ongoing taboo and stigma attached to suicide. People who opt for and are lawfully eligible to access voluntary assisted dying should not be tainted with the taboo that currently surrounds suicide.

So what is the solution?

The only way to remedy this problem is for the federal government to create an exemption in the Criminal Code to allow telehealth appointments to discuss voluntary assisted dying.

Chaney’s private member’s bill is yet to be debated in federal parliament.

If it’s unsuccessful, the Commonwealth attorney-general should pass regulations to exempt voluntary assisted dying as suicide.

A cooperative approach to resolve this conflict of laws is necessary to ensure doctors don’t risk prosecution for assisting eligible people to access voluntary assisted dying, regional and remote patients have access to voluntary assisted dying, families don’t suffer consequences for the erroneous classification of voluntary assisted dying as suicide, and people accessing voluntary assisted dying are not shrouded with the taboo of suicide when accessing a lawful practice to die with dignity.

Failure to change this will cause unnecessary suffering for patients and doctors alike.

Michaela Estelle Okninski, Lecturer of Law, University of Adelaide; Marc Trabsky, Associate professor, La Trobe University, and Neera Bhatia, Associate Professor in Law, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Black Coffee vs Orange Juice – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing black coffee to orange juice, we picked the coffee.

Why?

While this one isn’t a very like-for-like choice, it’s a choice often made, so it bears examining.

In favor of the orange juice, it has vitamins A and C and the mineral potassium, while the coffee contains no vitamins or minerals beyond trace amounts.

However, to offset that: drinking juice is one of the worst ways to consume sugar; the fruit has not only been stripped of its fiber, but also is in its most readily absorbable state (liquid), meaning that this is going to cause a blood sugar spike, which if done often can lead to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and more. Now, the occasional glass of orange juice (and resultant blood sugar spike) isn’t going to cause disease by itself, but everything we consume tips the scales of our health towards wellness or illness (or sometimes both, in different ways), and in this case, juice has a rather major downside that ought not be ignored.

In favor of the coffee, it has a lot of beneficial phytochemicals (mostly antioxidant polyphenols of various kinds), with no drawbacks worth mentioning unless you have a pre-existing condition of some kind.

Coffee can of course be caffeinated or decaffeinated, and we didn’t specify which here. Caffeine has some pros and cons that at worst, balance each other out, and whether or not it’s caffeinated, there’s nothing in coffee to offset the beneficial qualities of the antioxidants we mentioned before.

Obviously, in either case we are assuming consuming in moderation.

In short:

- orange juice has negatives that at least equal, if not outweigh, its positives

- coffee‘s benefits outweigh any drawbacks for most people

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- The Bitter Truth About Coffee (or is it?)

- Caffeine: Cognitive Enhancer Or Brain-Wrecker?

- Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Mediterranean Diet… In A Pill?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Does It Come In A Pill?

For any as yet unfamiliar with the Mediterranean diet, you may be wondering what it involves, beyond a general expectation that it’s a diet popularly enjoyed in the Mediterranean. What image comes to mind?

We’re willing to bet that tomatoes feature (great source of lycopene, by the way, and if you’re not getting lycopene, you’re missing out), but what else?

- Salads, perhaps? Vegetables, olives? Olive oil, yea or nay?

- Bread? Pasta? Prosciutto, salami? Cheese?

- Pizza but only if it’s Romana style, not Chicago?

- Pan-seared liver, with some fava beans and a nice Chianti?

In fact, the Mediterranean diet is quite clear on all these questions, so to read about these and more (including a “this yes, that no” list), see:

What Is The Mediterranean Diet, And What Is It Good For?

So, how do we get that in a pill?

A plucky band of researchers, Dr. Chiara de Lucia et al. (quite a lot of “et al.”; nine listed authors on the study), wondered to what extent the benefits of the Mediterranean diet come from the fact that the Mediterranean diet is very rich in polyphenols, and set about testing that, by putting the same polyphenols in capsule form, and running a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical intervention trial.

Now, polyphenols are not the only reason the Mediterranean diet is great; there are also other considerations, such as:

- a great macronutrient balance with lots of fiber, healthy fats, moderate carbs, and protein from select sources

- the absence or at least very low presence of a lot of harmful substances such as refined seed oils, added sugars, refined carbohydrates, and the like (“but pasta” yes pasta; in moderation and wholegrain and served with extra sources of fiber and healthy fats, all of which slow down the absorption of the carbs)

…but polyphenols are admittedly very important too; we wrote about some common aspects of them here:

Tasty Polyphenols: Enjoy Bitter Foods For Your Heart & Brain

As for what Dr. de Lucia et al. put into the capsule, behold…

The ingredients:

- Apple Extract 10.0%

- Pomegranate Extract 10.0%

- Tomato Powder 2.5%

- Beet, Spray Dried 2.5%

- Olive Extract 7.5%

- Rosemary Extract 7.5%

- Green Coffee Bean Extract (CA) 7.5%

- Kale, Freeze Dried 2.5%

- Onion Extract 10.0%

- Ginger Extract 10.0%

- Grapefruit Extract 2.5%

- Carrot, Air Dried 2.5%

- Grape Skin Extract 17.5%

- Blueberry Extract 2.5%

- Currant, Freeze Dried 2.5%

- Elderberry, Freeze Dried 2.5%

And the relevant phytochemicals they contain:

- Quercetin

- Luteolin

- Catechins

- Punicalagins

- Phloretin

- Ellagic Acid

- Naringin

- Apigenin

- Isorhamnetin

- Chlorogenic Acids

- Rosmarinic Acid

- Anthocyanins

- Kaempferol

- Proanthocyanidins

- Myricetin

- Betanin

And what, you may wonder, did they find? Well, first let’s briefly summarise the setup of the study:

They took volunteers (n=30), average age 67, BMI >25, without serious health complaints, not taking other supplements, not vegetarian or vegan, not consuming >5 cups of coffee per day, and various other stipulations like that, to create a fairly homogenous study group who were expected to respond well to the intervention. In contrast, someone who takes antioxidant supplements, already eats many different color plants per day, and drinks 10 cups of coffee, probably already has a lot of antioxidant activity going on, and someone with a lower BMI will generally have lower resting levels of inflammatory markers, so it’s harder to see a change, proportionally.

About those inflammatory markers: that’s what they were testing, to see whether the intervention “worked”; essentially, did the levels of inflammatory markers go up or down (up is bad; down is good).

For more on inflammation, by the way, see:

How to Prevent (or Reduce) Inflammation

…which also explains what it actually is, and some important nuances about it.

Back to the study…

They gave half the participants the supplement for a week and the other half placebo; had a week’s gap as a “washout”, then repeated it, switching the groups, taking blood samples before and after each stage.

What they found:

The group taking the supplement had lower inflammatory markers after a week of taking it, while the group taking the placebo had relatively higher inflammatory markers after a week of taking it; this trend was preserved across both groups (i.e., when they switched roles for the second half).

The results were very significant (p=0.01 or thereabouts), and yet at the same time, quite modest (i.e. the supplement made a very reliable, very small difference), probably because of the small dose (150mg) and small intervention period (1 week).

What the researchers concluded from this

The researchers concluded that this was a success; the study had been primarily to provide proof of principle, not to rock the world. Now they want the experiment to be repeated with larger sample sizes, greater heterogeneity, larger doses, and longer intervention periods.

This is all very reasonable and good science.

What we conclude from this

That ingredients list makes for a good shopping list!

Well, not the extracts they listed, necessarily, but rather those actual fruits, vegetables, etc.

If nine top scientists (anti-aging specialists, neurobiologists, pharmacologists, and at least one professor of applied statistics) came to the conclusion that to get the absolute most bang-for-buck possible, those are the plants to get the phytochemicals from, then we’re not going to ignore that.

So, take another list above and ask yourself: how many of those 16 foods do you eat regularly, and could you work the others in?

Want to make your Mediterranean diet even better?

While the Mediterranean diet is a top-tier catch-all, it can be tweaked for specific areas of health, for example giving it an extra focus on heart health, or brain health, or being anti-inflammatory, or being especially gut healthy:

Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

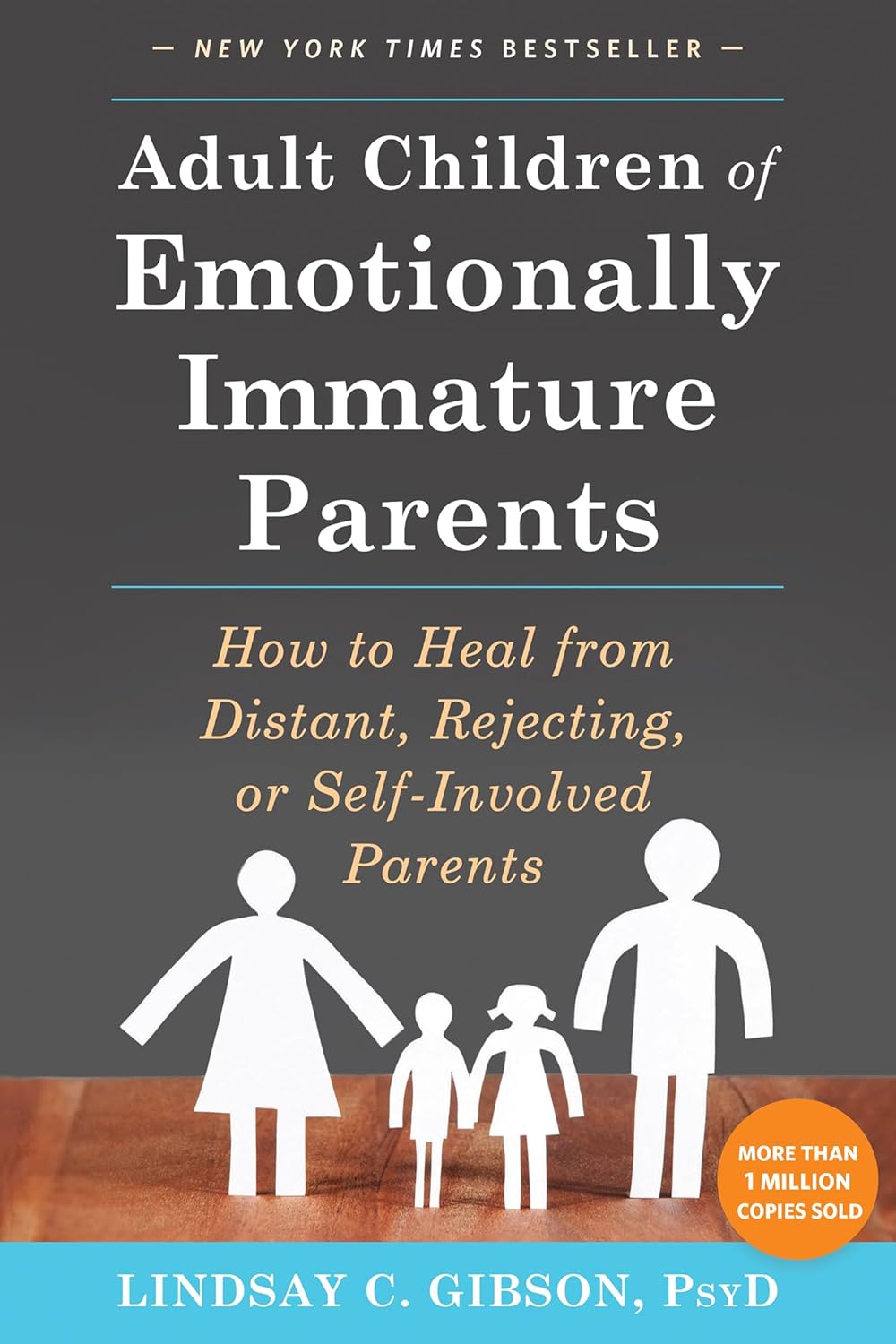

Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents – by Dr. Lindsay Gibson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Not everyone had the best of parents, and the harm done can last well beyond childhood. This book looks at healing that.

Dr. Gibson talks about four main kinds of “difficult” parents, though of course they can overlap:

- The emotional parent, with their unpredictable outbursts

- The driven parent, with their projected perfectionism

- The passive parent, with their disinterest and unreliability

- The rejecting parent, with their unavailability and insults

For all of them, it’s common that nothing we could do was ever good enough, and that leaves a deep scar. To add to it, the unfavorable dynamic often persists in adult life, assuming everyone involved is still alive and in contact.

So, what to do about it? Dr. Gibson advocates for first getting a good understanding of what wasn’t right/normal/healthy, because it’s easy for a lot of us to normalize the only thing we’ve ever known. Then, beyond merely noting that no child deserved that lack of compassion, moving on to pick up the broken pieces one by one, and address each in turn.

The style of the book is anecdote-heavy (case studies, either anonymized or synthesized per common patterns) in a way that will probably be all-too-relatable to a lot of readers (assuming that if you buy this book, it’s for a reason), science-moderate (references peppered into the text; three pages of bibliography), and practicality-dense—that is to say, there are lots of clear usable examples, there are self-assessment questionnaires, there are worksheets for now making progress forward, and so forth.

Bottom line: if one or more of the parent types above strikes a chord with you, there’s a good chance you could benefit from this book.

Click here to check out Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents, and rebuild yourself!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Can You Reverse Gray Hair? A Dermatologist Explains

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines states “any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no“—it’s not really a universal truth, but it’s true surprisingly often, and, as board certified dermatologist “The Beauty MD” Dr. Sam Ellis explains, it’s true in this case.

But, all is not lost.

Physiological Factors

Hair color is initially determined by genes and gene expression, instructing the body to color it with melanin (brown and black) and/or pheomelanin (blonde and red). If and when the body produces less of those pigments, our hair will go gray.

Factors that affect if/when our hair will go gray include:

- Genetics: primary determinant, essentially a programmed change

- Age: related to the above, but critically, the probability of going gray in any given year increases with age

- Ethnicity: the level of melanin in our skin is an indicator of how long we are likely to maintain melanin in our hair. Black people with the darkest skintones will thus generally go gray last, whereas white people with the lightest skintones will generally go gray first, and so on for a spectrum between the two.

- Medical conditions: immune conditions such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, and pernicious anemia promote an earlier loss of pigmentation

- Stress: oxidative stress, mainly, so factors like smoking will cause earlier graying. But yes, also chronic emotional stress does lead to oxidative stress too. Interestingly, this seems to be more about norepinephrine than cortisol, though.

- Nutrient deficiencies: the body can make a lot of things, but it needs the raw ingredients. Not having the right amounts of important vitamins and minerals will result in a loss of pigmentation (amongst other more serious problems). Vitamins B6, B9, and B12 are talked about in the video, as are iron and zinc. Copper is also needed for some hair colors. Selenium is needed for good hair health in general (but not too much, as an excess of selenium paradoxically causes hair loss), and many related things will stop working properly without adequate magnesium. Hair health will also benefit a lot from plenty of vitamin B7.

So, managing the above factors (where possible; obviously some of the above aren’t things we can influence) will result in maintaining one’s hair pigment for longer. As for texture, by the way, the reason gray hair tends to have a rougher texture is not for the lack of pigment itself, but is due to decreased sebum production. Judicious use of exogenous hair oils (e.g. argan oil, coconut oil, or whatever your preference may be) is a fine way to keep your grays conditioned.

However, once your hair has gone gray, there is no definitive treatment with good evidence for reversing that, at present. Dye it if you want to, or don’t. Many people (including this writer, who has just a couple of streaks of gray herself) find gray hair gives a distinguished look, and such harmless signs of age are a privilege not everyone gets to reach, and thus may be reasonably considered a cause for celebration

For more on all of the above, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Is Chiropractic All It’s Cracked Up To Be?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Is Chiropractic All It’s Cracked Up To Be?

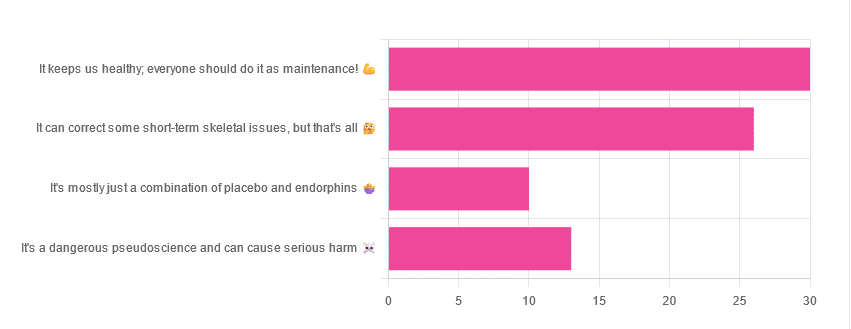

Yesterday, we asked you for your opinions on chiropractic medicine, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of results:

- 38% of respondents said it keeps us healthy, and everyone should do it as maintenance

- 33% of respondents said it can correct some short-term skeletal issues, but that’s all

- 16% of respondents said that it’s a dangerous pseudoscience and can cause serious harm

- 13% of respondents said that it’s mostly just a combination of placebo and endorphins

Respondents also shared personal horror stories of harm done, personal success stories of things cured, and personal “it didn’t seem to do anything for me” stories.

What does the science say?

It’s a dangerous pseudoscience and can cause harm: True or False?

False and True, respectively.

That is to say, chiropractic in its simplest form that makes the fewest claims, is not a pseudoscience. If somebody physically moves your bones around, your bones will be physically moved. If your bones were indeed misaligned, and the chiropractor is knowledgeable and competent, this will be for the better.

However, like any form of medicine, it can also cause harm; in chiropractic’s case, because it more often than not involves manipulation of the spine, this can be very serious:

❝Twenty six fatalities were published in the medical literature and many more might have remained unpublished.

The reported pathology usually was a vascular accident involving the dissection of a vertebral artery.

Conclusion: Numerous deaths have occurred after chiropractic manipulations. The risks of this treatment by far outweigh its benefit.❞

Source: Deaths after chiropractic: a review of published cases

From this, we might note two things:

- The abstract doesn’t note the initial sample size; we would rather have seen this information expressed as a percentage. Unfortunately, the full paper is not accessible, and nor are many of the papers it cites.

- Having a vertebral artery fatally dissected is nevertheless not an inviting prospect, and is certainly a very reasonable cause for concern.

It’s mostly just a combination of placebo and endorphins: True or False?

True or False, depending on what you went in for:

- If you went in for a regular maintenance clunk-and-click, then yes, you will get your clunk-and-click and feel better for it because you had a ritualized* experience and endorphins were released.

- If you went in for something that was actually wrong with your skeletal alignment, to get it corrected, and this correction was within your chiropractor’s competence, then yes, you will feel better because a genuine fault was corrected.

*this is not implying any mysticism, by the way. Rather it means simply that placebo effect is strongest when there is a ritual associated with it. In this case it means going to the place, sitting in a pleasant waiting room, being called in, removing your shoes and perhaps some other clothes, getting the full attention of a confident and assured person for a while, this sort of thing.

With regard to its use to combat specifically spinal pain (i.e., perhaps the most obvious thing to treat by chiropractic spinal manipulation), evidence is slightly in favor, but remains unclear:

❝Due to the low quality of evidence, the efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulation compared with a placebo or no treatment remains uncertain. ❞

Source: Clinical Effectiveness and Efficacy of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation for Spine Pain

It can correct some short-term skeletal issues, but that’s all: True or False?

Probably True.

Why “probably”? The effectiveness of chiropractic treatment for things other than short-term skeletal issues has barely been studied. From this, we may wish to keep an open mind, while also noting that it can hardly claim to be evidence-based—and it’s had hundreds of years to accumulate evidence. In all likelihood, publication bias has meant that studies that were conducted and found inconclusive or negative results were simply not published—but that’s just a hypothesis on our part.

In the case of using chiropractic to treat migraines, a very-related-but-not-skeletal issue, researchers found:

❝Pre-specified feasibility criteria were not met, but deficits were remediable. Preliminary data support a definitive trial of MCC+ for migraine.❞

Translating this: “it didn’t score as well as we hoped, but we can do better. We got some positive results, and would like to do another, bigger, better trial; please fund it”

Source: Multimodal chiropractic care for migraine: A pilot randomized controlled trial

Meanwhile, chiropractors’ claims for very unrelated things have been harshly criticized by the scientific community, for example:

Misinformation, chiropractic, and the COVID-19 pandemic

About that “short-term” aspect, one of our subscribers put it quite succinctly:

❝Often a skeletal correction is required for initial alignment but the surrounding fascia and muscles also need to be treated to mobilize the joint and release deep tissue damage surrounding the area. In combination with other therapies chiropractic support is beneficial.❞

This is, by the way, very consistent with what was said in the very clinically-dense book we reviewed yesterday, which has a chapter on the short-term benefits and limitations of chiropractic.

A truism that holds for many musculoskeletal healthcare matters, holds true here too:

❝In a battle between muscle and bone, muscle will always win❞

In other words…

Chiropractic can definitely help put misaligned bones back where they should be. However, once they’re there, if the cause of their misalignment is not treated, they will just re-misalign themselves shortly after you walking out of your session.

This is great for chiropractors, if it keeps you coming back for endless appointments, but it does little for your body beyond give you a brief respite.

So, by all means go to a chiropractor if you feel so inclined (and you do not fear accidental arterial dissection etc), but please also consider going to a physiotherapist, and potentially other medical professions depending on what seems to be wrong, to see about addressing the underlying cause.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: