The Osteoporosis Breakthrough – by Dr. Doug Lucas

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Osteoporosis” and “break” often don’t go well together, but here they do. So, what’s the breakthrough here?

There isn’t one, honestly. But if we overlook the marketing choices and focus on the book itself, the content here is genuinely good:

The book offers a comprehensive multivector approach to combatting osteoporosis, e.g:

- Diet

- Exercise

- Other lifestyle considerations

- Supplements

- Hormones

- Drugs

The author considers drugs a good and important tool for some people with osteoporosis, but not most. The majority of people, he considers, will do better without drugs—by tackling things more holistically.

The advice here is sound and covers all reasonable angles without getting hung up on the idea of there being a single magical solution for all.

Bottom line: if you’re looking for a book that’s a one-stop-shop for strategies against osteoporosis, this is a good option.

Click here to check out The Osteoporosis Breakthrough, and keep your bones strong!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Turns out the viral ‘Sleepy Girl Mocktail’ is backed by science. Should you try it?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many of us wish we could get a better night’s sleep. Wouldn’t it be great if it was as easy as a mocktail before bed?

That’s what the latest viral trend might have us believe. The “Sleepy Girl Mocktail” is a mix of tart cherry juice, powdered magnesium supplement and soda water. TikTok videos featuring the concoction have garnered hundreds of thousands of views. But, what does the science say? Do these ingredients actually help us sleep?

Tart cherry juice

There is research to show including tart cherry juice in your diet improves overall sleep. Clinical trials show tart cherry juice increases sleep quality and quantity, as well as a lessening insomnia symptoms (compared to a placebo). This could be due to the presence of melatonin, a sleep-promoting hormone, in cherries.

Tart cherry varieties such as Jerte Valley or Montmorency have the highest concentration of melatonin (approximately 0.135 micrograms of melatonin per 100g of cherry juice). Over the counter melatonin supplements can range from 0.5 milligram to over 100 milligrams, with research suggesting those beginning to take melatonin start with a dose of 0.5–2 milligrams to see an improvement in sleep.

Melatonin naturally occurs in our bodies. Our body clock promotes the release of melatonin in the evening to help us sleep, specifically in the two hours before our natural bedtime.

If we want to increase our melatonin intake with external sources, such as cherries, then we should be timing our intake with our natural increase in melatonin. Supplementing melatonin too close to bed will mean we may not get the sleep-promoting benefits in time to get off to sleep easily. Taking melatonin too late may even harm our long-term sleep health by sending the message to our body clock to delay the release of melatonin until later in the evening.

Magnesium – but how much?

Magnesium also works to promote melatonin, and magnesium supplements have been shown to improve sleep outcomes.

However, results vary depending on the amount of magnesium people take. And we don’t yet have the answers on the best dose of magnesium for sleep benefits.

We do know magnesium plays a vital role in energy production and bone development, making it an important daily nutrient for our diets. Foods rich in magnesium include wheat cereal or bread, almonds, cashews, pumpkin seeds, spinach, artichokes, green beans, soy milk and dark chocolate.

Bubbly water

Soda water serves as the base of the drink, rather than a pathway to better sleep. And bubbly water may make the mix more palatable. It is important to keep in mind that drinking fluids close to bedtime can be disruptive to our sleep as it might lead to waking during the night to urinate.

Healthy sleep recommendations include avoiding water intake in the two hours before bed. Having carbonated beverages too close to bed can also trigger digestive symptoms such as bloating, gassiness and reflux during the night.

Bottoms up?

Overall, there is evidence to support trying out the Sleepy Girl Mocktail to see if it improves sleep, however there are some key things to remember:

timing: to get the benefits of this drink, avoid having it too close to bed. Aim to have it two hours before your usual bedtime and avoid fluids after this time

consistency: no drink is going to be an immediate cure for poor sleep. However, this recipe could help promote sleep if used strategically (at the right time) and consistently as part of a balanced diet. It may also introduce a calming evening routine that helps your brain relax and signals it’s time for bed

- maximum magnesium: be mindful of the amount of magnesium you are consuming. While there are many health benefits to magnesium, the recommended daily maximum amounts are 420mg for adult males and 320mg for adult females. Exceeding the maximum can lead to low blood pressure, respiratory distress, stomach problems, muscle weakness and mood problems

sugar: in some of the TikTok recipes sugar (as flavoured sodas, syrups or lollies) is added to the drink. While this may help hide the taste of the tart cherry juice, the consumption of sugar too close to bed may make it more difficult to get to sleep. And sugar in the evening raises blood sugar levels at a time when our body is not primed to be processing sugar. Long term, this can increase our risk of diabetes

sleep environment: follow good sleep hygiene practices including keeping a consistent bedtime and wake time, a wind-down routine before bed, avoiding electronic device use like phones or laptops in bed, and avoiding bright light in the evening. Bright light works to suppress our melatonin levels in the evening and make us more alert.

What about other drinks?

Other common evening beverages include herbal tisanes or teas, hot chocolate, or warm milk.

Milk can be especially beneficial for sleep, as it contains the amino acid tryptophan, which can promote melatonin production. Again, it is important to also consider the timing of these drinks and to avoid any caffeine in tea and too much chocolate too close to bedtime, as this can make us more alert rather than sleepy.

Getting enough sleep is crucial to our health and wellbeing. If you have tried multiple strategies to improve your sleep and things are not getting better, it may be time to seek professional advice, such as from a GP.

Charlotte Gupta, Postdoctoral research fellow, CQUniversity Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Healthiest-Three-Nut Butter

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’re often telling you to “diversify your nuts”, so here’s a great way to get in three at once with no added sugar, palm oil, or preservatives, and only the salt you choose to put in. We’ve picked three of the healthiest nuts around, but if you happen to be allergic, don’t worry, we’ve got you covered too.

You will need

- 1 cup almonds (if allergic, substitute a seed, e.g. chia, and make it ½ cup)

- 1 cup walnuts (if allergic, substitute a seed, e.g. pumpkin, and make it ½ cup)

- 1 cup pistachios (if allergic, substitute a seed, e.g. poppy, and make it ½ cup)

- 1 tbsp almond oil (if allergic, substitute extra virgin olive oil) (if you prefer sweet nut butter, substitute 1 tbsp maple syrup; the role here is to emulsify the nuts, and this will do the same job)

- Optional: ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1a) If using nuts, heat your oven to 350℉ / 180℃. Place the nuts on a baking tray lined with baking paper, and bake/roast for about 10 minutes, but keep an eye on it to ensure the nuts don’t burn, and jiggle them if necessary to ensure they toast evenly. Once done, allow to cool.

1b) If using seeds, you can either omit that step, or do the same for 5 minutes if you want to, but really it’s not necessary.

2) Blend all ingredients (nuts/seeds, oil, MSG/salt) in a high-speed blender. Note: this will take about 10 minutes in total, and we recommend you do it in 30-second bursts so as to not overheat the motor. You also may need to periodically scrape the mixture down the side of the blender, to ensure a smooth consistency.

3) Transfer to a clean jar, and enjoy at your leisure:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Sesame Seeds vs Poppy Seeds – Which is Healthier?

- If You’re Not Taking Chia, You’re Missing Out

- Sea Salt vs MSG – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

What You Should Have Been Told About The Menopause Beforehand

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What You Should Have Been Told About Menopause Beforehand

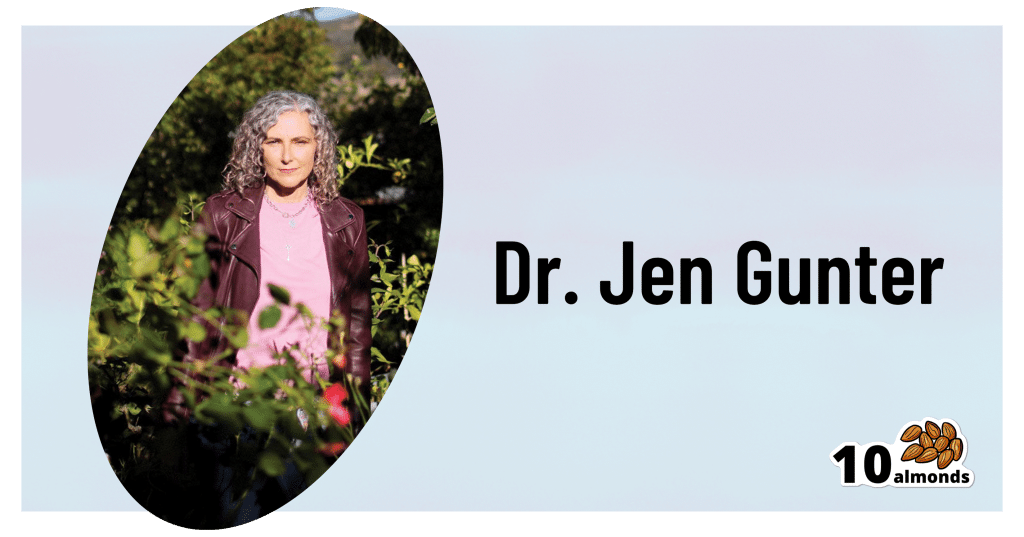

This is Dr. Jen Gunter. She’s a gynecologist, specializing in chronic pain and vulvovaginal disorders. She’s also a woman on a mission to demystify things that popular culture, especially in the US, would rather not talk about.

When was the last time you remember the menopause being referenced in a movie or TV show? If you can think of one at all, was it just played for laughs?

And of course, the human body can be funny, so that’s not necessarily the problem, but it sure would be nice if that weren’t all that there is!

So, what does Dr. Gunter want us to know?

It’s a time of changes, not an end

The name “menopause” is misleading. It’s not a “pause”, and those menses aren’t coming back.

And yet, to call it a “menostop” would be differently misleading, because there’s a lot more going on than a simple cessation of menstruation.

Estrogen levels will drop a lot, testosterone levels may rise slightly, mood and sleep and appetite and sex drive will probably be affected (progesterone can improve all these things!) and

not to mention butwe’re going to mention: vaginal atrophy, which is very normal and very treatable with a topical estrogen cream. Untreated menopause can also bring a whole lot of increased health risks (for example, heart disease, osteoporosis, and, counterintuitively given the lower estrogen levels, breast cancer).However, with a little awareness and appropriate management, all these things can usually be navigated with minimal adverse health outcomes.

Dr Gunter, for this reason, refers to it interchangeably as “the menopausal transition”. She describes it as being less like a cliff edge we fall off, and more like a bridge we cross.

Bridges can be dangerous to cross! But they can also get us safely where we’re going.

Ok, so how do we manage those things?

Dr. Gunter is a big fan of evidence-based medicine, so we’ll not be seeing any yonic crystals or jade eggs. Or “goop”.

See also: Meet Goop’s Number One Enemy

For most people, she recommends Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT), which falls under the more general category of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT).

This is the most well-evidenced, science-based way to avoid most of the risks associated with menopause.

Nevertheless, there are scare-stories out there, ranging from painful recommencement of bleeding, to (once again) increased risk of breast cancer. However, most of these are either misunderstandings, or unrelated to menopause and MHT, and are rather signs of other problems that should not be ignored.

To get a good grounding in this, you might want to read her Hormone Therapy Guide, freely available as a standalone section on her website. This series of posts is dedicated to hormone therapy. It starts with some basics and builds on that knowledge with each post:

Dr. Gunter’s Guide To The Hormone Menoverse

What about natural therapies?

There are some non-hormonal things that work, but these are mostly things that:

- give a statistically significant reduction in symptoms

- give the same statistically significant reduction in symptoms as placebo

As Dr. Gunter puts it:

❝While most of the studies of prescription medications for hot flashes have an appropriate placebo arm, this is rarely the case with so-called alternative therapies.

In fact, the studies here are almost always low quality, so it’s often not possible to conclude much.

Many reviews that look at these studies often end with a line that goes something like, “Randomized trials with a placebo arm, a low risk of bias, and adequate sample sizes are urgently needed.”

You should interpret this kind of conclusion as the polite way of saying, “We need studies that aren’t BS to say something constructive.”❞

However, if it works, it works, whatever its mechanism. It’s just good, when making medical decisions, to do so with the full facts!

For that matter, even Dr. Gunter acknowledges that while MHT can be lifechanging (in a positive way) for many, it’s not for everyone:

Informed Decisions: When Menopause Hormone Therapy Isn’t Recommended

Want to know more?

Dr. Gunter also has an assortment of books available, including The Menopause Manifesto (which we’ve reviewed previously), and some others that we haven’t, such as “Blood” and “The Vagina Bible”.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Terminal lucidity: why do loved ones with dementia sometimes ‘come back’ before death?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dementia is often described as “the long goodbye”. Although the person is still alive, dementia slowly and irreversibly chips away at their memories and the qualities that make someone “them”.

Dementia eventually takes away the person’s ability to communicate, eat and drink on their own, understand where they are, and recognise family members.

Since as early as the 19th century, stories from loved ones, caregivers and health-care workers have described some people with dementia suddenly becoming lucid. They have described the person engaging in meaningful conversation, sharing memories that were assumed to have been lost, making jokes, and even requesting meals.

It is estimated 43% of people who experience this brief lucidity die within 24 hours, and 84% within a week.

Why does this happen?

Terminal lucidity or paradoxical lucidity?

In 2009, researchers Michael Nahm and Bruce Greyson coined the term “terminal lucidity”, since these lucid episodes often occurred shortly before death.

But not all lucid episodes indicate death is imminent. One study found many people with advanced dementia will show brief glimmers of their old selves more than six months before death.

Lucidity has also been reported in other conditions that affect the brain or thinking skills, such as meningitis, schizophrenia, and in people with brain tumours or who have sustained a brain injury.

Moments of lucidity that do not necessarily indicate death are sometimes called paradoxical lucidity. It is considered paradoxical as it defies the expected course of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia.

But it’s important to note these episodes of lucidity are temporary and sadly do not represent a reversal of neurodegenerative disease.

Sadly, these episodes of lucidity are only temporary. Pexels/Kampus Production Why does terminal lucidity happen?

Scientists have struggled to explain why terminal lucidity happens. Some episodes of lucidity have been reported to occur in the presence of loved ones. Others have reported that music can sometimes improve lucidity. But many episodes of lucidity do not have a distinct trigger.

A research team from New York University speculated that changes in brain activity before death may cause terminal lucidity. But this doesn’t fully explain why people suddenly recover abilities that were assumed to be lost.

Paradoxical and terminal lucidity are also very difficult to study. Not everyone with advanced dementia will experience episodes of lucidity before death. Lucid episodes are also unpredictable and typically occur without a particular trigger.

And as terminal lucidity can be a joyous time for those who witness the episode, it would be unethical for scientists to use that time to conduct their research. At the time of death, it’s also difficult for scientists to interview caregivers about any lucid moments that may have occurred.

Explanations for terminal lucidity extend beyond science. These moments of mental clarity may be a way for the dying person to say final goodbyes, gain closure before death, and reconnect with family and friends. Some believe episodes of terminal lucidity are representative of the person connecting with an afterlife.

Why is it important to know about terminal lucidity?

People can have a variety of reactions to seeing terminal lucidity in a person with advanced dementia. While some will experience it as being peaceful and bittersweet, others may find it deeply confusing and upsetting. There may also be an urge to modify care plans and request lifesaving measures for the dying person.

Being aware of terminal lucidity can help loved ones understand it is part of the dying process, acknowledge the person with dementia will not recover, and allow them to make the most of the time they have with the lucid person.

For those who witness it, terminal lucidity can be a final, precious opportunity to reconnect with the person that existed before dementia took hold and the “long goodbye” began.

Yen Ying Lim, Associate Professor, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, Monash University and Diny Thomson, PhD (Clinical Neuropsychology) Candidate and Provisional Psychologist, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Scattered Minds – by Dr. Gabor Maté

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This was not the first book that Dr. Maté sat down to write, by far. But it was the first that he actually completed. Guess why.

Writing from a position of both personal and professional experience and understanding, Dr. Maté explores the inaptly-named Attention Deficit Disorder (if anything, there’s often a surplus of attention, just, to anything and everything rather than necessarily what would be most productive in the moment), its etiology, its presentation, and its management.

This is a more enjoyable book than some others by the same author, as while this condition certainly isn’t without its share of woes (often, for example, a cycle of frustration and shame re “why can’t I just do the things; this is ruining my life and it would be so easy if I could just do the things!”), it’s not nearly so bleak as entire books about trauma, addiction, and so forth (worthy as those books also are).

Dr. Maté frames it specifically as a development disorder, and one whereby with work, we can do the development later that (story of an ADHDer’s life) we should have done earlier but didn’t. In terms of practical advice, he includes a program for effecting this change, including as an adult.

The style is easy-reading, in small chapters, with ADHD’d-up readers in mind, giving a strong sense of speeding pleasantly through the book.

Bottom line: when it’s a book by Dr. Gabor Maté, you know it’s going to be good, and this is no exception. Certainly read it if you, anyone you care about, or even anyone you just spend a lot of time around, has ADHD or similar.

Click here to check out Scattered Minds, and unscatter yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Growing Inequality in Life Expectancy Among Americans

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The life expectancy among Native Americans in the western United States has dropped below 64 years, close to life expectancies in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Haiti. For many Asian Americans, it’s around 84 — on par with life expectancies in Japan and Switzerland.

Americans’ health has long been unequal, but a new study shows that the disparity between the life expectancies of different populations has nearly doubled since 2000. “This is like comparing very different countries,” said Tom Bollyky, director of the global health program at the Council on Foreign Relations and an author of the study.

Called “Ten Americas,” the analysis published late last year in The Lancet found that “one’s life expectancy varies dramatically depending on where one lives, the economic conditions in that location, and one’s racial and ethnic identity.” The worsening health of specific populations is a key reason the country’s overall life expectancy — at 75 years for men and 80 for women — is the shortest among wealthy nations.

To deliver on pledges from the new Trump administration to make America healthy again, policymakers will need to fix problems undermining life expectancy across all populations.

“As long as we have these really severe disparities, we’re going to have this very low life expectancy,” said Kathleen Harris, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina. “It should not be that way for a country as rich as the U.S.”

Since 2000, the average life expectancy of many American Indians and Alaska Natives has been steadily shrinking. The same has been true since 2014 for Black people in low-income counties in the southeastern U.S.

“Some groups in the United States are facing a health crisis,” Bollyky said, “and we need to respond to that because it’s worsening.”

Heart disease, car fatalities, diabetes, covid-19, and other common causes of death are directly to blame. But research shows that the conditions of people’s lives, their behaviors, and their environments heavily influence why some populations are at higher risk than others.

Native Americans in the West — defined in the “Ten Americas” study as more than a dozen states excluding California, Washington, and Oregon — were among the poorest in the analysis, living in counties where a person’s annual income averages below about $20,000. Economists have shown that people with low incomes generally live shorter lives.

Studies have also linked the stress of poverty, trauma, and discrimination to detrimental coping behaviors like smoking and substance use disorders. And reservations often lack grocery stores and clean, piped water, which makes it hard to buy and cook healthy food.

About 1 in 5 Native Americans in the Southwest don’t have health insurance, according to a KFF report. Although the Indian Health Service provides coverage, the report says the program is weak due to chronic underfunding. This means people may delay or skip treatments for chronic illnesses. Postponed medical care contributed to the outsize toll of covid among Native Americans: About 1 of every 188 Navajo people died of the disease at the peak of the pandemic.

“The combination of limited access to health care and higher health risks has been devastating,” Bollyky said.

At the other end of the spectrum, the study’s category of Asian Americans maintained the longest life expectancies since 2000. As of 2021, it was 84 years.

Education may partly underlie the reasons certain groups live longer. “People with more education are more likely to seek out and adhere to health advice,” said Ali Mokdad, an epidemiologist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, and an author of the paper. Education also offers more opportunities for full-time jobs with health benefits. “Money allows you to take steps to take care of yourself,” Mokdad said.

The group with the highest incomes in most years of the analysis was predominantly composed of white people, followed by the mainly Asian group. The latter, however, maintained the highest rates of college graduation, by far. About half finished college, compared with fewer than a third of other populations.

The study suggests that education partly accounts for differences among white people living in low-income counties, where the individual income averaged less than $32,363. Since 2000, white people in low-income counties in southeastern states — defined as those in Appalachia and the Lower Mississippi Valley — had far lower life expectancies than those in upper midwestern states including Montana, Nebraska, and Iowa. (The authors provide details on how the groups were defined and delineated in their report.)

Opioid use and HIV rates didn’t account for the disparity between these white, low-income groups, Bollyky said. But since 2010, more than 90% of white people in the northern group were high school graduates, compared with around 80% in the southeastern U.S.

The education effect didn’t hold true for Latino groups compared with others. Latinos saw lower rates of high school graduation than white people but lived longer on average. This long-standing trend recently changed among Latinos in the Southwest because of covid. Hispanic or Latino and Black people were nearly twice as likely to die from the disease.

On average, Black people in the U.S. have long experienced worse health than other races and ethnicities in the United States, except for Native Americans. But this analysis reveals a steady improvement in Black people’s life expectancy from 2000 to about 2012. During this period, the gap between Black and white life expectancies shrank.

This is true for all three groups of Black people in the analysis: Those in low-income counties in southeastern states like Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama; those in highly segregated and metropolitan counties, such as Queens, New York, and Wayne, Michigan, where many neighborhoods are almost entirely Black or entirely white; and Black people everywhere else.

Better drugs to treat high blood pressure and HIV help account for the improvements for many Americans between 2000 to 2010. And Black people, in particular, saw steep rises in high school graduation and gains in college education in that period.

However, progress stagnated for Black populations by 2016. Disparities in wealth grew. By 2021, Asian and many white Americans had the highest incomes in the study, living in counties with per capita incomes around $50,000. All three groups of Black people in the analysis remained below $30,000.

A wealth gap between Black and white people has historical roots, stretching back to the days of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and policies that prevented Black people from owning property in neighborhoods that are better served by public schools and other services. For Native Americans, a historical wealth gap can be traced to a near annihilation of the population and mass displacement in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Inequality has continued to rise for several reasons, such as a widening pay gap between predominantly white corporate leaders and low-wage workers, who are disproportionately people of color. And reporting from KFF Health News shows that decisions not to expand Medicaid have jeopardized the health of hundreds of thousands of people living in poverty.

Researchers have studied the potential health benefits of reparation payments to address historical injustices that led to racial wealth gaps. One new study estimates that such payments could reduce premature death among Black Americans by 29%.

Less controversial are interventions tailored to communities. Obesity often begins in childhood, for example, so policymakers could invest in after-school programs that give children a place to socialize, be active, and eat healthy food, Harris said. Such programs would need to be free for children whose parents can’t afford them and provide transportation.

But without policy changes that boost low wages, decrease medical costs, put safe housing and strong public education within reach, and ensure access to reproductive health care including abortion, Harris said, the country’s overall life expectancy may grow worse.

“If the federal government is really interested in America’s health,” she said, “they could grade states on their health metrics and give them incentives to improve.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: