The Immunostimulant Superfood –

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this book is not: a “detox cleanse” book of the kind that claims you can flush out the autism if you just eat enough celery.

What it rather is: an overview brain chemistry, gut microbiota, and the very many other bodily systems that interact with these “two brains”.

She also does some mythbusting of popular misconceptions (for example with regard to tryptophan), and explains with good science just what exactly such substances as gluten and casein can and can’t do.

The format is less of a textbook and more a multipart (i.e., chapter-by-chapter) lecture, in pop-science style though, making it very readable. There are a lot of practical advices too, and options to look up foods by effect, and what to eat for/against assorted mental states.

Bottom line: anyone who eats food is, effectively, drugging themselves in one fashion or another—so you might as well make a conscious choice about how to do so.

Click here to check out This Is Your Brain On Food, and choose what kind of day you have!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Healthy Hormones And How To Hack Them

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Healthy Hormones And How To Hack Them!

Hormones are vital for far more than they tend to get credit for. Even the hormones that people think of first—testosterone and estrogen—do a lot more than just build/maintain sexual characteristics and sexual function. Without them, we’d lack energy, we’d be depressed, and we’d soon miss the general smooth-running of our bodies that we take for granted.

And that’s without getting to the many less-talked-about hormones that play a secondary sexual role or are in the same general system…

How are your prolactin levels, for example?

Unless you’re ill, taking certain medications, recently gave birth, or picked a really interesting time to read this newsletter, they’re probably normal, by the way.

But, prolactin can explain “la petite mort”, the downturn in energy and the somewhat depressed mood that many men experience after orgasm.

Otherwise, if you have too much prolactin in general, you will be sleepy and depressed.

Prolactin’s primary role? In women, it stimulates milk production when needed. In men, it plays a role in regulating mood and metabolism.

Share This Post

-

Body on Fire – by Dr. Monica Aggarwal and Dr. Jyothi Rao

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are times when you do really need a doctor, not a dietician. But there are also times when a doctor will prescribe something for the symptom, leaving the underlying issue untouched. If only there were a way to have the best of both worlds!

That’s where Drs. Rao and Aggarwal come in. They’re both medical doctors… with a keen interest in nutrition and healthy lifestyle changes to make us less sick such that we have less need to go to the doctor at all.

Best of all, they understand—while some things are true for everyone—there’s not a one-size-fits all diet or exercise regime or even sleep setup.

So instead, they take us hand-in-hand (chapter by chapter!) through the various parts of our life (including our diet) that might need tweaking. Each of these changes, if taken up, promise a net improvement that becomes synergistic with the other changes. There’s a degree of biofeedback involved, and listening to your body, to be sure of what’s really best for you, not what merely should be best for you on paper.

The writing style is accessible while science-heavy. They don’t assume prior knowledge, and/but they sure deliver a lot. The book is more text than images, but there are plenty of medical diagrams, explanations, charts, and the like. You will feed like a medical student! And it’s very much worth studying.

Bottom line: highly recommendable even if you don’t have inflammation issues, and worth its weight in gold if you do.

Share This Post

-

Overdosing on Chemo: A Common Gene Test Could Save Hundreds of Lives Each Year

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One January morning in 2021, Carol Rosen took a standard treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Three gruesome weeks later, she died in excruciating pain from the very drug meant to prolong her life.

Rosen, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher, passed her final days in anguish, enduring severe diarrhea and nausea and terrible sores in her mouth that kept her from eating, drinking, and, eventually, speaking. Skin peeled off her body. Her kidneys and liver failed. “Your body burns from the inside out,” said Rosen’s daughter, Lindsay Murray, of Andover, Massachusetts.

Rosen was one of more than 275,000 cancer patients in the United States who are infused each year with fluorouracil, known as 5-FU, or, as in Rosen’s case, take a nearly identical drug in pill form called capecitabine. These common types of chemotherapy are no picnic for anyone, but for patients who are deficient in an enzyme that metabolizes the drugs, they can be torturous or deadly.

Those patients essentially overdose because the drugs stay in the body for hours rather than being quickly metabolized and excreted. The drugs kill an estimated 1 in 1,000 patients who take them — hundreds each year — and severely sicken or hospitalize 1 in 50. Doctors can test for the deficiency and get results within a week — and then either switch drugs or lower the dosage if patients have a genetic variant that carries risk.

Yet a recent survey found that only 3% of U.S. oncologists routinely order the tests before dosing patients with 5-FU or capecitabine. That’s because the most widely followed U.S. cancer treatment guidelines — issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network — don’t recommend preemptive testing.

The FDA added new warnings about the lethal risks of 5-FU to the drug’s label on March 21 following queries from KFF Health News about its policy. However, it did not require doctors to administer the test before prescribing the chemotherapy.

The agency, whose plan to expand its oversight of laboratory testing was the subject of a House hearing, also March 21, has said it could not endorse the 5-FU toxicity tests because it’s never reviewed them.

But the FDA at present does not review most diagnostic tests, said Daniel Hertz, an associate professor at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy. For years, with other doctors and pharmacists, he has petitioned the FDA to put a black box warning on the drug’s label urging prescribers to test for the deficiency.

“FDA has responsibility to assure that drugs are used safely and effectively,” he said. The failure to warn, he said, “is an abdication of their responsibility.”

The update is “a small step in the right direction, but not the sea change we need,” he said.

Europe Ahead on Safety

British and European Union drug authorities have recommended the testing since 2020. A small but growing number of U.S. hospital systems, professional groups, and health advocates, including the American Cancer Society, also endorse routine testing. Most U.S. insurers, private and public, will cover the tests, which Medicare reimburses for $175, although tests may cost more depending on how many variants they screen for.

In its latest guidelines on colon cancer, the Cancer Network panel noted that not everyone with a risky gene variant gets sick from the drug, and that lower dosing for patients carrying such a variant could rob them of a cure or remission. Many doctors on the panel, including the University of Colorado oncologist Wells Messersmith, have said they have never witnessed a 5-FU death.

In European hospitals, the practice is to start patients with a half- or quarter-dose of 5-FU if tests show a patient is a poor metabolizer, then raise the dose if the patient responds well to the drug. Advocates for the approach say American oncology leaders are dragging their feet unnecessarily, and harming people in the process.

“I think it’s the intransigence of people sitting on these panels, the mindset of ‘We are oncologists, drugs are our tools, we don’t want to go looking for reasons not to use our tools,’” said Gabriel Brooks, an oncologist and researcher at the Dartmouth Cancer Center.

Oncologists are accustomed to chemotherapy’s toxicity and tend to have a “no pain, no gain” attitude, he said. 5-FU has been in use since the 1950s.

Yet “anybody who’s had a patient die like this will want to test everyone,” said Robert Diasio of the Mayo Clinic, who helped carry out major studies of the genetic deficiency in 1988.

Oncologists often deploy genetic tests to match tumors in cancer patients with the expensive drugs used to shrink them. But the same can’t always be said for gene tests aimed at improving safety, said Mark Fleury, policy director at the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Action Network.

When a test can show whether a new drug is appropriate, “there are a lot more forces aligned to ensure that testing is done,” he said. “The same stakeholders and forces are not involved” with a generic like 5-FU, first approved in 1962, and costing roughly $17 for a month’s treatment.

Oncology is not the only area in medicine in which scientific advances, many of them taxpayer-funded, lag in implementation. For instance, few cardiologists test patients before they go on Plavix, a brand name for the anti-blood-clotting agent clopidogrel, although it doesn’t prevent blood clots as it’s supposed to in a quarter of the 4 million Americans prescribed it each year. In 2021, the state of Hawaii won an $834 million judgment from drugmakers it accused of falsely advertising the drug as safe and effective for Native Hawaiians, more than half of whom lack the main enzyme to process clopidogrel.

The fluoropyrimidine enzyme deficiency numbers are smaller — and people with the deficiency aren’t at severe risk if they use topical cream forms of the drug for skin cancers. Yet even a single miserable, medically caused death was meaningful to the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where Carol Rosen was among more than 1,000 patients treated with fluoropyrimidine in 2021.

Her daughter was grief-stricken and furious after Rosen’s death. “I wanted to sue the hospital. I wanted to sue the oncologist,” Murray said. “But I realized that wasn’t what my mom would want.”

Instead, she wrote Dana-Farber’s chief quality officer, Joe Jacobson, urging routine testing. He responded the same day, and the hospital quickly adopted a testing system that now covers more than 90% of prospective fluoropyrimidine patients. About 50 patients with risky variants were detected in the first 10 months, Jacobson said.

Dana-Farber uses a Mayo Clinic test that searches for eight potentially dangerous variants of the relevant gene. Veterans Affairs hospitals use a 11-variant test, while most others check for only four variants.

Different Tests May Be Needed for Different Ancestries

The more variants a test screens for, the better the chance of finding rarer gene forms in ethnically diverse populations. For example, different variants are responsible for the worst deficiencies in people of African and European ancestry, respectively. There are tests that scan for hundreds of variants that might slow metabolism of the drug, but they take longer and cost more.

These are bitter facts for Scott Kapoor, a Toronto-area emergency room physician whose brother, Anil Kapoor, died in February 2023 of 5-FU poisoning.

Anil Kapoor was a well-known urologist and surgeon, an outgoing speaker, researcher, clinician, and irreverent friend whose funeral drew hundreds. His death at age 58, only weeks after he was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer, stunned and infuriated his family.

In Ontario, where Kapoor was treated, the health system had just begun testing for four gene variants discovered in studies of mostly European populations. Anil Kapoor and his siblings, the Canadian-born children of Indian immigrants, carry a gene form that’s apparently associated with South Asian ancestry.

Scott Kapoor supports broader testing for the defect — only about half of Toronto’s inhabitants are of European descent — and argues that an antidote to fluoropyrimidine poisoning, approved by the FDA in 2015, should be on hand. However, it works only for a few days after ingestion of the drug and definitive symptoms often take longer to emerge.

Most importantly, he said, patients must be aware of the risk. “You tell them, ‘I am going to give you a drug with a 1 in 1,000 chance of killing you. You can take this test. Most patients would be, ‘I want to get that test and I’ll pay for it,’ or they’d just say, ‘Cut the dose in half.’”

Alan Venook, the University of California-San Francisco oncologist who co-chairs the panel that sets guidelines for colorectal cancers at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, has led resistance to mandatory testing because the answers provided by the test, in his view, are often murky and could lead to undertreatment.

“If one patient is not cured, then you giveth and you taketh away,” he said. “Maybe you took it away by not giving adequate treatment.”

Instead of testing and potentially cutting a first dose of curative therapy, “I err on the latter, acknowledging they will get sick,” he said. About 25 years ago, one of his patients died of 5-FU toxicity and “I regret that dearly,” he said. “But unhelpful information may lead us in the wrong direction.”

In September, seven months after his brother’s death, Kapoor was boarding a cruise ship on the Tyrrhenian Sea near Rome when he happened to meet a woman whose husband, Atlanta municipal judge Gary Markwell, had died the year before after taking a single 5-FU dose at age 77.

“I was like … that’s exactly what happened to my brother.”

Murray senses momentum toward mandatory testing. In 2022, the Oregon Health & Science University paid $1 million to settle a suit after an overdose death.

“What’s going to break that barrier is the lawsuits, and the big institutions like Dana-Farber who are implementing programs and seeing them succeed,” she said. “I think providers are going to feel kind of bullied into a corner. They’re going to continue to hear from families and they are going to have to do something about it.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Brain Wash – by Dr. David Perlmutter, Dr. Austin Perlmutter, and Kristen Loberg

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may be familiar with the lead author of this book, Dr. David Perlmutter, as a big name in the world of preventative healthcare. A lot of his work has focused specifically on carbohydrate metabolism, and he is as associated with grains and he is with brains. This book focuses on the latter.

Dr. Perlmutter et al. take a methodical look at all that is ailing our brains in this modern world, and systematically lay out a plan for improving each aspect.

The advice is far from just dietary, though the chapter on diet takes a clear stance:

❝The food you eat and the beverages you drink change your emotions, your thoughts, and the way you perceive the world❞

The style is explanatory, and the book can be read comfortably as a “sit down and read it cover to cover” book; it’s an enjoyable, informative, and useful read.

Bottom line: if you’d like to give your brain a gentle overhaul, this is the one-stop-shop book to give you the tools to do just that.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

White Bread vs White Pasta – Which Is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing a white bread to a white pasta, we picked the pasta.

Why?

Neither are great for the health! But like for like, the glycemic index of the bread is usually around 150% of the glycemic index for pasta.

All that said, we heartily recommend going for wholegrain in either case!

Bonus tip: cooking pasta “al dente”, so it is still at least a little firm to the bite, results in a lower GI compared to being boiled to death.

Bonus bonus tip: letting pasta cool increases resistant starches. You can then reheat the pasta without losing this benefit.

Please don’t put it in the microwave though; you will make an Italian cry. Instead, simply put it in a colander and pour boiling water over it, and then serve in your usual manner (a good approach if serving it separately is: put it in the serving bowl/dish/pan, drizzle a little extra virgin olive oil and a little cracked black pepper, stir to mix those in, and serve)

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

I have a stuffy nose, how can I tell if it’s hay fever, COVID or something else?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hay fever (also called allergic rhinitis) affects 24% of Australians. Symptoms include sneezing, a runny nose (which may feel blocked or stuffy) and itchy eyes. People can also experience an itchy nose, throat or ears.

But COVID is still spreading, and other viruses can cause cold-like symptoms. So how do you know which one you’ve got?

Lysenko Andrii/Shutterstock Remind me, how does hay fever cause symptoms?

Hay fever happens when a person has become “sensitised” to an allergen trigger. This means a person’s body is always primed to react to this trigger.

Triggers can include allergens in the air (such as pollen from trees, grasses and flowers), mould spores, animals or house dust mites which mostly live in people’s mattresses and bedding, and feed on shed skin.

When the body is exposed to the trigger, it produces IgE (immunoglobulin E) antibodies. These cause the release of many of the body’s own chemicals, including histamine, which result in hay fever symptoms.

People who have asthma may find their asthma symptoms (cough, wheeze, tight chest or trouble breathing) worsen when exposed to airborne allergens. Spring and sometimes into summer can be the worst time for people with grass, tree or flower allergies.

However, animal and house dust mite symptoms usually happen year-round.

Ryegrass pollen is a common culprit. bangku ceria/Shutterstock What else might be causing my symptoms?

Hay fever does not cause a fever, sore throat, muscle aches and pains, weakness, loss of taste or smell, nor does it cause you to cough up mucus.

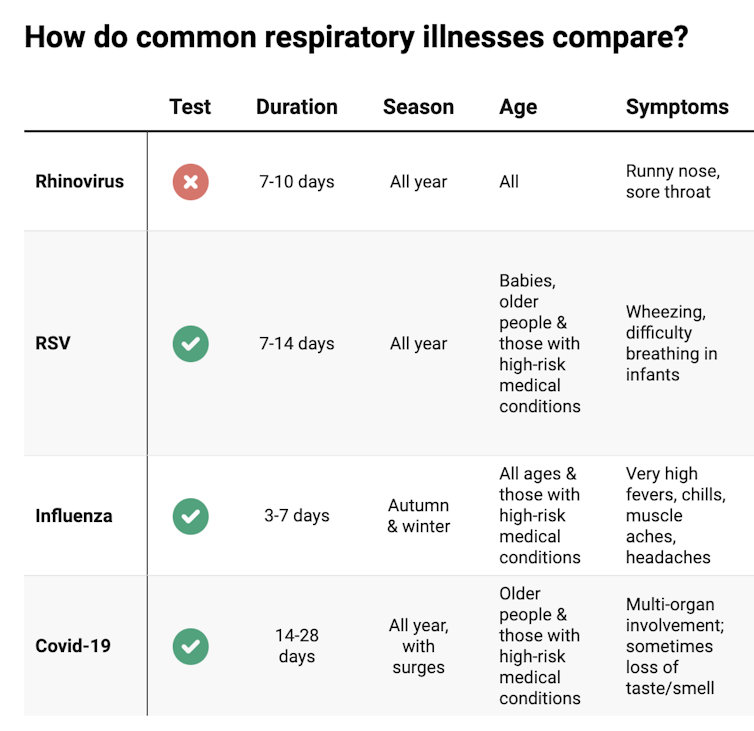

These symptoms are likely to be caused by a virus, such as COVID, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or a “cold” (often caused by rhinoviruses). These conditions can occur all year round, with some overlap of symptoms:

Natasha Yates/The Conversation COVID still surrounds us. RSV and influenza rates appear higher than before the COVID pandemic, but it may be due to more testing.

So if you have a fever, sore throat, muscle aches/pains, weakness, fatigue, or are coughing up mucus, stay home and avoid mixing with others to limit transmission.

People with COVID symptoms can take a rapid antigen test (RAT), ideally when symptoms start, then isolate until symptoms disappear. One negative RAT alone can’t rule out COVID if symptoms are still present, so test again 24–48 hours after your initial test if symptoms persist.

You can now test yourself for COVID, RSV and influenza in a combined RAT. But again, a negative test doesn’t rule out the virus. If your symptoms continue, test again 24–48 hours after the previous test.

If it’s hay fever, how do I treat it?

Treatment involves blocking the body’s histamine release, by taking antihistamine medication which helps reduce the symptoms.

Doctors, nurse practitioners and pharmacists can develop a hay fever care plan. This may include using a nasal spray containing a topical corticosteroid to help reduce the swelling inside the nose, which causes stuffiness or blockage.

Nasal sprays need to delivered using correct technique and used over several weeks to work properly. Often these sprays can also help lessen the itchy eyes of hay fever.

Drying bed linen and pyjamas inside during spring can lessen symptoms, as can putting a smear of Vaseline in the nostrils when going outside. Pollen sticks to the Vaseline, and gently blowing your nose later removes it.

People with asthma should also have an asthma plan, created by their doctor or nurse practitioner, explaining how to adjust their asthma reliever and preventer medications in hay fever seasons or on allergen exposure.

People with asthma also need to be alert for thunderstorms, where pollens can burst into tinier particles, be inhaled deeper in the lungs and cause a severe asthma attack, and even death.

What if it’s COVID, RSV or the flu?

Australians aged 70 and over and others with underlying health conditions who test positive for COVID are eligible for antivirals to reduce their chance of severe illness.

Most other people with COVID, RSV and influenza will recover at home with rest, fluids and paracetamol to relieve symptoms. However some groups are at greater risk of serious illness and may require additional treatment or hospitalisation.

For RSV, this includes premature infants, babies 12 months and younger, children under two who have other medical conditions, adults over 75, people with heart and lung conditions, or health conditions that lessens the immune system response.

For influenza, people at higher risk of severe illness are pregnant women, Aboriginal people, people under five or over 65 years, or people with long-term medical conditions, such as kidney, heart, lung or liver disease, diabetes and decreased immunity.

If you’re concerned about severe symptoms of COVID, RSV or influenza, consult your doctor or call 000 in an emergency.

If your symptoms are mild but persist, and you’re not sure what’s causing them, book an appointment with your doctor or nurse practitioner. Although hay fever season is here, we need to avoid spreading other serious infectious.

For more information, you can call the healthdirect helpline on 1800 022 222 (known as NURSE-ON-CALL in Victoria); use the online Symptom Checker; or visit healthdirect.gov.au or the Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy.

Deryn Thompson, Eczema and Allergy Nurse; Lecturer, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: