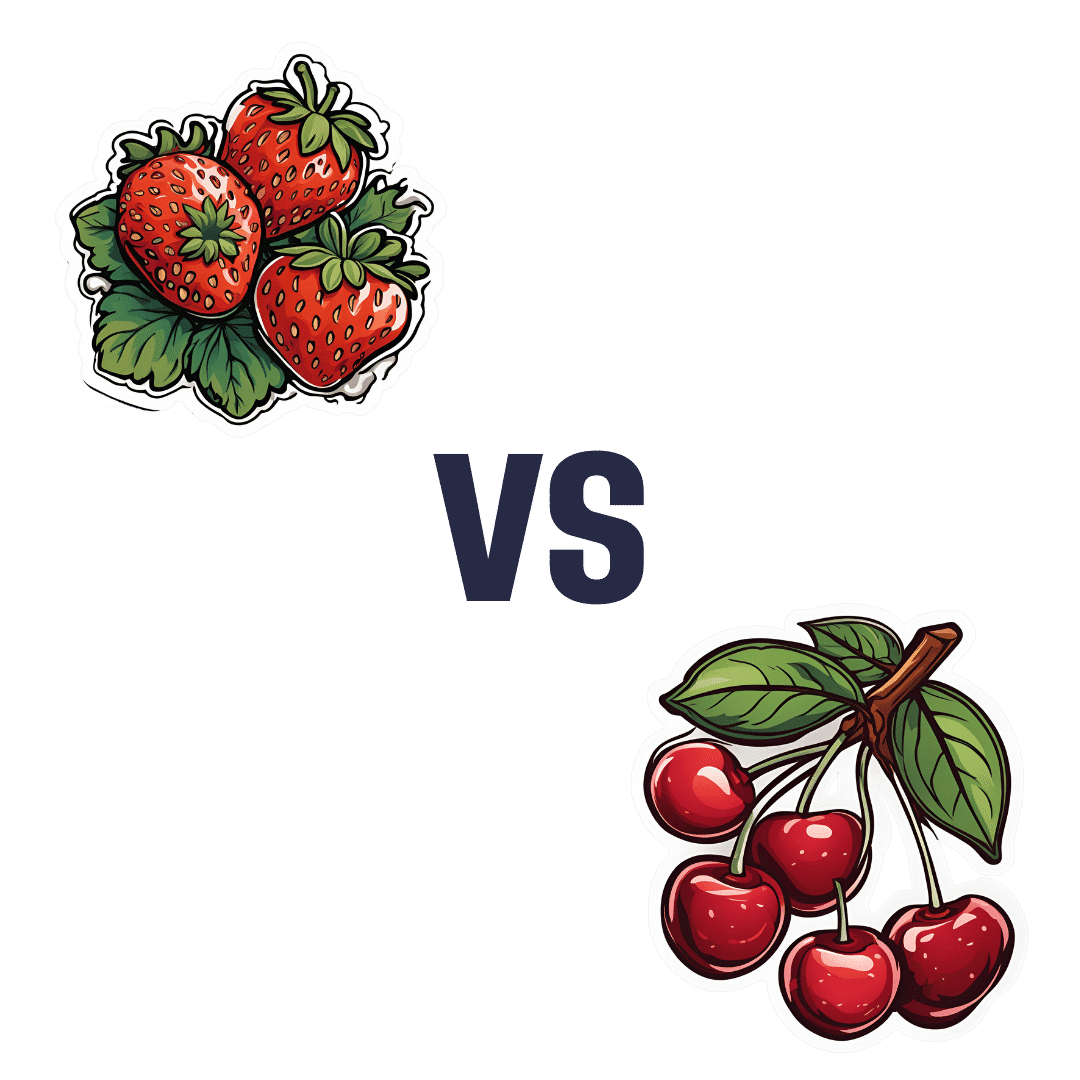

Strawberries vs Cherries – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing strawberries to cherries, we picked the cherries.

Why?

Both are great, and an argument could be made for either! But here’s our rationale:

In terms of macros, as with most fruits they are both mostly water, and have similar carbs and fiber. Nominally, cherries have the lower glycemic index, so we could call this category nominally a win for cherries, but honestly, they’re both low-GI foods and nobody is getting metabolic disease from eating strawberries, so it’s fairer to consider this category a tie.

Looking at the vitamins, strawberries have more of vitamins C, B9, E, and K, while cherries have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, and choline. Thus, a modest win for cherries here.

When it comes to minerals, strawberries see their day: strawberries have more iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus, while cherries have more calcium, copper, and potassium. By the numbers, a win for strawberries.

So far, so tied!

What swings it into cherries’ favor is cherries’ slew of specific phytochemical benefits, including cherry-specific anti-inflammatory properties, sleep-improving abilities, and post-exercise recovery boosts, as well as anti-diabetic benefits above and beyond the normal “this is a fruit” level.

In short, both are very respectable fruits, but cherries have some extra qualities that are just special.

Of course, as ever, enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Cherries’ Health Benefits Simply Pop

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

We’re the ‘allergy capital of the world’. But we don’t know why food allergies are so common in Australian children

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Australia has often been called the “allergy capital of the world”.

An estimated one in ten Australian children develop a food allergy in their first 12 months of life. Research has previously suggested food allergies are more common in infants in Australia than infants living in Europe, the United States or Asia.

So why are food allergies so common in Australia? We don’t know exactly – but local researchers are making progress in understanding childhood allergies all the time.

Miljan Zivkovic/Shutterstock What causes food allergies?

There are many different types of reactions to foods. When we refer to food allergies in this article, we’re talking about something called IgE-mediated food allergy. This type of allergy is caused by an immune response to a particular food.

Reactions can occur within minutes of eating the food and may include swelling of the face, lips or eyes, “hives” or welts on the skin, and vomiting. Signs of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) include difficulty breathing, swelling of the tongue, swelling in the throat, wheeze or persistent cough, difficulty talking or a hoarse voice, and persistent dizziness or collapse.

Recent results from Australia’s large, long-running food allergy study, HealthNuts, show one in ten one-year-olds have a food allergy, while around six in 100 children have a food allergy at age ten.

A food allergy can present with skin reactions. comzeal images/Shutterstock In Australia, the most common allergy-causing foods include eggs, peanuts, cow’s milk, shellfish (for example, prawn and lobster), fish, tree nuts (for example, walnuts and cashews), soybeans and wheat.

Allergies to foods like eggs, peanuts and cow’s milk often present for the first time in infancy, while allergies to fish and shellfish may be more common later in life. While most children will outgrow their allergies to eggs and milk, allergy to peanuts is more likely to be lifelong.

Findings from HealthNuts showed around three in ten children grew out of their peanut allergy by age six, compared to nine in ten children with an allergy to egg.

Are food allergies becoming more common?

Food allergies seem to have become more common in many countries around the world over recent decades. The exact timing of this increase is not clear, because in most countries food allergies were not well measured 40 or 50 years ago.

We don’t know exactly why food allergies are so common in Australia, or why we’re seeing a rise around the world, despite extensive research.

But possible reasons for rising allergies around the world include changes in the diets of mothers and infants and increasing sanitisation, leading to fewer infections as well as less exposure to “good” bacteria. In Australia, factors such as increasing vitamin D deficiency among infants and high levels of migration to the country could play a role.

In several Australian studies, children born in Australia to parents who were born in Asia have higher rates of food allergies compared to non-Asian children. On the other hand, children who were born in Asia and later migrated to Australia appear to have a lower risk of nut allergies.

Meanwhile, studies have shown that having pet dogs and siblings as a young child may reduce the risk of food allergies. This might be because having pet dogs and siblings increases contact with a range of bacteria and other organisms.

This evidence suggests that both genetics and environment play a role in the development of food allergies.

We also know that infants with eczema are more likely to develop a food allergy, and trials are underway to see whether this link can be broken.

Can I do anything to prevent food allergies in my kids?

One of the questions we are asked most often by parents is “can we do anything to prevent food allergies?”.

We now know introducing peanuts and eggs from around six months of age makes it less likely that an infant will develop an allergy to these foods. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy introduced guidelines recommending giving common allergy-causing foods including peanut and egg in the first year of life in 2016.

Our research has shown this advice had excellent uptake and may have slowed the rise in food allergies in Australia. There was no increase in peanut allergies between 2007–11 to 2018–19.

Introducing other common allergy-causing foods in the first year of life may also be helpful, although the evidence for this is not as strong compared with peanuts and eggs.

Giving kids peanuts early can reduce the risk of a peanut allergy. Madame-Moustache/Shutterstock What next?

Unfortunately, some infants will develop food allergies even when the relevant foods are introduced in the first year of life. Managing food allergies can be a significant burden for children and families.

Several Australian trials are currently underway testing new strategies to prevent food allergies. A large trial, soon to be completed, is testing whether vitamin D supplements in infants reduce the risk of food allergies.

Another trial is testing whether the amount of eggs and peanuts a mother eats during pregnancy and breastfeeding has an influence on whether or not her baby will develop food allergies.

For most people with food allergies, avoidance of their known allergens remains the standard of care. Oral immunotherapy, which involves gradually increasing amounts of food allergen given under medical supervision, is beginning to be offered in some facilities around Australia. However, current oral immunotherapy methods have potential side effects (including allergic reactions), can involve high time commitment and cost, and don’t cure food allergies.

There is hope on the horizon for new food allergy treatments. Multiple clinical trials are underway around Australia aiming to develop safer and more effective treatments for people with food allergies.

Jennifer Koplin, Group Leader, Childhood Allergy & Epidemiology, The University of Queensland and Desalegn Markos Shifti, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Child Health Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Heart Healthy Diet Plan – by Stephen William

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve covered heart-healthy cooking books before, but variety is good, and boredom is an enemy of health, so let’s shake it up with a fresh stack of recipes!

After a brief overview of the relevant science (which if you’re a regular 10almonds reader, probably won’t be new to you), the author takes the reader on a 28-day journey. Yes, we know the subtitle says 30 days, but unless they carefully hid the other two days somewhere we didn’t find, there are “only” 28 inside. Perhaps the publisher heard it was a month and took creative license. Or maybe there’s a different edition. Either way…

Rather than merely giving a diet plan (though yes, he also does that), he gives a wide range of “spotlight ingredients”, such that many of the recipes, while great in and of themselves, can also be jumping-off points for those of us who like to take recipes and immediately do our own things to them.

Each day gets a breakfast, lunch, dinner, and he also covers drinks, desserts, and such like.

Notwithstanding the cover art being a lot of plants, the recipes are not entirely plant-based; there are a selection of fish dishes (and other seafood, e.g. shrimp) and also some dairy products (e.g. Greek yoghurt). The recipes are certainly very “plant-forward” though and many are just plants. If you’re a strict vegan though, this probably isn’t the book for you.

Bottom line: if you’d like to cook heart-healthy but are often stuck wondering “aaah, what to cook again today?”, then this is the book to get you out of any culinary creative block!

Click here to check out the Heart Healthy Diet Plan, and widen your heart-healthy repertoire!

Share This Post

-

How Too Much Salt May Lead To Organ Failure

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Salt’s Health Risks… More Than Just Heart Disease!

It’s been well-established for a long time that too much salt is bad for cardiovascular health. It can lead to high blood pressure, which in turn can lead to many problems, including heart attacks.

A team of researchers has found that in addition to this, it may be damaging your organs themselves.

This is because high salt levels peel away the surfaces of blood vessels. How does this harm your organs? Because it’s through those walls that nutrients are selectively passed to where they need to be—mostly your organs. So, too much salt can indirectly starve your organs of the nutrients they need to survive. And you absolutely do not want your organs to fail!

❝We’ve identified new biomarkers for diagnosing blood vessel damage, identifying patients at risk of heart attack and stroke, and developing new drug targets for therapy for a range of blood vessel diseases, including heart, kidney and lung diseases as well as dementia❞

~ Newman Sze, Canada Research Chair in Mechanisms of Health and Disease, and lead researcher on this study.

See the evidence for yourself: Endothelial Damage Arising From High Salt Hypertension Is Elucidated by Vascular Bed Systematic Profiling

Diets high in salt are a huge problem in Canada, North America as a whole, and around the world. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report released March 9, Canadians consume 9.1 grams of salt per day.

Read: WHO global report on sodium intake reduction

You may be wondering: who is eating over 9g of salt per day?

And the answer is: mostly, people who don’t notice how much salt is already in processed foods… don’t see it, and don’t think about it.

Meanwhile, the WHO recommends the average person to consume no more than five grams, or one teaspoon, of salt per day.

Read more: Massive efforts needed to reduce salt intake and protect lives

The American Heart Association, tasked with improving public health with respect to the #1 killer of Americans (it’s also the #1 killer worldwide—but that’s not the AHA’s problem), goes further! It recommends no more than 2.3g per day, and ideally, no more than 1.5g per day.

Some handy rules-of-thumb

Here are sodium-related terms you may see on food packages:

- Salt/Sodium-Free = Less than 5mg of sodium per serving

- Very Low Sodium = 35mg or less per serving

- Low Sodium = 140mg or less per serving

- Reduced Sodium = At least 25% less sodium per serving than the usual sodium level

- Light in Sodium or Lightly Salted = At least 50% less sodium than the regular product

Confused by milligrams? Instead of remembering how many places to move the decimal point (and potentially getting an “out by an order of magnitude error—we’ve all been there!), think of the 1.5g total allowance as being 1500mg.

See also: How much sodium should I eat per day? ← from the American Heart Association

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Pistachios vs Cashews – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pistachios to cashews, we picked the pistachios.

Why?

In terms of macros, both are great sources of protein and healthy fats, and considered head-to-head:

- pistachios have slightly more protein, but it’s close

- pistachios have slightly more (health) fat, but it’s close

- cashews have slightly more carbs, but it’s close

- pistachios have a lot more fiber (more than 3x more!)

All in all, both have a good macro balance, but pistachios win easily on account of the fiber, as well as the slight edge for protein and fats.

When it comes to vitamins, pistachios have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, C, & E.

Cashews do have more vitamin B5, also called pantothenic acid, pantothenic literally meaning “from everywhere”. Guess what’s not a common deficiency to have!

So pistachios win easily on vitamins, too.

In the category of minerals, things are more balanced, though cashews have a slight edge. Pistachios have more notably more calcium and potassium, while cashews have notably more selenium, zinc, and magnesium.

Both of these nuts have anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and anti-cancer benefits, often from different phytochemicals, but with similar levels of usefulness.

Taking everything into account, however, one nut comes out in the clear lead, mostly due to its much higher fiber content and better vitamin profile, and that’s the pistachios.

Want to learn more?

Check out:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

5 Things You Can Change About Your Personality (But: Should You?)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are many personality-typing systems that, with varying degrees of validity*, aim to describe a person’s personality.

*and often pseudoscience:

- sometimes obviously so like astrology

- sometimes dressed up in clinical words like the Meyers-Briggs

- sometimes openly, per “this is not science but you may find it useful to frame things this way”, like the Enneagram

There is currently one kind of personality-typing system (with some minor variations) that is used in the actual field of clinical psychology, specifically under the umbrella of “trait theory”, and that is…

The “Big Five” personality traits

Also called the OCEAN or CANOE model, based on its 5 components:

- openness to experience: inventive/curious rather than consistent/cautious

- conscientiousness: efficient/organized rather than extravagant/careless

- extroversion: outgoing/energetic rather than solitary/reserved

- agreeableness: friendly/compassionate rather than critical/judgmental

- neuroticism: sensitive/nervous rather than resilient/confident

The latter (neuroticism) is not to be confused with neurosis, which is very different and beyond the scope of today’s article.

Note that some of these seem more positive/negative than others at a glance, but really, any of these could be a virtue or a vice depending on specifics or extremity.

For scientific reference, here’s an example paper:

The Big Five Personality Factors and Personal Values

Quick self-assessment

There are of course many lengthy questionnaires for this, but in the interests of expediency:

Take a moment to rate yourself as honestly as you can, on a scale of 1–10, for each of those components, with 10 being highest for the named trait.

For example, this writer gives herself: O7, C6, E3, A8, N2 (in other words I’d say I’m fairly open, moderately conscientious, on the reserved side, quite agreeable, and quite resilient)

Now, put your rating aside (in your phone’s notes app is fine, if you hadn’t written it down already) and forget about it for the moment, because we want you to do the next exercise from scratch.

Who would you be, at your best?

Now imagine your perfect idealized self, the best you could ever be, with no constraints.

Take a moment to rate your idealized self’s personality, on a scale of 1–10, for each of those components, with 10 being highest for the named trait.

For example, this writer picks: O9, C10, E5, A8, N1.

Maybe this, or maybe your own idealized self’s personality, will surprise you. That some traits might already be perfect for you already; others might just be nudged a little here or there; maybe there’s some big change you’d like. Chances are you didn’t go for a string of 10s or 1s (though if you did, you do you; there are no wrong answers here as this one is about your preferences).

We become who we practice being

There are some aspects of personality that can naturally change with age. For example:

- confidence/resilience will usually gradually increase with age due to life experience (politely overlook teenagers’ bravado; they are usually a bundle of nerves inside, resulting in the overcompensatory displays of confidence)

- openness to experience may decrease with age, as we can get into a rut of thinking/acting a certain way, and/or simply consciously decide that our position on something is already complete and does not need revision.

But, we can decide for ourselves how to nudge our “Big Five” traits, for example:

- We can make a point of seeking out new experiences, and considering new ideas, or develop strategies for reining ourselves in

- We can use systems to improve our organization, or go out of our way to introduce a little well-placed chaos

- We can “put ourselves out there” socially, or make the decision to decline more social invitations because we simply don’t want to

- We can make a habit of thinking kindly of others and ourselves, or we can consciously detach ourselves and look on the cynical side more

- We can build on our strengths and eliminate our weaknesses, or lean into uncomfortable emotions

Some of those may provoke a “why would anyone want to…?” response, but the truth is we are all different. An artist and a police officer may have very different goals for who they want to be as a person, for example.

Interventions to change personality can and do work:

A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention

There are many ways to go about “being the change we want to see” in ourselves, and yes there can be a degree of “fake it until you make it” if that works for you, but it doesn’t have to be so. It can also simply be a matter of setting yourself reminders about the things that are most important to you.

Writer’s example: pinned above my digital workspace I have a note from my late beloved, written just under a week before death. The final line reads, “keep being the good person that you are” (on a human level, the whole note is uplifting and soothing to me and makes me smile and remember the love we shared; or to put it in clinical terms, it promotes high agreeableness, low neuroticism).

Other examples could be a daily practice of gratitude (promotes lower neuroticism), or going out of your way to speak to your neighbors (promotes higher extraversion), signing up for a new educational course (promotes higher openness) or downloading a budgeting app (promotes higher conscientiousness).

In short: be the person you want to be, and be that person deliberately, because you can.

Some resources that may help for each of the 5 traits:

- Curiosity Kills The Neurodegeneration

- How (And Why) To Train Your Pre-Frontal Cortex

- How To Beat Loneliness & Isolation

- Optimism Seriously Increases Longevity!

- Building Psychological Resilience (Without Undue Hardship)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Even small diet tweaks can lead to sustainable weight loss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s a well-known fact that to lose weight, you either need to eat less or move more. But how many calories do you really need to cut out of your diet each day to lose weight? It may be less than you think.

To determine how much energy (calories) your body requires, you need to calculate your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE). This is comprised of your basal metabolic rate (BMR) – the energy needed to sustain your body’s metabolic processes at rest – and your physical activity level. Many online calculators can help determine your daily calorie needs.

If you reduce your energy intake (or increase the amount you burn through exercise) by 500-1,000 calories per day, you’ll see a weekly weight loss of around one pound (0.45kg).

But studies show that even small calorie deficits (of 100-200 calories daily) can lead to long-term, sustainable weight-loss success. And although you might not lose as much weight in the short-term by only decreasing calories slightly each day, these gradual reductions are more effective than drastic cuts as they tend to be easier to stick with.

Small diet changes can still lead to weight loss in the long run. Monkey Business Images/ Shutterstock Hormonal changes

When you decrease your calorie intake, the body’s BMR often decreases. This phenomenon is known as adaptive thermogenesis. This adaptation slows down weight loss so the body can conserve energy in response to what it perceives as starvation. This can lead to a weight-loss plateau – even when calorie intake remains reduced.

Caloric restriction can also lead to hormonal changes that influence metabolism and appetite. For instance, thyroid hormones, which regulate metabolism, can decrease – leading to a slower metabolic rate. Additionally, leptin levels drop, reducing satiety, increasing hunger and decreasing metabolic rate.

Ghrelin, known as the “hunger hormone”, also increases when caloric intake is reduced, signalling the brain to stimulate appetite and increase food intake. Higher ghrelin levels make it challenging to maintain a reduced calorie diet, as the body constantly feels hungrier.

Insulin, which helps regulate blood sugar levels and fat storage, can improve in sensitivity when we reduce calorie intake. But sometimes, insulin levels decrease instead, affecting metabolism and leading to a reduction in daily energy expenditure. Cortisol, the stress hormone, can also spike – especially when we’re in a significant caloric deficit. This may break down muscles and lead to fat retention, particularly in the stomach.

Lastly, hormones such as peptide YY and cholecystokinin, which make us feel full when we’ve eaten, can decrease when we lower calorie intake. This may make us feel hungrier.

Fortunately, there are many things we can do to address these metabolic adaptations so we can continue losing weight.

Weight loss strategies

Maintaining muscle mass (either through resistance training or eating plenty of protein) is essential to counteract the physiological adaptations that slow weight loss down. This is because muscle burns more calories at rest compared to fat tissue – which may help mitigate decreased metabolic rate.

Portion control is one way of decreasing your daily calorie intake. Fevziie/ Shutterstock Gradual caloric restriction (reducing daily calories by only around 200-300 a day), focusing on nutrient-dense foods (particularly those high in protein and fibre), and eating regular meals can all also help to mitigate these hormonal challenges.

But if you aren’t someone who wants to track calories each day, here are some easy strategies that can help you decrease daily calorie intake without thinking too much about it:

1. Portion control: reducing portion sizes is a straightforward way of reducing calorie intake. Use smaller plates or measure serving sizes to help reduce daily calorie intake.

2. Healthy swaps: substituting high-calorie foods with lower-calorie alternatives can help reduce overall caloric intake without feeling deprived. For example, replacing sugary snacks with fruits or swapping soda with water can make a substantial difference to your calorie intake. Fibre-rich foods can also reduce the calorie density of your meal.

3. Mindful eating: practising mindful eating involves paying attention to hunger and fullness cues, eating slowly, and avoiding distractions during meals. This approach helps prevent overeating and promotes better control over food intake.

4. Have some water: having a drink with your meal can increase satiety and reduce total food intake at a given meal. In addition, replacing sugary beverages with water has been shown to reduce calorie intake from sugars.

4. Intermittent fasting: restricting eating to specific windows can reduce your caloric intake and have positive effects on your metabolism. There are different types of intermittent fasting you can do, but one of the easiest types is restricting your mealtimes to a specific window of time (such as only eating between 12 noon and 8pm). This reduces night-time snacking, so is particularly helpful if you tend to get the snacks out late in the evening.

Long-term behavioural changes are crucial for maintaining weight loss. Successful strategies include regular physical activity, continued mindful eating, and periodically being diligent about your weight and food intake. Having a support system to help you stay on track can also play a big role in helping you maintain weight loss.

Modest weight loss of 5-10% body weight in people who are overweight or obese offers significant health benefits, including improved metabolic health and reduced risk of chronic diseases. But it can be hard to lose weight – especially given all the adaptations our body has to prevent it from happening.

Thankfully, small, sustainable changes that lead to gradual weight loss appear to be more effective in the long run, compared with more drastic lifestyle changes.

Alexandra Cremona, Lecturer, Human Nutrition and Dietetics, University of Limerick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: