Is A Visible Six-Pack Obtainable Regardless Of Genetic Predisposition?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝Is it possible for anyone to get 6-pack abs (even if genetics makes it easier or harder) and how much does it matter for health e.g. waist size etc?❞

Let’s break it down into two parts:

Is it possible for anyone to get 6-pack abs (even if genetics makes it easier or harder)?

Short answer: no

First, a quick anatomy lesson: while “abs” (abdominal muscles) are considered in the plural and indeed they are, what we see as a six-pack is actually only one muscle, the rectus abdominis, which is nestled in between other abdominal muscles that are beyond the scope of our answer here.

The reason that the rectus abdominis looks like six muscles is because there are bands of fascia (connective tissue) lying over it, so we see where it bulges between those bands.

The main difference genes make are as follows:

- Number of fascia bands (and thus the reason that some people get a four-, six-, eight-, or rarely, even ten-pack). Obviously, no amount of training can change this number, any more than doing extra bicep curls will grow you additional arms.

- Density of muscle fibers. Some people have what has been called “superathlete muscle type”, which, while prized by Olympians and other athletes, is on bodybuilding forums less glamorously called being a “hard gainer”. What this means is that muscle fibers are denser, so while training will make muscles stronger, you won’t see as much difference in size. This means that size for size, the person with this muscle type will always be stronger than someone the same size without it, but that may be annoying if you’re trying to build visible definition.

- Twitch type of muscle fibers. Some people have more fast-twitch fibers, some have more slow-twitch fibers. Fast-twitch fibers are better suited for visible abs (and, as the name suggests, quick changes between contracting and relaxing). Slow-twitch fibers are better for endurance, but yield less bulky muscles.

- Inclination to subcutaneous fat storage. This is by no means purely genetic; hormones make the biggest difference, followed by diet. But, genes are an influencing factor, and if your body fat percentage is inclined to be higher than someone else’s, then it’ll take more work to see muscle definition under that fat.

The first of those items is why our simple answer is “no”; because some people are destined to, if muscle is visible, have a four-, eight, or (rarely) ten-pack, making a six-pack unobtainable.

It’s worth noting here that while a bigger number is more highly prized aesthetically, there is literally zero difference healthwise or in terms of performance, because it’s nothing to do with the muscle, and is only about the fascia layout.

The density of muscle fibers is again purely genetic, but it only makes things easier or harder; this part’s not impossible for anyone.

The inclination to subcutaneous fat storage is by far the most modifiable factor, and the thus most readily overcome, if you feel so inclined. That doesn’t mean it will necessarily be easy! But it does mean that it’s relatively less difficult than the others.

How much does it matter for health, e.g. waist size etc?

As you may have gathered from the above, having a six-pack (or indeed a differently-numbered “pack”, if that be your genetic lot) makes no important difference to health:

- The fascia layout is completely irrelevant to health

- The muscle fiber types do make a difference to athletic performance, but not general health when at rest

- The subcutaneous fat storage is a health factor, but probably not how most people think

Healthy body fat percentages are (assuming normal hormones) in the range of 20–25% for women and 15–20% for men.

For most people, having clearly visible abs requires going below those healthy levels. For most people, that’s not optimally healthy. And those you see on magazine covers or in bodybuilding competitions are usually acutely dehydrated for the photo, which is of course not good. They will rehydrate after the shoot.

However, waist size (especially as a ratio, compared to hip size) is very important to health. This has less to do with subcutaneous fat, though, and is more to do with visceral belly fat, which goes under the muscles and thus does not obscure them:

Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It

One final note: fat notwithstanding, and aesthetics notwithstanding, having a strong core is very good for general health; it helps keeps one’s internal organs in place and well-protected, and improves stability, making falls less likely as we get older. Additionally, having muscle improves our metabolic base rate, which is good for our heart. Abs are just one part of core strength (the back being important too, for example), but should not be neglected.

Top-tier exercises to do include planks, and hanging leg raises (i.e. hang from some support, such as a chin-up bar, and raise your legs, which counterintuitively works your abs a lot more than your legs).

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Train For The Event Of Your Life!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mobility As A Sporting Pursuit

As we get older, it becomes increasingly important to treat life like a sporting event. By this we mean:

As an “athlete of life”, there are always events coming up for which we need to train. Many of these events will be surprise tests!

Such events/tests might include:

- Not slipping in the shower and breaking a hip (or worse)

- Reaching an item from a high shelf without tearing a ligament

- Getting out of the car at an awkward angle without popping a vertebra

- Climbing stairs without passing out light-headed at the top

- Descending stairs without making it a sled-ride-without-a-sled

…and many more.

Train for these athletic events now

Not necessarily this very second; we appreciate you finishing reading first. But, now generally in your life, not after the first time you fail such a test; it can (and if we’re not attentive: will) indeed happen to us all.

With regard to falling, you might like to revisit our…

…which covers how to not fall, and to not injure yourself if you do.

You’ll also want to be able to keep control of your legs (without them buckling) all the way between standing and being on the ground.

Slav squats or sitting squats (same exercise, different names, amongst others) are great for building and maintaining this kind of strength and suppleness:

(Click here for a refresher if you haven’t recently seen Zuzka’s excellent video explaining how to do this, especially if it’s initially difficult for you, “The Most Anti-Aging Exercise”)

this exercise is, by the way, great for pretty much everything below the waist!

You will also want to do resistance exercises to keep your body robust:

Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

And as for those shoulders? If it is convenient for you to go swimming, then backstroke is awesome for increasing and maintaining shoulder mobility (and strength).

If swimming isn’t a viable option for you, then doing the same motion with your arms, while standing, will build the same flexibility. If you do it while holding a small weight (even just 1kg is fine, but feel free to increase if you so wish and safely can) in each hand will build the necessary strength as you go too.

As for why even just 1kg is fine: read on

About that “and strength”, by the way…

Stretching is not everything. Stretching is great, but mobility without strength (in that joint!) is just asking for dislocation.

You don’t have to be built like the Terminator, but you do need to have the structural integrity to move your body and then a little bit more weight than that (or else any extra physical work could be enough to tip you to breaking point) without incurring damage from the strain. So, it needs to not be a strain! See again, the aforementioned resistance exercises.

That said, even very gentle exercise helps too; see for example the impact of walking on osteoporosis:

Living near green spaces linked to higher bone density and lower osteoporosis risk

and…

So you don’t have to run marathons—although you can if you want:

Marathons in Mid- and Later-Life

…to keep your hips and more in good order.

Want to test yourself now?

Check out:

Building & Maintaining Mobility

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Brain Benefits in 3 Months…through walking?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Keeping it Simple

Today’s video (below) is another Big Think production (can you tell that we love their work?). Wendy Suzuki does a wonderful job of breaking down the brain benefits of exercise into three categories, within three minutes.

The first question to ask yourself is: what is your current level of fitness?

Low Fitness

Exercising, even if it’s just going on a walk, 2-3 times a week improves baseline mood state, as well as enhances prefrontal and hippocampal function. These areas of the brain are crucial for complex behaviors like planning and personality development, as well as memory and learning.

Mid Fitness

The suggested regimen is, without surprise, to slightly increase your regular workouts over three months. Whilst you’re already getting the benefits from the low-fitness routine, there is a likelihood that you’ll increase your baseline dopamine and serotonin levels–which, of course, we love! Read more on dopamine here, here, or here.

High Fitness

If you consider yourself in the high fitness bracket then well done, you’re doing an amazing job! Wendy Suzuki doesn’t make many suggestions for you; all she mentions is that there is the possibility of “too much” exercise actually having negative effects on the brain. However, if you’re not competing at an Olympic level, you should be fine.

Fitness and Exercise in General

Of course, fitness and exercise are both very broad terms. We would suggest that you find an exercise routine that you genuinely enjoy–something that is easy to continue over the long term. Try browsing different areas of exercise to see what resonates with you. For instance, Total Fitness After 40 is a great book on all things fitness in the second half of your life. Alternatively, search through our archive for fitness-related material.

Anyway, without further ado, here is today’s video:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Share This Post

-

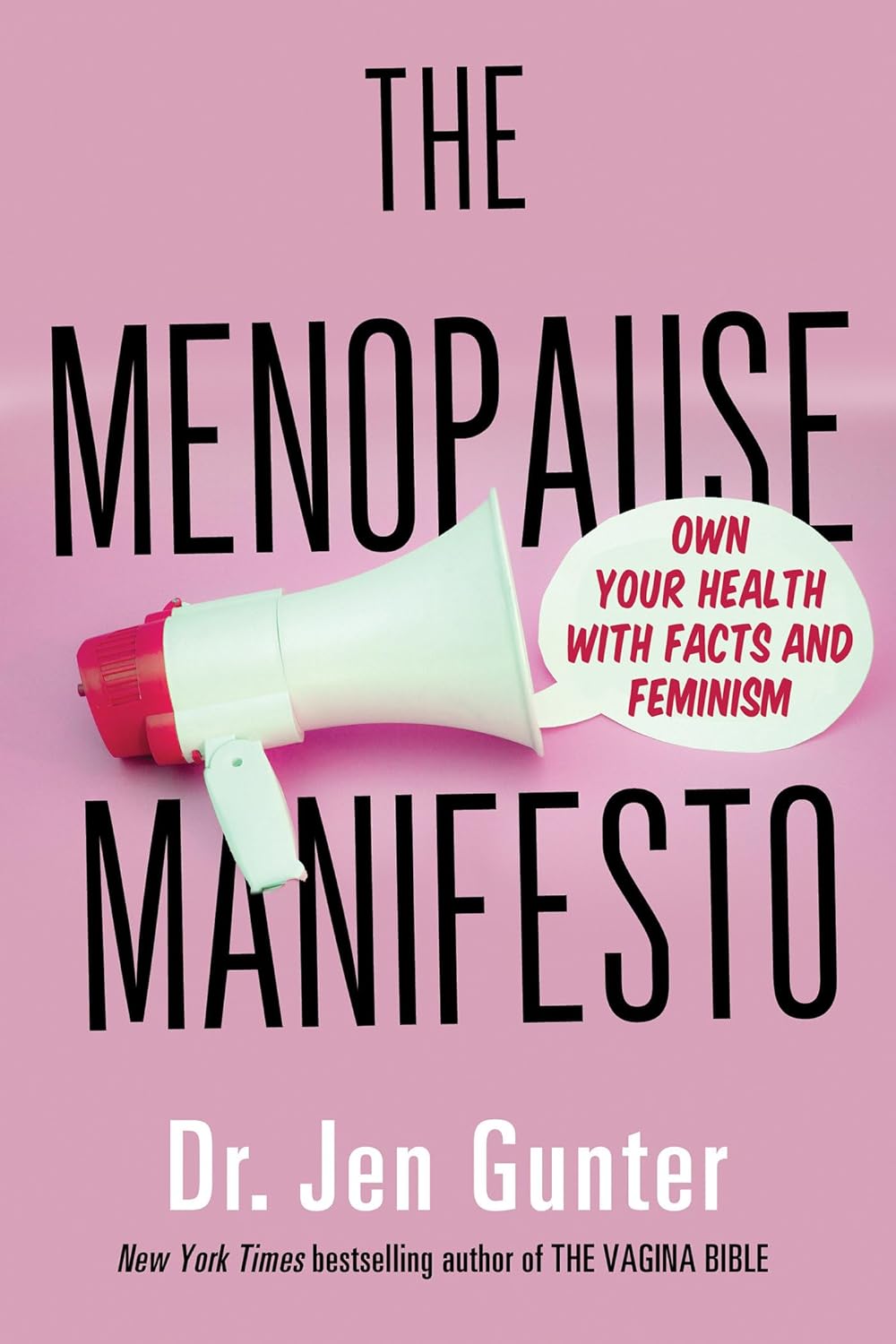

The Menopause Manifesto – by Dr. Jen Gunter

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From the subtitle, you may wonder: with facts and feminism? Is this book about biology or sociology?

And the answer is: both. It’s about biology, principally, but without ignoring the context. We do indeed “live in a society”, and that affects everything from our healthcare options to what is expected of us as women.

So, as a warning: if you dislike science and/or feminism, you won’t like this book.

Dr. Jen Gunter, herself a gynaecologist, is here to arm us with science-based facts, to demystify an important part of life that is commonly glossed over.

She talks first about the what/why/when/how of menopause, and then delivers practical advice. She also talks about the many things we can (and can’t!) usefully do about symptoms we might not want, and how to look after our health overall in the context of menopause. We learn what natural remedies do or don’t work and/or can be actively harmful, and we learn the ins and outs of different hormone therapy options too.

Bottom line: no matter whether you are pre-, peri-, or post-menopausal, this is the no-BS guide you’ve been looking for. Same goes if you’re none of the above but spend any amount of time close to someone who is.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Science of Stretch – by Dr. Leada Malek

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book is part of a “Science of…” series, of which we’ve reviewed some others before (Yoga | HIIT | Pilates), and needless to say, we like them.

You may be wondering: is this just that thing where a brand releases the same content under multiple names to get more sales, and no, it’s not (long-time 10almonds readers will know: if it were, we’d say so!).

While flexibility and mobility are indeed key benefits in yoga and Pilates, they looked into the science of what was going on in yoga asanas and Pilates exercises, stretchy or otherwise, so the stretching element was not nearly so deep as in this book.

In this one, Dr. Malek takes us on a wonderful tour of (relevant) human anatomy and physiology, far deeper than most pop-science books go into when it comes to stretching, so that the reader can really understand every aspect of what’s going on in there.

This is important, because it means busting a lot of myths (instead of busting tendons and ligaments and things), understanding why certain things work and (critically!) why certain things don’t, how certain stretching practices will sabotage our progress, things like that.

It’s also beautifully clearly illustrated! The cover art is a fair representation of the illustrations inside.

Bottom line: if you want to get serious about stretching, this is a top-tier book and you won’t regret it.

Click here to check out Science of Stretching, and learn what you can do and how!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

7 Principles of Becoming a Leader – by Riku Vuorenmaa

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We urge you to overlook the cliché cover art (we don’t know what they were thinking, going for the headless suited torso) because…

This one could be the best investment you make in your career this year! You may be wondering what the titular 7 principles are. We won’t keep you guessing; they are:

- Professional development: personal excellence, productivity, and time management

- Leadership development: mindset and essential leadership skills

- Personal development: your motivation, character, and confidence as a leader

- Career management: plan your career, get promoted and paid well

- Social skills & networking: work and connect with the right people

- Business- & company-understanding: the big picture

- Commitment: make the decision and commit to becoming a great leader

A lot of leadership books repeat the same old fluff that we’ve all read many times before… padded with a lot of lengthy personal anecdotes and generally editorializing fluff. Not so here!

While yes, this book does also cover some foundational things first, it’d be remiss not to. It also covers a whole (much deeper) range of related skills, with down-to-earth, brass tacks advice on putting them into practice.

This is the kind of book you will want to set as a recurring reminder in your phone, to re-read once a year, or whatever schedule seems sensible to you.

There aren’t many books we’d put in that category!

Pick Up Your Copy of the “7 Principles of Becoming a Leader” on Amazon Today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Eat It! – by Jordan Syatt and Michael Vacanti

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One of the biggest challenges we often face when undertaking diet and exercise regimes, is the “regime” part. Day one is inspiring, day two is exciting… Day seventeen when one has a headache and some kitchen appliance just broke and one’s preferred exercise gear is in the wash… Not so much.

Authors Jordan Syatt and Michael Vacanti, therefore, have taken it upon themselves to bring sustainability to us.

Their main premise is simplicity, but simplicity that works. For example:

- Having a daily calorie limit, but being ok with guesstimating

- Weighing regularly, but not worrying about fluctuations (just trends!)

- Eating what you like, but prioritizing some foods over others

- Focusing on resistance training, but accessible exercises that work the whole body, instead of “and then 3 sets of 12 reps of these in 6-4-2 progression to exhaustion of the anterior sternocleidomastoid muscle”

The writing style is simple and clear too, without skimping on the science where science helps explain why something works a certain way.

Bottom line: this one’s for anyone who would like a strong healthy body, without doing the equivalent of a degree in anatomy and physiology along the way.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: