The push for Medicare to cover weight-loss drugs: An explainer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The largest U.S. insurer, Medicare, does not cover weight-loss drugs, making it tougher for older people to get access to promising new medications.

If you cover stories about drug costs in the U.S., it’s important to understand why Medicare’s Part D pharmacy program, which covers people aged 65 and older and people with certain disabilities, doesn’t cover weight-loss drugs today. It’s also important to consider what would happen if Medicare did start covering weight loss drugs. This explainer will give you a brief overview of the issues and then summarize some recent publications the benefits and costs of drugs like semaglutide and tirzepatide.

First, what are these new and newsy weight loss drugs?

Semaglutide is a medication used for both the treatment of type 2 diabetes and for long-term weight management in adults with obesity. It debuted in the United States in 2017 as an injectable diabetes drug called Ozempic, manufactured by Novo Nordisk. It’s part of a class of drugs that mimics the action of glucagon, a substance that the human body makes to aid digestion.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) drugs like semaglutide help prompt the body to release insulin. But they also cause a minor delay in the pace of digestion, helping people feel sated after eating.

That second effect turned Ozempic into a widely used weight-loss drug, even before the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave its okay for this use. Doctors in the United States can prescribe medicines for uses beyond those approved by the FDA. This is known as off-label use.

In writing about her own experience in using the medicine to help her shed 40 pounds, Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus in June noted that Novo Nordisk mentioned the potential for weight loss in its “ubiquitous cable ads (‘Oh-oh-oh, Ozempic!’)”

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists has reported shortages of semaglutide due to demand, leaving some people with diabetes struggling to find supply of the medicine.

Novo Nordisk won Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2021 to market semaglutide as an injectable weight loss drug under the name Wegovy, but with a different dosing regimen than Ozempic. Rival Eli Lilly first won FDA approval of its similar GLP-1 diabetes drug, tirzepatide, in the United States in 2022 and sells it under the brand name Mounjaro.

In November of 2023, Eli Lilly won FDA approval to sell tirzepatide as a weight-loss drug, soon-to-be marketed under the brand name Zepbound. The company said it will set a monthly list price for a month’s supply of the drug at $1,059.87, which the company described as 20% discount to the cost of rival Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy. Wegovy has a list price of $1,349.02, according to the Novo Nordisk website.

Even when their insurance plans officially cover costs for weight loss drugs, consumers may face barriers in seeking that coverage for these drugs. Commercial health plans have in place prior authorization requirements to try to limit coverage of new weight-loss shots to those who qualify for these treatments. The Wegovy shot, for example, is intended for people whose weight reaches a certain benchmark for obesity or who are overweight and have a condition related to excess weight, such as diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol.

State Medicaid programs, meanwhile, have taken approaches that vary by state. For example, the most populous U.S. state, California, provides some coverage to new weight-loss injections through its Medicaid program, but many others, including Texas, the No. 2 state in terms of population, do not, according to an online tool that Novo Nordisk created to help people check on coverage.

Medicare does cover semaglutide for treatment of diabetes, and the insurer reported $3 billion in 2021 spending on the drug under Medicare Part D. Congress last year gave Medicare new tools that might help it try to lower the cost of semaglutide.

Medicare is in the midst of implementing new authority it gained through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 to negotiate with companies about the cost of certain medicines.

This legislation gave Medicare, for the first time, tools to directly negotiate with pharmaceutical companies on the cost of some medicines. Congress tailored this program to spare drug makers from negotiations for the first few years they put new medicines on the market, allowing them to recoup investment in these products.

Why doesn’t Medicare cover weight-loss drugs?

Congress created the Medicare Part D pharmacy program in 2003 to address a gap in coverage that had existed since the creation of Medicare in 1965. The program long covered the costs of drugs administered by doctors and those given in hospitals, but not the kinds of medicines people took on their own, like Wegovy shots.

In 2003, there seemed to be good reasons to leave weight-loss drugs out of the benefit, write Inmaculada Hernandez of the University of California, San Diego, and coauthors in their September 2023 editorial in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, “Medicare Part D Coverage of Anti-obesity Medications: a Call for Forward-Looking Policy Reform.”

When members of Congress worked on the Part D benefit, the drugs available on the market were known to have limited effectiveness and unpleasant side effects. And those members of Congress were aware of how a drug combination called fen-phen, once touted as a weight-loss miracle medicine, turned out in rare cases to cause fatal heart valve damage. In 1997, American Home Products, which later became Wyeth, took its fen-phen product off the market.

But today GLP-1 drugs like semaglutide appear to offer significant benefits, with far less risk and milder side effects, write Hernandez and coauthors.

“Other than budget impact, it is hard to find a reason to justify the historical statutory exclusion of weight loss drugs from coverage other than the stigma of the condition itself,” they write.

What’s happening today that could lead Medicare to start covering weight loss drugs?

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly both have hired lobbyists to try to persuade lawmakers to reverse this stance, according to Senate records. Pro tip: You can use the Senate’s lobbying disclosure database to track this and other issues. Type in the name of the company of interest and then read through the forms.

Some members of Congress already have been trying for years to strike the Medicare Part D restriction on weight-loss drugs. Over the past decade, senators Tom Carper (D-DE) and Bill Cassidy, MD, (R-LA) have repeatedly introduced bills that would do that. They introduced the current version, the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act of 2023, in July. It has the support of 10 other Republican senators and seven Democratic ones, as of Dec. 19. The companion House measure has the support of 41 Democrats and 23 Republicans in that chamber, which has 435 seats.

The influential nonprofit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review conducts in-depth analyses of drugs and medical treatments in the United States. ICER last year recommended passage of a law allowing Medicare Part D to cover weight-loss medications. ICER also called for broader coverage of weight-loss medications in state Medicaid programs. Insurers, including Medicare, consider ICER’s analyses in deciding whether to cover treatments.

While offering these calls for broader coverage as part of a broad assessment of obesity management, ICER also urged companies to reduce the costs of weight-loss medicines.

Most people with obesity can’t achieve sustained weight loss through diet and exercise alone, said David Rind, ICER’s chief medical officer in an August 2022 statement. The development of newer obesity treatments represents the achievement of a long-standing goal of medical research, but prices of these new products must be reasonable to allow broad access to them, he noted.

After an extensive process of reviewing studies, engaging in public debate and processing feedback, ICER concluded that semaglutide for weight loss should have an annual cost of $7,500 to $9,800, based on its potential benefits.

What does academic research say about the benefits and the potential costs of new obesity drugs?

Here are a couple of studies to consider when covering the ongoing story of weight-loss drug costs:

Medicare Part D Coverage of Antiobesity Medications — Challenges and Uncertainty Ahead

Khrysta Baig, Stacie B. Dusetzina, David D. Kim and Ashley A. Leech. New England Journal of Medicine, March 2023

In this Perspective piece, researchers at Vanderbilt University create a series of estimates about how much Medicare may have to spend annually on weight-loss drugs if the program eventually covers these drugs.

These include a high estimate — $268 billion — based on an extreme calculation, one reflecting the potential cost if virtually all people on Medicare who have obesity used semaglutide. In an announcement of the study on the Vanderbilt website, lead author Khrysta Baig described this as a “purely hypothetical scenario,” but one that “ underscores that at current prices, these medications cannot be the only way – or even the main way – we address obesity as a society.”

In a more conservative estimate, Bhaig and coauthors consider a case where only about 10% of those eligible for obesity treatment opted for semaglutide, which would result in $27 billion in new costs.

(To put these numbers in context, consider that the federal government now spends about $145 billion a year on the entire Part D program.)

It’s likely that all people enrolled in Part D would have to pay higher monthly premiums if Medicare were to cover weight-loss injections, Baig and coauthors write.

Baig and coauthors note that the recent ICER review of weight-loss drugs focused on patients younger than the Medicare population. The balance of benefits and risks associated with weight-loss drugs may be less favorable for older people than the younger ones, making it necessary to study further how these drugs work for people aged 65 and older, they write. For example, research has shown older adults with a high blood sugar level called prediabetes are less likely to develop diabetes than younger adults with this condition.

SELECTing Treatments for Cardiovascular Disease — Obesity in the Spotlight

Amit Khera and Tiffany M. Powell-Wiley. New England Journal of Medicine, Dec. 14, 2023

Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients Without Diabetes

A Michael Lincoff, et. al. New England Journal of Medicine, Dec. 14, 2023.

An editorial accompanies the publication of a semaglutide study that drew a lot of coverage in the media. The Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes (SELECT) study was a randomized controlled trial, conducted by Novo Nordisk, which looked at rates of cardiovascular events in people who already had known heart risk and were overweight, but not diabetic. Patients were randomly assigned to receive a once-weekly dose of semaglutide (Wegovy) or a placebo.

In the study, the authors report that of the 8,803 patients who took Wegovy in the trial, 569 (6.5%) had a heart attack or another cardiovascular event, compared with 701 of the 8801 patients (8.0%) in the placebo group. The mean duration of exposure to semaglutide or placebo in the study was 34.2 months.

The study also reports a mean 9.4% reduction in body weight among patients taking Wegovy, while those on placebo had a mean loss of 0.88%.

The findings suggest Wegovy may be a welcome new treatment option for many people who have coronary disease and are overweight, but are not diabetic, write Khera and Powell-Wiley in their editorial.

But the duo, both of whom focus on disease prevention in their research, also call for more focus on the prevention and root causes of obesity and on the use of proven treatment approaches other than medication.

“Socioeconomic, environmental, and psychosocial factors contribute to incident obesity, and therefore equity-focused obesity prevention and treatment efforts must target multiple levels,” they write. “For instance, public policy targeting built environment features that limit healthy behaviors can be coupled with clinical care interventions that provide for social needs and access to treatments like semaglutide.”

Additional information:

The nonprofit KFF, formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation, has done recent reports looking at the potential for expanded coverage of semaglutide:

Medicaid Utilization and Spending on New Drugs Used for Weight Loss, Sept. 8, 2023

What Could New Anti-Obesity Drugs Mean for Medicare? May 18, 2023

And KFF held an Aug. 4 webinar, New Weight Loss Drugs Raise Issues of Coverage, Cost, Access and Equity, for which the recording is posted here.

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Reflexology: What The Science Says

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

How Does Reflexology Work, Really?

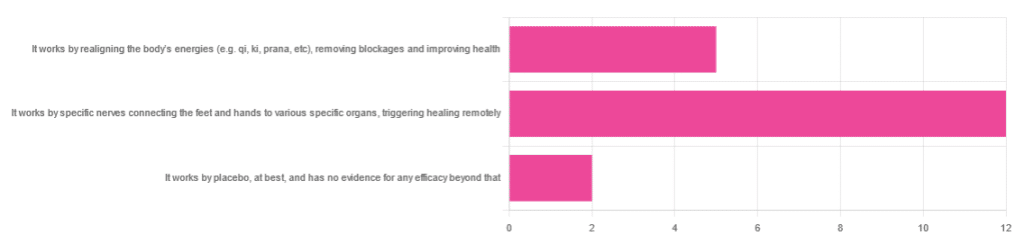

In Wednesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinion of reflexology, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of responses:

- About 63% said “It works by specific nerves connecting the feet and hands to various specific organs, triggering healing remotely”

- About 26% said “It works by realigning the body’s energies (e.g. qi, ki, prana, etc), removing blockages and improving health“

- About 11% said “It works by placebo, at best, and has no evidence for any efficacy beyond that”

So, what does the science say?

It works by realigning the body’s energies (e.g. qi, ki, prana, etc), removing blockages and improving health: True or False?

False, or since we can’t prove a negative: there is no reliable scientific evidence for this.

Further, there is no reliable scientific evidence for the existence of qi, ki, prana, soma, mana, or whatever we want to call it.

To save doubling up, we did discuss this in some more detail, exploring the notion of qi as bioelectrical energy, including a look at some unreliable clinical evidence for it (a study that used shoddy methodology, but it’s important to understand what they did wrong, to watch out for such), when we looked at [the legitimately very healthful practice of] qigong, a couple of weeks ago:

Qigong: A Breath Of Fresh Air?

As for reflexology specifically: in terms of blockages of qi causing disease (and thus being a putative therapeutic mechanism of action for attenuating disease), it’s an interesting hypothesis but in terms of scientific merit, it was pre-emptively supplanted by germ theory and other similarly observable-and-measurable phenomena.

We say “pre-emptively”, because despite orientalist marketing, unless we want to count some ancient pictures of people getting a foot massage and say it is reflexology, there is no record of reflexology being a thing before 1913 (and that was in the US, by a laryngologist working with a spiritualist to produce a book that they published in 1917).

It works by specific nerves connecting the feet and hands to various specific organs, triggering healing remotely: True or False?

False, or since we can’t prove a negative: there is no reliable scientific evidence for this.

A very large independent review of available scientific literature found the current medical consensus on reflexology is that:

- Reflexology is effective for: anxiety (but short lasting), edema, mild insomnia, quality of sleep, and relieving pain (short term: 2–3 hours)

- Reflexology is not effective for: inflammatory bowel disease, fertility treatment, neuropathy and polyneuropathy, acute low back pain, sub acute low back pain, chronic low back pain, radicular pain syndromes (including sciatica), post-operative low back pain, spinal stenosis, spinal fractures, sacroiliitis, spondylolisthesis, complex regional pain syndrome, trigger points / myofascial pain, chronic persistent pain, chronic low back pain, depression, work related injuries of the hip and pelvis

Source: Reflexology – a scientific literary review compilation

(the above is a fascinating read, by the way, and its 50 pages go into a lot more detail than we have room to here)

Now, those items that they found it effective for, looks suspiciously like a short list of things that placebo is often good for, and/or any relaxing activity.

Another review was not so generous:

❝The best evidence available to date does not demonstrate convincingly that reflexology is an effective treatment for any medical condition❞

~ Dr. Edzard Ernst (MD, PhD, FMedSci)

Source: Is reflexology an effective intervention? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials

In short, from the available scientific literature, we can surmise:

- Some researchers have found it to have some usefulness against chiefly psychosomatic conditions

- Other researchers have found the evidence for even that much to be uncompelling

It works by placebo, at best, and has no evidence for any efficacy beyond that: True or False?

Mostly True; of course reflexology runs into similar problems as acupuncture when it comes to testing against placebo:

How Does One Test Acupuncture Against Placebo Anyway?

…but not quite as bad, since it is easier to give a random foot massage while pretending it is a clinical treatment, than to fake putting needles into key locations.

However, as the paper we cited just above (in answer to the previous True/False question) shows, reflexology does not appear to meaningfully outperform placebo—which points to the possibility that it does work by placebo, and is just a placebo treatment on the high end of placebo (because the placebo effect is real, does work, isn’t “nothing”, and some placebos work better than others).

For more on the fascinating science and useful (applicable in daily life!) practicalities of how placebo does work, check out:

How To Leverage Placebo Effect For Yourself

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Is Your Gut Leading You Into Osteoporosis?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Bacterioides Vulgatus & Bone Health

We’ve talked before about the importance of gut health:

And we’ve shared quite some information and resources on osteoporosis:

- The Bare-bones Truth: Osteoporosis Mythbusting

- Osteoporosis Exercises (What To Do, And What To Avoid)

- Vit D + Calcium: Too Much Of A Good Thing?

- Collagen For Bones: We Are Such Stuff As Fish Are Made Of

- Which Osteoporosis Medication, If Any, Is Right For You?

How the two are connected

A recent study looked at Bacterioides vulgatus, a very common gut bacterium, and found that it suppresses the gut’s production of valeric acid, a short-chain fatty acid that enhances bone density:

❝For the study, researchers analyzed the gut bacteria of more than 500 peri- and post-menopausal women in China and further confirmed the link between B. vulgatus and a loss of bone density in a smaller cohort of non-Hispanic White women in the United States.❞

Pop-sci source: Does gut bacteria cause osteoporosis?

The study didn’t stop there, though. They proceeded to test, with a rodent model, the effect of giving them either:

- more B. vulgatus, or

- valeric acid supplements

The results of this were as expected:

- Those who were given more B. vulgatus got worse bone microstructure

- Those who were given valeric acid supplements got stronger bones overall

Study source: Gut microbiota impacts bone via Bacteroides vulgatus-valeric acid-related pathways

Where can I get valeric acid?

We couldn’t find a handy supplement for this, but it is in many foods, including avocados, blueberries, cocoa beans, and an assortment of birds.

Click here to see a more extensive food list (you’ll need to scroll down a little)

Bonus: if you happen to be on HRT in the form of Estradiol valerate (e.g: Progynova), then that “valerate” is an ester of valeric acid, that your body can metabolize and use as such.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Bored of Lunch – by Nathan Anthony

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cooking with a slow cooker is famously easy, but often we settle down on a few recipes and then don’t vary. This book brings a healthy dose of inspiration and variety.

The recipes themselves range from comfort food to fancy entertaining, pasta dishes to risottos, and even what the author categorizes as “fakeaways” (a play on the British English “takeaway”, cf. AmE “takeout”), so indulgent nights in have never been healthier!

For each recipe, you’ll see a nice simple clear layout of all you’d expect (ingredients, method, etc) plus calorie count, so that you can have a rough idea of how much food each meal is.

In terms of dietary restrictions you may have, there’s quite a variety here so it’ll be easy to find things for all needs, and in addition to that, optional substitutions are mostly quite straightforward too.

Bottom line: if you have a slow cooker but have been cooking only the same three things in it for the past ten years, this is the book to liven things up, while staying healthy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Will there soon be a cure for HIV?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, is a chronic health condition that can be fatal without treatment. People with HIV can live healthy lives by taking antiretroviral therapy (ART), but this medication must be taken daily in order to work, and treatment can be costly. Fortunately, researchers believe a cure is possible.

In July, a seventh person was reportedly cured of HIV following a 2015 stem cell transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. The patient stopped taking ART in 2018 and has remained in remission from HIV.

Read on to learn more about HIV, the promise of stem cell transplants, and what other potential cures are on the horizon.

What is HIV?

HIV infects and destroys the immune system’s cells, making people more susceptible to infections. If left untreated, HIV will severely impair the immune system and progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). People living with untreated AIDS typically die within three years.

People with HIV can take ART to help their immune systems recover and to reduce their viral load to an undetectable level, which slows the progression of the disease and prevents them passing the virus to others.

How can stem cell transplants cure HIV?

Several people have been cured of HIV after receiving stem cell transplants to treat leukemia or lymphoma. Stem cells are produced by the spongy tissue located in the center of some bones, and they can turn into new blood cells.

A mutation on the CCR5 gene prevents HIV from infecting new cells and creates resistance to the virus, which is why some HIV-positive people have received stem cells from donors carrying this mutation. (One person was reportedly cured of HIV after receiving stem cells without the CCR5 mutation, but further research is needed to understand how this occurred.)

Despite this promising news, experts warn that stem cell transplants can be fatal, so it’s unlikely this treatment will be available to treat people with HIV unless a stem cell transplant is needed to treat cancer. People with HIV are at an increased risk for blood cancers, such as Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which stem cell transplants can treat.

Additionally, finding compatible donors with the CCR5 mutation who share genetic heritage with patients of color can be challenging, as donors with the mutation are typically white.

What are other potential cures for HIV?

In some rare cases, people who started ART shortly after infection and later stopped treatment have maintained undetectable levels of HIV in their bodies. There have also been some people whose bodies have been able to maintain low viral loads without any ART at all.

Researchers are studying these cases in their search for a cure.

Other treatment options researchers are exploring include:

- Gene therapy: In addition to stem cell transplants, gene therapy for HIV involves removing genes from HIV particles in patients’ bodies to prevent the virus from infecting other cells.

- Immunotherapy: This treatment is typically used in cancer patients to teach their immune systems how to fight off cancer. Research has shown that giving some HIV patients antibodies that target the virus helps them reach undetectable levels of HIV without ART.

- mRNA technology: mRNA, a type of genetic material that helps produce proteins, has been used in vaccines to teach cells how to fight off viruses. Researchers are seeking a way to send mRNA to immune system cells that contain HIV.

When will there be a cure for HIV?

The United Nations and several countries have pledged to end HIV and AIDS by 2030, and a 2023 UNAIDS report affirmed that reaching this goal is possible. However, strategies to meet this goal include HIV prevention and improving access to existing treatment alongside the search for a cure, so we still don’t know when a cure might be available.

How can I find out if I have HIV?

You can get tested for HIV from your primary care provider or at your local health center. You can also purchase an at-home HIV test from a drugstore or online. If your at-home test result is positive, follow up with your health care provider to confirm the diagnosis and get treatment.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Foot Drop!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Interesting about DVT after surgery. A friend recently got diagnosed with foot drop. Could you explain that? Thank you.❞

First, for reference, the article about DVT after surgery was:

DVT Risk Management Beyond The Socks

As for foot drop…

Foot drop is descriptive of the main symptom: the inability to raise the front part of the foot due to localized weakness/paralysis. Hence, if a person with foot drop dangles their feet over the edge of the bed, for example, the affected foot will simply flop down, while the other (if unaffected) can remain in place under its own power. The condition is usually neurological in origin, though there are various more specific causes:

When walking unassisted, this will typically result in a distinctive “steppage gait”, as it’s necessary to lift the foot higher to compensate, or else the toes will scuff along the ground.

There are mobility aids that can return one’s walking to more or less normal, like this example product on Amazon.

Incidentally, the above product will slightly shorten the lifespan of shoes, as it will necessarily pull a little at the front.

There are alternatives that won’t like this example product on Amazon, but this comes with the different problem that it limits the user to stepping flat-footedly, which is not only also not an ideal gait, but also, will serve to allow any muscles down there that were still (partially or fully) functional to atrophy. For this reason, we’d recommend the first product we mentioned over the second one, unless your personal physiotherapist or similar advises otherwise (because they know your situation and we don’t).

Both have their merits, though:

Trends and Technologies in Rehabilitation of Foot Drop: A Systematic Review

Of course, prevention is better than cure, so while some things are unavoidable (especially when it comes to neurological conditions), we can all look after our nerve health as well as possible along the way:

Peripheral Neuropathy: How To Avoid It, Manage It, Treat It

…as well as the very useful:

What Does Lion’s Mane Actually Do, Anyway?

…which this writer personally takes daily and swears by (went from frequent pins-and-needles to no symptoms and have stayed that way, and that’s after many injuries over the years).

If you’d like a more general and less supplements-based approach though, check out:

Steps For Keeping Your Feet A Healthy Foundation

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Make Your Saliva Better For Your Teeth

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A new study has highlighted the importance of lifestyle factors in shaping the oral microbiome—that is to say, how the things we do affect the bacteria that live in our mouths:

Nepali oral microbiomes reflect a gradient of lifestyles from traditional to industrialized

Neither the study title nor the abstract elucidate how, exactly, one impacts the other, but the study itself does (of course) contain that information; we read it, and the short version is:

In terms of the extremes of “most traditional” to “most industrialized”, foragers have the most diverse oral microbiomes (that’s good), and people with an American industrialized lifestyle had the least diverse oral microbiomes (that’s bad). Between the two extremes, we see the gradient promised by the title.

If you do feel like checking it out, Figure 3 in the paper illustrates this nicely.

Also illustrated in the above-linked Figure 3 is oral microbiome composition. In other words (and to oversimplify it rather), how good or bad our mouth bacteria are for us, independent of diversity (so for example, are there more of this or that kind of bacteria).

Once again, there is a gradient, only this time, the ends of it are even more polarized: foragers have a diverse oral microbiome rich with healthy-for-humans bacteria, while people with an American industrialized lifestyle might not have the diversity, but do have a large number of bad-for-humans bacteria.

While many lifestyle factors are dietary or quasi-dietary, e.g. what kinds of foods people eat, whether they drink alcohol, whether they smoke or use gum, etc, many lifestyle factors were examined, including everything from medications and exercise, to things like kitchen location and what fuel is predominantly used, to education and sexual activity and many other things that we don’t have room for here.

You can see how each lifestyle factor stacked up, in Figure 5.

Why it matters

Our oral microbiome affects many aspects of health, including:

- Locally: caries, periodontal diseases, mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and more

- Systemically: gastrointestinal diseases in general, IBS in particular, nervous system diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, endocrine diseases, all manner of immune/autoimmune diseases, and more

Nor are the effects it has mild; oral microbiome health can be a huge factor, statistically, for many of the above. You can see information and data pertaining to all of the above and more, here:

Oral microbiomes: more and more importance in oral cavity and whole body

What to do about it

Take care of your oral microbiome, to help it to take care of you. As well as the above-mentioned lifestyle factors, it’s worth noting that when it comes to oral hygiene, not all oral hygiene products are created equal:

Toothpastes & Mouthwashes: Which Kinds Help, And Which Kinds Harm?

Additionally, you might want to consider gentler options, but if you do, take care to opt for things that science actually backs., rather than things that merely trended on social media.

This writer (hi, it’s me) is particularly excited about the science and use of the miswak stick, which comes from the Saladora persica tree, and has phytochemical properties that (amongst many other health-giving effects) improve the quality of saliva (i.e., improve its pH and microbiome composition). In essence, your own saliva gets biochemically nudged into being the safest, most effective mouthwash.

There’s a lot of science for the use of S. persica, and we’ve discussed it before in more detail than we have room to rehash today, here:

Less Common Oral Hygiene Options

If you’d like to enjoy these benefits (and also have the equivalent of a toothbrush that you can carry with you at all times and does not require water*), then here’s an example product on Amazon 😎

*don’t worry, it won’t feel like dry-brushing your teeth. Remember what we said about what it does to your saliva. Basically, you chomp it once, and your saliva a) increases and b) becomes biological tooth-cleaning fluid. The stick itself is fibrous, so the end of it frays in a way that makes a natural little brush. Each stick is about 5”×¼” and you can carry it in a little carrying case (you’ll get a couple with each pack of miswak sticks), so you can easily use it in, say, the restroom of a restaurant or before your appointment somewhere, just as easily as you could use a toothpick, but with much better results. You may be wondering how long a stick lasts; well, that depends on how much you use it, but in this writer’s experience, each stick lasts about a month maybe, using it at least 2–3 times per day, probably rather more since I use it after each meal/snack and upon awakening.

(the above may read like an ad, but we promise you it’s not sponsored and this writer’s just enthusiastic, and when you read the science, you will be too)

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: