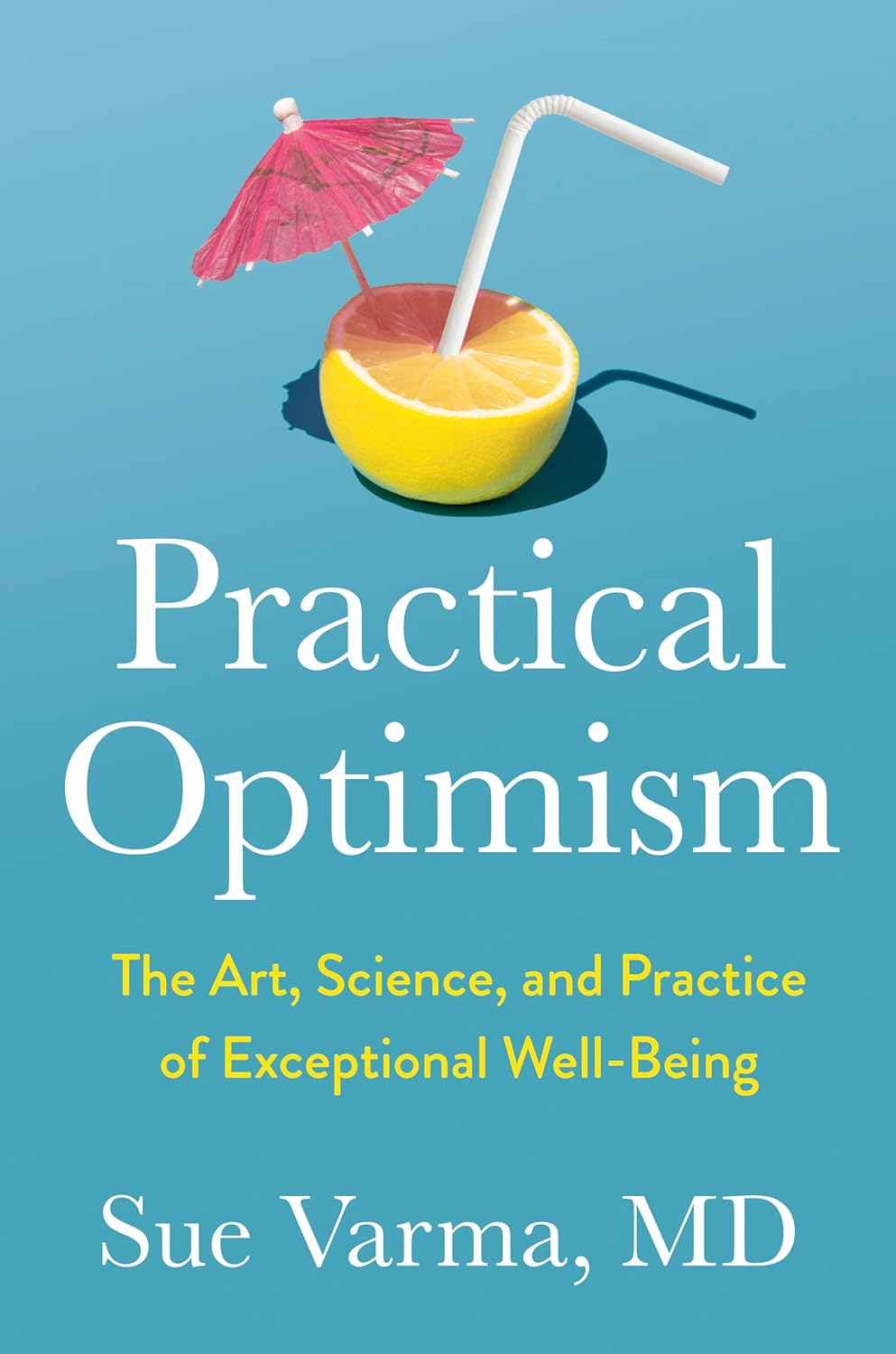

Practical Optimism – by Dr. Sue Varma

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written before about how to get your brain onto a more positive track (without toxic positivity), but there’s a lot more to be said than we can fit into an article, so here’s a whole book packed full with usable advice.

The subtitle claims “the art, science, and practice of…”, but mostly it’s the science of. If there’s art to be found here, then this reviewer missed it, and as for the practice of, well, that’s down to the reader, of course.

However, it is easy to use the contents of this book to translate science into practice without difficulty.

If you’re a fan of acronyms, initialisms, and other mnemonics (such as the rhyming “Name, Claim, Tame, and Reframe”), then you’ll love this book as they come thick and fast throughout, and they contribute to the overall ease of application of the ideas within.

The writing style is conversational but with enough clinical content that one never forgets who is speaking—not in the egotistical way that some authors do, but rather, just, she has a lot of professional experience to share and it shows.

Bottom line: if you’d like to be more optimistic without delving into the delusional, this book can really help a lot with that (in measurable ways, no less!).

Click here to check out Practical Optimism, and brighten up your life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

I’m So Effing Tired – by Dr. Amy Shah

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s easy sometimes to feel like we know more or less what we should be doing… If only we had the energy to get going!

- We know we want a better diet… But we don’t have the time/energy to cook so will go for the quickest option even when it’s not the best?

- We know we should exercise… But feel we just need to crash out on the couch for a bit first?

- We would dearly love to get better sleep… But our responsibilities aren’t facilitating that?

…and so on. Happily, Dr. Amy Shah is here with ways to cut through the Gordian Knot that is this otherwise self-perpetuating cycle of exhaustion.

Most of the book is based around tackling what Dr. Shah calls “the energy trifecta“:

- Hormone levels

- Immune system

- Gut health

You’ll note (perhaps with relief) that none of these things require an initial investment of energy that you don’t have… She’s not asking you to hit the gym at 5am, or magically bludgeon your sleep schedule into its proper place, say.

Instead, what she gives is practical, actionable, easy changes that don’t require much effort, to gently slide us back into the fast lane of actually having energy to do stuff!

In short: if you’ve ever felt like you’d like to implement a lot of very common “best practice” lifestyle advice, but just haven’t had the energy to get going, there’s more value in this handbook than in a thousand motivational pep talks.

Click here to check out “I’m So Effing Tired” and get on a better track of life!

Share This Post

-

How can I stop overthinking everything? A clinical psychologist offers solutions

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As a clinical psychologist, I often have clients say they are having trouble with thoughts “on a loop” in their head, which they find difficult to manage.

While rumination and overthinking are often considered the same thing, they are slightly different (though linked). Rumination is having thoughts on repeat in our minds. This can lead to overthinking – analysing those thoughts without finding solutions or solving the problem.

It’s like a vinyl record playing the same part of the song over and over. With a record, this is usually because of a scratch. Why we overthink is a little more complicated.

We’re on the lookout for threats

Our brains are hardwired to look for threats, to make a plan to address those threats and keep us safe. Those perceived threats may be based on past experiences, or may be the “what ifs” we imagine could happen in the future.

Our “what ifs” are usually negative outcomes. These are what we call “hot thoughts” – they bring up a lot of emotion (particularly sadness, worry or anger), which means we can easily get stuck on those thoughts and keep going over them.

However, because they are about things that have either already happened or might happen in the future (but are not happening now), we cannot fix the problem, so we keep going over the same thoughts.

Who overthinks?

Most people find themselves in situations at one time or another when they overthink.

Some people are more likely to ruminate. People who have had prior challenges or experienced trauma may have come to expect threats and look for them more than people who have not had adversities.

Deep thinkers, people who are prone to anxiety or low mood, and those who are sensitive or feel emotions deeply are also more likely to ruminate and overthink.

We all overthink from time to time, but some people are more prone to rumination.

BĀBI/UnsplashAlso, when we are stressed, our emotions tend to be stronger and last longer, and our thoughts can be less accurate, which means we can get stuck on thoughts more than we would usually.

Being run down or physically unwell can also mean our thoughts are harder to tackle and manage.

Acknowledge your feelings

When thoughts go on repeat, it is helpful to use both emotion-focused and problem-focused strategies.

Being emotion-focused means figuring out how we feel about something and addressing those feelings. For example, we might feel regret, anger or sadness about something that has happened, or worry about something that might happen.

Acknowledging those emotions, using self-care techniques and accessing social support to talk about and manage your feelings will be helpful.

The second part is being problem-focused. Looking at what you would do differently (if the thoughts are about something from your past) and making a plan for dealing with future possibilities your thoughts are raising.

But it is difficult to plan for all eventualities, so this strategy has limited usefulness.

What is more helpful is to make a plan for one or two of the more likely possibilities and accept there may be things that happen you haven’t thought of.

Think about why these thoughts are showing up

Our feelings and experiences are information; it is important to ask what this information is telling you and why these thoughts are showing up now.

For example, university has just started again. Parents of high school leavers might be lying awake at night (which is when rumination and overthinking is common) worrying about their young person.

Think of what the information is telling you.

TheVisualsYouNeed/ShutterstockKnowing how you would respond to some more likely possibilities (such as they will need money, they might be lonely or homesick) might be helpful.

But overthinking is also a sign of a new stage in both your lives, and needing to accept less control over your child’s choices and lives, while wanting the best for them. Recognising this means you can also talk about those feelings with others.

Let the thoughts go

A useful way to manage rumination or overthinking is “change, accept, and let go”.

Challenge and change aspects of your thoughts where you can. For example, the chance that your young person will run out of money and have no food and starve (overthinking tends to lead to your brain coming up with catastrophic outcomes!) is not likely.

You could plan to check in with your child regularly about how they are coping financially and encourage them to access budgeting support from university services.

Your thoughts are just ideas. They are not necessarily true or accurate, but when we overthink and have them on repeat, they can start to feel true because they become familiar. Coming up with a more realistic thought can help stop the loop of the unhelpful thought.

Accepting your emotions and finding ways to manage those (good self-care, social support, communication with those close to you) will also be helpful. As will accepting that life inevitably involves a lack of complete control over outcomes and possibilities life may throw at us. What we do have control over is our reactions and behaviours.

Remember, you have a 100% success rate of getting through challenges up until this point. You might have wanted to do things differently (and can plan to do that) but nevertheless, you coped and got through.

So, the last part is letting go of the need to know exactly how things will turn out, and believing in your ability (and sometimes others’) to cope.

What else can you do?

A stressed out and tired brain will be more likely to overthink, leading to more stress and creating a cycle that can affect your wellbeing.

So it’s important to manage your stress levels by eating and sleeping well, moving your body, doing things you enjoy, seeing people you care about, and doing things that fuel your soul and spirit.

Find ways to manage your stress levels.

antoniodiaz/ShutterstockDistraction – with pleasurable activities and people who bring you joy – can also get your thoughts off repeat.

If you do find overthinking is affecting your life, and your levels of anxiety are rising or your mood is dropping (your sleep, appetite and enjoyment of life and people is being negatively affected), it might be time to talk to someone and get some strategies to manage.

When things become too difficult to manage yourself (or with the help of those close to you), a therapist can provide tools that have been proven to be helpful. Some helpful tools to manage worry and your thoughts can also be found here.

When you find yourself overthinking, think about why you are having “hot thoughts”, acknowledge your feelings and do some future-focused problem solving. But also accept life can be unpredictable and focus on having faith in your ability to cope.

Kirsty Ross, Associate Professor and Senior Clinical Psychologist, Massey University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Tuna vs Catfish – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing tuna to catfish, we picked the tuna.

Why?

Today in “that which is more expensive and/or harder to get is not necessarily healthier”…

Looking at their macros, tuna has more protein and less fat (and overall, less saturated fat, and also less cholesterol).

In the category of vitamins, both are good but tuna distinguishes itself: tuna has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B6, and D, while catfish has more of vitamins B5, B9, B12, E, and K. They are both approximately equal in choline, and as an extra note in tuna’s favor (already winning 6:5), tuna is a very good source of vitamin D, while catfish barely contains any. All in all: a moderate, but convincing, win for tuna.

When it comes to minerals, things are clearer still: tuna has more copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while catfish has more calcium, manganese, and zinc. Oh, and catfish is also higher in one other mineral: sodium, which most people in industrialized countries need less of, on average. So, a 6:3 win for tuna, before we even take into account the sodium content (which makes the win for tuna even stronger).

In short: tuna wins the day in every category!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Farmed Fish vs Wild Caught (It Makes Quite A Difference)

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

When Your Brain’s “Get-Up-And-Go” Has Got Up And Gone…

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sometimes, there are days when the body feels heavy, the brain feels sluggish, and even the smallest tasks feel Herculean.

When these days stack up, this is usually a sign of depression, and needs attention. Unfortunately, when one is in such a state, taking action about it is almost impossible.

Almost, but not quite, as we wrote about previously:

The Mental Health First-Aid You’ll Hopefully Never Need ← this is about as close to true mental health bootstrapping as actually works

Today though, we’re going to assume it’s just an off-day or such. So, what to do about it?

Try turning it off and on again

Sometimes, a reboot is all that’s needed, and if napping is an option, it’s worth considering. However, if you don’t do it right, you can end up groggy and worse off than before, so do check out:

How To Be An Expert Nap-Artist (No More “Sleep Hangovers”!)

If your exhaustion is nevertheless accompanied by stresses that are keeping you from resting, then there’s another “turn it off and on again” process for that:

Fuel in the tank

Our brain is an energy-intensive organ, and cannot run on empty for long. Thus, lacking energy can sometimes simply be a matter of needing to supply some energy. Simple, no? Except, a lot of energy-giving foods can cause a paradoxical slump in energy, so here’s how to avoid that:

Eating For Energy (In Ways That Actually Work)

There are occasions when exhausted, when preparing food seems like too much work. If you’re not in a position to have someone else do it for you, how can you get “most for least” in terms of nutrition for effort?

Many of the above-linked items can help (a bowl of nuts and/or dried fruit is probably not going to break the energy-bank, for instance), but beyond that, there are other considerations too:

How To Eat To Beat Chronic Fatigue (While Chronically Fatigued) ← as the title tells, this is about chronic fatigue, but the advice therein definitely goes for acute fatigue also.

The lights aren’t on

Sometimes it may be that your body is actually fine, but your brain is working in a clunky fashion at best. Assuming there is no more drastic underlying cause for this, a lack of motivation is often as simple as a lack of appropriate dopamine response. When that’s the case…

Lacking Motivation? Science Has The Answer

If, instead, the issue is more serotonin-based than dopamine based, then green places with blue skies are ideal. Depending on geography and season, those things may be in short supply, but the brain is easily tricked with artificial plants and artificial sunlight. Is it as good as a walk in the park on a pleasant summer morning? Probably not, but it’s many times better than nothing, so get those juices flowing:

Neurotransmitter Cheatsheet ← four for the price of one, here!

Schedule time for rest, or your body/brain will schedule it for you

There’s a saying in the field of engineering that “if you don’t schedule time for maintenance, your equipment will schedule it for you”, and the same is true of our body/brain. If you’re struggling to get good quantity, here’s how to at least get good quality:

How To Rest More Efficiently (Yes, Really)

And, importantly,

7 Kinds Of Rest When Sleep Is Not Enough

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is AuDHD? 5 important things to know when someone has both autism and ADHD

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

You may have seen some new ways to describe when someone is autistic and also has attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The terms “AuDHD” or sometimes “AutiADHD” are being used on social media, with people describing what they experience or have seen as clinicians.

It might seem surprising these two conditions can co-occur, as some traits appear to be almost opposite. For example, autistic folks usually have fixed routines and prefer things to stay the same, whereas people with ADHD usually get bored with routines and like spontaneity and novelty.

But these two conditions frequently overlap and the combination of diagnoses can result in some unique needs. Here are five important things to know about AuDHD.

Kosro/Shutterstock 1. Having both wasn’t possible a decade ago

Only in the past decade have autism and ADHD been able to be diagnosed together. Until 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) – the reference used by health workers around the world for definitions of psychological diagnoses – did not allow for ADHD to be diagnosed in an autistic person.

The manual’s fifth edition was the first to allow for both diagnoses in the same person. So, folks diagnosed and treated prior to 2013, as well as much of the research, usually did not consider AuDHD. Instead, children and adults may have been “assigned” to whichever condition seemed most prominent or to be having the greater impact on everyday life.

2. AuDHD is more common than you might think

Around 1% to 4% of the population are autistic.

They can find it difficult to navigate social situations and relationships, prefer consistent routines, find changes overwhelming and repetition soothing. They may have particular sensory sensitivities.

ADHD occurs in around 5–8% of children and adolescents and 2–6% of adults. Characteristics can include difficulties with focusing attention in a flexible way, resulting in procrastination, distraction and disorganisation. People with ADHD can have high levels of activity and impulsivity.

Studies suggest around 40% of those with ADHD also meet diagnostic criteria for autism and vice versa. The co-occurrence of having features or traits of one condition (but not meeting the full diagnostic criteria) when you have the other, is even more common and may be closer to around 80%. So a substantial proportion of those with autism or ADHD who don’t meet full criteria for the other condition, will likely have some traits.

3. Opposing traits can be distressing

Autistic people generally prefer order, while ADHDers often struggle to keep things organised. Autistic people usually prefer to do one thing at a time; people with ADHD are often multitasking and have many things on the go. When someone has both conditions, the conflicting traits can result in an internal struggle.

For example, it can be upsetting when you need your things organised in a particular way but ADHD traits result in difficulty consistently doing this. There can be periods of being organised (when autistic traits lead) followed by periods of disorganisation (when ADHD traits dominate) and feelings of distress at not being able to maintain organisation.

There can be eventual boredom with the same routines or activities, but upset and anxiety when attempting to transition to something new.

Autistic special interests (which are often all-consuming, longstanding and prioritised over social contact), may not last as long in AuDHD, or be more like those seen in ADHD (an intense deep dive into a new interest that can quickly burn out).

Autism can result in quickly being overstimulated by sensory input from the environment such as noises, lighting and smells. ADHD is linked with an understimulated brain, where intense pressure, novelty and excitement can be needed to function optimally.

For some people the conflicting traits may result in a balance where people can find a middle ground (for example, their house appears tidy but the cupboards are a little bit messy).

There isn’t much research yet into the lived experience of this “trait conflict” in AuDHD, but there are clinical observations.

4. Mental health and other difficulties are more frequent

Our research on mental health in children with autism, ADHD or AuDHD shows children with AuDHD have higher levels of mental health difficulites than autism or ADHD alone.

This is a consistent finding with studies showing higher mental health difficulties such as depression and anxiety in AuDHD. There are also more difficulties with day-to-day functioning in AuDHD than either condition alone.

So there is an additive effect in AuDHD of having the executive foundation difficulties found in both autism and ADHD. These difficulties relate to how we plan and organise, pay attention and control impulses. When we struggle with these it can greatly impact daily life.

5. Getting the right treatment is important

ADHD medication treatments are evidence-based and effective. Studies suggest medication treatment for ADHD in autistic people similarly helps improve ADHD symptoms. But ADHD medications won’t reduce autistic traits and other support may be needed.

Non-pharmacological treatments such as psychological or occupational therapy are less researched in AuDHD but likely to be helpful. Evidence-based treatments include psychoeducation and psychological therapy. This might include understanding one’s strengths, how traits can impact the person, and learning what support and adjustments are needed to help them function at their best. Parents and carers also need support.

The combination and order of support will likely depend on the person’s current functioning and particular needs. https://www.youtube.com/embed/pMx1DnSn-eg?wmode=transparent&start=0 ‘Up until recently … if you had one, you couldn’t have the other.’

Do you relate?

Studies suggest people may still not be identified with both conditions when they co-occur. A person in that situation might feel misunderstood or that they can’t fully relate to others with a singular autism and ADHD diagnosis and something else is going on for them.

It is important if you have autism or ADHD that the other is considered, so the right support can be provided.

If only one piece of the puzzle is known, the person will likely have unexplained difficulties despite treatment. If you have autism or ADHD and are unsure if you might have AuDHD consider discussing this with your health professional.

Tamara May, Psychologist and Research Associate in the Department of Paediatrics, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Anti-Aging Myths This Dermatologist Wants You To Stop Believing

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dermatologist Dr. Sam Ellis lays all bare:

Bare-faced lies?

Obviously, we are hearing from a dermatologist here, so the focus is on skin aging specifically. We may well also not want to age our brain, joints, etc, but that’s not what this one is about.

So, without further ado, here are the myths she wants to bust:

- “Medical grade skincare”: the term “medical grade” is a marketing term and does not indicate superior efficacy or better ingredients.

- “Expensive skincare is more effective”: price does not always correlate with effectiveness; some high-end products justify their cost, but many do not.

- “More products = better results”: using too many products can reduce effectiveness and cause irritation; a simple routine with sunscreen and a retinoid is key.

- “Drink more water for better skin”: if you’re dehydrated, then yes, hydrate—but drinking excessive water does not improve skin appearance beyond normal hydration levels.

- “You don’t need anti-aging products until you see signs of aging”: starting skincare early, especially sun protection, helps maintain youthful skin longer.

- “Wrinkles are the first signs of aging”: hyperpigmentation and sagging are often more significant early indicators of aging than wrinkles.

- “Skincare is all you need for anti-aging”: by “skincare” here she means creams, lotions, tonics, etc, and recommends other treatments such as laser treatment and even Botox*.

- “Non-prescription retinoids are a waste of time”: over-the-counter retinoids like retinol and retinal can still be effective alternatives to prescription retinoids.

- “You must use retinoids every night”: retinoids are effective even when used a few times per week, depending on individual tolerance.

*We’re not convinced about the Botox; we’ll have to do a deep-dive research review one of these days!

For more on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Retinoids: Retinol vs Retinal vs Retinoic Acid vs..?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: