Our blood-brain barrier stops bugs and toxins getting to our brain. Here’s how it works

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our brain is an extremely complex and delicate organ. Our body fiercely protects it by holding onto things that help it and keeping harmful things out, such as bugs that can cause infection and toxins.

It does that though a protective layer called the blood-brain barrier. Here’s how it works, and what it means for drug design.

First, let’s look at the circulatory system

Adults have roughly 30 trillion cells in their body. Every cell needs a variety of nutrients and oxygen, and they produce waste, which needs to be taken away.

Our circulatory system provides this service, delivering nutrients and removing waste.

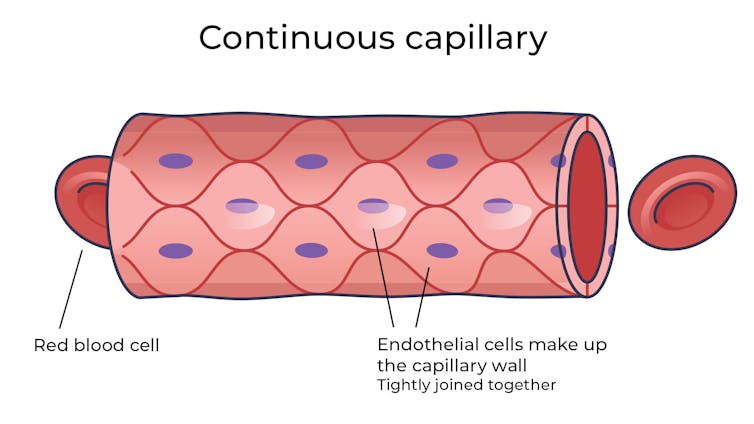

Where the circulatory system meets your cells, it branches down to tiny tubes called capillaries. These tiny tubes, about one-tenth the width of a human hair, are also made of cells.

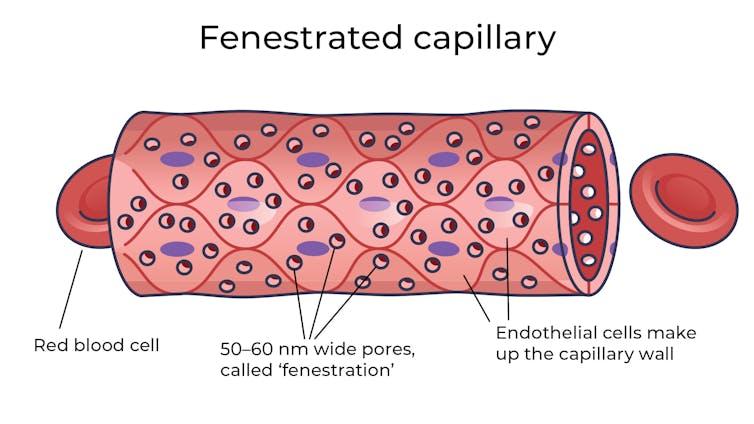

But in most capillaries, there are some special features (known as fenestrations) that allow relatively free exchange of nutrients and waste between the blood and the cells of your tissues.

It’s kind of like pizza delivery

One way to think about the way the circulation works is like a pizza delivery person in a big city. On the really big roads (vessels) there are walls and you can’t walk up to the door of the house and pass someone the pizza.

But once you get down to the little suburban streets (capillaries), the design of the streets means you can stop, get off your scooter and walk up to the door to deliver the pizza (nutrients).

We often think of the brain as a spongy mass without much blood in it. In reality, the average brain has about 600 kilometres of blood vessels.

The difference between the capillaries in most of the brain and those elsewhere is that these capillaries are made of specialised cells that are very tightly joined together and limit the free exchange of anything dissolved in your blood. These are sometimes called continuous capillaries.

This is the blood brain barrier. It’s not so much a bag around your brain stopping things from getting in and out but more like walls on all the streets, even the very small ones.

The only way pizza can get in is through special slots and these are just the right shape for the pizza box.

The blood brain barrier is set up so there are specialised transporters (like pizza box slots) for all the required nutrients. So mostly, the only things that can get in are things that there are transporters for or things that look very similar (on a molecular scale).

The analogy does fall down a little bit because the pizza box slot applies to nutrients that dissolve in water. Things that are highly soluble in fat can often bypass the slots in the wall.

Why do we have a blood-brain barrier?

The blood brain barrier is thought to exist for a few reasons.

First, it protects the brain from toxins you might eat (think chemicals that plants make) and viruses that often can infect the rest of your body but usually don’t make it to your brain.

It also provides protection by tightly regulating the movement of nutrients and waste in and out, providing a more stable environment than in the rest of the body.

Lastly, it serves to regulate passage of immune cells, preventing unnecessary inflammation which could damage cells in the brain.

What it means for medicines

One consequence of this tight regulation across the blood brain barrier is that if you want a medicine that gets to the brain, you need to consider how it will get in.

There are a few approaches. Highly fat-soluble molecules can often pass into the brain, so you might design your drug so it is a bit greasy.

Another option is to link your medicine to another molecule that is normally taken up into the brain so it can hitch a ride, or a “pro-drug”, which looks like a molecule that is normally transported.

Using it to our advantage

You can also take advantage of the blood brain barrier.

Opioids used for pain relief often cause constipation. They do this because their target (opioid receptors) are also present in the nervous system of the intestines, where they act to slow movement of the intestinal contents.

Imodium (Loperamide), which is used to treat diarrhoea, is actually an opioid, but it has been specifically designed so it can’t cross the blood brain barrier.

This design means it can act on opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, slowing down the movement of contents, but does not act on brain opioid receptors.

In contrast to Imodium, Ozempic and Victoza (originally designed for type 2 diabetes, but now popular for weight-loss) both have a long fat attached, to improve the length of time they stay in the body.

A consequence of having this long fat attached is that they can cross the blood-brain barrier, where they act to suppress appetite. This is part of the reason they are so effective as weight-loss drugs.

So while the blood brain barrier is important for protecting the brain it presents both a challenge and an opportunity for development of new medicines.

Sebastian Furness, ARC Future Fellow, School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Almond Butter vs Cashew Butter – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing almond butter to cashew butter, we picked the almond.

Why?

They’re both good! But, our inherent pro-almond bias notwithstanding, the almond butter does have a slightly better spread of nutrients.

In terms of macros, almond butter has more protein while cashew butter has more carbs, and of their fats, they’re broadly healthy in both cases, but almond butter does have less saturated fat.

In the category of vitamins, both are good sources of vitamin E, but almond butter has about 4x more. The rest of the vitamins they both contain aren’t too dissimilar, aside from some different weightings of various different B-vitamins, that pretty much balance out across the two nut butters. The only noteworthy point in cashew butter’s favor here is that it is a good source of vitamin K, which almond butter doesn’t have.

When it comes to minerals, both are good sources of lots of minerals, but most significantly, almond butter has a lot more calcium and quite a bit more potassium. In contrast, cashew butter has more selenium.

In short, they’re both great, but almond butter has more relative points in its favor than cashew butter.

Here are the two we depicted today, by the way, in case you’d like to try them:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Black Forest Chia Pudding

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This pudding tastes so decadent, it’s hard to believe it’s so healthy, but it is! Not only is it delicious, it’s also packed with nutrients including protein, carbohydrates, healthy fats (including omega-3s), fiber, vitamins, minerals, and assorted antioxidant polyphenols. Perfect dessert or breakfast!

You will need

- 1½ cups pitted fresh or thawed-from-frozen cherries

- ½ cup mashed banana

- 3 tbsp unsweetened cocoa powder

- 2 tbsp chia seeds, ground

- Optional: 2 pitted dates, soaked in hot water for 10 minutes and then drained (include these if you prefer a sweeter pudding)

- Garnish: a few almonds, and/or berries, and/or cherries and/or cacao nibs

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Blend the ingredients except for the chia seeds and the garnish, with ½ cup of water, until completely smooth

2) Divide into two small bowls or glass jars

3) Add 1 tbsp ground chia seeds to each, and stir until evenly distributed

4) Add the garnish and refrigerate overnight or at least for some hours. There’s plenty of wiggle-room here, so make it at your convenience and serve at your leisure.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Cherries’ Very Healthy Wealth Of Benefits!

- If You’re Not Taking Chia, You’re Missing Out

- Cacao vs Carob – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

What’s the difference between wholemeal and wholegrain bread? Not a whole lot

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you head to the shops to buy bread, you’ll face a variety of different options.

But it can be hard to work out the difference between all the types on sale.

For instance, you might have a vague idea that wholemeal or wholegrain bread is healthy. But what’s the difference?

Here’s what we know and what this means for shoppers in Australia and New Zealand.

Phish Photography/Shutterstock Let’s start with wholemeal bread

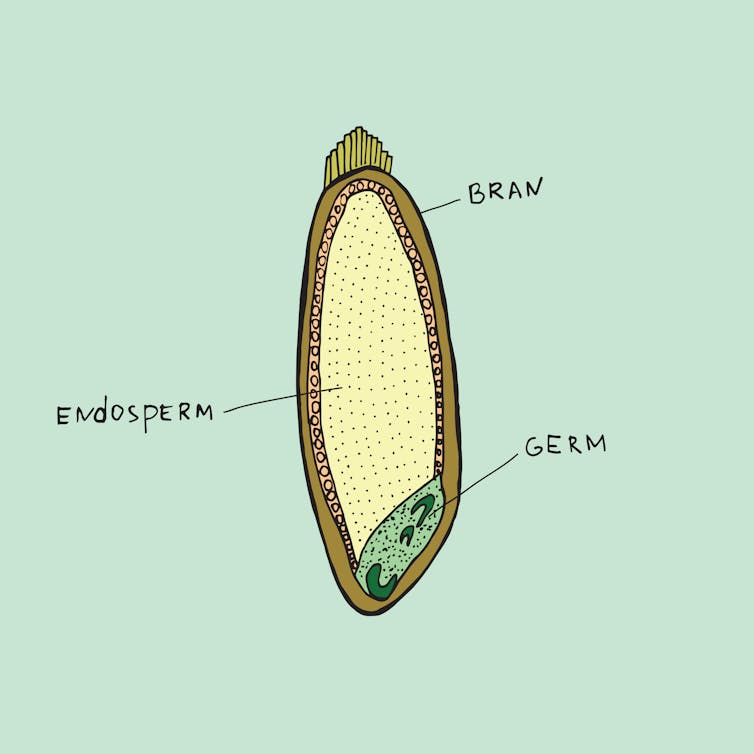

According to Australian and New Zealand food standards, wholemeal bread is made from flour containing all parts of the original grain (endosperm, germ and bran) in their original proportions.

Because it contains all parts of the grain, wholemeal bread is typically darker in colour and slightly more brown than white bread, which is made using only the endosperm.

Wholemeal flour is made from all parts of the grain. Rerikh/Shutterstock How about wholegrain bread?

Australian and New Zealand food standards define wholegrain bread as something that contains either the intact grain (for instance, visible grains) or is made from processed grains (flour) where all the parts of the grain are present in their original proportions.

That last part may sound familiar. That’s because wholegrain is an umbrella term that encompasses both bread made with intact grains and bread made with wholemeal flour. In other words, wholemeal bread is a type of wholegrain bread, just like an apple is a type of fruit.

Don’t be confused by labels such as “with added grains”, “grainy” or “multigrain”. Australian and New Zealand food standards don’t define these so manufacturers can legally add a small amount of intact grains to white bread to make the product appear healthier. This doesn’t necessarily make these products wholegrain breads.

So unless a product is specifically called wholegrain bread, wholemeal bread or indicates it “contains whole grain”, it is likely to be made from more refined ingredients.

Which one’s healthier?

So when thinking about which bread to choose, both wholemeal and wholegrain breads are rich in beneficial compounds including nutrients and fibre, more so than breads made from further-refined flour, such as white bread.

The presence of these compounds is what makes eating wholegrains (including wholemeal bread) beneficial for our overall health. Research has also shown eating wholegrains helps reduce the risk of common chronic diseases, such as heart disease.

The table below gives us a closer look at the nutritional composition of these breads, and shows some slight differences.

Wholegrain bread is slightly higher in fibre, protein, niacin (vitamin B3), iron, zinc, phosphorus and magnesium than wholemeal bread. But wholegrain bread is lower in carbohydrates, thiamin (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9).

However the differences are relatively small when considering how these contribute to your overall dietary intake.

Which one should I buy?

Next time you’re shopping, look for a wholegrain bread (one made from wholemeal flour that has intact grains and seeds throughout) as your number one choice for fibre and protein, and to support overall health.

If you can’t find wholegrain bread, wholemeal bread comes in a very close second.

Wholegrain and wholemeal bread tend to cost the same, but both tend to be more expensive than white bread.

Margaret Murray, Senior Lecturer, Nutrition, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What Are The “Bright Lines” Of Bright Line Eating?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is Dr. Susan Thompson. She’s a cognitive neuroscientist who has turned her hand to helping people to lose weight and maintain it at a lower level, using psychology to combat overeating. She is the founder of “Bright Line Eating”.

We’ll say up front: it’s not without some controversy, and we’ll address that as we go, but we do believe the ideas are worth examining, and then we can apply them or not as befits our personal lives.

What does she want us to know?

Bright Line Eating’s general goal

Dr. Thompson’s mission statement is to help people be “happy, thin, and free”.

You will note that this presupposes thinness as desirable, and presumes it to be healthy, which frankly, it’s not for everyone. Indeed, for people over a certain age, having a BMI that’s slightly into the “overweight” category is a protective factor against mortality (which is partly a flaw of the BMI system, but is an interesting observation nonetheless):

When BMI Doesn’t Quite Measure Up

Nevertheless, Dr. Thompson makes the case for the three items (happy, thin, free) coming together, which means that any miserable or unhealthy thinness is not what the approach is valuing, since it is important for “thin” to be bookended by “happy” and “free”.

What are these “bright lines”?

Bright Line Eating comes with 4 rules:

- No flour (no, not even wholegrain flour; enjoy whole grains themselves yes, but flour, no)

- No sugar (and as a tag-along to this, no alcohol) (sugars naturally found in whole foods, e.g. the sugar in an apple if eating an apple, is ok, but other kinds are not, e.g. foods with apple juice concentrate as a sweetener; no “natural raw cane sugar” etc is not allowed either; despite the name, it certainly doesn’t grow on the plant like that)

- No snacking, just three meals per day(not even eating the ingredients while cooking—which also means no taste-testing while cooking)

- Weigh all your food (have fun in restaurants—but more seriously, the idea here is to plan each day’s 3 meals to deliver a healthy macronutrient balance and a capped calorie total).

You may be thinking: “that sounds dismal, and not at all bright and cheerful, and certainly not happy and free”

The name comes from the idea that these rules are lines that one does not cross. They are “bright” lines because they should be observed with a bright and cheery demeanour, for they are the rules that, Dr. Thompson says, will make you “happy, thin, and free”.

You will note that this is completely in opposition to the expert opinion we hosted last week:

What Flexible Dieting Really Means

Dr. Thompson’s position on “freedom” is that Bright Line Eating is “very structured and takes a liberating stand against moderation”

Which may sound a bit of an oxymoron—is she really saying that we are going to be made free from freedom?

But there is some logic to it, and it’s about the freedom from having to make many food-related decisions at times when we’re likely to make bad ones:

Where does the psychology come in?

Dr. Thompson’s position is that willpower is a finite, expendable resource, and therefore we should use it judiciously.

So, much like Steve Jobs famously wore the same clothes every day because he had enough decisions to make later in the day that he didn’t want unnecessary extra decisions to make… Bright Line Eating proposes that we make certain clear decisions up front about our eating, so then we don’t have to make so many decisions (and potentially the wrong decisions) later when hungry.

You may be wondering: ”doesn’t sticking to what we decided still require willpower?”

And… Potentially. But the key here is shutting down self-negotiation.

Without clear lines drawn in advance, one must decide, “shall I have this cake or not?”, perhaps reflecting on the pros and cons, the context of the situation, the kind of day we’re having, how hungry we are, what else there is available to eat, what else we have eaten already, etc etc.

In short, there are lots of opportunities to rationalize the decision to eat the cake.

With clear lines drawn in advance, one must decide, “shall I have this cake or not?” and the answer is “no”.

So while sticking to that pre-decided “no” still may require some willpower, it no longer comes with a slew of tempting opportunities to rationalize a “yes”.

Which means a much greater success rate, both in adherence and outcomes. Here’s an 8-week interventional study and 2-year follow-up:

Bright Line Eating | Research Publications

Counterpoint: pick your own “bright lines”

Dr. Thompson is very keen on her 4 rules that have worked for her and many people, but she recognizes that they may not be a perfect fit for everyone.

So, it is possible to pick and choose our own “bright lines”; it is after all a dietary approach, not a religion. Here’s her response to someone who adopted the first 3 rules, but not the 4th:

Bright Lines as Guidelines for Weight Loss

The most important thing for Bright Line Eating, therefore, is perhaps the action of making clear decisions in advance and sticking to them, rather than seat-of-the-pantsing our diet, and with it, our health.

Want to know more from Dr. Thompson?

You might like her book, which we reviewed a while ago:

Bright Line Eating – by Dr. Susan Peirce Thompson

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

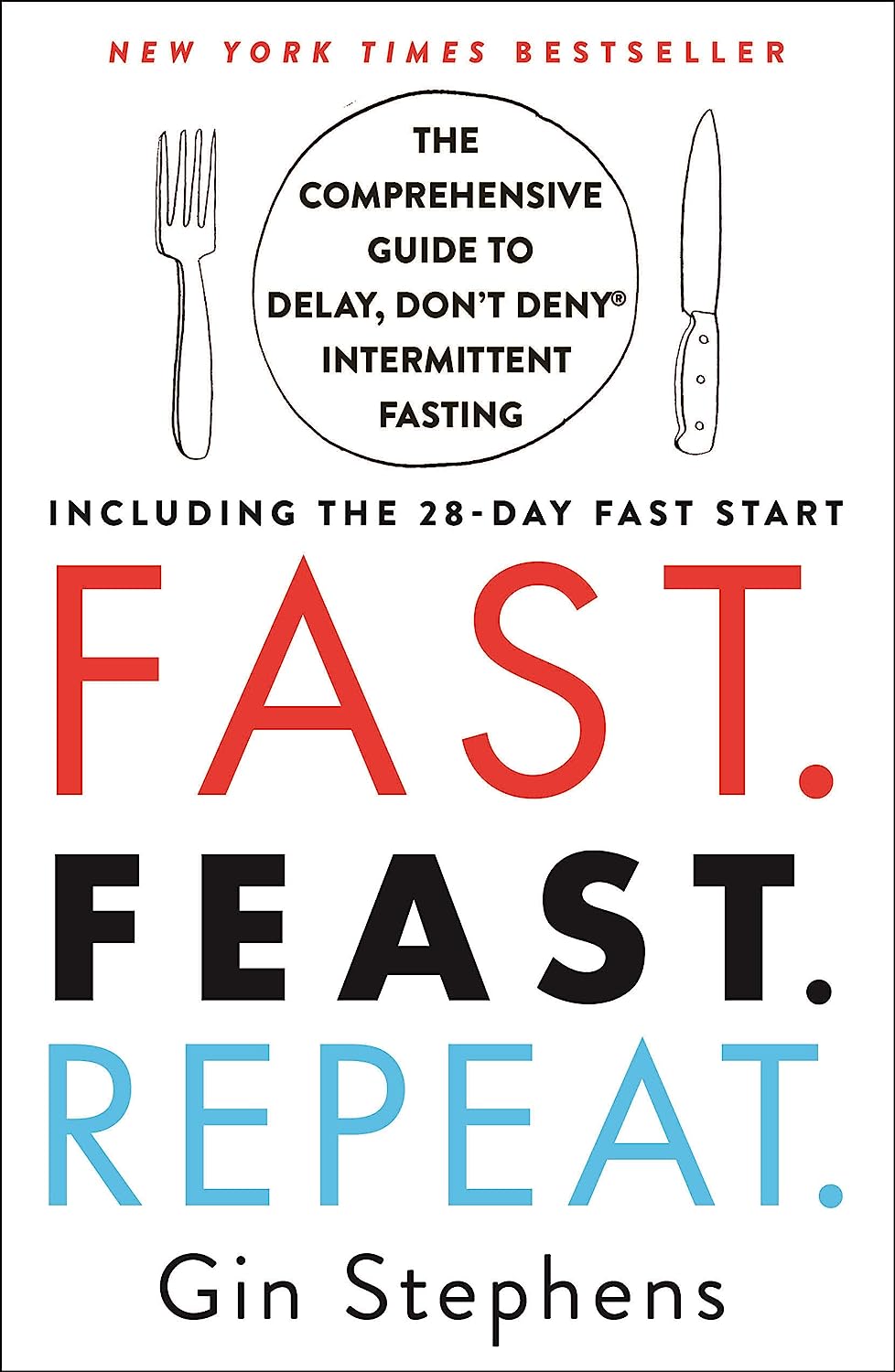

Fast. Feast. Repeat – by Dr. Gin Stephens

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed intermittent fasting books before, so what makes this one different?

The title “Fast. Feast. Repeat.” doesn’t give much away; after all, we already know that that’s what intermittent fasting is.

After taking the reader though the basics of how intermittent fasting works and what it does for the body, much of the rest of the book is given over to improvements.

That’s what the real strength of this book is: ways to make intermittent fasting more efficient, including how to avoid plateaus. After all, sometimes it can seem like the only way to push further with intermittent fasting is to restrict the eating window further. Not so!

Instead, Dr. Stephens gives us ways to keep confusing our metabolism (in a good way) if, for example, we had a weight loss goal we haven’t met yet.

Best of all, this comes without actually having to eat less.

Bottom line: if you want to be in good physical health, and/but also believe that life is for living and you enjoy eating food, then this book can resolve that age-old dilemma!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

People on Ozempic may have fewer heart attacks, strokes and addictions – but more nausea, vomiting and stomach pain

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Ozempic and Wegovy are increasingly available in Australia and worldwide to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity.

The dramatic effects of these drugs, known as GLP-1s, on weight loss have sparked huge public interest in this new treatment option.

However, the risks and benefits are still being actively studied.

In a new study in Nature Medicine, researchers from the United States reviewed health data from about 2.4 million people who have type 2 diabetes, including around 216,000 people who used a GLP-1 drug, between 2017 and 2023.

The researchers compared a range of health outcomes when GLP-1s were added to a person’s treatment plan, versus managing their diabetes in other ways, often using glucose-lowering medications.

Overall, they found people who used GLP-1s were less likely to experience 42 health conditions or adverse health events – but more likely to face 19 others.

myskin/Shutterstock What conditions were less common?

Cardiometabolic conditions

GLP-1 use was associated with fewer serious cardiovascular and coagulation disorders. This includes deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, cardiac arrest, heart failure and myocardial infarction.

Neurological and psychiatric conditions

GLP-1 use was associated with fewer reported substance use disorders or addictions, psychotic disorders and seizures.

Infectious conditions

GLP-1 use was associated with fewer bacterial infections and pneumonia.

What conditions were more common?

Gastrointestinal conditions

Consistent with prior studies, GLP-1 use was associated with gastrointestinal conditions such as nausea, vomiting, gastritis, diverticulitis and abdominal pain.

Other adverse effects

Increased risks were seen for conditions such as low blood pressure, syncope (fainting) and arthritis.

People who took Ozempic were more likely to experience stomach upsets than those who used other type 2 diabetes treatments. Douglas Cliff/Shutterstock How robust is this study?

The study used a large and reputable dataset from the US Department of Veterans Affairs. It’s an observational study, meaning the researchers tracked health outcomes over time without changing anyone’s treatment plan.

A strength of the study is it captures data from more than 2.4 million people across more than six years. This is much longer than what is typically feasible in an intervention study.

Observational studies like this are also thought to be more reflective of the “real world”, because participants aren’t asked to follow instructions to change their behaviour in unnatural or forced ways, as they are in intervention studies.

However, this study cannot say for sure that GLP-1 use was the cause of the change in risk of different health outcomes. Such conclusions can only be confidently made from tightly controlled intervention studies, where researchers actively change or control the treatment or behaviour.

The authors note the data used in this study comes from predominantly older, white men so the findings may not apply to other groups.

Also, the large number of participants means that even very small effects can be detected, but they might not actually make a real difference in overall population health.

Observational studies track outcomes over time, but can’t say what caused the changes. Jacob Lund/Shutterstock Other possible reasons for these links

Beyond the effect of GLP-1 in the body, other factors may explain some of the findings in this study. For example, it’s possible that:

- people who used GLP-1 could be more informed about treatment options and more motivated to manage their own health

- people who used GLP-1 may have received it because their health-care team were motivated to offer the latest treatment options, which could lead to better care in other areas that impact the risk of various health outcomes

- people who used GLP-1 may have been able to do so because they lived in metropolitan centres and could afford the medication, as well as other health-promoting services and products, such as gyms, mental health care, or healthy food delivery services.

Did the authors have any conflicts of interest?

Two of the study’s authors declared they were “uncompensated consultants” for Pfizer, a global pharmaceutical company known for developing a wide range of medicines and vaccines. While Pfizer does not currently make readily available GLP-1s such as Ozempic or Wegovy, they are attempting to develop their own GLP-1s, so may benefit from greater demand for these drugs.

This research was funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, a government agency that provides a wide range of services to military veterans.

No other competing interests were reported.

Diabetes vs weight-loss treatments

Overall, this study shows people with type 2 diabetes using GLP-1 medication generally have more positive health outcomes than negative health outcomes.

However, the study didn’t include people without type 2 diabetes. More research is needed to understand the effects of these medications in people without diabetes who are using them for other reasons, including weight loss.

While the findings highlight the therapeutic benefits of GLP-1 medications, they also raise important questions about how to manage the potential risks for those who choose to use this medication.

The findings of this study can help many people, including:

- policymakers looking at ways to make GLP-1 medications more widely available for people with various health conditions

- health professionals who have regular discussions with patients considering GLP-1 use

- individuals considering whether a GLP-1 medication is right for them.

Lauren Ball, Professor of Community Health and Wellbeing, The University of Queensland and Emily Burch, Accredited Practising Dietitian and Lecturer, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: