Lobster vs Crab – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing lobster to crab, we picked the crab.

Why?

Generally speaking, most seafood is healthy in moderation (assuming it’s well-prepared, not poisonous, and you don’t have an allergy), and for most people, these two sea creatures are indeed considered a reasonable part of a healthy balanced diet.

In terms of macros, they’re comparable in protein, and technically crab has about 2x the fat, but in both cases it’s next to nothing, so 2x almost nothing is still almost nothing. And, if we break down the lipids profiles, crab has a sufficiently smaller percentage of saturated fat (compared to monounsaturated and polyunsaturated), that crab actually has less saturated fat than lobster. In balance, the category of macros is either a tie or a slight win for crab, depending on your personal priorities.

When it comes to vitamins, crab wins easily with more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and C, in most cases by considerable margins (we’re talking multiples of what lobster has). Lobster, meanwhile, has more of vitamin B3 (tiny margin) and vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid, as in, the vitamin that’s in basically everything edible, and thus almost impossible to be deficient in unless literally starving).

The minerals scene is more balanced; lobster has more calcium, copper, manganese, and selenium, while crab has more iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc. The margins are comparable from one creature to another, so all in all the 4:5 score means a modest win for crab.

Both of these creatures are good sources of omega-3 fatty acids, but crab is better.

Lobster and crab are both somewhat high in cholesterol, but crab is the relatively lower of the two.

In short: for most people most of the time, both are fine to enjoy in moderation, but if picking one, crab is the healthier by most metrics.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Shrimp vs Caviar – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What you need to know about H5N1 bird flu

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

On May 30, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that a Michigan dairy worker tested positive for H5N1 bird flu. It was the fourth person to test positive for H5N1 in the United States, following another recent case in Michigan, an April case in Texas, and an initial case in Colorado in 2022.

H5N1 bird flu has been spreading among bird species in the U.S. since 2021, killing millions of wild birds and poultry. In late March 2024, H5N1 bird flu was found in cows for the first time, causing an outbreak in dairy cows across several states.

U.S. public health officials and researchers are particularly concerned about this outbreak because the virus has infected cows and other mammals and has spread from a cow to a human for the first time.

This bird flu strain has shown to not only make wild mammals, including marine mammals and bears, very sick but to also cause high rates of death among species, says Jane Sykes, professor of small animal medicine at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine.

“And now that it has been found in cattle, [it] raises particular concern for spread to all the animal species, including people,” adds Sykes.

Even though the risk for human infection is low and there has never been human-to-human transmission of H5N1, there are several actions you can take to stay protected. Read on to learn more about H5N1 bird flu and the current outbreak.

What is H5N1?

H5N1 is a type of influenza virus that most commonly affects birds, causing them severe respiratory illness and death.

The H5N1 strain first emerged in China in the 1990s, and it has continued to spread around the world since then. In 1997, the virus spread from animals to humans in Hong Kong for the first time, infecting 18 people, six of whom died.

Since 2020, the H5N1 strain has caused “an unprecedented number of deaths in wild birds and poultry in many countries,” according to the World Health Organization.

Even though bird flu is rare in humans, an H5N1 infection can cause mild to severe illness and can be fatal in some cases. It can cause eye infection, upper respiratory symptoms, and pneumonia.

What do we know about the 2024 human cases of H5N1 in the U.S.?

The Michigan worker who tested positive for H5N1 in late May is a dairy worker who was exposed to infected livestock. They were the first to experience respiratory symptoms—including a cough without a fever—during the current outbreak. They were given an antiviral and the CDC says their symptoms are resolving.

The Michigan farm worker who tested positive earlier in May only experienced eye-related symptoms and has already recovered. And the dairy worker who tested positive for the virus in Texas in April only experienced eye redness as well, was treated with an antiviral medication for the flu, and is recovering.

Is H5N1 bird flu in the milk we consume?

The Food and Drug Administration has found traces of H5N1 bird flu virus in raw or unpasteurized milk. However, pasteurized milk is safe to drink.

Pasteurization, the process of heating milk to high temperatures to kill harmful bacteria (which the majority of commercially sold milk goes through), deactivates the virus. In 20 percent of pasteurized milk samples, the FDA found small, inactive (not live nor infectious) traces of the virus, but these fragments do not make pasteurized milk dangerous.

In a recent Infectious Diseases Society of America briefing, Dr. Maximo Brito, a professor at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, said that it’s important for people to avoid “drinking unpasteurized or raw milk [because] there are other diseases, not only influenza, that could be transmitted by drinking unpasteurized milk.”

What can I do to prevent bird flu?

While the risk of H5N1 infection in humans is low, people with exposure to infected animals (like farmworkers) are most at risk. But there are several actions you can take to stay protected.

One of the most important things, according to Sykes, is taking the usual precautions we’ve taken with COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses, including frequent handwashing, especially before eating.

“Handwashing and mask-wearing [are important], just as we learned from the pandemic,” Sykes adds. “And it’s not wearing a mask at all times, but thinking about high-risk situations, like when you’re indoors in a crowded environment, where transmission of respiratory viruses is much more likely to occur.”

There are other steps you can take to prevent H5N1, according to the CDC:

- Avoid direct contact with sick or dead animals, including wild birds and poultry.

- Don’t touch surfaces that may have been contaminated with animal poop, saliva, or mucus.

- Cook poultry and eggs to an internal temperature of 165 degrees Fahrenheit to kill any bacteria or virus, including H5N1. Generally, avoid eating undercooked food.

- Avoid consuming unpasteurized or raw milk or products like cheeses made with raw milk.

- Avoid eating uncooked or undercooked food.

- Poultry and livestock farmers and workers and bird flock owners should wear masks and other personal protective equipment “when in direct or close physical contact with sick birds, livestock, or other animals; carcasses; feces; litter; raw milk; or surfaces and water that might be contaminated with animal excretions from potentially or confirmed infected birds, livestock, or other animals.” (The CDC has more recommendations for this population here.)

Is there a vaccine for H5N1?

The CDC said there are two candidate H5N1 vaccines ready to be made and distributed in case the virus starts to spread from person to person, and the country is now moving forward with plans to produce millions of vaccine doses.

The FDA has approved several bird flu vaccines since 2007. The U.S. has flu vaccines in stockpile through the National Pre-Pandemic Influenza Vaccine Stockpile program, which allows for quick response as strains of the flu virus evolve.

Could this outbreak become a pandemic?

Scientists and researchers are concerned about the possibility of H5N1 spreading among people and causing a pandemic. “Right now, the risk is low, but as time goes on, the potential for mutation to cause widespread human infection increases,” says Sykes.

“I think this virus jumping into cows has shown the urgency to keep tracking [H5N1] a lot more closely now,” Peter Halfmann, research associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Influenza Research Institute tells PGN. “We have our eyes on surveillance now. … We’re keeping a much closer eye, so it’s not going to take us by surprise.”

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

-

Unprocessed 10th Anniversary Edition – by Abbie Jay

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The main premise of this book is cooking…

- With nutritious whole foods

- Without salt, oil, sugar (“SOS”)

It additionally does it without animal products and without gluten, and (per “nutritious whole foods”), and, as the title suggests, avoiding anything that’s more than very minimally processed. Remember, for example, that if something is fermented, then that fermentation is a process, so the food has been processed—just, minimally.

This is a revised edition, and it’s been adjusted to, for example, strip some of the previous “no salt” low-sodium options (such as tamari with 233mg/tsp sodium, compared to salt’s 2,300mg/tsp sodium).

You may be wondering: what’s left? Tasty, well-seasoned, plant-based food, that leans towards the “comfort food” culinary niche.

Enough to sate the author, after her own battles with anorexia and obesity (in that order) and finally, after various hospital trips, getting her diet where it needed to be for the healthy lifestyle that she lives now, while still getting to eat such dishes as “Chef AJ’s Disappearing Lasagna” and peanut butter fudge truffles and 151 more.

Bottom line: if you want whole-food plant-based comfort-food cooking that’s healthy in general and especially heart-healthy, this book has plenty of that.

Click here to check out Unprocessed: 10th Anniversary Edition, and… Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Mental Health Courts Can Struggle to Fulfill Decades-Old Promise

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

GAINESVILLE, Ga. — In early December, Donald Brown stood nervously in the Hall County Courthouse, concerned he’d be sent back to jail.

The 55-year-old struggles with depression, addiction, and suicidal thoughts. He worried a judge would terminate him from a special diversion program meant to keep people with mental illness from being incarcerated. He was failing to keep up with the program’s onerous work and community service requirements.

“I’m kind of scared. I feel kind of defeated,” Brown said.

Last year, Brown threatened to take his life with a gun and his family called 911 seeking help, he said. The police arrived, and Brown was arrested and charged with a felony of firearm possession.

After months in jail, Brown was offered access to the Health Empowerment Linkage and Possibilities, or HELP, Court. If he pleaded guilty, he’d be connected to services and avoid prison time. But if he didn’t complete the program, he’d possibly face incarceration.

“It’s almost like coercion,” Brown said. “‘Here, sign these papers and get out of jail.’ I feel like I could have been dealt with a lot better.”

Advocates, attorneys, clinicians, and researchers said courts such as the one Brown is navigating can struggle to live up to their promise. The diversion programs, they said, are often expensive and resource-intensive, and serve fewer than 1% of the more than 2 million people who have a serious mental illness and are booked into U.S. jails each year.

People can feel pressured to take plea deals and enter the courts, seeing the programs as the only route to get care or avoid prison time. The courts are selective, due in part to political pressures on elected judges and prosecutors. Participants must often meet strict requirements that critics say aren’t treatment-focused, such as regular hearings and drug screenings.

And there is a lack of conclusive evidence on whether the courts help participants long-term. Some legal experts, like Lea Johnston, a professor of law at the University of Florida, worry the programs distract from more meaningful investments in mental health resources.

Jails and prisons are not the place for individuals with mental disorders, she said. “But I’m also not sure that mental health court is the solution.”

The country’s first mental health court was established in Broward County, Florida, in 1997, “as a way to promote recovery and mental health wellness and avoid criminalizing mental health problems.” The model was replicated with millions in funding from such federal agencies as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Department of Justice.

More than 650 adult and juvenile mental health courts were operational as of 2022, according to the National Treatment Court Resource Center. There’s no set way to run them. Generally, participants receive treatment plans and get linked to services. Judges and mental health clinicians oversee their progress.

Researchers from the center found little evidence that the courts improve participants’ mental health or keep them out of the criminal justice system. “Few studies … assess longer-term impacts” of the programs “beyond one year after program exit,” said a 2022 policy brief on mental health courts.

The courts work best when paired with investments in services such as clinical treatment, recovery programs, and housing and employment opportunities, said Kristen DeVall, the center’s co-director.

“If all of these other supports aren’t invested in, then it’s kind of a wash,” she said.

The courts should be seen as “one intervention in that larger system,” DeVall said, not “the only resource to serve folks with mental health needs” who get caught up in the criminal justice system.

Resource limitations can also increase the pressures to apply for mental health court programs, said Lisa M. Wayne, executive director of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. People seeking help might not feel they have alternatives.

“It’s not going to be people who can afford mental health intervention. It’s poor people, marginalized folks,” she said.

Other court skeptics wonder about the larger costs of the programs.

In a study of a mental health court in Pennsylvania, Johnston and a University of Florida colleague found participants were sentenced to longer time under government supervision than if they’d gone through the regular criminal justice system.

“The bigger problem is they’re taking attention away from more important solutions that we should be investing in, like community mental health care,” Johnston said.

When Melissa Vergara’s oldest son, Mychael Difrancisco, was arrested on felony gun charges in Queens in May 2021, she thought he would be an ideal candidate for the New York City borough’s mental health court because of his diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder and other behavioral health conditions.

She estimated she spent tens of thousands of dollars to prepare Difrancisco’s case for consideration. Meanwhile, her son sat in jail on Rikers Island, where she said he was assaulted multiple times and had to get half a finger amputated after it was caught in a cell door.

In the end, his case was denied diversion into mental health court. Difrancisco, 22, is serving a prison sentence that could be as long as four years and six months.

“There’s no real urgency to help people with mental health struggles,” Vergara said.

Critics worry such high bars to entry can lead the programs to exclude people who could benefit the most. Some courts don’t allow those accused of violent or sexual crimes to participate. Prosecutors and judges can face pressure from constituents that may lead them to block individuals accused of high-profile offenses.

And judges often aren’t trained to make decisions about participants’ care, said Raji Edayathumangalam, senior policy social worker with New York County Defender Services.

“It’s inappropriate,” she said. “We’re all licensed to practice in our different professions for a reason. I can’t show up to do a hernia operation just because I read about it or sat next to a hernia surgeon.”

Mental health courts can be overly focused on requirements such as drug testing, medication compliance, and completing workbook assignments, rather than progress toward recovery and clinical improvement, Edayathumangalam said.

Completing the programs can leave some participants with clean criminal records. But failing to meet a program’s requirements can trigger penalties — including incarceration.

During a recent hearing in the Clayton County Behavioral Health Accountability Court in suburban Atlanta, one woman left the courtroom in tears when Judge Shana Rooks Malone ordered her to report to jail for a seven-day stay for “being dishonest” about whether she was taking court-required medication.

It was her sixth infraction in the program — previous consequences included written assignments and “bench duty,” in which participants must sit and think about their participation in the program.

“I don’t like to incarcerate,” Malone said. “That particular participant has had some challenges. I’m rooting for her. But all the smaller penalties haven’t worked.”

Still, other participants praised Malone and her program. And, in general, some say such diversion programs provide a much-needed lifeline.

Michael Hobby, 32, of Gainesville was addicted to heroin and fentanyl when he was arrested for drug possession in August 2021. After entry into the HELP Court program, he got sober, started taking medication for anxiety and depression, and built a stable life.

“I didn’t know where to reach out for help,” he said. “I got put in handcuffs, and it saved my life.”

Even as Donald Brown awaited his fate, he said he had started taking medication to manage his depression and has stayed sober because of HELP Court.

“I’ve learned a new way of life. Instead of getting high, I’m learning to feel things now,” he said.

Brown avoided jail that early December day. A hearing to decide his fate could happen in the next few weeks. But even if he’s allowed to remain in the program, Brown said, he’s worried it’s only a matter of time before he falls out of compliance.

“To try to improve myself and get locked up for it is just a kick in the gut,” he said. “I tried really hard.”

KFF Health News senior correspondent Fred Clasen-Kelly contributed to this report.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Dry Needling for Meralgia Paresthetica?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Could you address dry needling, who should administer it, and could it be a remedy for meralgia paresthetica? If not, could you speak to home-based remedies for meralgia paresthetica? Thank you?❞

We’ll need to take a main feature some time to answer this one fully, but we will say some quick things here:

- Dry needling, much like acupuncture, has been found to help with pain relief.

- Meralgia paresthetica, being a neuropathy, may benefit from some things that benefit people with peripheral neuropathy, such as lion’s mane mushroom. There is definitely not research to support this hypothesis yet though (so far as we could find anyway; there is plenty to support lion’s mane helping with nerve regeneration in general, but nothing specific for meralgia paresthetica).

Some previous articles you might enjoy meanwhile:

- Pinpointing The Usefulness Of Acupuncture

- Science-Based Alternative Pain Relief

- Peripheral Neuropathy: How To Avoid It, Manage It, Treat It

- What Does Lion’s Mane Actually Do, Anyway?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Homeopathy: Evidence So Tiny That It’s Not there?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Homeopathy: Evidence So Tiny That It’s Not There?

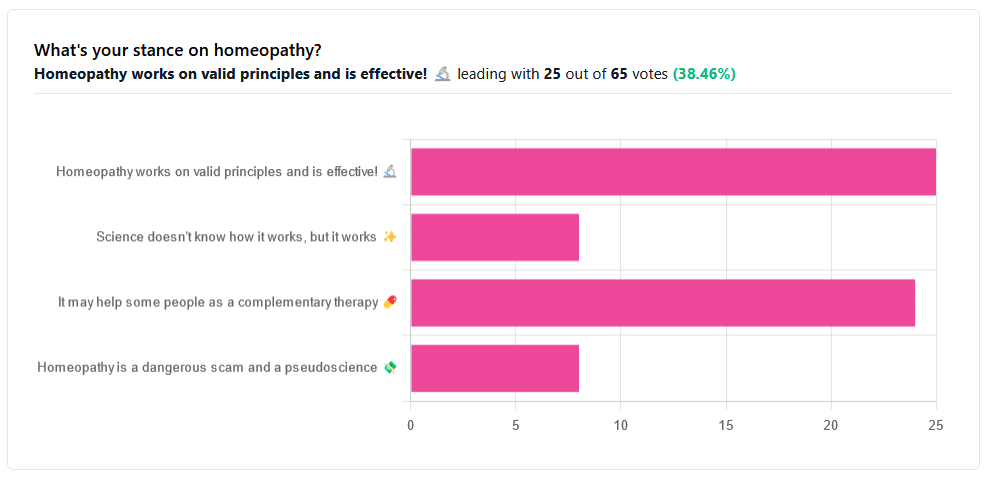

Yesterday, we asked you your opinions on homeopathy. The sample size of responses was a little lower than we usually get, but of those who did reply, there was a clear trend:

- A lot of enthusiasm for “Homeopathy works on valid principles and is effective”

- Near equal support for “It may help some people as a complementary therapy”

- Very few people voted for “Science doesn’t know how it works, but it works”; this is probably because people who considered voting for this, voted for the more flexible “It may help some people as a complementary therapy” instead.

- Very few people considered it a dangerous scam and a pseudoscience.

So, what does the science say?

Well, let us start our investigation by checking out the position of the UK’s National Health Service, an organization with a strong focus on providing the least expensive treatments that are effective.

Since homeopathy is very inexpensive to arrange, they will surely want to put it atop their list of treatments, right?

❝Homeopathy is a “treatment” based on the use of highly diluted substances, which practitioners claim can cause the body to heal itself.

There’s been extensive investigation of the effectiveness of homeopathy. There’s no good-quality evidence that homeopathy is effective as a treatment for any health condition.❞

The NHS actually has a lot more to say about that, and you can read their full statement here.

But that’s just one institution. Here’s what Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council had to say:

❝There was no reliable evidence from research in humans that homeopathy was effective for treating the range of health conditions considered: no good-quality, well-designed studies with enough participants for a meaningful result reported either that homeopathy caused greater health improvements than placebo, or caused health improvements equal to those of another treatment❞

You can read their full statement here.

The American FDA, meanwhile, have a stronger statement:

❝Homeopathic drug products are made from a wide range of substances, including ingredients derived from plants, healthy or diseased animal or human sources, minerals and chemicals, including known poisons. These products have the potential to cause significant and even permanent harm if they are poorly manufactured, since that could lead to contaminated products or products that have potentially toxic ingredients at higher levels than are labeled and/or safe, or if they are marketed as substitute treatments for serious or life-threatening diseases and conditions, or to vulnerable populations.❞

You can read their full statement here.

Homeopathy is a dangerous scam and a pseudoscience: True or False?

False and True, respectively, mostly.

That may be a confusing answer, so let’s elaborate:

- Is it dangerous? Mostly not; it’s mostly just water. However, two possibilities for harm exist:

- Careless preparation could result in a harmful ingredient still being present in the water—and because of the “like cures like” principle, many of the ingredients used in homeopathy are harmful, ranging from heavy metals to plant-based neurotoxins. However, the process of “ultra-dilution” usually removes these so thoroughly that they are absent or otherwise scientifically undetectable.

- Placebo treatment has its place, but could result in “real” treatment going undelivered. This can cause harm if the “real” treatment was critically needed, especially if it was needed on a short timescale.

- Is it a scam? Probably mostly not; to be a scam requires malintent. Most practitioners probably believe in what they are practising.

- Is it a pseudoscience? With the exception that placebo effect has been highly studied and is a very valid complementary therapy… Yes, aside from that it is a pseudoscience. There is no scientific evidence to support homeopathy’s “like cures like” principle, and there is no scientific evidence to support homeopathy’s “water memory” idea. On the contrary, they go against the commonly understood physics of our world.

It may help some people as a complementary therapy: True or False?

True! Not only is placebo effect very well-studied, but best of all, it can still work as a placebo even if you know that you’re taking a placebo… Provided you also believe that!

Science doesn’t know how it works, but it works: True or False?

False, simply. At best, it performs as a placebo.

Placebo is most effective when it’s a remedy against subjective symptoms, like pain.

However, psychosomatic effect (the effect that our brain has on the rest of our body, to which it is very well-connected) can mean that placebo can also help against objective symptoms, like inflammation.

After all, our body, directed primarily by the brain, can “decide” what immunological defenses to deploy or hold back, for example. This is why placebo can help with conditions as diverse as arthritis (an inflammatory condition) or diabetes (an autoimmune condition, and/or a metabolic condition, depending on type).

Here’s how homeopathy measures up, for those conditions:

(the short answer is “no better than placebo”)

Homeopathy works on valid principles and is effective: True or False?

False, except insofar as placebo is a valid principle and can be effective.

The stated principles of homeopathy—”like cures like” and “water memory”—have no scientific basis.

We’d love to show the science for this, but we cannot prove a negative.

However, the ideas were conceived in 1796, and are tantamount to alchemy. A good scientific attitude means being open-minded to new ideas and testing them. In homeopathy’s case, this has been done, extensively, and more than 200 years of testing later, homeopathy has consistently performed equal to placebo.

In summary…

- If you’re enjoying homeopathic treatment and that’s working for you, great, keep at it.

- If you’re open-minded to enjoying a placebo treatment that may benefit you, be careful, but don’t let us stop you.

- If your condition is serious, please do not delay seeking evidence-based medical treatment.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Rise Of The Machines

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In this week’s health science news, several pieces of technology caught our eye. Let’s hope these things roll out widely!

When it comes to UTIs, antimicrobial resistance is taking the p—

This has implications far beyond UTIs—though UTIs can be a bit of a “canary in the coal mine” for antimicrobial resistance. The more people are using antibiotics (intentionally, or because they are in the food chain), the more killer bugs are proliferating instead of dying when we give them something to kill them. And yes: they do proliferate sometimes when given antibiotics, not because the antibiotics did anything directly good for them, but because they killed their (often friendly bacteria) competition. Thus making for a double-whammy of woe.

This development tackles that, by using AI modelling to crunch the numbers of a real-time data-driven personalized approach to give much more accurate treatment options, in a way that a human couldn’t (or at least, couldn’t at anything like the same speed, and most family physicians don’t have a mathematician locked in the back room to spend the night working on a patient’s data).

Read in full: AI can help tackle urinary tract infections and antimicrobial resistance

Related: AI: The Doctor That Never Tires?

When it comes to CPR and women, people are feint of heart

When CPR is needed, time is very much of the essence. And yet, bystanders are much less likely to give CPR to a woman than to a man. Not only that, but CPR-training is part of what leads to this reluctance when it comes to women: the mannequins used are very homogenous, being male (94%) and lean (99%). They’re also usually white (88%) even in countries where the populations are not, but that is less critical. After all, a racist person is less likely to give CPR to a person of color regardless of what color the training mannequin was.

However, the mannequins being male and lean is an issue, because it means people suddenly lack confidence when faced with breasts and/or abundant body fat. Both can prompt the bystander to wonder if some different technique is needed (it isn’t), and breasts can also prompt the bystander to fear doing something potentially “improper” (the proper course of action is: save a person’s life; do not get distracted by breasts).

Read in full: Women are less likely to receive CPR than men. Training on manikins with breasts could help ← there are also CPR instructions (and a video demonstration) there, for anyone who wants a refresher, if perhaps your last first-aid course was a while ago!

Related: Heart Attack: His & Hers (Be Prepared!)

When technology is a breath of fresh air

A woman with COPD and COVID has had her very damaged lungs replaced using a da Vinci X robot to perform a minimally-invasive surgery (which is quite a statement, when it comes to replacing someone’s lungs).

Not without human oversight though—surgeon Dr. Stephanie Chang was directing the transplant. Surgery is rarely fun for the person being operated on, but advances like this make things go a lot more smoothly, so this kind of progress is good to see.

Read in full: Woman receives world’s first robotic double-lung transplant

Related: Why Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Is More Likely Than You Think

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: