Kiwi Fruit vs Pineapple – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kiwi fruit to pineapple, we picked the kiwi.

Why?

In terms of macros, they’re mostly quite comparable, being fruits made of mostly water, and a similar carb count (slightly different proportions of sugar types, but nothing that throws out the end result, and the GI is low for both). Technically kiwi has twice the protein, but they are fruits and “twice the protein” means “0.5g difference per 100g”. Aside from that, and more meaningfully, kiwi also has twice the fiber.

When it comes to vitamins, kiwi has more of vitamins A, B9, C, E, K, and choline, while pineapple has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, and B6. This would be a marginal (6:5) win for kiwi, but kiwi’s margins of difference are greater per vitamin, including 72x more vitamin E (with a cupful giving 29% of the RDA, vs a cupful of pineapple giving 0.4% of the RDA) and 57x more vitamin K (with a cupful giving a day’s RDA, vs a cupful of pineapple giving a little under 2% of the RDA). So, this is a fair win for kiwi.

In the category of minerals, things are clear: kiwi has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while pineapple has more manganese. An overwhelming win for kiwi.

Looking at their respective anti-inflammatory powers, pineapple has its special bromelain enzymes, which is a point in its favour, but when it comes to actual polyphenols, the two fruits are quite balanced, with kiwi’s flavonoids vs pineapple’s lignans.

Adding up the sections, it’s a clear win for kiwi—but pineapple is a very respectable fruit too (especially because of its bromelain content), so do enjoy both!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Bromelain vs Inflammation & Much More

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Move over, COVID and Flu! We Have “Hybrid Viruses” To Contend With Now

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Move over, COVID and Flu! We have “hybrid viruses” to contend with now

COVID and influenza viruses can be serious, of course, so let’s be clear up front that we’re not being dismissive of those. But, most people are hearing a lot about them, whereas respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) has flown under a lot of radars.

Simply put, until recently it hasn’t been considered much of a threat except to the young, the old, or people with other respiratory illnesses. Only these days, the prevalence of “other respiratory illnesses” is a lot higher than it used to be!

It’s not just a comorbidity

It’s easy to think “well of course if you have more than one illness at once, especially similar ones, that’s going to suck” but it’s a bit more than that; it produces newer, more interesting, hybrid viruses. Here’s a research paper from last year’s “flu season”:

Coinfection by influenza A virus and respiratory syncytial virus produces hybrid virus particles

Best to be aware of this if you’re in the “older” age-range

It’s not just that the older we are, the more likely we are to get it. Critically, the older we are, the more likely we are to be hospitalized by it.

And..the older we are, the less likely we are to come back from hospital if hospitalized by it.

Some years back, the intensive care and mortality rates for people over the age of 65 were 8% and 7%, respectively:

Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults

…but a new study this year has found the rates like to be 2.2x that, i.e. 15% intensive care rate and 18% mortality, respectively:

Want to know more?

Here are some hot-off-the-press news articles on the topic:

- Better awareness of RSV in older adults is needed to reduce hospitalizations

- Is there also a connection between RSV and asthma?

- Respiratory syncytial virus coinfections conspire to worsen disease

And as for what to do…

Same general advice as for COVID and Flu, just, ever-more important:

- Try to keep to well-ventilated places as much as possible

- Get any worrying symptoms checked out quickly

- Mask up when appropriate

- Get your shots as appropriate

See also:

Harvard Health Review | Fall shots: Who’s most vulnerable to RSV, COVID, and the flu, and which shots are the right choice for you to help protect against serious illness and hospitalization?

Stay safe!

Share This Post

-

The Vitamin Solution – by Dr. Romy Block & Dr. Arielle Levitan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A quick note: it would be remiss of us not to mention that the authors of this book are also the founders of a vitamin company, thus presenting a potential conflict of interest.

That said… In this reviewer’s opinion, the book does seem balanced and objective, regardless.

We talk a lot about supplements here at 10almonds, especially in our Monday Research Review editions. And yesterday, we featured a book by a doctor who hates supplements. Today, we feature a book by two doctors who have made them their business.

The authors cover all the most common vitamins and minerals popularly enjoyed as supplements, and examine:

- why people take them

- factors affecting whether they help

- problems that can arise

- complicating factors

The “complicating factors” include, for example, the way many vitamins and/or minerals interplay with each other, either by requiring the presence of another, or else competing for resources for absorption, or needing to be delicately balanced on pain of diverse woes.

This is the greatest value of the book, perhaps; it’s where most people go wrong with supplementation, if they go wrong.

While both authors are medical doctors, Dr. Romy Block is an endocrinologist specifically, and she clearly brought a lot of extra attention to relevant metabolic/thyroid issues, and how vitamins and minerals (such as thiamin and iron) can improve or sabotage such, depending on various factors that she explains. Informative, and so far as this reviewer could see, objective and well-balanced.

Bottom line: supplementation is a vast and complex topic, but this book does a fine job of demystifying and simplifying it in a clear and objective fashion, without resorting to either scaremongering or hype.

Click here to check out The Vitamin Solution, and upgrade your knowledge!

Share This Post

-

No More Aches/Tripping When Walking: Strengthen This Oft-Neglected Muscle

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Aches and pains while walking (in the feet, shins, and/or knees), as well as fatigue, are actually mostly about the oft-neglected tibialis anterior muscle.

Fortunately, it’s quite easy to strengthen if you know how:

All about the tib

The tibialis anterior is located at the front of the shin. It lifts the toes when walking, preventing trips and stumbles. Weakness in this muscle can cause fatigue as other muscles compensate, tripping as feet catch the floor, and/or general instability while walking.

Happily, there is an easy exercise to do that gives results quite quickly:

Steps:

- Stand with back and shoulders against a wall, feet 12 inches away.

- Slightly bend knees and keep posture relaxed.

- Lift toes off the ground, hold for a few seconds, then lower.

- Repeat for 10–15 reps.

To increase difficulty:

- Step further away from the wall for more ankle movement.

- Perform a “Tib Plank” by lifting hips off the wall and keeping knees straight.

It’s recommended to do 3 sets per day, with 1-minute rests between.

For more on all of this plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

The Secret to Better Squats: Foot, Knee, & Ankle Mobility

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Studies of Parkinson’s disease have long overlooked Pacific populations – our work shows why that must change

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A form of Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in a gene known as PINK1 has long been labelled rare. But our research shows it’s anything but – at least for some populations.

Our meta-analysis revealed that people in specific Polynesian communities have a much higher rate of PINK1-linked Parkinson’s than expected. This finding reshapes not only our understanding of who is most at risk, but also how soon symptoms may appear and what that might mean for treatment and testing.

Parkinson’s disease is often thought of as a single condition. In reality, it is better understood as a group of syndromes caused by different factors – genetic, environmental or a combination of both.

These varying causes lead to differences in disease patterns, progression and subsequent diagnosis. Recognising this distinction is crucial as it paves the way for targeted interventions and may even help prevent the disease altogether.

Shutterstock/sfam_photo Why we focus on PINK1-linked Parkinson’s

We became interested in this gene after a 2021 study highlighted five people of Samoan and Tongan descent living in New Zealand who shared the same PINK1 mutation.

Previously, this mutation had been spotted only in a few more distant places –Malaysia, Guam and the Philippines. The fact it appeared in people from Samoan and Tongan backgrounds suggested a historical connection dating back to early Polynesian migrations.

One person in 1,300 West Polynesians carries this mutation. This is a frequency well above what scientists usually classify as rare (below one in 2,200). This discovery means we may be overlooking entire communities in Parkinson’s research if we continue to assume PINK1-linked cases are uncommon.

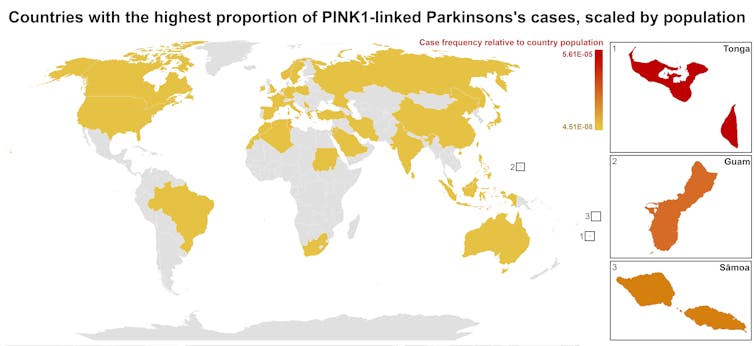

This world map shows people in some Polynesian communities have a much higher rate of PINK1-linked Parkinson’s than the global population. Eden Yin, CC BY-SA Traditional understanding says PINK1-linked Parkinson’s is both rare and typically strikes younger people, mostly in their 30s or 40s, if they inherit two faulty copies of the gene. In other words, it’s considered a recessive condition, needing two matching puzzle pieces before the disease can unfold.

Our work challenges this view. We show that even one defective PINK1 gene can cause Parkinson’s at an average age of 43, much earlier than the typical onset after 65. That’s a significant departure from the standard belief that only people with two defective gene copies are at risk.

Why this matters for people with the disease

It’s not just genetics that challenge long-held views. Historically, PINK1-linked Parkinson’s was thought to lack some of the classic features of the disease, such as toxic clumps of alpha-synuclein protein.

In typical Parkinson’s, alpha-synuclein builds up in the brain, forming sticky clumps known as Lewy bodies. Our results, contrary to prior beliefs, show that alpha-synuclein pathology is present in 87.5% of PINK1 cases. This finding opens up a promising new avenue for future treatment development.

The biggest concern is early onset. PINK1-linked Parkinson’s can begin as early as 11 years old, although a more common starting point is around the mid-30s. This early onset means living longer with the disease, which can profoundly affect education, work opportunities and family life.

Current treatments (such as levodopa, a precursor of dopamine) help manage symptoms, but they’re not designed to address the root cause. If we know someone has a PINK1 mutation, scientists and clinicians can explore therapies for specific genetic pathways, potentially delivering relief beyond symptom management.

Sex differences add a layer of complexity

In Parkinson’s, generally, men are at higher risk and tend to develop symptoms earlier. However, our findings suggest the opposite pattern for PINK1-linked cases. Particularly, women with two defective copies of the gene experience onset earlier than men.

This highlights the need to consider sex-related factors in Parkinson’s research. Overlooking them risks missing key elements of the disease.

Genetic testing could be a game-changer for PINK1-linked Parkinson’s. Because it often appears earlier, doctors may not recognise it immediately, especially if they are more familiar with the common, later-onset form of Parkinson’s.

Early genetic testing could lead to a faster, more accurate diagnosis, allowing treatment to begin when interventions are most effective. It would help families understand how the disease is inherited, enabling relatives to get tested.

In some cases, where appropriate and culturally acceptable, embryo screening may be considered to prevent the passing of the faulty gene.

Knowing you have a PINK1 mutation could also make finding the right treatment more efficient. Instead of a lengthy trial-and-error process with different medications, doctors could use emerging therapies designed to target the underlying PINK1 mutation rather than relying on general Parkinson’s treatments meant for the broader population.

Addressing research gaps

These findings underscore how crucial it is to include diverse populations in health research.

Many communities, such as those in Samoa, Tonga and other Pacific nations, have had little to no involvement in global Parkinson’s genetics studies. This has created gaps in knowledge and real-world consequences for people who may not receive timely or accurate diagnoses.

Researchers, funding bodies and policymakers must prioritise projects beyond the usual focus on European or industrialised countries to ensure research findings and treatments are relevant to all affected populations.

To better diagnose and treat Parkinson’s, we need a more inclusive approach. Recognising that PINK1-linked Parkinson’s is not as rare as previously thought – and that genetics, sex differences and cultural factors all play a role – allows us to improve care for everyone.

By expanding genetic testing, refining treatments and ensuring research reflects the full spectrum of Parkinson’s, we can move closer to more precise diagnoses, targeted therapies and better support systems for all.

Victor Dieriks, Research Fellow in Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau and Eden Paige Yin, PhD candidate in Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Trout vs Haddock – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing trout to haddock, we picked the trout.

Why?

It wasn’t close.

In terms of macros, trout has more protein and more fat, although the fat is mostly healthy (some saturated though, and trout does have more cholesterol). This category could be a win for either, depending on your priorities. But…

When it comes to vitamins, trout has a lot more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B12, C, D, and E, while haddock is not higher in any vitamins.

In the category of minerals, trout has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, potassium, and zinc, while haddock has slightly more selenium. Given that a 10oz portion of trout already contains 153% of the RDA of selenium, however, the same size portion of haddock having 173% of the RDA isn’t really a plus for haddock (especially as selenium can cause problems if we get too much). Oh, and haddock is also higher in sodium, but in industrialized countries, most people most of the time need less of that, not more.

On balance, the overwhelming nutritional density of trout wins the day.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Farmed Fish vs Wild Caught: It Makes Quite A Difference!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Distracted Mind – by Dr. Adam Gazzaley and Dr. Larry Rosen

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Yes, yes, we know, unplug once in a while. But what else do this highly-qualified pair of neuroscientists have to offer?

Rather than being a book for the sake of being a book, with lots of fluff and the usual advice about single-tasking, the authors start with a reframe:

Neurologically speaking, the hit of dopamine we get when looking for information is the exact same as the hit of dopamine that we, a couple of hundred thousand years ago, got when looking for nuts and berries.

- When we don’t find them, we become stressed, and search more.

- When we do find them, we are encouraged and search more nearby, and to the other side of nearby, and near around, to find more.

But in the case of information (be it useful information or celebrity gossip or anything in between), the Internet means that’s always available now.

So, we jitter around like squirrels, hopping from one to the next to the next.

A strength of this book is where it goes from there. Specifically, what evidence-based practices will actually keep our squirrel-brain focused… and which are wishful thinking for anyone who lives in this century.

Bringing original research from their own labs, as well as studies taken from elsewhere, the authors present a science-based toolkit of genuinely useful resources for actual focus.

Bottom line: if you think you could really optimize your life if you could just get on track and stay on track, this is the book for you.

Click here to check out The Distracted Mind, and get yours to focus!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: