How To Lower Your Blood Pressure (Cardiologists Explain)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Today we enjoy the benefit of input from Dr. Zalzal, Dr. Weeing, and Dr. Hefferman!

If the thought of being in an operating room with three cardiologists in scrubs doesn’t raise your blood pressure too much, the doctors in question have a lot to offer for bringing those numbers down and keeping them down! They recommend…

150 mins of Exercise

This isn’t exactly controversial, but: move your body!

See also: Exercise Less; Move More

Reduce salt

Most people eating the Standard American Diet (SAD) are getting far too much—mostly because it’s in so many processed foods already.

See also: How Too Much Salt May Lead To Organ Failure

Eating habits

There’s a lot more to eating healthily for the heart than just reducing salt, and over all, the Mediterranean diet comes out scoring highest:

- What Is The Mediterranean Diet Anyway? ← a primer for the uncertain

- Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean ← includes a heart-specialized version!

Reduce alcohol

According to the WHO, the only healthy amount of alcohol is zero. According to these cardiologists: at the very least cut down. However much or little you’re drinking right now, less is better.

See also: How To Reduce Or Quit Alcohol

Maintain healthy weight

While the doctors agree that BMI isn’t a great method of measuring metabolic health, it is clear that carrying excessive weight isn’t good for the heart.

See also: Lose Weight (Healthily!)

No smoking

This one’s pretty straight forward: just don’t.

See also: Addiction Myths That Are Hard To Quit

Reduce stress

Chronic stress has a big impact on chronic health in general and that includes its effect on blood pressure. So, improving one improves the other.

See also: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

Good sleep

Quality matters as much as quantity, and that goes for its effect on your blood pressure too, so take the time to invest in your good health!

See also: The 6 Dimensions Of Sleep (And Why They Matter)

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Brothy Beans & Greens

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

“Eat beans and greens”, we say, “but how”, you ask. Here’s how! Tasty, filling, and fulfilling, this dish is full of protein, fiber, vitamins, minerals, and assorted powerful phytochemicals.

You will need

- 2½ cups low-sodium vegetable stock

- 2 cans cannellini beans, drained and rinsed

- 1 cup kale, stems removed and roughly chopped

- 4 dried shiitake mushrooms

- 2 shallots, sliced

- ½ bulb garlic, crushed

- 1 tbsp white miso paste

- 1 tbsp nutritional yeast

- 1 tsp rosemary leaves

- 1 tsp thyme leaves

- 1 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- ½ tsp red chili flakes

- Juice of ½ lemon

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Optional: your favorite crusty bread, perhaps using our Delicious Quinoa Avocado Bread recipe

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat some oil in a skillet and fry the shallots for 2–3 minutes.

2) Add the nutritional yeast, garlic, herbs, and spices, and stir for another 1 minute.

3) Add the beans, vegetable stock, and mushrooms. Simmer for 10 minutes.

4) Add the miso paste, stirring well to dissolve and distribute evenly.

5) Add the kale until it begins to wilt, and remove the pot from the heat.

6) Add the lemon juice and stir.

7) Serve; we recommend enjoying it with crusty wholegrain bread.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Dr. Greger’s Daily Dozen ← beans and greens up top!

- The Magic of Mushrooms: “The Longevity Vitamin” (That’s Not A Vitamin)

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Total Recovery – by Dr. Gary Kaplan

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, know: Dr. Kaplan is an osteopath, and as such, will be mostly approaching things from that angle. That said, he is also board certified in other things too, including family medicine, so he’s by no means a “one-trick pony”, nor are there “when your only tool is a hammer, everything starts to look like a nail” problems to be found here. Instead, the scope of the book is quite broad.

Dr. Kaplan talks us through the diagnostic process that a doctor goes through when presented with a patient, what questions need to be asked and answered—and by this we mean the deeper technical questions, e.g. “what do these symptoms have in common”, and “what mechanism was at work when the pain become chronic”, not the very basic questions asked in the initial debriefing with the patient.

He also asks such questions (and questions like these get chapters devoted to them) as “what if physical traumas build up”, and “what if physical and emotional pain influence each other”, and then examines how to interrupt the vicious cycles that lead to deterioration of one’s condition.

The style of the book is very pop-science and often narrative in its presentation, giving lots of anecdotes to illustrate the principles. It’s a “sit down and read it cover-to-cover” book—or a chapter a day, whatever your preferred pace; the point is, it’s not a “dip directly to the part that answers your immediate question” book; it’s not a textbook or manual.

Bottom line: a lot of this work is about prompting the reader to ask the right questions to get to where we need to be, but there are many illustrative possible conclusions and practical advices to be found and given too, making this a useful read if you and/or a loved one suffers from chronic pain.

Click here to check out Total Recovery, and solve your own mysteries!

Share This Post

-

How To Escape From A Despairing Mood

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When we are in a despairing mood, that’s when it can feel hardest to actually implement anything we know about getting out of one. That’s why sometimes, the simplest solutions are the best:

Imagination Is Key

Despairing moods occur when it’s hard to envision a better life. Imagination is the power to envision alternatives, such as new jobs, relationships, or lifestyle, but sadness can cloud our ability to imagine solutions like changing careers, moving house, or starting fresh. With enough imagination, most problems can be worked around—and new opportunities can always be found.

Importantly: we are not bound by our past or present circumstances; we have the freedom and flexibility to choose new paths. That doesn’t mean it’ll always be a walk in the park, but “this too shall pass”.

You may be thinking: “sometimes the hardship does pass, but can last many years”, and that is true. All the more reason to check if there’s a freer lane you can slip into to speed ahead. Even if there isn’t, the mere act of imagining such lanes is already respite from the hardships—and having envisioned such will make it much easier for you to recognise when opportunities for change do come along.

To foster imagination, we are advised to expose ourselves to different narratives, preparing ourselves for alternative ways of living. Thus, we can reframe life’s challenges as intellectual puzzles, urging us to rebuild creatively and find new solutions!

For more on all this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Behavioral Activation Against Depression & Anxiety

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Ageless Athletes – by Dr. Jim Madden

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is an approach to strength and fitness training specifically for the 50+ crowd, and/but even more specifically for the 50+ crowd who do not wish to settle for mediocrity. In short, it’s for those who not only wish to stay healthy and have good mobility, but also who wish to be and remain athletic.

It does not assume extant athleticism, but nor does it assume complete inexperience. It provides a fairly ground-upwards entry to a training program that then quickly proceeds to competitive levels of athleticism.

The author himself details his own journey from being in his 30s, overweight and unfit, to being in his 50s and very athletic, with before and after photos. Granted, those are 20 years in between, but all the same, it’s a good sign when someone gets stronger and fitter with age, rather than declining.

The style of the book is quite casual, and/but after the introductory background and pep talk, is quite pragmatic and drops the additional fluff. In particular, older readers may enjoy the “Old Workhorse” protocol, as a tailored measured progression system.

In terms of expected equipment by the way, some is bodyweight and some is with weights; kettlebells in particular feature strongly, since this is about functional strength and not bodybuilding.

In the category of criticism, he does refer to his other books and generally assumes the reader is reading all his work, so it may not be for everyone as a standalone book.

Bottom line: if you’re 50+ and are wondering how to gain/maintain a high level athleticism, this book can definitely help with that.

Click here to check out Ageless Athlete, and go from strength to strength!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

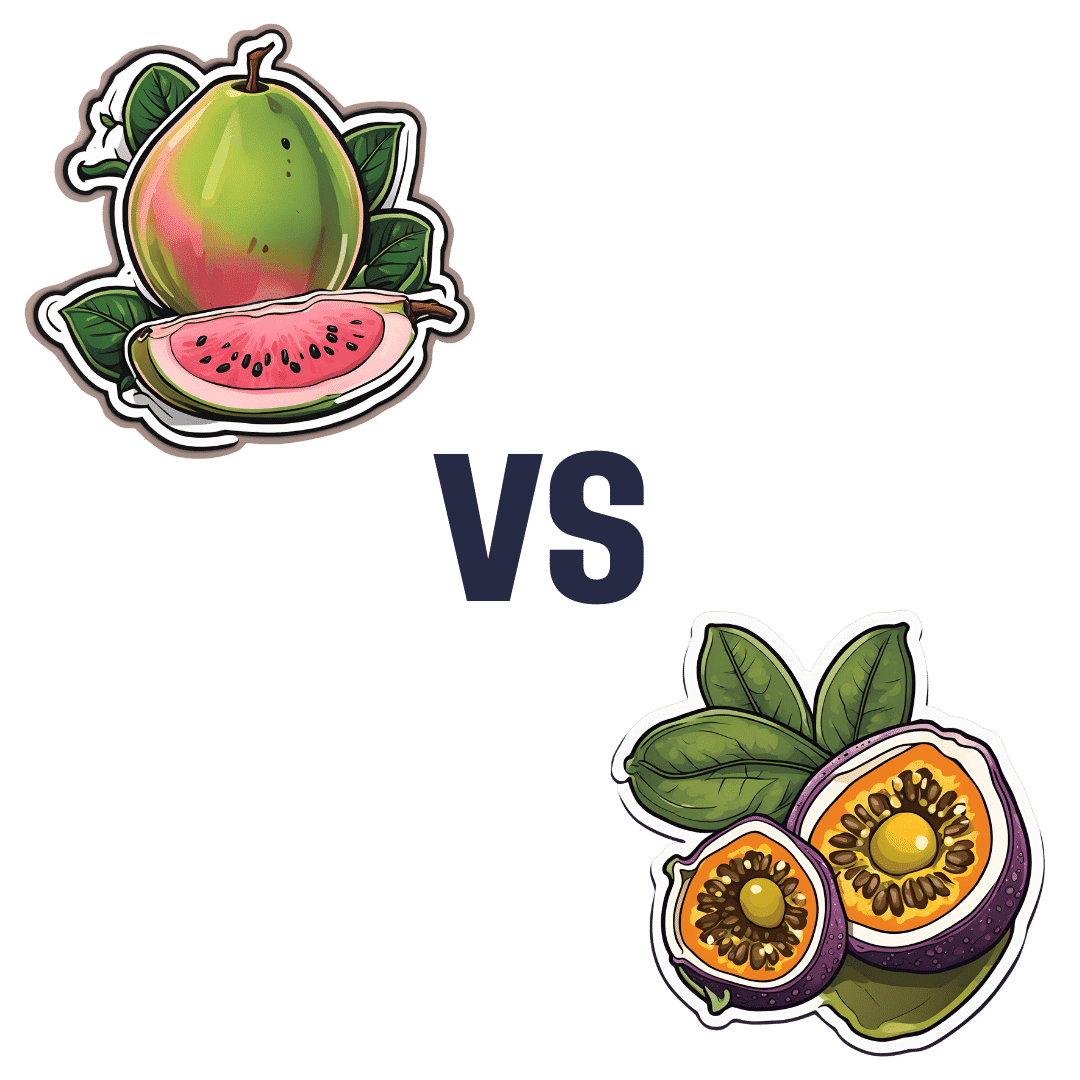

Guava vs Passion Fruit – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing guava to passion fruit, we picked the guava.

Why?

There aren’t many fruits that can beat passion fruit for nutritional density! And even in this case, it wasn’t completely so in every category:

In terms of macros, passion fruit has more carbs and fiber, the ratio of which give it the slightly lower glycemic index. Thus, a modest win for passion fruit in this category.

In the category of vitamins, guava has more of vitamins B1, B5, B6, B9, C, E, and K, while passion fruit has more of vitamins A, B2, and B3. A clear win for guava this time.

When it comes to minerals, it’s a little closer, but: guava has more calcium, copper, manganese, potassium, and zinc, while passion fruit has more iron, magnesium, and phosphorus. So, another win for guava.

Adding up the sections makes for guava winning the day, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Fruit Is Healthy; Juice Isn’t (Here’s Why)

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Radiant Rebellion – by Karen Walrond

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In health terms, we are often about fighting aging here. But to be more specific, what we’re fighting in those cases is not truly aging itself, so much as age-related decline.

Karen Walrond makes a case that we’ve made from the very start of 10almonds (but she wrote a whole book about it), that there’s merit in looking at what we can and can’t control about aging, doing what we reasonably can, and embracing what we can’t.

And yes, embracing, not merely accepting. This is not a downer of a book; it’s a call to revolution. It asks us to be proud of our grey hairs, to see our smile-lines around our eyes as the sign of a lived-in body, and even to embrace some of the unavoidable “actual decline” things as part of the journey of life. Maybe we’re not as strong as we used to be and now need a grippety-doodah to open jars; not everyone gets to live long enough to experience that! How lucky we are.

Perhaps most importantly, she bids us be the change we want to see in the world, and inspire others with our choices and actions, and shake off ageist biases for good.

Bottom line: if you want to foster a better attitude to aging not only for yourself, but also those around you, then this is a top-tier book for that.

Click here to check out Radiant Rebellion, and reclaim aging!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: