How do science journalists decide whether a psychology study is worth covering?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Complex research papers and data flood academic journals daily, and science journalists play a pivotal role in disseminating that information to the public. This can be a daunting task, requiring a keen understanding of the subject matter and the ability to translate dense academic language into narratives that resonate with the general public.

Several resources and tip sheets, including the Know Your Research section here at The Journalist’s Resource, aim to help journalists hone their skills in reporting on academic research.

But what factors do science journalists look for to decide whether a social science research study is trustworthy and newsworthy? That’s the question researchers at the University of California, Davis, and the University of Melbourne in Australia examine in a recent study, “How Do Science Journalists Evaluate Psychology Research?” published in September in Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science.

Their online survey of 181 mostly U.S.-based science journalists looked at how and whether they were influenced by four factors in fictitious research summaries: the sample size (number of participants in the study), sample representativeness (whether the participants in the study were from a convenience sample or a more representative sample), the statistical significance level of the result (just barely statistically significant or well below the significance threshold), and the prestige of a researcher’s university.

The researchers found that sample size was the only factor that had a robust influence on journalists’ ratings of how trustworthy and newsworthy a study finding was.

University prestige had no effect, while the effects of sample representativeness and statistical significance were inconclusive.

But there’s nuance to the findings, the authors note.

“I don’t want people to think that science journalists aren’t paying attention to other things, and are only paying attention to sample size,” says Julia Bottesini, an independent researcher, a recent Ph.D. graduate from the Psychology Department at UC Davis, and the first author of the study.

Overall, the results show that “these journalists are doing a very decent job” vetting research findings, Bottesini says.

Also, the findings from the study are not generalizable to all science journalists or other fields of research, the authors note.

“Instead, our conclusions should be circumscribed to U.S.-based science journalists who are at least somewhat familiar with the statistical and replication challenges facing science,” they write. (Over the past decade a series of projects have found that the results of many studies in psychology and other fields can’t be reproduced, leading to what has been called a ‘replication crisis.’)

“This [study] is just one tiny brick in the wall and I hope other people get excited about this topic and do more research on it,” Bottesini says.

More on the study’s findings

The study’s findings can be useful for researchers who want to better understand how science journalists read their research and what kind of intervention — such as teaching journalists about statistics — can help journalists better understand research papers.

“As an academic, I take away the idea that journalists are a great population to try to study because they’re doing something really important and it’s important to know more about what they’re doing,” says Ellen Peters, director of Center for Science Communication Research at the School of Journalism and Communication at the University of Oregon. Peters, who was not involved in the study, is also a psychologist who studies human judgment and decision-making.

Peters says the study was “overall terrific.” She adds that understanding how journalists do their work “is an incredibly important thing to do because journalists are who reach the majority of the U.S. with science news, so understanding how they’re reading some of our scientific studies and then choosing whether to write about them or not is important.”

The study, conducted between December 2020 and March 2021, is based on an online survey of journalists who said they at least sometimes covered science or other topics related to health, medicine, psychology, social sciences, or well-being. They were offered a $25 Amazon gift card as compensation.

Among the participants, 77% were women, 19% were men, 3% were nonbinary and 1% preferred not to say. About 62% said they had studied physical or natural sciences at the undergraduate level, and 24% at the graduate level. Also, 48% reported having a journalism degree. The study did not include the journalists’ news reporting experience level.

Participants were recruited through the professional network of Christie Aschwanden, an independent journalist and consultant on the study, which could be a source of bias, the authors note.

“Although the size of the sample we obtained (N = 181) suggests we were able to collect a range of perspectives, we suspect this sample is biased by an ‘Aschwanden effect’: that science journalists in the same professional network as C. Aschwanden will be more familiar with issues related to the replication crisis in psychology and subsequent methodological reform, a topic C. Aschwanden has covered extensively in her work,” they write.

Participants were randomly presented with eight of 22 one-paragraph fictitious social and personality psychology research summaries with fictitious authors. The summaries are posted on Open Science Framework, a free and open-source project management tool for researchers by the Center for Open Science, with a mission to increase openness, integrity and reproducibility of research.

For instance, one of the vignettes reads:

“Scientists at Harvard University announced today the results of a study exploring whether introspection can improve cooperation. 550 undergraduates at the university were randomly assigned to either do a breathing exercise or reflect on a series of questions designed to promote introspective thoughts for 5 minutes. Participants then engaged in a cooperative decision-making game, where cooperation resulted in better outcomes. People who spent time on introspection performed significantly better at these cooperative games (t (548) = 3.21, p = 0.001). ‘Introspection seems to promote better cooperation between people,’ says Dr. Quinn, the lead author on the paper.”

In addition to answering multiple-choice survey questions, participants were given the opportunity to answer open-ended questions, such as “What characteristics do you [typically] consider when evaluating the trustworthiness of a scientific finding?”

Bottesini says those responses illuminated how science journalists analyze a research study. Participants often mentioned the prestige of the journal in which it was published or whether the study had been peer-reviewed. Many also seemed to value experimental research designs over observational studies.

Considering statistical significance

When it came to considering p-values, “some answers suggested that journalists do take statistical significance into account, but only very few included explanations that suggested they made any distinction between higher or lower p values; instead, most mentions of p values suggest journalists focused on whether the key result was statistically significant,” the authors write.

Also, many participants mentioned that it was very important to talk to outside experts or researchers in the same field to get a better understanding of the finding and whether it could be trusted, the authors write.

“Journalists also expressed that it was important to understand who funded the study and whether the researchers or funders had any conflicts of interest,” they write.

Participants also “indicated that making claims that were calibrated to the evidence was also important and expressed misgivings about studies for which the conclusions do not follow from the evidence,” the authors write.

In response to the open-ended question, “What characteristics do you [typically] consider when evaluating the trustworthiness of a scientific finding?” some journalists wrote they checked whether the study was overstating conclusions or claims. Below are some of their written responses:

- “Is the researcher adamant that this study of 40 college kids is representative? If so, that’s a red flag.”

- “Whether authors make sweeping generalizations based on the study or take a more measured approach to sharing and promoting it.”

- “Another major point for me is how ‘certain’ the scientists appear to be when commenting on their findings. If a researcher makes claims which I consider to be over-the-top about the validity or impact of their findings, I often won’t cover.”

- “I also look at the difference between what an experiment actually shows versus the conclusion researchers draw from it — if there’s a big gap, that’s a huge red flag.”

Peters says the study’s findings show that “not only are journalists smart, but they have also gone out of their way to get educated about things that should matter.”

What other research shows about science journalists

A 2023 study, published in the International Journal of Communication, based on an online survey of 82 U.S. science journalists, aims to understand what they know and think about open-access research, including peer-reviewed journals and articles that don’t have a paywall, and preprints. Data was collected between October 2021 and February 2022. Preprints are scientific studies that have yet to be peer-reviewed and are shared on open repositories such as medRxiv and bioRxiv. The study finds that its respondents “are aware of OA and related issues and make conscious decisions around which OA scholarly articles they use as sources.”

A 2021 study, published in the Journal of Science Communication, looks at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the work of science journalists. Based on an online survey of 633 science journalists from 77 countries, it finds that the pandemic somewhat brought scientists and science journalists closer together. “For most respondents, scientists were more available and more talkative,” the authors write. The pandemic has also provided an opportunity to explain the scientific process to the public, and remind them that “science is not a finished enterprise,” the authors write.

More than a decade ago, a 2008 study, published in PLOS Medicine, and based on an analysis of 500 health news stories, found that “journalists usually fail to discuss costs, the quality of the evidence, the existence of alternative options, and the absolute magnitude of potential benefits and harms,” when reporting on research studies. Giving time to journalists to research and understand the studies, giving them space for publication and broadcasting of the stories, and training them in understanding academic research are some of the solutions to fill the gaps, writes Gary Schwitzer, the study author.

Advice for journalists

We asked Bottesini, Peters, Aschwanden and Tamar Wilner, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas, who was not involved in the study, to share advice for journalists who cover research studies. Wilner is conducting a study on how journalism research informs the practice of journalism. Here are their tips:

1. Examine the study before reporting it.

Does the study claim match the evidence? “One thing that makes me trust the paper more is if their interpretation of the findings is very calibrated to the kind of evidence that they have,” says Bottesini. In other words, if the study makes a claim in its results that’s far-fetched, the authors should present a lot of evidence to back that claim.

Not all surprising results are newsworthy. If you come across a surprising finding from a single study, Peters advises you to step back and remember Carl Sagan’s quote: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

How transparent are the authors about their data? For instance, are the authors posting information such as their data and the computer codes they use to analyze the data on platforms such as Open Science Framework, AsPredicted, or The Dataverse Project? Some researchers ‘preregister’ their studies, which means they share how they’re planning to analyze the data before they see them. “Transparency doesn’t automatically mean that a study is trustworthy,” but it gives others the chance to double-check the findings, Bottesini says.

Look at the study design. Is it an experimental study or an observational study? Observational studies can show correlations but not causation.

“Observational studies can be very important for suggesting hypotheses and pointing us towards relationships and associations,” Aschwanden says.

Experimental studies can provide stronger evidence toward a cause, but journalists must still be cautious when reporting the results, she advises. “If we end up implying causality, then once it’s published and people see it, it can really take hold,” she says.

Know the difference between preprints and peer-reviewed, published studies. Peer-reviewed papers tend to be of higher quality than those that are not peer-reviewed. Read our tip sheet on the difference between preprints and journal articles.

Beware of predatory journals. Predatory journals are journals that “claim to be legitimate scholarly journals, but misrepresent their publishing practices,” according to a 2020 journal article, published in the journal Toxicologic Pathology, “Predatory Journals: What They Are and How to Avoid Them.”

2. Zoom in on data.

Read the methods section of the study. The methods section of the study usually appears after the introduction and background section. “To me, the methods section is almost the most important part of any scientific paper,” says Aschwanden. “It’s amazing to me how often you read the design and the methods section, and anyone can see that it’s a flawed design. So just giving things a gut-level check can be really important.”

What’s the sample size? Not all good studies have large numbers of participants but pay attention to the claims a study makes with a small sample size. “If you have a small sample, you calibrate your claims to the things you can tell about those people and don’t make big claims based on a little bit of evidence,” says Bottesini.

But also remember that factors such as sample size and p-value are not “as clear cut as some journalists might assume,” says Wilner.

How representative of a population is the study sample? “If the study has a non-representative sample of, say, undergraduate students, and they’re making claims about the general population, that’s kind of a red flag,” says Bottesini. Aschwanden points to the acronym WEIRD, which stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic,” and is used to highlight a lack of diversity in a sample. Studies based on such samples may not be generalizable to the entire population, she says.

Look at the p-value. Statistical significance is both confusing and controversial, but it’s important to consider. Read our tip sheet, “5 Things Journalists Need to Know About Statistical Significance,” to better understand it.

3. Talk to scientists not involved in the study.

If you’re not sure about the quality of a study, ask for help. “Talk to someone who is an expert in study design or statistics to make sure that [the study authors] use the appropriate statistics and that methods they use are appropriate because it’s amazing to me how often they’re not,” says Aschwanden.

Get an opinion from an outside expert. It’s always a good idea to present the study to other researchers in the field, who have no conflicts of interest and are not involved in the research you’re covering and get their opinion. “Don’t take scientists at their word. Look into it. Ask other scientists, preferably the ones who don’t have a conflict of interest with the research,” says Bottesini.

4. Remember that a single study is simply one piece of a growing body of evidence.

“I have a general rule that a single study doesn’t tell us very much; it just gives us proof of concept,” says Peters. “It gives us interesting ideas. It should be retested. We need an accumulation of evidence.”

Aschwanden says as a practice, she tries to avoid reporting stories about individual studies, with some exceptions such as very large, randomized controlled studies that have been underway for a long time and have a large number of participants. “I don’t want to say you never want to write a single-study story, but it always needs to be placed in the context of the rest of the evidence that we have available,” she says.

Wilner advises journalists to spend some time looking at the scope of research on the study’s specific topic and learn how it has been written about and studied up to that point.

“We would want science journalists to be reporting balance of evidence, and not focusing unduly on the findings that are just in front of them in a most recent study,” Wilner says. “And that’s a very difficult thing to as journalists to do because they’re being asked to make their article very newsy, so it’s a difficult balancing act, but we can try and push journalists to do more of that.”

5. Remind readers that science is always changing.

“Science is always two steps forward, one step back,” says Peters. Give the public a notion of uncertainty, she advises. “This is what we know today. It may change tomorrow, but this is the best science that we know of today.”

Aschwanden echoes the sentiment. “All scientific results are provisional, and we need to keep that in mind,” she says. “It doesn’t mean that we can’t know anything, but it’s very important that we don’t overstate things.”

Authors of a study published in PNAS in January analyzed more than 14,000 psychology papers and found that replication success rates differ widely by psychology subfields. That study also found that papers that could not be replicated received more initial press coverage than those that could.

The authors note that the media “plays a significant role in creating the public’s image of science and democratizing knowledge, but it is often incentivized to report on counterintuitive and eye-catching results.”

Ideally, the news media would have a positive relationship with replication success rates in psychology, the authors of the PNAS study write. “Contrary to this ideal, however, we found a negative association between media coverage of a paper and the paper’s likelihood of replication success,” they write. “Therefore, deciding a paper’s merit based on its media coverage is unwise. It would be valuable for the media to remind the audience that new and novel scientific results are only food for thought before future replication confirms their robustness.”

Additional reading

Uncovering the Research Behaviors of Reporters: A Conceptual Framework for Information Literacy in Journalism

Katerine E. Boss, et al. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, October 2022.

The Problem with Psychological Research in the Media

Steven Stosny. Psychology Today, September 2022.

Critically Evaluating Claims

Megha Satyanarayana, The Open Notebook, January 2022.

How Should Journalists Report a Scientific Study?

Charles Binkley and Subramaniam Vincent. Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University, September 2020.

What Journalists Get Wrong About Social Science: Full Responses

Brian Resnick. Vox, January 2016.

From The Journalist’s Resource

8 Ways Journalists Can Access Academic Research for Free

5 Things Journalists Need to Know About Statistical Significance

5 Common Research Designs: A Quick Primer for Journalists

5 Tips for Using PubPeer to Investigate Scientific Research Errors and Misconduct

What’s Standard Deviation? 4 Things Journalists Need to Know

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Chaga Mushrooms’ Immune & Anticancer Potential

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Do Chaga Mushrooms Do?

Chaga mushrooms, which also go by other delightful names including “sterile conk trunk rot” and “black mass”, are a type of fungus that grow on birch trees in cold climates such as Alaska, Northern Canada, Northern Europe, and Siberia.

They’ve enjoyed a long use as a folk remedy in Northern Europe and Siberia, mostly to boost immunity, mostly in the form of a herbal tea.

Let’s see what the science says…

Does it boost the immune system?

It definitely does if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Immunomodulatory Activity of the Water Extract from Medicinal Mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Inonotus obliquus extracts suppress antigen-specific IgE production through the modulation of Th1/Th2 cytokines in ovalbumin-sensitized mice

(cytokines are special proteins that regulate the immune system, and Chaga tells them to tell the body to produce more white blood cells)

Wait, does that mean it increases inflammation?

Definitely not if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Anti-inflammatory effects of orally administered Inonotus obliquus in ulcerative colitis

- Orally administered aqueous extract of Inonotus obliquus ameliorates acute inflammation

Anti-inflammatory things often fight cancer. Does chaga?

Definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies in human cancer patients yet. But for example:

While in vivo human studies are conspicuous by their absence, there have been in vitro human studies, i.e., studies performed on cancerous human cell samples in petri dishes. They are promising:

- Anticancer activities of extracts and compounds from the mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Extract of Innotus obliquus induces G1 cell cycle arrest in human colon cancer cells

- Anticancer activity of Inonotus obliquus extract in human cancer cells

I heard it fights diabetes; does it?

You’ll never see this coming, but: definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any human studies yet. But for example:

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice and potential mechanism

Is it safe?

Honestly, there simply have been no human safety studies to know for sure, or even to establish an appropriate dosage.

Its only-partly-understood effects on blood sugar levels and the immune system may make it more complicated for people with diabetes and/or autoimmune disorders, and such people should definitely seek medical advice before taking chaga.

Additionally, chaga contains a protein that can prevent blood clotting. That might be great by default if you are at risk of blood clots, but not so great if you are already on blood-thinning medication, or otherwise have a bleeding disorder, or are going to have surgery soon.

As with anything, we’re not doctors, let alone your doctors, so please consult yours before trying chaga.

Where can we get it?

We don’t sell it (or anything else), but for your convenience, here’s an example product on Amazon.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Kate Middleton is having ‘preventive chemotherapy’ for cancer. What does this mean?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Catherine, Princess of Wales, is undergoing treatment for cancer. In a video thanking followers for their messages of support after her major abdominal surgery, the Princess of Wales explained, “tests after the operation found cancer had been present.”

“My medical team therefore advised that I should undergo a course of preventative chemotherapy and I am now in the early stages of that treatment,” she said in the two-minute video.

No further details have been released about the Princess of Wales’ treatment.

But many have been asking what preventive chemotherapy is and how effective it can be. Here’s what we know about this type of treatment.

It’s not the same as preventing cancer

To prevent cancer developing, lifestyle changes such as diet, exercise and sun protection are recommended.

Tamoxifen, a hormone therapy drug can be used to reduce the risk of cancer for some patients at high risk of breast cancer.

Aspirin can also be used for those at high risk of bowel and other cancers.

How can chemotherapy be used as preventive therapy?

In terms of treating cancer, prevention refers to giving chemotherapy after the cancer has been removed, to prevent the cancer from returning.

If a cancer is localised (limited to a certain part of the body) with no evidence on scans of it spreading to distant sites, local treatments such as surgery or radiotherapy can remove all of the cancer.

If, however, cancer is first detected after it has spread to distant parts of the body at diagnosis, clinicians use treatments such as chemotherapy (anti-cancer drugs), hormones or immunotherapy, which circulate around the body .

The other use for chemotherapy is to add it before or after surgery or radiotherapy, to prevent the primary cancer coming back. The surgery may have cured the cancer. However, in some cases, undetectable microscopic cells may have spread into the bloodstream to distant sites. This will result in the cancer returning, months or years later.

With some cancers, treatment with chemotherapy, given before or after the local surgery or radiotherapy, can kill those cells and prevent the cancer coming back.

If we can’t see these cells, how do we know that giving additional chemotherapy to prevent recurrence is effective? We’ve learnt this from clinical trials. Researchers have compared patients who had surgery only with those whose surgery was followed by additional (or often called adjuvant) chemotherapy. The additional therapy resulted in patients not relapsing and surviving longer.

How effective is preventive therapy?

The effectiveness of preventive therapy depends on the type of cancer and the type of chemotherapy.

Let’s consider the common example of bowel cancer, which is at high risk of returning after surgery because of its size or spread to local lymph glands. The first chemotherapy tested improved survival by 15%. With more intense chemotherapy, the chance of surviving six years is approaching 80%.

Preventive chemotherapy is usually given for three to six months.

How does chemotherapy work?

Many of the chemotherapy drugs stop cancer cells dividing by disrupting the DNA (genetic material) in the centre of the cells. To improve efficacy, drugs which work at different sites in the cell are given in combinations.

Chemotherapy is not selective for cancer cells. It kills any dividing cells.

But cancers consist of a higher proportion of dividing cells than the normal body cells. A greater proportion of the cancer is killed with each course of chemotherapy.

Normal cells can recover between courses, which are usually given three to four weeks apart.

What are the side effects?

The side effects of chemotherapy are usually reversible and are seen in parts of the body where there is normally a high turnover of cells.

The production of blood cells, for example, is temporarily disrupted. When your white blood cell count is low, there is an increased risk of infection.

Cell death in the lining of the gut leads to mouth ulcers, nausea and vomiting and bowel disturbance.

Certain drugs sometimes given during chemotherapy can attack other organs, such as causing numbness in the hands and feet.

There are also generalised symptoms such as fatigue.

Given that preventive chemotherapy given after surgery starts when there is no evidence of any cancer remaining after local surgery, patients can usually resume normal activities within weeks of completing the courses of chemotherapy.

Ian Olver, Adjunct Professsor, School of Psychology, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Why You Probably Need More Sleep

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sleep: yes, you really do still need it!

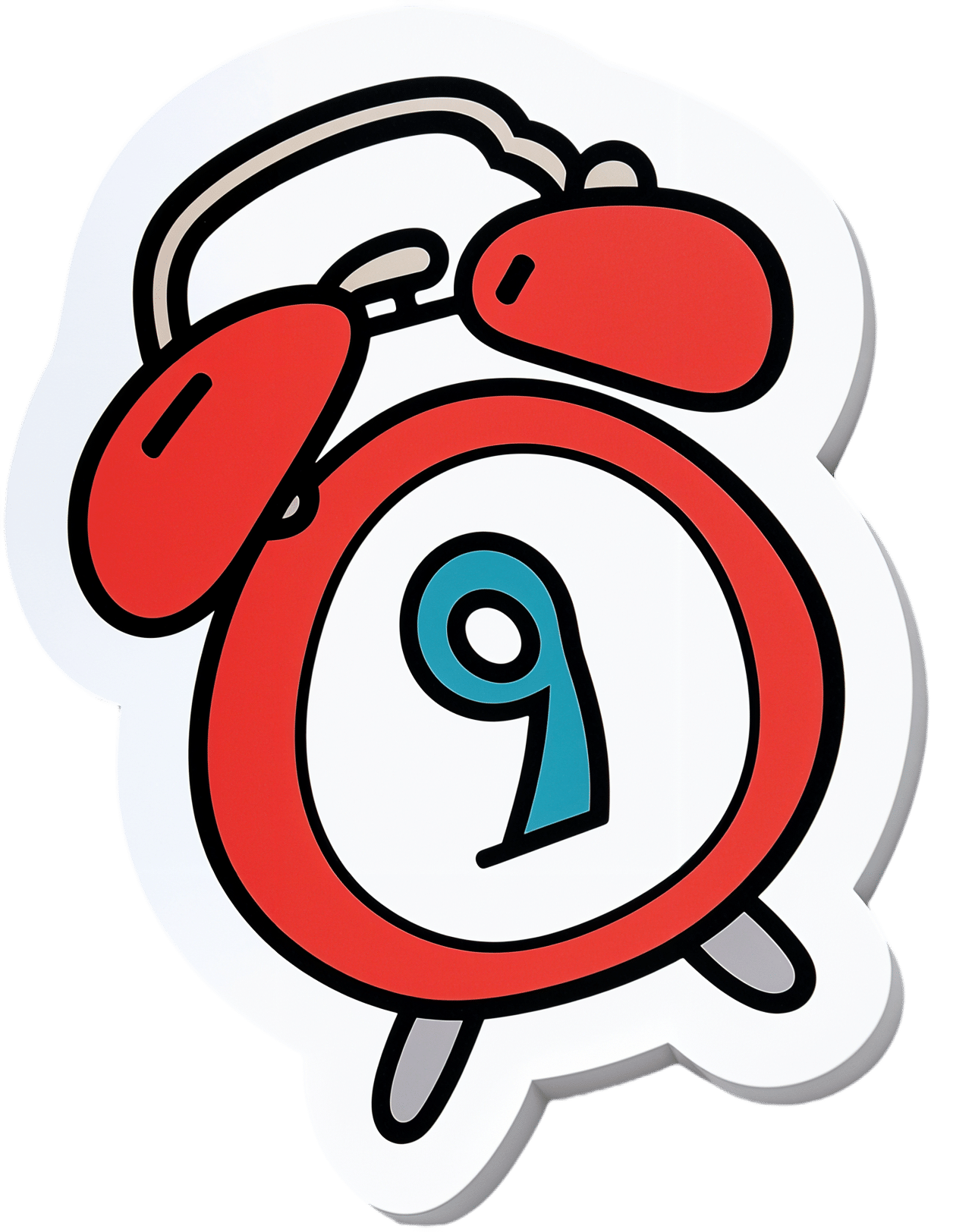

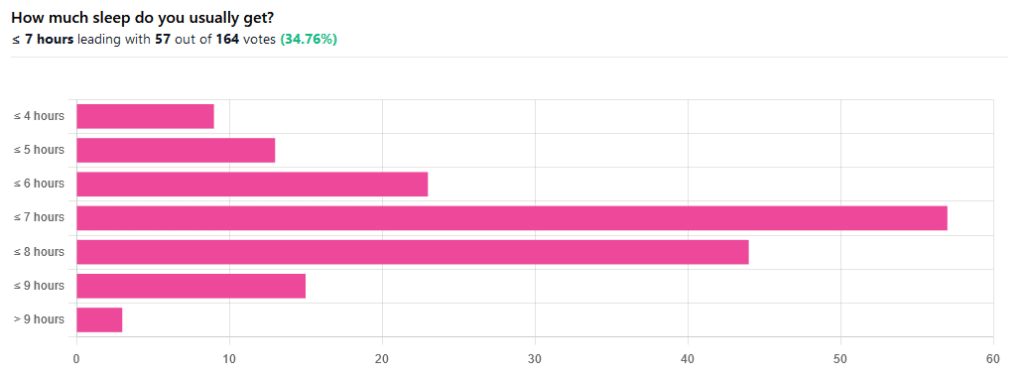

We asked you how much sleep you usually get, and got the above-pictured, below-described set of responses:

- A little of a third of all respondents selected the option “< 7 hours”

- However, because respondents also selected options such as < 6 hours, < 5 hours, and < 4 hours, so if we include those in the tally, the actual total percentage of respondents who reported getting under 7 hours, is actually more like 62%, or just under two thirds of all respondents.

- Nine respondents, which was about 5% of the total, reported usually getting under 4 hours sleep

- A little over quarter of respondents reported usually getting between 7 and 8 hours sleep

- Fifteen respondents, which was a little under 10% of the total, reported usually getting between 8 and 9 hours of sleep

- Three respondents, which was a little under 2% of the total, reported getting over 9 hours of sleep

- In terms of the classic “you should get 7–9 hours sleep”, approximately a third of respondents reported getting this amount.

You need to get 7–9 hours sleep: True or False?

True! Unless you have a (rare!) mutated ADRB1 gene, which reduces that.

The way to know whether you have this, without genomic testing to know for sure, is: do you regularly get under 6.5 hours sleep, and yet continue to go through life bright-eyed and bushy-tailed? If so, you probably have that gene. If you experience daytime fatigue, brain fog, and restlessness, you probably don’t.

About that mutated ADRB1 gene:

NIH | Gene identified in people who need little sleep

Quality of sleep matters as much as duration, and a lot of studies use the “RU-Sated” framework, which assesses six key dimensions of sleep that have been consistently associated with better health outcomes. These are:

- regularity / usual hours

- satisfaction with sleep

- alertness during waking hours

- timing of sleep

- efficiency of sleep

- duration of sleep

But, that doesn’t mean that you can skimp on the last one if the others are in order. In fact, getting a good 7 hours sleep can reduce your risk of getting a cold by three or four times (compared with six or fewer hours):

Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold

^This study was about the common cold, but you may be aware there are more serious respiratory viruses freely available, and you don’t want those, either.

Napping is good for the health: True or False?

True or False, depending on how you’re doing it!

If you’re trying to do it to sleep less in total (per polyphasic sleep scheduling), then no, this will not work in any sustainable fashion and will be ruinous to the health. We did a Mythbusting Friday special on specifically this, a while back:

Could Just Two Hours Sleep Per Day Be Enough?

PS: you might remember Betteridge’s Law of Headlines

If you’re doing it as a energy-boosting supplement to a reasonable night’s sleep, napping can indeed be beneficial to the health, and can give benefits such as:

- Increased alertness

- Helps with learning

- Improved memory

- Boost to immunity

- Enhance athletic performance

However! There is still a right and a wrong way to go about it, and we wrote about this previously, for a Saturday Life Hacks edition of 10almonds:

How To Nap Like A Pro (No More “Sleep Hangovers”!)

As we get older, we need less sleep: True or False

False, with one small caveat.

The small caveat: children and adolescents need 9–12 hours sleep because, uncredited as it goes, they are doing some seriously impressive bodybuilding, and that is exhausting to the body. So, an adult (with a normal lifestyle, who is not a bodybuilder) will tend to need less sleep than a child/adolescent.

But, the statement “As we get older, we need less sleep” is generally taken to mean “People in the 65+ age bracket need less sleep than younger adults”, and this popular myth is based on anecdotal observational evidence: older people tend to sleep less (as our survey above shows! For any who aren’t aware, our readership is heavily weighted towards the 60+ demographic), and still continue functioning, after all.

Just because we survive something with a degree of resilience doesn’t mean it’s good for us.

In fact, there can be serious health risks from not getting enough sleep in later years, for example:

Sleep deficiency promotes Alzheimer’s disease development and progression

Want to get better sleep?

What gets measured, gets done. Sleep tracking apps can be a really good tool for getting one’s sleep on a healthier track. We compared and contrasted some popular ones:

The Head-To-Head Of Google and Apple’s Top Apps For Getting Your Head Down

Take good care of yourself!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Feta Cheese vs Mozzarella – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing feta to mozzarella, we picked the mozzarella.

Why?

There are possible arguments for both, but there are a couple of factors that we think tip the balance.

In terms of macronutrients, feta has more fat, of which, more saturated fat, and more cholesterol. Meanwhile, mozzarella has about twice the protein, which is substantial for a cheese. So this section’s a fair win for mozzarella.

In the category of vitamins, however, feta wins with more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, B12, D, & E. In contrast, mozzarella boasts only a little more vitamin A and choline. An easy win for feta in this section.

When it comes to minerals, the matter is decided, we say. Mozzarella has more calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium, while feta has more copper, iron, and (which counts against it) sodium. A win for mozzarella.

About that sodium… A cup of mozzarella contains about 3% of the RDA of sodium, while a cup of feta contains about 120% of the RDA of sodium. You see the problem? So, while mozzarella was already winning based on adding up the previous categories, the sodium content alone is a reason to choose mozzarella for your salad rather than feta.

That settles it, but just before we close, we’ll mention that they do both have great gut-healthy properties, containing healthy probiotics.

In short: if it weren’t for the difference in sodium content, this would be a narrow win for mozzarella. As it is, however, it’s a clear win.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Making Friends With Your Gut (You Can Thank Us Later)

- Is Dairy Scary? ← the answer is “it can be, but it depends on the product, and some are healthy; the key is in knowing which”

- How Too Much Salt May Lead To Organ Failure

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Is it OK to lie to someone with dementia?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There was disagreement on social media recently after a story was published about an aged care provider creating “fake-away” burgers that mimicked those from a fast-food chain, to a resident living with dementia. The man had such strict food preferences he was refusing to eat anything at meals except a burger from the franchise. This dementia symptom risks malnutrition and social isolation.

But critics of the fake burger approach labelled it trickery and deception of a vulnerable person with cognitive impairment.

Dementia is an illness that progressively robs us of memories. Although it has many forms, it is typical for short-term recall – the memory of something that happened in recent hours or days – to be lost first. As the illness progresses, people may come to increasingly “live in the past”, as distant recall gradually becomes the only memories accessible to the person. So a person in the middle or later stages of the disease may relate to the world as it once was, not how it is today.

This can make ethical care very challenging.

Pikselstock/Shutterstock Is it wrong to lie?

Ethical approaches classically hold that specific actions are moral certainties, regardless of the consequences. In line with this moral absolutism, it is always wrong to lie.

But this ethical approach would require an elderly woman with dementia who continually approaches care staff looking for their long-deceased spouse to be informed their husband has passed – the objective truth.

Distress is the likely outcome, possibly accompanied by behavioural disturbance that could endanger the person or others. The person’s memory has regressed to a point earlier in their life, when their partner was still alive. To inform such a person of the death of their spouse, however gently, is to traumatise them.

And with the memory of what they have just been told likely to quickly fade, and the questioning may resume soon after. If the truth is offered again, the cycle of re-traumatisation continues.

People with dementia may lose short term memories and rely on the past for a sense of the world. Bonsales/Shutterstock A different approach

Most laws are examples of absolutist ethics. One must obey the law at all times. Driving above the speed limit is likely to result in punishment regardless of whether one is in a hurry to pick their child up from kindergarten or not.

Pragmatic ethics rejects the notion certain acts are always morally right or wrong. Instead, acts are evaluated in terms of their “usefulness” and social benefit, humanity, compassion or intent.

The Aged Care Act is a set of laws intended to guide the actions of aged care providers. It says, for example, psychotropic drugs (medications that affect mind and mood) should be the “last resort” in managing the behaviours and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Instead, “best practice” involves preventing behaviour before it occurs. If one can reasonably foresee a caregiver action is likely to result in behavioural disturbance, it flies in the face of best practice.

What to say when you can’t avoid a lie?

What then, becomes the best response when approached by the lady looking for her husband?

Gentle inquiries may help uncover an underlying emotional need, and point caregivers in the right direction to meet that need. Perhaps she is feeling lonely or anxious and has become focused on her husband’s whereabouts? A skilled caregiver might tailor their response, connect with her, perhaps reminisce, and providing a sense of comfort in the process.

This approach aligns with Dementia Australia guidance that carers or loved ones can use four prompts in such scenarios:

- acknowledge concern (“I can tell you’d like him to be here.”)

- suggest an alternative (“He can’t visit right now.”)

- provide reassurance (“I’m here and lots of people care about you.”)

- redirect focus (“Perhaps a walk outside or a cup of tea?”)

These things may or may not work. So, in the face of repeated questions and escalating distress, a mistruth, such as “Don’t worry, he’ll be back soon,” may be the most humane response in the circumstances.

Different realities

It is often said you can never win an argument with a person living with dementia. A lot of time, different realities are being discussed.

So, providing someone who has dementia with a “pretend” burger may well satisfy their preferences, bring joy, mitigate the risk of malnutrition, improve social engagement, and prevent a behavioural disturbance without the use of medication. This seems like the correct approach in ethical terms. On occasion, the end justifies the means.

Steve Macfarlane, Head of Clinical Services, Dementia Support Australia, & Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

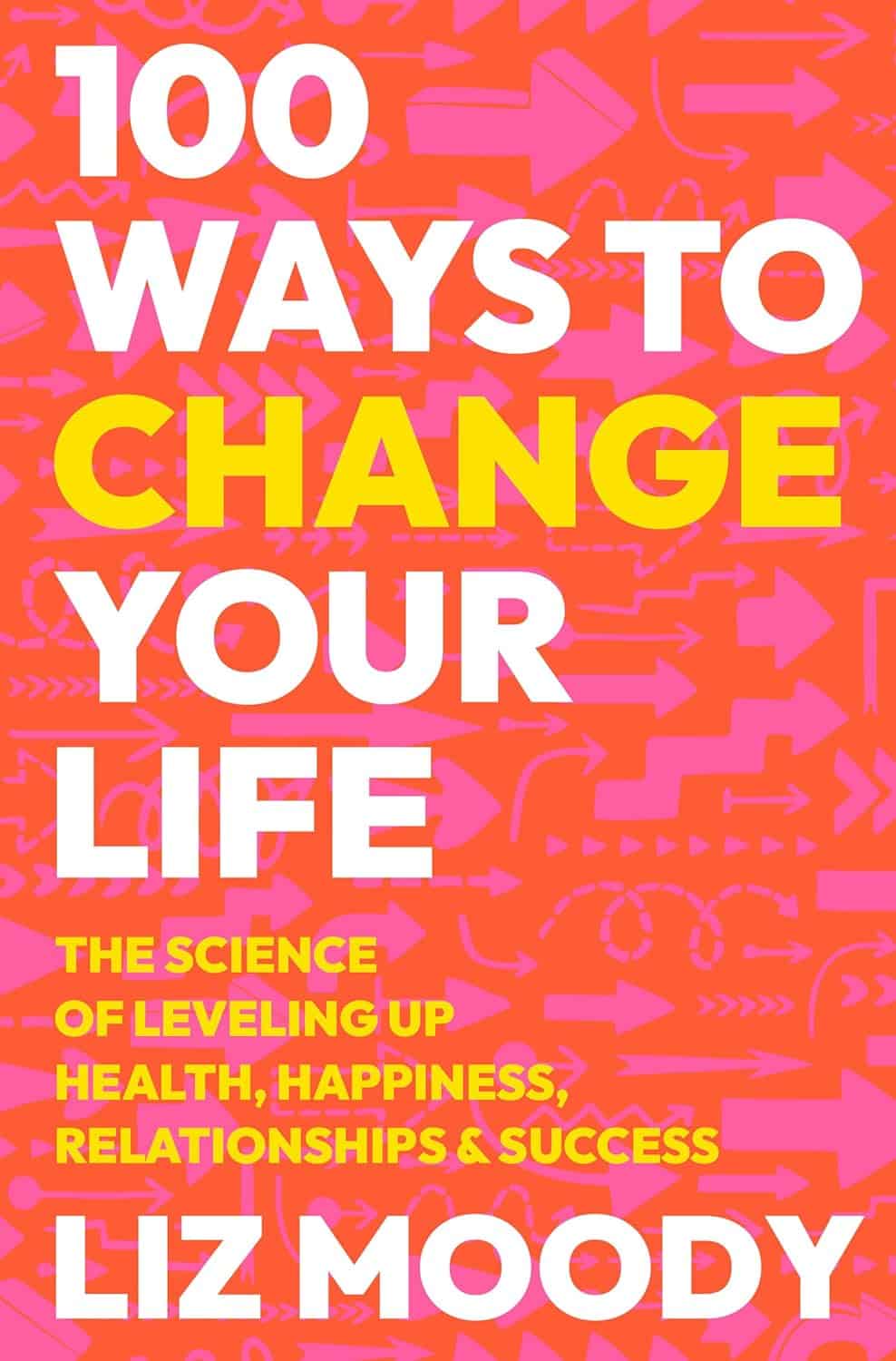

100 Ways to Change Your Life – by Liz Moody

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sometimes we crave changing things up, just to feel something new. This can result in anything from bad haircut decisions or impulsive purchases, to crashing and burning-out of a job, project, or relationship. It doesn’t have to be that way, though!

This book brings us (as the title suggest) 100 evidence-based ways of changing things up in a good way—small things that can make a big difference in many areas of life.

In terms of format, these are presented in 100 tiny chapters, each approximately 2 pages long (obviously it depends on the edition, but you get the idea). Great to read in any of at least three ways:

- Cover-to-cover

- One per day for 100 days

- Look up what you need on an ad hoc basis

Bottom line: even if you already do half of these things, the other half will each compound your health happiness one-by-one as you add them. This is a very enjoyable and practical book!

Click here to check out 100 Ways to Change Your Life, and level-up yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: